'In Between the Notes' at Experimenter presents a rich body of sound art

by Manu SharmaOct 14, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Mar 13, 2024

How does language shape creative practice? Performing in Mumbai in January 2024, the British musician and composer Soumik Datta shares an intriguing set of words with his audience. There are ripples of laughter as the audience makes its way through the list—gadha (donkey), chagol (goat). His teacher, the sarod maestro Buddhadev Das Gupta, often used these vivid terms to express dissatisfaction in the classroom or convey his feedback. A fond irony filling his voice, Datta recalls his teacher’s deeply specific vocabulary—abar (once more), baarbar (again and again) and bajao (play)—both teacher and student mapping their journey on the sarod through shared reference points in language. These memories underpin Datta’s new performance work, Mone Rekho (‘Remember’ in Bengali), an immersive concert which had a run of shows at the performance venue G5A in Mumbai in January 2024. Mone Rekho is produced by Soumik Datta Arts in partnership with Bagri Foundation, University College of London, Hawkwood Centre for Future Thinking, PRS Foundation, Dartington Trust, Arts Council England, G5A Forum, BNP Paribas and the Southbank Centre.

A winner of the 2022 Aga Khan Music Awards, Datta has a longstanding practice, including collaborations with musicians Anoushka Shankar, Talvin Singh and even Beyonce. Mone Rekho draws on memory, forgetting and misremembering in two contexts. Datta delves into his memories of time spent training with Das Gupta in Kolkata. He also draws on conversations with elderly care home residents in the UK, from his time working with Dr Naaheed Mukadam, an Alzheimer’s Society Senior Research Fellow and old age psychiatrist, on a research project that explored memory and identity through music and dance. "There are these strange correlations between how memory and music work and the fact that music requires so much memory to play it anyway," Datta says in an interview with STIR. He also draws from neurologist Adam Zeman’s research, particularly his book A Portrait of the Brain (2008). Zeman’s work helped Datta process ideas of repetition and erasure and consider how they lent themselves to slow transformations in Indian music. "The brain is a time machine. And if it starts to slip, you don't really know if you're in a fantasy that never happened or if you're in the past, in a real memory,” Datta muses.

An intergenerational reckoning of lineage is crucial to how artists locate themselves in Indian classical music. Through Das Gupta, Datta traces his musical lineage five generations back to the 19th century musician Murad Ali Khan. Indian classical music is primarily an oral tradition, where students learn through virtuosic repetition until the music becomes part of their muscle memory. Datta was curious to find a different route into his highly structured training; what would happen if he forgot his guru, he wondered? What would happen if he forgot to play? When he tried to combine the patterns he remembered in unlikely ways or play them ‘wrong’, there was new music to be made, he discovered. “Each piece that I play has to do with either a beat getting lost or a memory (of his time with Das Gupta) getting lost. Or misremembering one composition with another one and fusing the two. Or playing in one raga and then suddenly discovering that you are in a different raga," Datta says about arriving at the gradual shifts between rhythms, musical patterns, stories and ideas in Mone Rekho.

Datta works with several collaborators in Mone Rekho, including dramaturg Zoë Svendsen, surround sound engineer Camilo Tirado and visual designer Simon Daw. Tirado’s surround sound helps Datta create soundscapes that are rooted in his memories. At one point in the show, he recreates the sounds he remembers from an early morning journey from his Kolkata home to his teacher’s house—morning rituals, temple bells and vehicles on the road, giving way to streets that gradually awaken to a new day over the course of his journey. Working with Svendsen helped Datta explore his relationship to storytelling; Indian classical musicians often break the fourth wall to chat with the audience, narrating personal anecdotes or dwelling on the intricacies of a musical composition. Datta moves between spoken anecdotes and musical compositions, working with a tabla player, in Mumbai, he performed with local percussionist Ishaan Ghosh.

In Hindustani music, each raga is assigned a prahar or time of day. The prahar sets up an atmospheric framework for the raga. What would it mean to equate the prahar to a time zone? Datta cites British artist David Hockney as an inspiration in his use of time as a canvas. Hockney makes photographic collages he calls ‘joiners’, composite images pieced together from individual photographs. “You can’t have a piece of music without time,” Datta reiterates. He improvises with temporal concepts like prahars, considering how he might weave experiences across narrative and musical time.

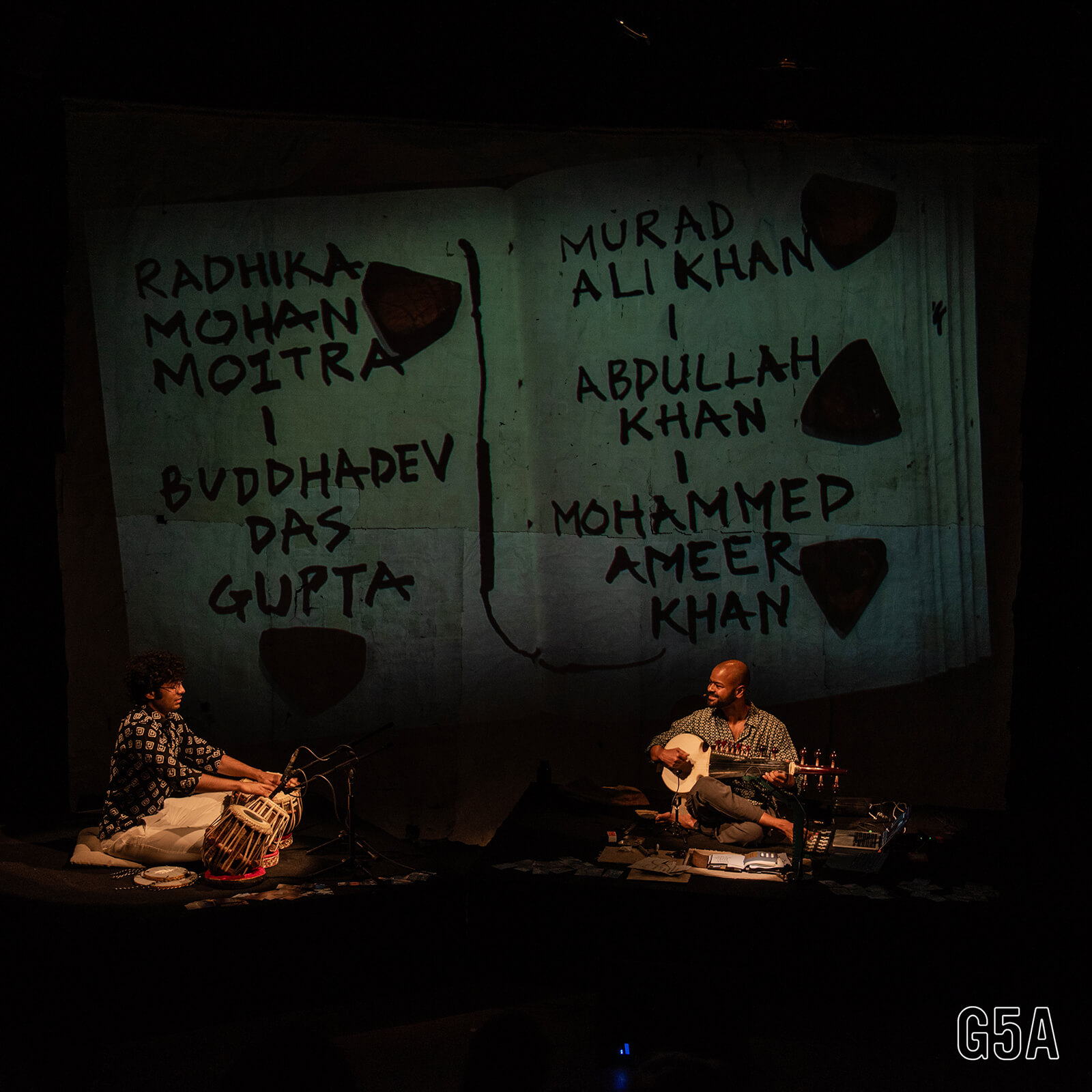

Learning and making music is tumultuous. Musicians learn to inscribe melodies and rhythms into the body—arriving at their precise locations in space and time through a slow process of accumulation and several mistakes. To reflect this chaos, the stage in Mone Rekho is deliberately a mess, dotted with the tools of Datta’s trade—loose wires, a laptop and pages from his journals. As the show travels, Datta also works with local paper makers on elements of Mone Rekho’s set design, including a 'music book' that becomes the bridge between memory and identity, where the intimate minutiae of his relationship with his teacher comes to the fore—in gruff fragments of feedback, stray rhythmic patterns and a simple tracing of his lineage. The coconut-shell plectrums Datta collected over years of playing the sarod become a recurring motif–arranged and rearranged to emphasise words and patterns on the page. Mone rekho, remember, Datta’s teacher would instruct him. In Datta’s performance, the term mone rekho is a call to action, simultaneously rooted in the past and the future, in memory and imagination.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Mar 13, 2024

What do you think?