Inside RIBA's 2025 Stirling Prize shortlist: big, beautiful architecture, but rarely bold

by Bansari PaghdarSep 11, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Pooja Suresh HollannavarPublished on : Oct 09, 2023

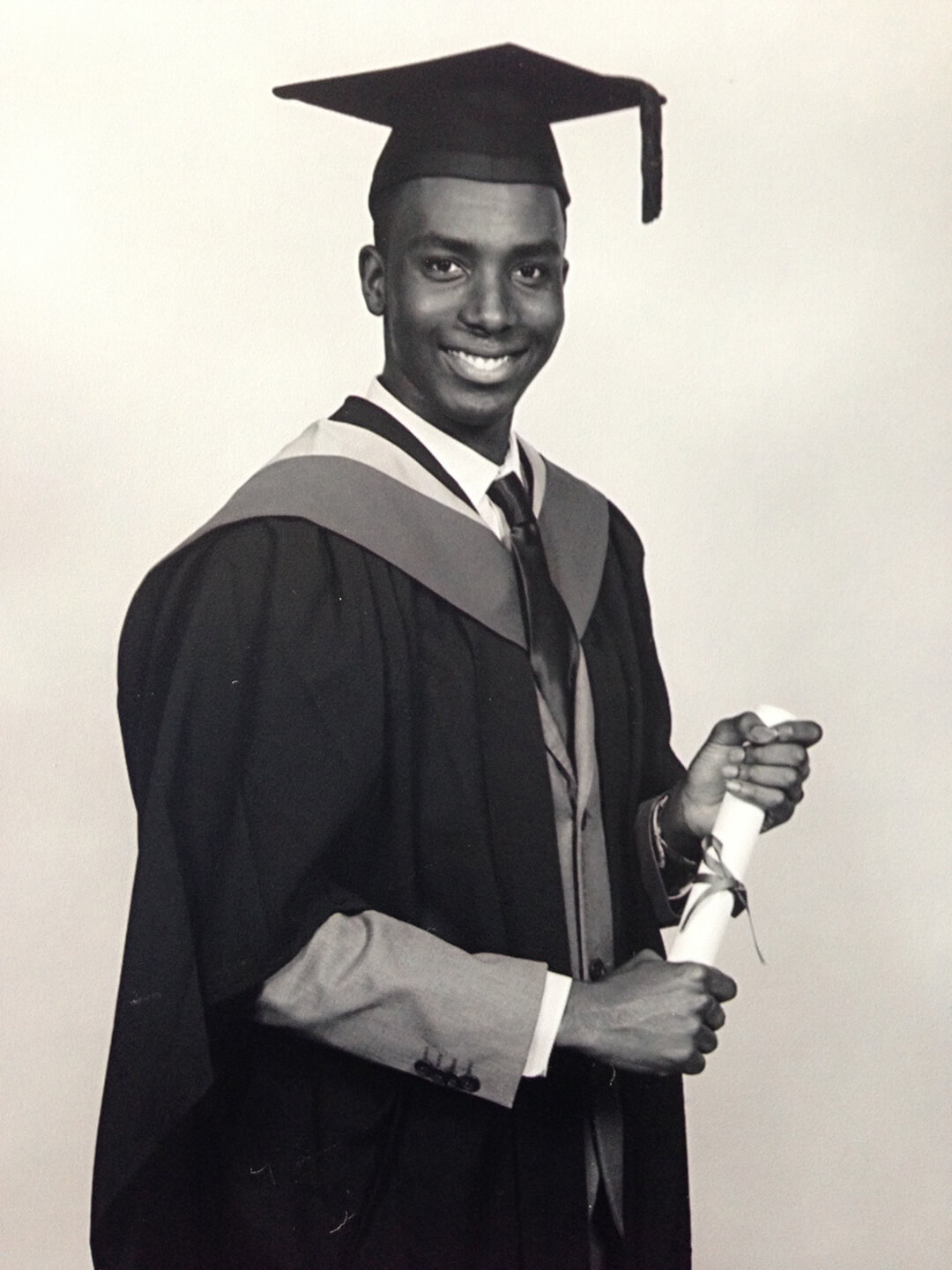

In the ever-evolving world of architecture, defined by innovation and inclusivity, the Deaf Architecture Front (DAF) is a transformative collective with a clear mission—to build bridges between deaf communities and the architectural and spatial practice industries. Founded by Chris Laing, an architectural designer with a deep-rooted passion for inclusivity and first-hand experience navigating the formidable obstacles faced by deaf individuals within the industry, the goal of DAF is to dismantle the longstanding barriers that have hindered deaf individuals from fully engaging with architectural practice. Laing has embarked on a journey to level the playing field, addressing the critical issues of accessibility and representation in the architectural world.

DAF's ambitions are two-fold. Firstly, it seeks to break down the barriers preventing deaf individuals from pursuing careers in architecture. Secondly, it strives to ensure that the unique needs and experiences of those with hearing loss are given due consideration in building design. To achieve these goals, DAF is campaigning tirelessly to expand British Sign Language resources, secure funding for interpreters, enhance work-experience opportunities, and advocate for the adoption of DeafSpace principles in architectural studios.

In an industry notorious for its inaccessibility, Laing and DAF are leading the charge for change. At a time when diversity and inclusivity are becoming increasingly paramount, Laing’s work couldn't be more timely. In a conversation with STIR, Laing talks about his reasons behind creating DAF, developing Signstrokes, and more.

Pooja Suresh Hollannavar: We read somewhere that growing up you have been very visually minded. What were some of those early days like when the world seemed like a place that existed without barriers?

Chris Laing: I was born into a hearing family, so they adjusted to my need to communicate visually by using gestures and basic British Sign Language (BSL). As a family, we created our own home signs that we could understand between us—specific, personal signs for the friends, family members, and places that defined our world. This helped me to understand and remember when I was younger. Growing up, I attended a deaf school, so on reflection, I realised that— although I faced the inevitable Dinner Table Syndrome (whereby deaf people are excluded from the family conversation)—in a sense, I lived in a bubble. As I grew older, I came to realise the difficulties of accessing the public realm, where subtitles or interpreters are rarely available, and I had to rely on family members and their limited BSL to navigate things like doctors’ appointments.

However, it wasn’t until secondary school and then university that I truly understood the extent of the language barrier that existed between me and much of the world. BSL is my first language, and every day I had to mix with hearing peers who were unable to sign.

Pooja: The first mode of communication for you was drawing. Even when you were asked to envision a house for your dad when you were eight, it was in the form of a drawing. Do you recall how that image looked? How has your relationship with drawing evolved since?

Chris: That’s a great question and something I have never thought about before. Drawing was an essential form of communication for me while I was growing up. It was especially valuable as a way for me to communicate with my stepdad. I remember that the house I drew was very out of proportion. I was drawing my dream house so of course I gave myself the biggest bedroom.

Drawing to communicate is not something I do as much anymore, probably because there is often an interpreter present. I use drawings to help me quickly solve problems—how to create strategies for my long-term DAF plans, for example. It’s much easier for me to find a solution by creating drawings to get a clear picture, compared to using written English. I find drawings less stressful than written English, too. From a young age, I have been able to express myself by drawing and this has carried through to adulthood. Drawing helps to clear my mind and express myself.

Pooja: In your practice, what is one superpower that you think you have over your hearing peers?

Chris: I am not sure I’d call it a superpower exactly, but I definitely have a visual eye for space and an acute awareness of accessibility needs. I can identify the issues of a given space quickly and confidently and can usually see straight away how the space should be adjusted to allow deaf people to communicate easily.

Pooja: What pivotal moments or realisations led you to conceptualise DAF?

Chris: My lived experience as a deaf person facing constant barriers and challenges led me to realise that the support out there for people like me was extremely limited. It had become exhausting and frustrating, and we needed a solution. I became aware of Future Architects Front—a grassroots group founded to end exploitation in the architecture industry—and saw what they were doing, and that made me see that there was a real possibility to create a campaigning platform and collective that could challenge the status quo and build a bridge between the deaf community and the architecture and spatial design industries. I want to ensure things are easier for other deaf people entering the architecture industry.

The ultimate aim is to encourage more deaf people to become architects and to provide work experience opportunities for the deaf community in the built environment sector. – Chris Laing

Pooja: Architectural education heavily relies on spoken and written language, which poses challenges for deaf individuals. How does DAF intend to address this language barrier and provide more inclusive educational opportunities for the deaf community interested in architectural practice?

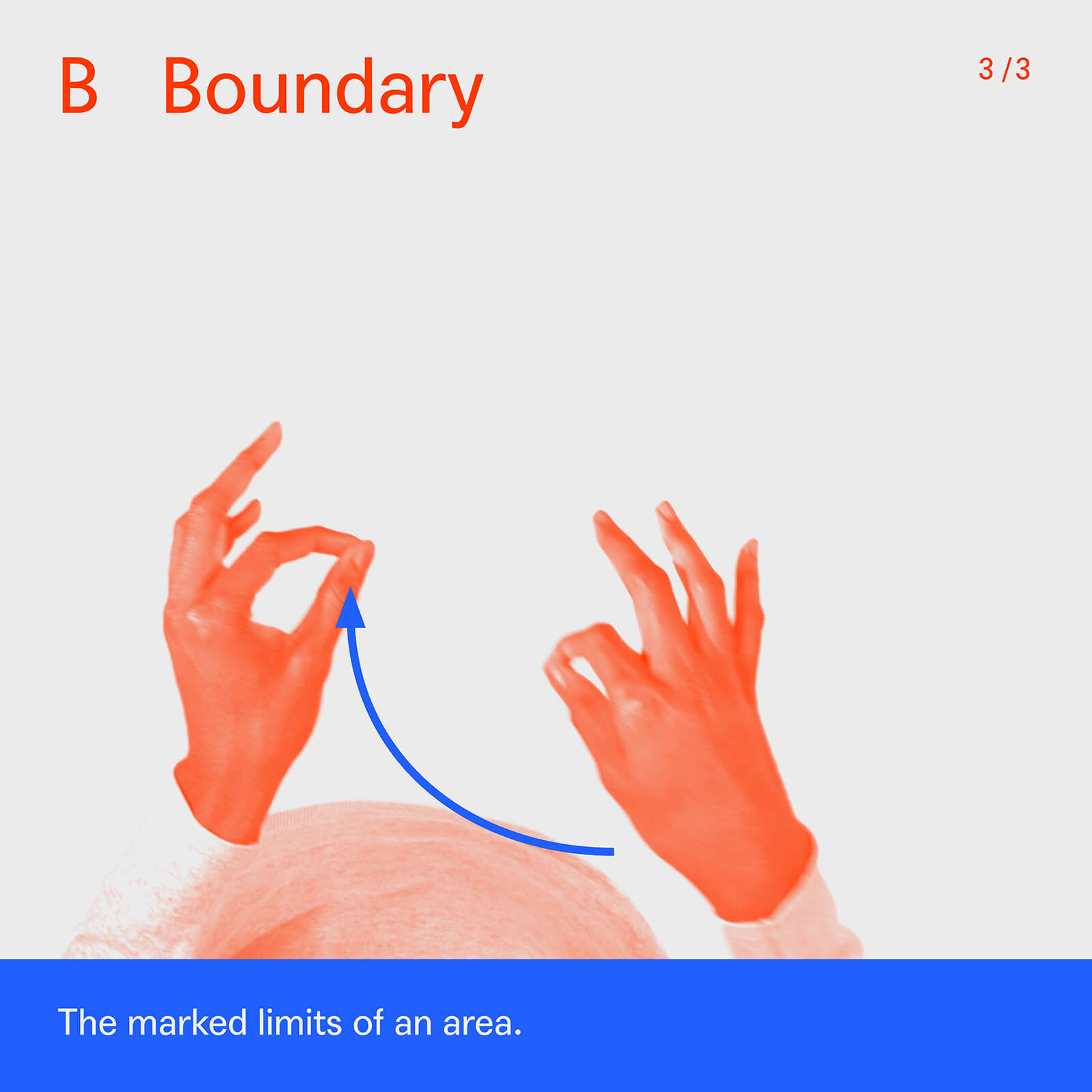

Chris: DAF plans to secure funding to continue and expand the SignStrokes linguistic project, which started in 2020. SignsStrokes is creating a British Sign Language (BSL) lexicon for architectural terminology and the built environment. Had this resource been available when I was studying, it would have made a huge difference to me and the interpreters I worked with. SignStrokes plans to expand and develop a detailed lexicon that will benefit the deaf community in education settings and general architectural practice.

Another area of work for DAF will be providing consultation services to universities and other educational institutions so that they have a better understanding of how to ensure deaf students get the most out of their education. DAF can work with university disability advisors and offer guidance on translating teaching materials into BSL. It will be a holistic approach, aiming to make deaf students’ experience of architectural education much smoother.

Pooja: DAF's focus on activism, consultation, research, and open-source resources suggest a multifaceted approach to change. What are some specific initiatives or projects that you believe will have the most impact on bridging the gap between the deaf community and the architectural industry?

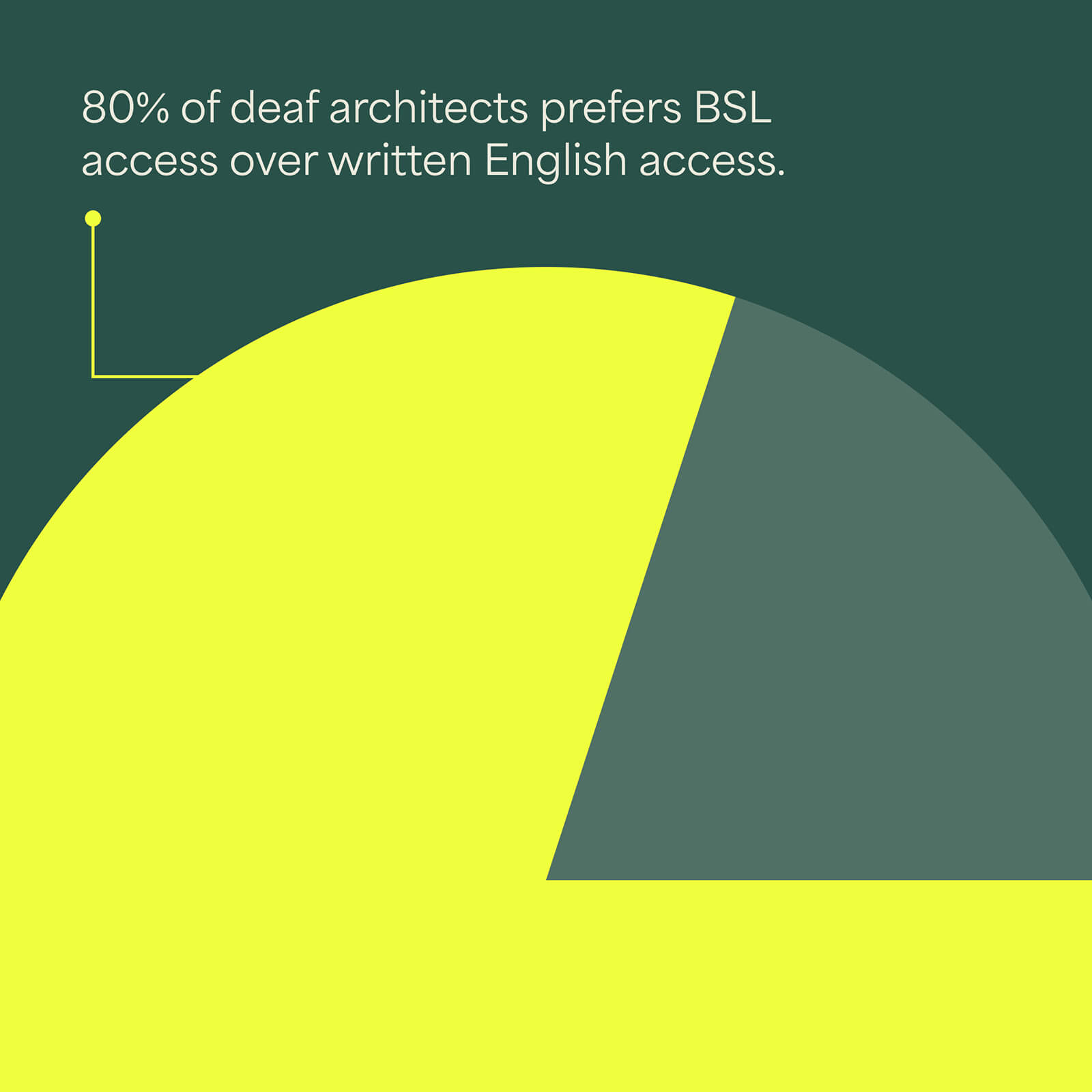

Chris: The biggest impact in bridging the gap between the deaf community and the architectural industry will be achieved through the establishment of clear guidance, accessible in BSL. I’d also like to see much greater support in booking interpreters.

One of our other principle aims is setting up a deaf network where deaf people can raise issues/concerns via a safe and supportive platform. This network could also offer an opportunity for deaf people to share tips and resources.

There are currently around five to seven fully qualified deaf architects in the United Kingdom, working full-time. If DAF sets up a consultation platform, it would give us the opportunity to give feedback on projects and offer guidance on how to sensitively adapt spaces to suit the communication needs of deaf people, rather than relying on a 'hearing loop' as a solution. Having this platform would grow opportunities for deaf people and offer a space for them to consult on projects. The ultimate aim is to encourage more deaf people to become architects and to provide work experience opportunities for the deaf community in the built-environment sector.

Pooja: Your project, Signstrokes, aims to develop a new British Sign Language lexicon for architectural terms. What were some of the challenges you faced with this project, and how did you navigate them?

Chris: SignStrokes aims to create and provide a glossary of architectural terms in BSL. The challenge it sets out to solve is the fact that, whenever I encountered an architectural term, my interpreter and I would have to come up with a sign to use at that moment—but it would only ever be temporary because a different interpreter would be working with me the next day, and the agreed sign would not be understood by anyone else.

I want Signstrokes to be a resource where the terms can be agreed upon and shared online. This eliminates the need to explain to individual interpreters afresh each time and minimises fingerspelling. It frees up head space to focus on work and be on an equal footing with hearing people rather than trying to establish signs on the hoof during meetings, pulling focus from the task at hand.

My vision for the future is that DAF will break down the barriers for deaf people, and really open up the world of architecture for my community. – Chris Laing

Pooja: Public consultations are a vital aspect of architectural projects, but accessibility remains a challenge for the deaf community. Does DAF have any strategies for providing BSL translations of written English and ensuring interpreter availability during these consultation events to promote deaf inclusion?

Chris: DAF aims to offer online opportunities to access public consultations in a way that suits individual needs—for example, some deaf people may not feel comfortable attending face-to-face meetings and would rather set up private group consultations and feedback collectively. They can also suggest preferred interpreters who are aware of architectural jargon and that they would prefer to work with.

Online, there could also be an option to have information all on the same page, in BSL, with links to SignVideo and SignStrokes as a resource. This would enable deaf people to be included in the consultation process and to feel empowered to feedback using a communication method they feel comfortable with.

Pooja: What is your vision for the future impact of the Deaf Architecture Front?

Chris: My vision for the future is that DAF will break down the barriers for deaf people, and really open up the world of architecture for my community. The DAF platform will be a resource where deaf people can access information in their first language, and I hope this will encourage more deaf people to study and work in the field of architecture. There are so many opportunities for our consultancy work, improving accessibility and providing advice and much-needed resources. The benefits DAF can bring are immense.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Pooja Suresh Hollannavar | Published on : Oct 09, 2023

What do you think?