Outlooker Design converts an ancient Hui-style home into a restaurant and café

by Jerry ElengicalDec 03, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Jerry ElengicalPublished on : Jun 20, 2024

In a setting famed for its resemblance to the sublime scenery portrayed in landscape paintings, a pair of traditional Chinese homes form the basis of an adaptive reuse project by Shanghai-based Domain Architects, dubbed the Lakeside Teahouse. Dating back to the 1930s, the two dwellings are located along the southern shore of Nanbei Lake, a serene tourist spot in Zhejiang Province of China.

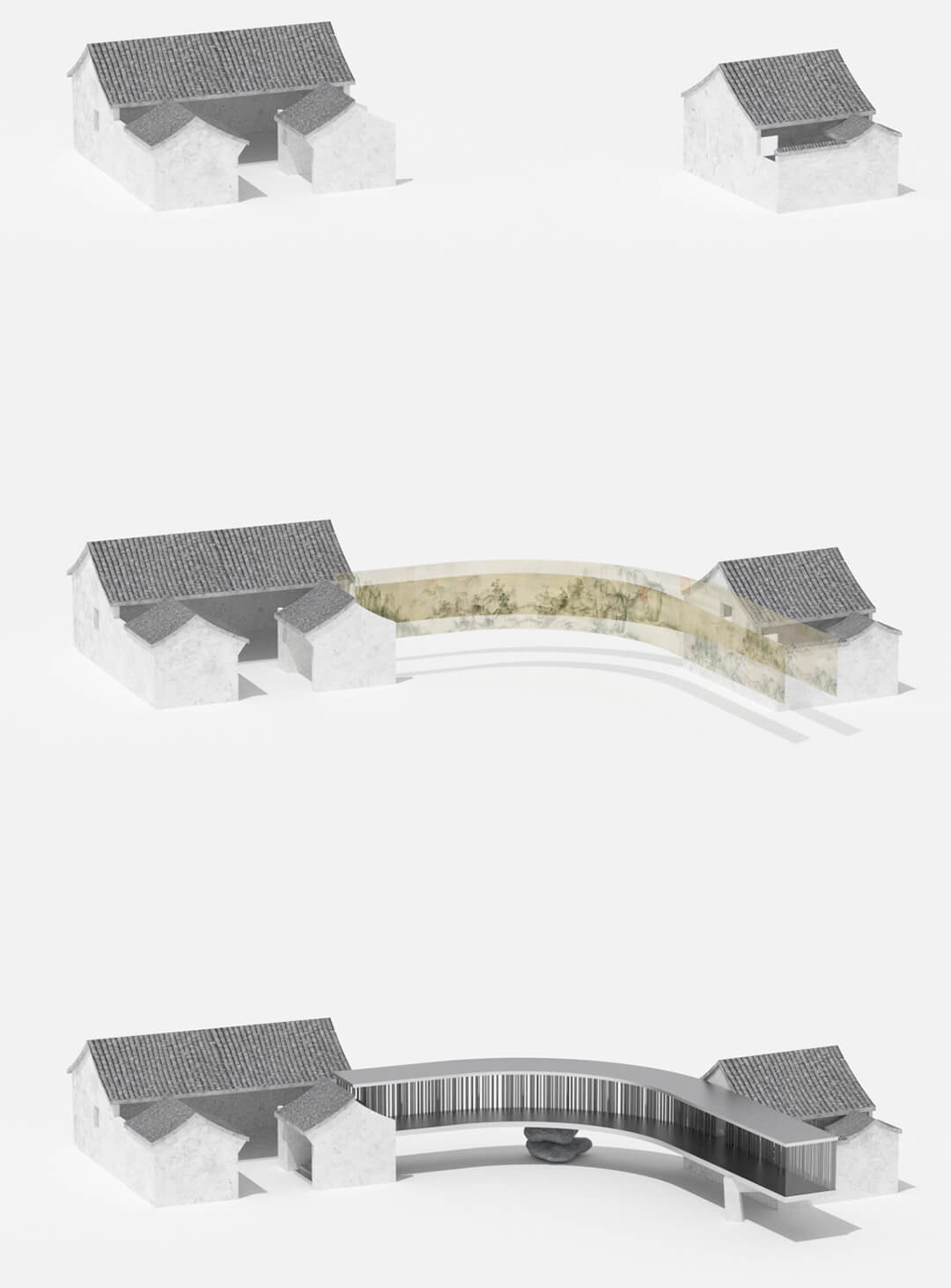

Within this context, the smaller house among the pair is situated to the north of its larger counterpart. Conceived as a tearoom and rest stop, the project’s purview concerned the restoration and integration of both houses with the addition of a direct link for users to move between them.

Over the past few years, adaptive reuse and restoration have gained considerable traction across various spheres of contemporary architectural practice, even though these methods of breathing new life into old buildings existed long before they became as fashionable as they are now. Some of the driving factors behind this recent shift range from concerns over the preservation of architectural heritage and elements of regional cultural identities, to how this approach diminishes the carbon footprints of projects when substituted in place of demolition and new construction. Both these perspectives came into play during the design of Lakeside Teahouse, as a consequence of its scale, typology, and site.

While approaching this project, the team at Domain Architects took great care to retain the original character of both buildings, ensuring they still maintained a connection to the spirit of their context. For the most part, the timber framing in the houses was left untouched, with some minor exceptions where the original structure had deteriorated. Possessing modest façade designs, the pair of homes feature gabled roofs and unembellished entrances, employing a neutral, earthy material palette of wood, stone, and tile.

In conversation with STIR, Xu Xiaomeng, founder of Domain Architects, explains, “We almost instinctively hoped to preserve the old houses as much as possible. Part of the roof of the bigger house had collapsed, so we decided not to rebuild it, but let the new structure start from the collapsed part. This allowed us to leave the other house intact, and have the new structure just run next to it.” He adds, “A few wooden columns and beams were replaced for safety reasons. Some tiles were also broken. They were substituted with the same kind of old tiles collected from a nearby village."

Typologically, the revamp of the residential designs of both homes, was aided by the presence of skywell-style courtyards within their plans as per Xu Xiaomeng. He states, “A common feature of traditional Chinese architecture is that the forms are very generic as opposed to serving a specific function. So the two courtyards attract more attention than the functionality of both homes as examples of residential architecture. We decided to enhance the experience of the two courtyards through a juxtaposition of new and old elements, which makes the old houses stand out when viewed from a distance. This sharp contrast also pushes people to notice the older details of both structures.”

At a fundamental level, the intervention’s most salient feature is perhaps the raised bridge, which spans between the houses along the curve of an arc. The terrain beneath it had been eroded by the action of a seasonal creek, and the designers took advantage of this to create a pond. Much like the aesthetic tendencies observed in landscape paintings created by Chinese literati in the past, the bridge is the focal point of the entire composition. Such paintings were also generally rendered on long hand scrolls, which allowed viewers to gradually take in the intricacies of the artwork as they unfurled them. Domain Architects honed in on this concept and applied it to their bridge design.

From the ground level, the bridge can be accessed through an entry gate adjacent to the larger house, with a set of steps leading upwards. Moving through the shaded corridor above the pond, visitors can see shifting views of the lake through the clear glass panels covering its front-facing side. Conversely, the other side of the bridge is shrouded in an array of polycarbonate tubes and steel posts, which filter sunlight, facilitate natural ventilation and produce rippling shadows along the floor.

Xu Xiaomeng elaborates, “We took two types of radically different approaches. In terms of the material and tectonic language, we did not want to merge traditional and contemporary, but to create a vivid contrast on site. In terms of the experience, it is an abstraction of the corridors and bridges in Chinese landscape paintings. Walking within the bridge is reminiscent of the act of unfolding a hand-scroll.”

At the other end of the bridge, the structure opens into the smaller house through its rear wall, before extending further beyond the pond to cantilever towards the direction of the lake. Although it connects both houses directly, the transition from the bridge to either house is not seamless, with the gaps between them highlighting their identities as separate, linked entities. Moreover, the bridge’s configuration as a single-sided cantilever posed a challenge when the designers had to manage the deformation of the structure to achieve stability. However, they managed to find an apt solution to this.

Viewed from the outside, the bridge is perched atop three distinct structural supports, which hide in plain sight and reference the miniature man-made landscapes seen in Chinese garden design. On its cantilevered side towards the lake, the bridge rests on concrete support shaped like the number ‘7,’ whereas the midpoint of its span over the pond is held up by a piece of natural stone, functioning as both structural member and landscape design element. Finally, the other end of the bridge is affixed to one of the gable-roofed structures projecting from the larger house.

In the words of Xu Xiaomeng “The three supports were designed in three distinct ways, to emphasise the design’s levity and intimacy. Although the structural consultants had already ascertained the bridge’s stability, the contractor wanted to add a concrete column. It took some effort to persuade the client and contractor that it was redundant and needed to be removed. Naturally, in some situations, it is not always easy to convince collaborators that something can be built as designed.”

From the entrance to the compound to the cantilevered end of the bridge, the experience of moving through the project’s functional areas features spatial expansions and contractions that are similar to the inherent rhythms of classical Chinese gardens. In its completed form, the project now casts an otherworldly aura over a pair of structures whose earlier mundanity had led them to fall into disrepair. Offering a serene viewpoint towards the lake, which exudes an almost ritualistic ambience, Lakeside Teahouse cements the idea that adaptive reuse can safeguard architectural heritage at any scale, transforming the ruins of yesteryear into the landmarks of the present day.

Name: Lakeside Teahouse

Location: Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, China

Year of Completion: 2023

Built Up Area: 245 sqm

Client: Haiyan Nanbeihu Scenic Zone Investment Development Co., Ltd.

Architect: Domain Architects

Lead Architect: Xu Xiaomeng

Design Team: Xu Xiaomeng, Hannah Wang

Structural Design: AND Office

Contractor: Zhejiang Lixin Construction Group Co., Ltd.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Jerry Elengical | Published on : Jun 20, 2024

What do you think?