Art Jameel and theOtherDada imagine innovative interspecies structures into being

by Niyati DaveApr 05, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Aarthi MohanPublished on : Mar 19, 2024

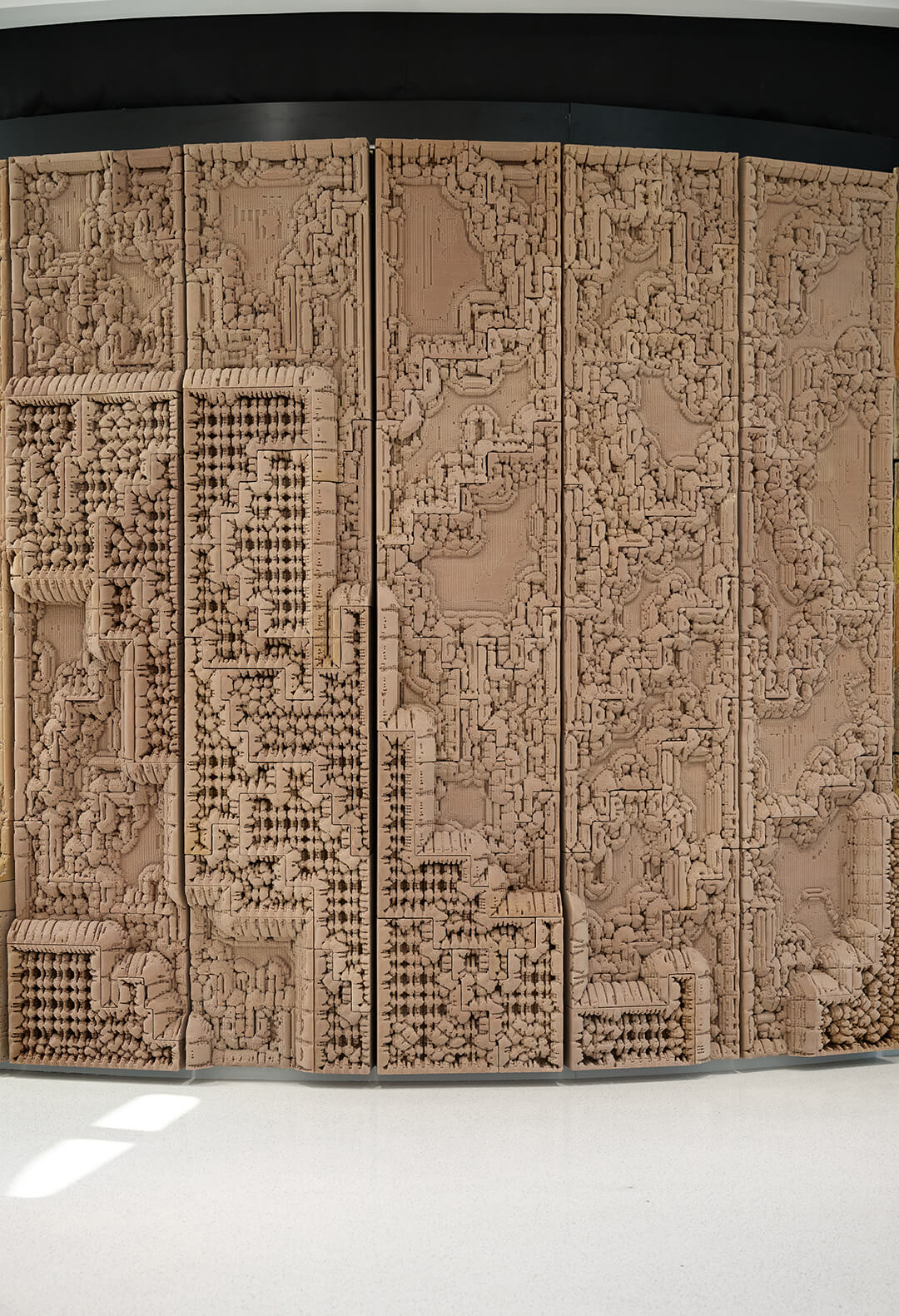

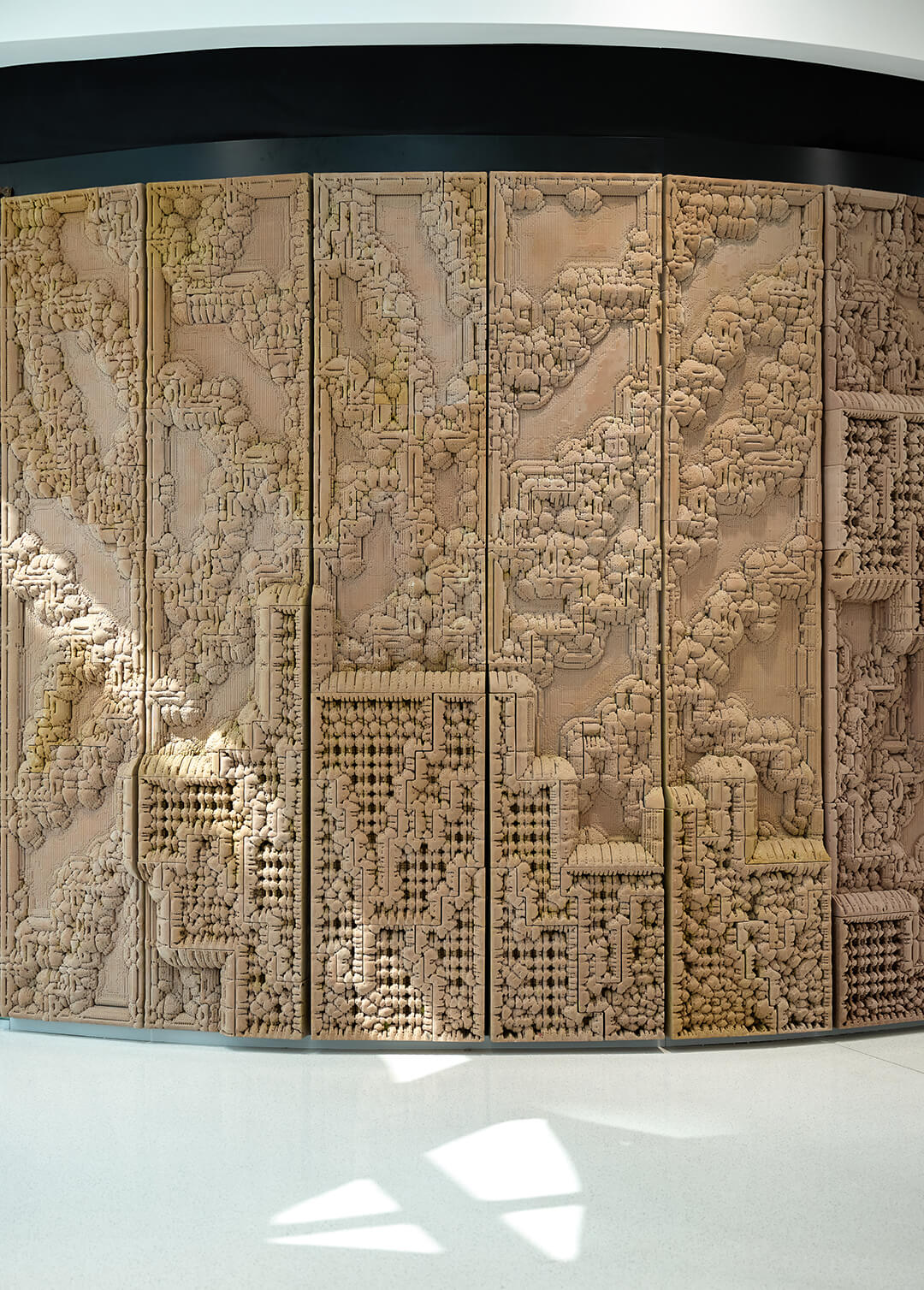

Imagine a world where architecture blurs the lines between the natural and the artificial, inviting us to reconsider our relationship with the environment. This is precisely what London-based architect and designer Barry Wark’s 3D installation, Nadarra, seeks to accomplish. Through its innovative approach to 3D printing, the installation, which is now part of the Dubai Museum of the Future’s permanent collection explores new and formal aesthetic conditions that respond to the challenges of the Anthropocene. Wark’s project challenges conventional notions of architecture by highlighting the fluidity and ambiguity inherent in the relationship between the organic and the constructed.

Reflecting on his inspiration, the designer shares, “My work is known for its novel ideas on the intersection of ecological design, theory and application through advanced digital design and fabrication tools.” Embracing the philosophy of Ecocentrism, the large-scale installation delves into the deep qualities of the earthen, the lithic and the intricate. Through meticulous attention to detail and a keen understanding of ecological processes, Wark seeks to undermine the profession's traditional focus on vegetation, shining a spotlight on the diverse actors that compromise our global environment. Moreover, Nadarra’s use of 3D-printed sand reflects its commitment to sustainability and circularity. He elaborates, “By utilising recycled sand that can be ground down and recycled up to eight times, the installation embodies a circular approach to construction, sustainable design minimising waste and environmental impact.”

Looking to the future Wark envisions the transformative potential of 3D printing technology in construction. He shares, “Although the technology has been around for many years, sand printing is only beginning to find its application in spatial design and architecture. In time, I envision we can create interiors, facades and even structural elements with this technology, ushering in more ecological building practice." With binder jet printing offering newfound possibilities for utilising local materials, Nadarra points towards a more sustainable future for architecture in the UAE and beyond. In an exclusive interview with STIR, Wark shares insights into the conceptual underpinnings of the wall and its profound implications for the future of architecture.

Aarthi Mohan: How do you believe this aesthetic accurately reflects our contemporary understanding of the environment and ecology?

Barry Wark: In many other design projects, the environment is typically expressed in a symbolic way where vegetation (symbolising nature) is applied to a surface (symbolising artefact/man) based on the notion of two separate entities being brought together. Instead, my work explores a sensibility that all objects, both living and inert, are interconnected and less easily defined as natural or artifactual. Nadarra embodies this contemporary understanding of matter; it is ambiguous, oscillating between registers of both the natural and the artificial in its formal and aesthetic qualities, giving a sense of both simultaneously.

Aarthi: How do you think spatial experience and affect play a role in achieving human imagination to consider wider notions of ecology and interconnectedness of matter?

Barry: Ecology and the idea of the 'interconnectedness of all matter on the planet' exist on such a large scale in time and space relative to us that it is almost impossible for us to perceive or think about in its entirety; this is what philosopher Timothy Morton refers to as Hyperobjects. Through spatial design, architecture can take these gargantuan ideas and make them more relatable to us on the human scale. When buildings pique our curiosity and engage us through our senses, they can provoke thoughts and stimulate our imagination. I don’t find it unreasonable to say that what we think and experience can affect us. So, if we want to engage urban inhabitants to think about a world beyond what they can directly perceive, architecture has the potential to do so through its aesthetic qualities.

Aarthi: Could you discuss the importance of highlighting other climatic and nonhuman actors in the environment within your work?

Barry: Flora, fauna and weather are always present in our built environment but we have actively removed their visibility through construction details, material applications and building maintenance. If we are to promote ideas of interconnectedness, then displaying these other actors that constitute our environments is an important endeavour. In my work, I attempt to design buildings to purposefully display their existence through positive weathering effects and non-determinate plant growth.

Aarthi: Could you discuss how you utilised ambiguity in form, texture and materials in Nadarra to challenge the dichotomies of artefact and “nature”?

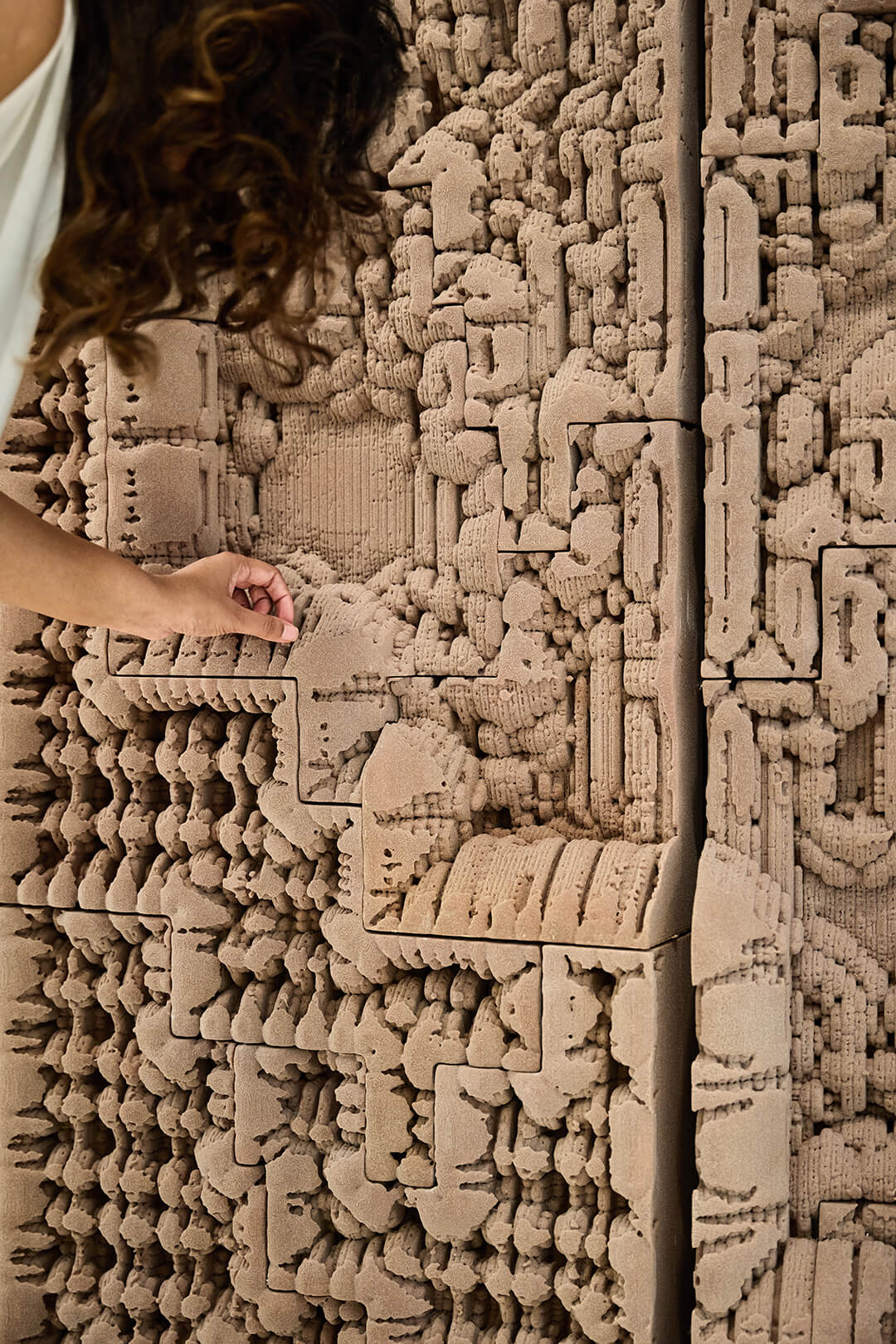

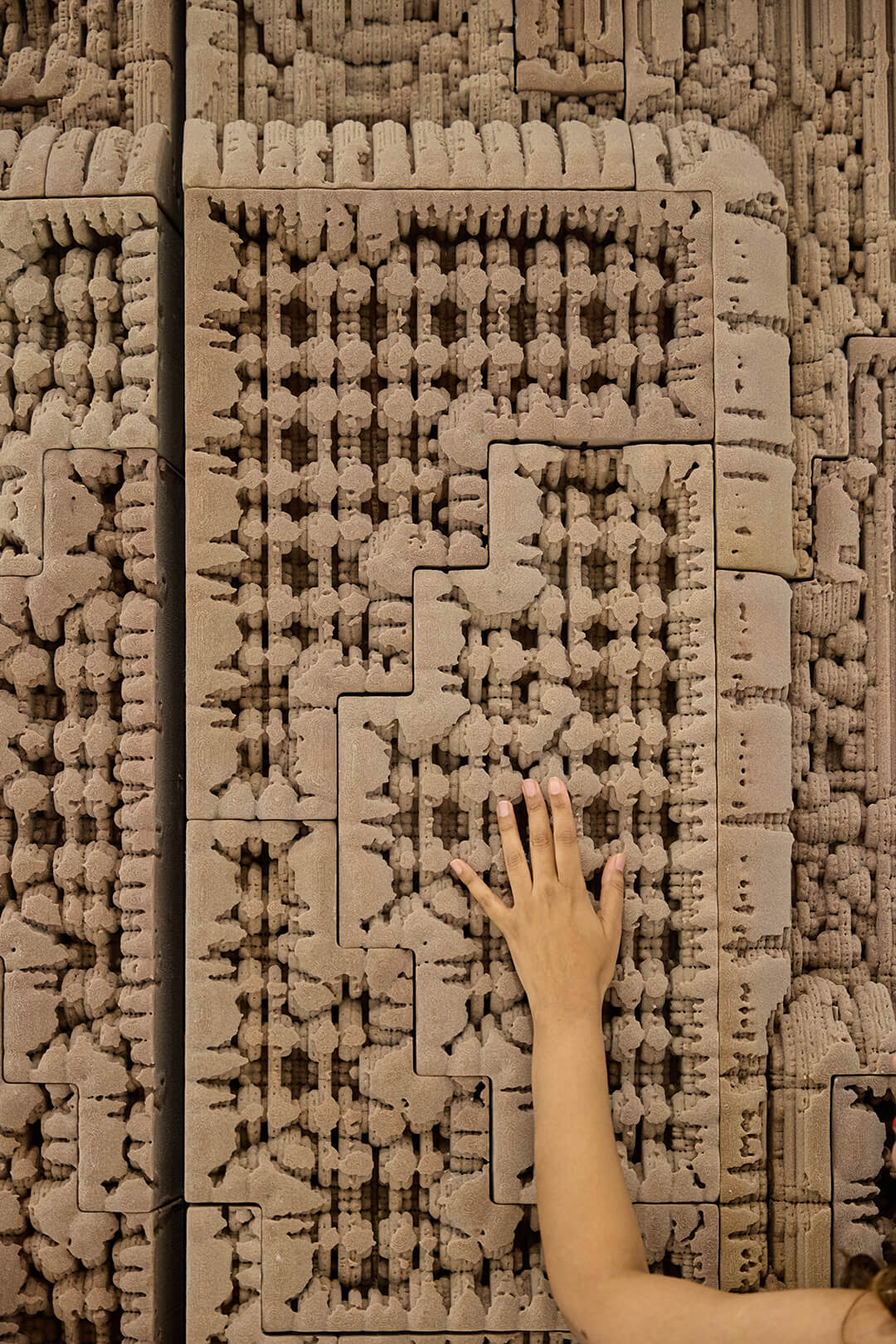

Barry: We can tend towards reductionist labels to simplify the complexities of our world. My work engages people to question these labels by asking what is before them. The nature-artefact dichotomy broadly defines how we separate ourselves and our objects from other things. By highlighting that this separation might not be easily defined, we and, by extension, our artefacts might not be as easily separated either. Nadarra explores this ambition through its aesthetics and associated qualities. It has traces of the linear quarrying techniques for cutting stone, suggesting it was taken from the earth; it also has digital traces of the horizontal contour as it expresses its printing layers. It has qualities of bulbousness and what might be described as a form akin to natural growth that is not found in machined objects; it is heterogeneous but the same, a quality found in natural systems. These qualities work together, sometimes congruently and sometimes in contradiction, resulting in an ambiguous object.

Aarthi: Considering the use of local materials in Nadarra and its potential ecological implications, how do you see this impacting the future of building practices, especially in regions like the UAE?

Barry: Architecture should engage with the biomes they are in, asking about how the buildings designed there might become materially and environmentally specific. Working with local materials found in the Middle East is extremely important in reducing the environmental impact of global supply chains, which can require a tremendous amount of energy to move around. Every biome has its vernacular, which is a great place to start.

Aarthi: What potential do you see for 3D printing technology in reshaping the future of construction and architectural design?

Barry: 3D printing has the potential to be both beautiful and practical. If the machine does not care if it creates a cube or intricate form, it opens significant territory for architecture to rediscover some of its lost qualities. Through the modernist project, architecture became very mean in using standardised sheet materials. The flatness and lack of detail equate to some form of sensory deprivation. In contrast to the dull and repetitive curtain-wall facade or the white plasterboard interiors that characterise most of what we build today, we have spent most of our existence as humans in visually rich and stimulating natural environments. If we draw from environmental psychology and biophilic theory, humans still resonate with spaces with the same visual qualities as the natural world.

This includes moments of organised complexity and a fractal-like quality of increasing levels of intricacy in areas where humans get close to the structure. Both of which were abundant in pre-modernist architecture. This is possible again through creating bespoke elements that are not standardised outputs from production lines. Secondly, nearly all regions can obtain granular materials, so most can employ 3D printing technology. In that way, it could become a universal manufacturing technique. 3D Printing can also be done on-site or on prefabricated architecture, which can make it flexible in terms of the needs of the construction of the building.

Aarthi: Can you explain the rationale behind utilising 'jigsaw' panels in Nadarra's construction and how it contributes to the project's overall sustainability and efficiency goals?

Barry: The shape of the blocks has two primary functions in the project. First, they create stability in the assembly. Like the ruins of Sacsayhuaman in Cusco, Peru, the block's form allows them to withstand seismic movement. It speculates that if the wall became free-standing, it would obtain stability by thickening the parts slightly. The second function of the ‘jigsaw’ is that a part can only be placed in its exact, intended location. In contrast to a jigsaw, however, it is not meant to be challenging to build or a puzzle to solve; it is the opposite. All parts are labelled in numerical order, which means the whole structure can be constructed in 45 minutes by easily slotting the parts into one another.

Aarthi: Could you detail the circular materials approach employed in your project, particularly regarding the use of 3D-printed sand that can be ground down and recycled multiple times?

Barry: When we consider circularity, the first principle that comes to mind is that elements will be reused as they are, such as reclaimed bricks. Still, no construction element can last forever and will eventually fail. The second principle is that the elements can go into landfills if they don’t become toxic or pollutants and we can extract more, for example timber. Putting elements in landfills is a waste of the energy that was used to extract those materials in the first place. One potential strategy is to develop a system that recycles matter within a closed system. This has the potential to become a much more ecologically driven project, especially when the recycling and remanufacturing of the matter into construction elements can happen near the cities where they are being installed and used. Nadarra is a speculation on how sand can be used in this regard. Still, many other materials could be reconstituted to a granular form and then printed, so long as ample time and research are given to their properties and integrated with environmentally considered binding methods to solidify them.

Aarthi: Can you elaborate on the qualities of the earthen, lithic and intricate that Nadarra explores?

Barry: There is a tendency to define and associate images of environmental architecture with vegetation, so much so that it is often referred to as ‘green’ architecture. This is problematic as not all cities exist in these kinds of biomes. Attempting to recreate highly vegetated environments in regions that do not have the climate to sustain them passively is environmentally costly in terms of the water and energy required. In contrast to this paradigm, my sensibility for ecological architecture is derived from matter forming and reforming over large timeframes. The resulting qualities are more akin to the ground than to vegetation, a ground that is manipulated and extracted, returning to the earth in time. For me, it is upon manipulated ground as an assembled structure that biological actors, such as vegetation, mosses, lichen, etc., can take hold. So, my work is more inspired by ruins, grottos and ancient architecture composed of earthen and lithic materials rather than biology or vegetation. The intricacy of the work is part of a broader conversation about sustainable architecture and its aesthetics. It is a tool to create a built environment that can engage people through spatial experience and affect. In my work, all these properties combine to explore how our contemporary understanding of the environment might manifest through architecture in the age of ecological awareness.

As we reflect on Wark’s Nadarra, we are invited into a world where architecture becomes a dialogue between the organic and the constructed. Through his innovative approach, the designer challenges us to rethink traditional notions of space and materiality, offering a glimpse into a future where ecological design and technology coalesce seamlessly.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Aarthi Mohan | Published on : Mar 19, 2024

What do you think?