Hope with every brick: Zimbabwe's Rising Star School overcomes resource scarcity

by Akash SinghNov 15, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dhwani ShanghviPublished on : Dec 09, 2024

When Mughal emperor Akbar ceded Palanpur (formerly Prahladan) to the Nawab of the Kingdom of Jhalore in Rajasthan, India, it marked the beginning of 330 years of the Jhalori Nawabs’ rule. With them came nobles, farmers, traders and administrators—many of the latter being Kshatriya Rajputs who had embraced Jainism under the guidance of Jain munis. Known as the Palanpuri Jains, they are known for their strong familial and inclusive community bonds, which have been instrumental in their remarkable success in the diamond trade.

While many families have since moved to larger cities, the Palanpuri Jains still maintain strong ties to their roots in Palanpur, Gujarat. Philanthropic efforts, such as those by the Vidyamandir Trust, continue to benefit the city’s residents, offering quality education and inclusive work opportunities for differently-abled individuals.

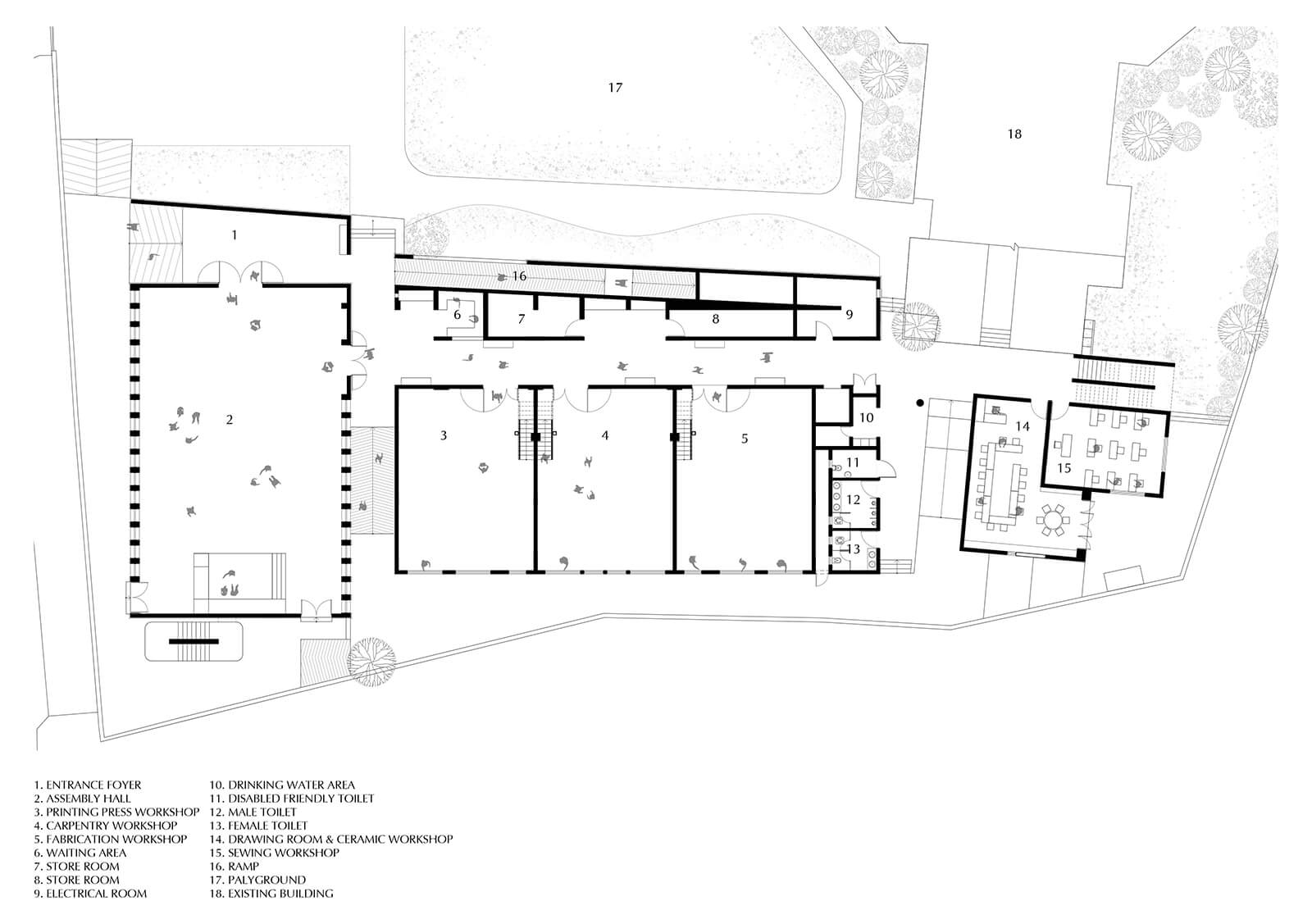

Sahyog (translating to cooperation, help or collaboration), a development space for persons with disabilities, is a school for the differently-abled on the campus of the original Sahyog established in the 1960s. Today, along with workshops and a school offering a Master in Education for Special Education, it serves as a 'living laboratory' where teachers refine skills through hands-on engagement with students of diverse abilities. Architect Nishant Mehta of Mumbai-based Studio NM has a long-standing association with the town as well as the trust and embodies the values imbibed by the Palanpuri community in the design of the school campus' extension - uplifting in its vision and inclusive approach.

In an interview with STIR, the Indian architect revisits the process of designing an educational architecture dedicated to students with diverse disabilities (spanning visual, auditory and cognitive challenges), and what went into conceiving a human-centric, climate-responsive, intuitive architecture rooted in his ancestral town.

Dhwani Shanghvi: Could you share some childhood memories of staying in Palanpur and how that shaped your connection to this project?

Nishant Mehta: The school design for the differently-abled in Palanpur becomes more than just a functional project—it's an opportunity to bridge the past and present, to bring together personal heritage and professional expertise. My unique perspective as someone who comes from a family deeply rooted in the diamond jewellery business, while having trained in architecture, gives me a distinctive lens to view my hometown and its architectural fabric.

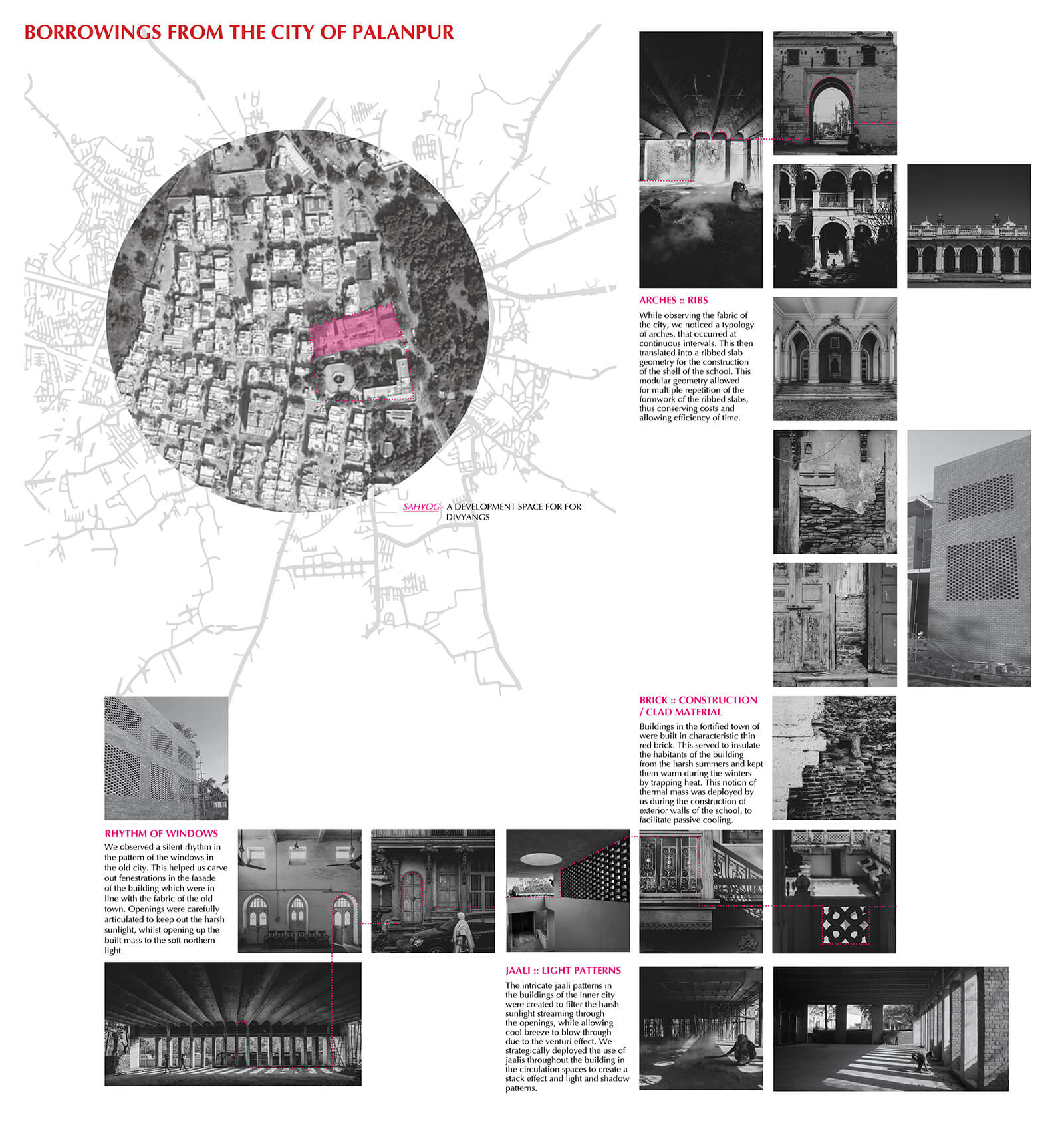

The fact that I never had a chance to visit Palanpur during my growing years created a sense of longing and curiosity. When the chance came to design this school, it went beyond its architecture; it was about reconnecting with a place that had shaped my family's legacy and exploring it through the eyes of a trained architect. This was a journey of rediscovery, where the city, its traditions and my roots came alive in new and unexpected ways. That Palanpur was a pioneer of black-and-white photography, with its nuances of light and shadow inspiring the incorporation of jaalis—added another layer to our narrative.

For me, this project wasn’t just an architectural exercise—it was a way to honour my heritage, re-engage with the city’s history and make a meaningful contribution to a community that needed a specialised environment. Each decision, from understanding the architectural fabric of the city to incorporating sustainable design principles, was informed by both my professional knowledge and the personal history of my family and hometown.

Dhwani: Since their inception, inclusivity has remained central to the Vidyamandir Trust and the Mamtamandir Schools’ philosophy. How was this ethos translated into the school’s architecture?

Nishant: The school, established in the 1960s, was a ground-breaking initiative in creating inclusive campuses for students with disabilities. Rooted in empowerment, the institution aimed to equip children with disabilities with practical, tangible skills that would enable them to integrate seamlessly into society. This vision extended beyond conventional education for Sahyog, where teaching and learning were deeply intertwined with hands-on, real-world applications.

The design for children prioritised the creation of diverse workshop spaces, tailored to help students enhance their motor and sensory skills. These were carefully curated to provide age-appropriate opportunities, from developing fine motor skills in younger students to teaching older ones practical trades such as news printing and carpentry. These vocational skills offered a pathway for students to gain confidence and independence, and earn a livelihood, fostering a sense of self-reliance and societal contribution.

The upper floors of the educational building included research spaces dedicated to training educators in specialised methods for teaching students. These spaces served as hubs of innovation, enabling the development of new teaching techniques and approaches that could be applied both within the school and beyond. This dual focus on student empowerment and teacher training made the institution a unique setup.

The design of the educational institute not only responded to the needs of its students but also redefined the purpose of educational space. It became a vibrant, inclusive ecosystem—a ‘living laboratory’ where every corner was designed to teach, learn and innovate. This forward-thinking approach not only nurtured the students’ abilities but also paved the way for a more inclusive and compassionate society.

Dhwani: With a limited budget ruling out active climate control, what passive strategies did you incorporate to address Palanpur's extreme climate?

Nishant: The building's design was meticulously crafted to address the challenges posed by the harsh climatic conditions and the constraints of a limited budget while ensuring a comfortable and supportive environment for the children. The southern facade of the Indian architecture was conceived as a buffer zone to shield its interior spaces from the intense sunlight and heat characteristic of the region. To achieve this, a circulation block extended along the southern side’s entire length, protecting the building's core from excessive heat gain.

An innovative design feature was the extensive use of brick jaalis along the southern face. This perforated brick architecture allowed hot air to escape from the central triple-height corridor, creating a stack effect that naturally ventilated the school building. Cooler air was drawn into the structure from the lower levels, significantly lowering the ambient temperature and reducing reliance on energy-intensive cooling systems.

The learning spaces were strategically oriented toward the north, where soft, natural light could permeate the interiors. This orientation minimised heat gain while creating a gentle, diffused illumination ideal for learning. Skylights punctuated the main corridor's spine, casting dynamic patterns of light and shadow that enlivened the school architecture. They also assisted visually impaired students, particularly those with photosensitive skin, by providing a natural, rhythmic guide that helped them orient themselves within the school. The result is a space both functional and sensitive to the unique requirements of its users.

Dhwani: Palanpur proffers a rich material heritage. How did you incorporate these traditional materials and reinterpret them to create a design language aligning with modern sensibilities?

Nishant: The design drew deeply from the architectural language and traditions observed in the surrounding cityscape. One of the most striking elements was the recurring typology of arches, which appeared regularly throughout the urban fabric. This inspired the adoption of a ribbed slab geometry for the school’s structural shell. By utilising this modular form, the design allowed for the repetitive use of ribbed slab formwork, optimising both time and costs during construction.

The rhythm of windows in the old city, subtle yet deliberate, further informed the school's facade design. The fenestrations were carefully carved to align with the architectural essence of the old town. Openings were positioned to block harsh southern sunlight while inviting the gentle northern light, creating a harmonious relationship between the built form and its climatic context.

The project’s material palette also drew from the historic townscape of Palanpur: The thin red brick, a hallmark of the fortified town, became an essential component of the school’s exterior walls. Known for its thermal mass, this material provided effective insulation, keeping the interiors cool during the scorching summers and warm during the chilly winters.

Another distinctive feature of the old city's architecture is its intricate jaali patterns, designed for both aesthetic appeal and functionality. These perforated screens filtered the harsh sunlight, creating intricate patterns of light and shadow, while simultaneously allowing the cool breeze to flow through, leveraging the Venturi effect. This principle was strategically incorporated into the school’s circulation spaces, where jaalis were employed to enhance passive cooling through the stack effect while casting playful patterns that added a dynamic visual layer to the spaces.

The school’s accessible design thus became a seamless blend of historic sensibilities and modern efficiency, deeply rooted in its context while serving the functional and aesthetic needs of its users. It celebrated the rhythm, materiality and passive design strategies of the old town, translating them into a contemporary architecture that was both sustainable and evocative.

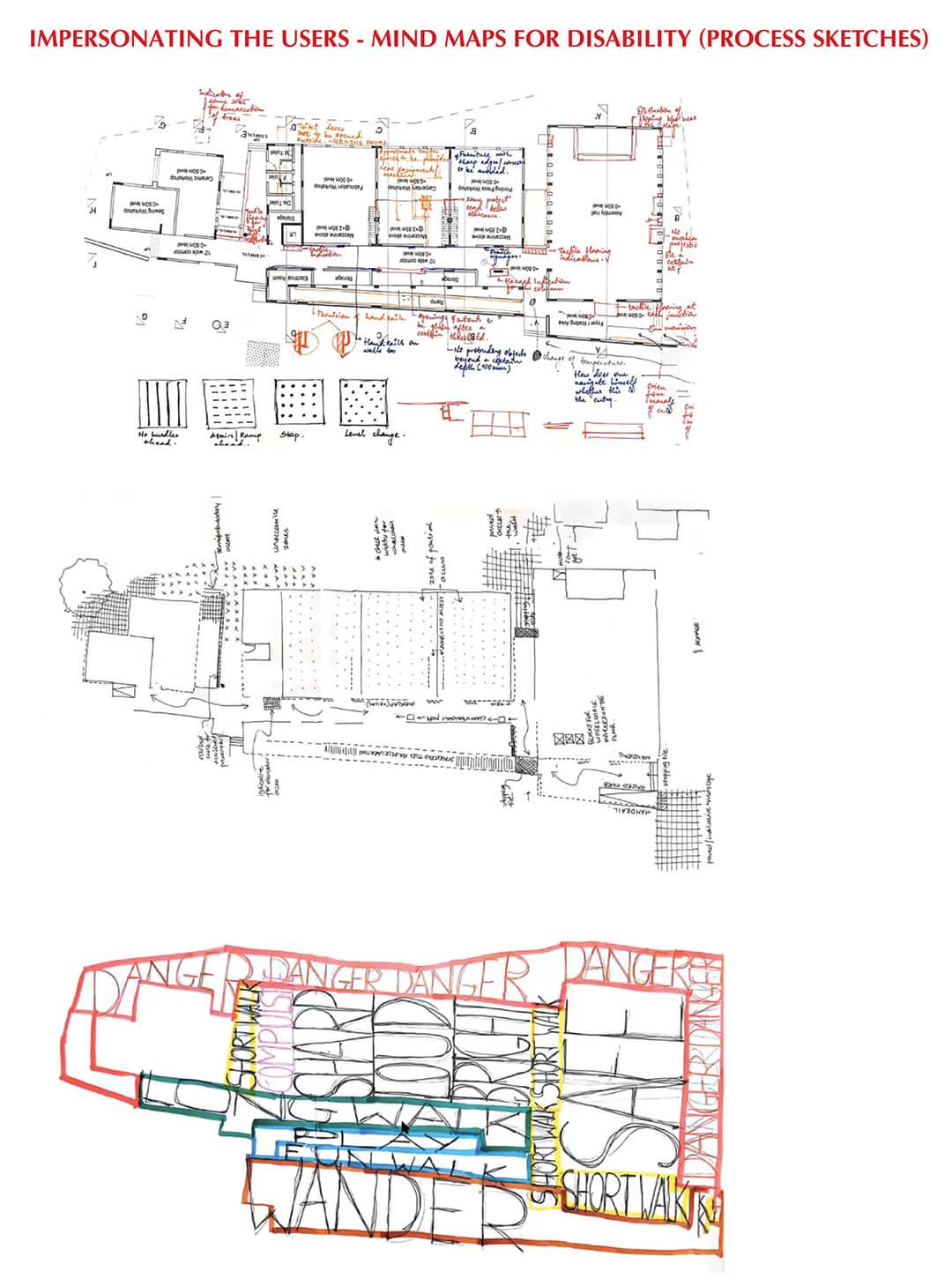

Dhwani: What research methods were used to develop design solutions ensuring safe, intuitive navigation and accessibility for the students?

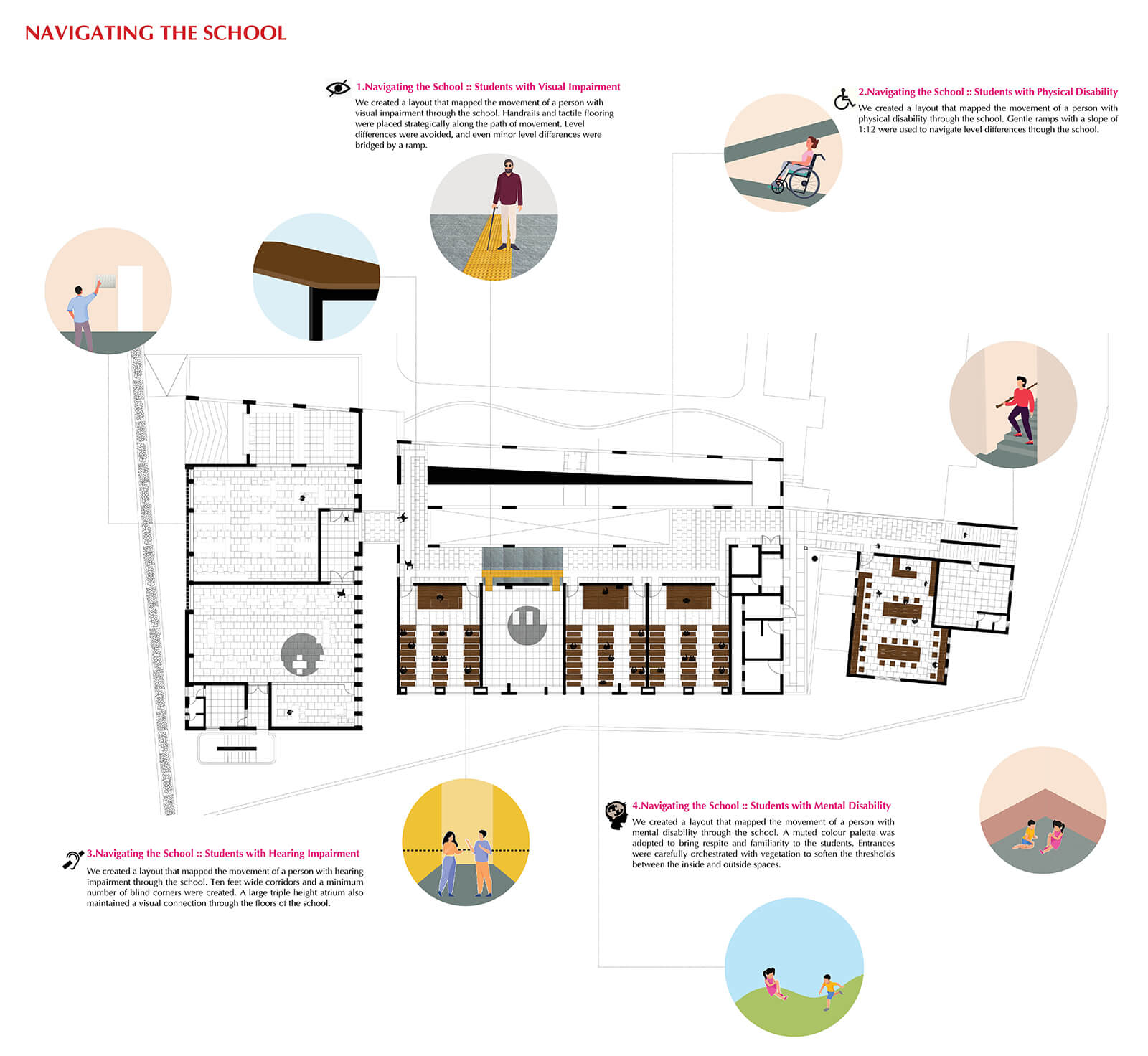

Nishant: The school’s layout was carefully designed to address the unique needs of students with various disabilities while fostering a sense of independence and comfort. It employed universal principles to create an environment that was accessible, intuitive and supportive of all users.

For students with visual impairments, the navigation through the school was enhanced by thoughtful spatial planning and tactile cues. The floorscape was designed with textured patterns, serving as a sensory map to guide movement. Handrails and tactile flooring were strategically positioned along key pathways of the sustainable architecture to ensure safe and independent mobility. Additionally, the school was planned on a single level wherever possible, eliminating major barriers, while even minor level differences were seamlessly bridged with ramps.

The needs of those with physical disabilities were addressed through gentle ramps with a slope ratio of 1:12, which ensured easy navigation across level differences, promoting unhindered movement throughout the school. Wide pathways and careful detailing ensured that no area of the school felt inaccessible.

For students with hearing impairments, visual connectivity and clear circulation were prioritised. Corridors were made 10 feet wide to accommodate hand gestures for signing while walking, ensuring smooth communication. The layout minimised blind corners, enhancing visibility and safety. A large triple-height atrium provided a central, open space that allowed students to maintain visual connections across multiple floors. This feature enabled them to observe the movements of peers, such as returning to classrooms after a break and adapting their routines accordingly.

Students with mental disabilities were supported by a calming and consistent spatial environment. The design employed a muted colour palette, fostering a sense of tranquillity and reducing sensory overload. Entrances were softened with curated vegetation, creating a welcoming transition between indoor and outdoor spaces. This careful orchestration of thresholds brought a sense of familiarity and comfort.

The landscape design further enhanced the students’ sensory experience, particularly those with visual impairments. Fragrant flowering plants were strategically planted at entrances, activating olfactory senses to signal key points of entry into the school.

Dhwani: Could you elaborate on the strategies used to engage the senses of touch, smell, sight and sound?

Nishant: The school’s flooring and circulation spaces were intricately tailored to enhance navigation, learning and independence, particularly for students with diverse needs. A thoughtful approach to materiality and spatial organisation transformed the flooring into a functional and sensory tool.

In the circulation areas, the flooring was rendered with a rough texture, distinguishing it from the smooth surfaces of the learning spaces. This contrast was especially beneficial for students with visual impairments, who often rely on heightened tactile sensitivity in their feet to navigate spaces. The textural differentiation created a subtle yet effective way for students to discern movement zones from learning areas, enabling seamless navigation through the school without external assistance.

In the workshops, the flooring became an educational medium. Polished surfaces were inlaid with colourful stones in primary shapes, offering a playful yet practical tool for learning. These patterns encouraged children to engage with the floorscape actively, blending the spatial environment with educational activities.

The main corridor, a triple-height sunlit passage, was conceived as Sahyog’s spine. Projecting balconies at various levels ensured ample visual connections across floors, fostering an inclusive environment for students with hearing impairments. These open sightlines allowed them to observe activities happening on multiple levels, helping them understand and participate in the school’s rhythm.

For students with photosensitive skin, the intricately designed jaalis served functional as well as sensory purposes. These perforated screens introduced sunlight into the building at specific times of the day, creating dynamic light patterns. Over time, visually impaired students were able to use these patterns as a natural clock, mapping the school’s organisation relative to time. This spatial-temporal awareness empowered them to orient themselves independently within the school.

The integration of these design elements demonstrated how small but intentional architectural choices could transform the built environment into an accessible, empowering and inclusive space. By addressing specific sensory and mobility needs, the school became a model for thoughtful and human-centric design.

Today, Sahyog stands as a testament to the enduring tradition of kinship and inclusivity central to the Jains of Palanpur. Embracing education as a key driver of the future, it aims to harness advanced technology and a scientific temperament as a tool for social upliftment. This small yet influential Jain-Gujarati community exemplifies how a bottom-up model, grounded in the principle of lifelong learning, can drive meaningful change.

Name: Sahyog

Location: Palanpur, Gujarat, India

Typology: Educational architecture

Client: Gemological Institute of America (GIA) + Vidyamandir Trust

Architect: Studio NM (Nishant Mehta, founder and principal architect)

Design Team: Aayush Vira

Area: 35,000 sq

Year of Completion: 2022

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dhwani Shanghvi | Published on : Dec 09, 2024

What do you think?