Advocates of change: revisiting creatively charged, STIRring events of 2023

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Manu SharmaPublished on : Feb 17, 2025

Saudi Arabia has seen multiple large-scale arts festivals and biennales launched in recent years, including the Diriyah Biennale (2020), Noor Riyadh (2021), the AlUla Arts Festival (2022), and the Islamic Arts Biennale (2023), which also comes under the Diriyah Biennale Foundation, a cultural institution affiliated with the Saudi Ministry of Culture (MOC). These events support the kingdom’s Vision 2030 initiative, launched by HRH Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The initiative seeks, among other objectives, to project Saudi Arabia as a regional centre for arts and culture.

The Diriyah Biennale Foundation is currently presenting the second edition of the Islamic Arts Biennale (IAB) at the Western Hajj Terminal of King Abdulaziz International Airport (KAIA), Jeddah. It runs from January 25 – May 25, 2025, and is organised under the artistic direction of Dr Julian Raby, Dr Amin Jaffer and Dr Abdulrahman Azzam, along with artist Muhannad Shono as curator of contemporary art. While both the Diriyah Biennale and the IAB feature Saudi and global practices, the latter places a greater emphasis on faith, which is evident even from the venues. The Diriyah Biennale is housed in Diriyah’s Jax District, which is a former industrial site near Riyadh that was developed as a contemporary arts and culture centre by the Saudi MOC. In contrast, the port city of Jeddah has historically served as a gateway to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, with the KAIA acting as a modern-day entry point for Muslim pilgrims undertaking Hajj and Umrah.

I think the choice of the term ‘Islamic arts’, the plural, really gives an idea of how there’s a desire here to welcome the collective. It is not (presenting) a single way of expressing what Islam is, but is welcoming different cultural interpretations of Islam and (Islamic) practices, and also new ideas for dialogue and transformation of space. – Muhannad Shono, curator of contemporary art, Islamic Arts Biennale

The second edition of IAB is titled ‘Wama Bainahuma’ (And All That Is In Between), a phrase that appears around 20 times in the Quran as part of a larger expression that proclaims God as the creator and ruler of the heavens and the earth, and all that is in between them. This state of supplication this entails is of great significance to Islamic art, culture and heritage (‘Islam’ itself means ‘submission to God’s will’), and so the expression has been chosen to emphasise a spiritual link between the exhibits at IAB.

The KAIA’s Hajj Terminal—completed in 1981 by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill to welcome pilgrims—reinforces the biennale’s Islamic identity as its canopies are inspired by the angular tops of bedouin tents, which traditionally housed pilgrims journeying to Mecca. The over 30 contemporary artists included in IAB support a sense of universality, ranging from local artist and filmmaker Anhar Salem, British-born artist Osman Yousefzada, who has roots in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the collective Slavs and Tatars, who are based in Berlin, Indian artist Asim Waqif and French artist of Algerian descent Abdelkader Benchamma.

The practices on view at IAB present their own articulations of Islamic themes. As the curator, Shono tells STIR, “I think the choice of the term ‘Islamic arts’, the plural, really gives an idea of how there’s a desire here to welcome the collective. It is not (presenting) a single way of expressing what Islam is, but is welcoming different cultural interpretations of Islam and (Islamic) practices, and also new ideas for dialogue and transformation of space.”

Salem’s art installation Media Fountain (2025) stands out among the works on display for its religious focus blended with new media technology. The faux fountain features a mosaic of anonymous internet avatars on its front facade, through which she examines the impact of globalisation on Islamic self-representation in contemporary cyberspace. These avatars reveal articulations of Muslim identity through popular aesthetics from around the world, such as those associated with Japanese animation. Once the installation’s tap is turned on, it projects a ‘stream’ of these avatars onto the visitor’s hand.

Yousefzada’s Arrivals (2022) is another noteworthy artwork resonating with themes of migration and homecoming. The installation is composed of sixty stools in the South Asian Peeri style, which usually features a wooden stool with short legs. Yousefzada’s chairs feature traditional Pakistani textiles for their seats and are available for audiences to remove from their stacked singular form and use as seating. Yousefzada discussed the artwork in an interview with STIR, saying, “So it continuously unpacks throughout the day, and then at the end, it’s relocated to its nucleus.” The work comments on the international migration of Muslims, either in pursuit of work or to seek refuge from geopolitical conflicts. Touchingly, at the end of each day, these dispersed chairs are metaphorically returned to a state of oneness.

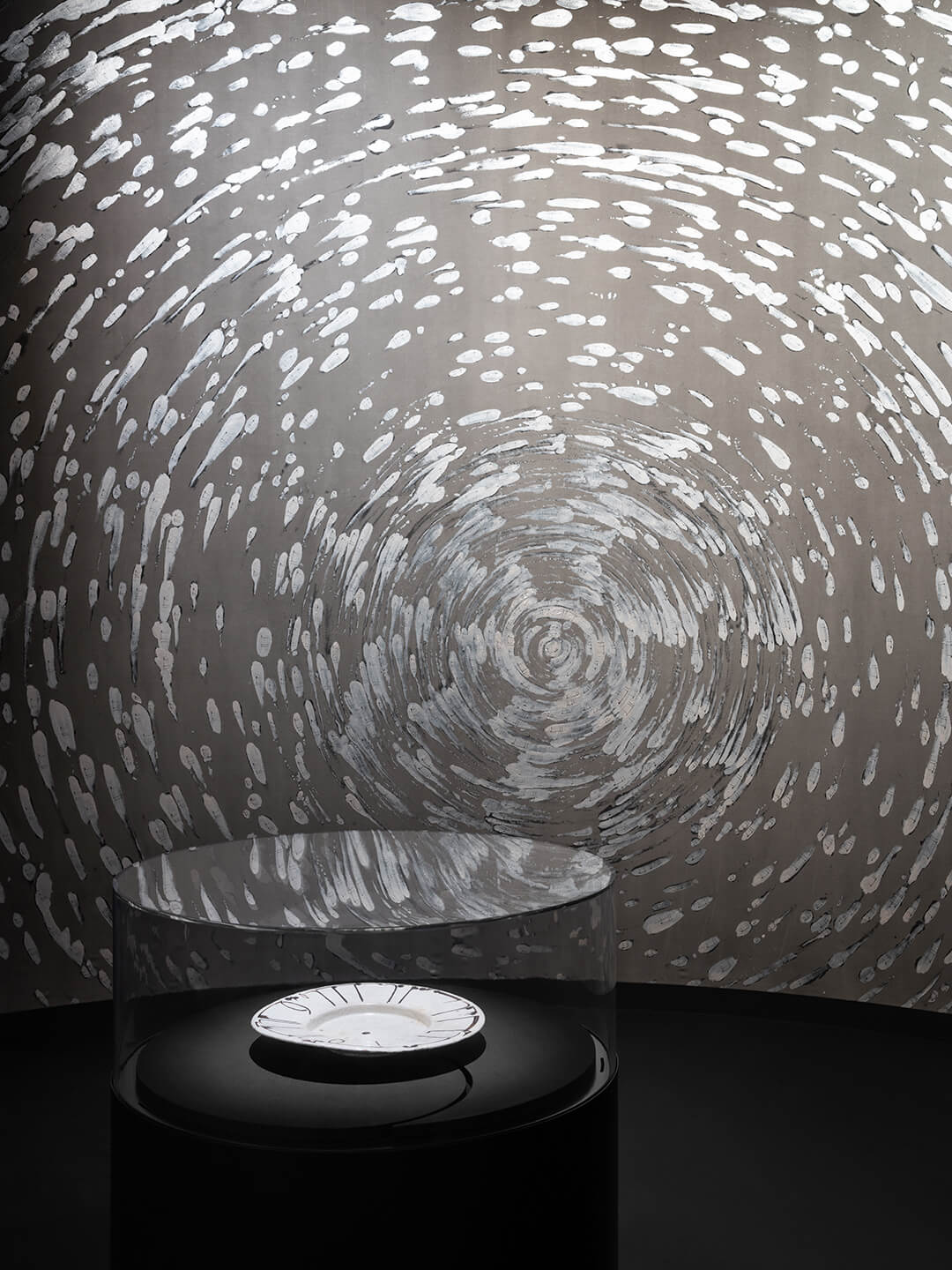

Not all the artists included in the exhibition are Muslim. Taiwanese artist Charwei Tsai spent time in her youth honing her calligraphy skills through Buddhist scriptures, which she eventually memorised. Her artwork That Which at First Tastes Bitter (2025) is composed of a ceramic dish from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, that dates back to 975 – 1000 AD, placed before a painting by the contemporary artist. The dish contains a black dot in the centre and is surrounded by Kufic calligraphy (the oldest Arabic calligraphic script), which reads, “Magnanimity is at first bitter, but ultimately sweeter than honey. Good health.” Tsai’s painting resembles a cosmic body, such as a galaxy, that radiates outward. Each dot is made from mother-of-pearl pigment and bears the repeated inscription ‘Al-Hilm’ (patience, tolerance or knowledge), which she has extracted from the first character of the inscription. The artist’s painting responds to the dish by inviting audiences to contemplate its essential message.

Japanese artist Takashi Kuribayashi’s large-scale art installation Barrels (2024) features a single tree appearing to float on a barrel, flanked by other barrels. In an interview with STIR, Kuribayashi explains that he wished to explore a critical relationship between nature and oil. The tops of the barrels hold circular mirrors, and when we observe the barrel holding the tree, we see it reflected in a mirror under the canopy of the Hajj Terminal. This suggests that vegetation from above (ground) eventually becomes oil below. However, when placing the artwork within a Saudi context, it is difficult not to read it as a meditation on the harm that oil extraction causes to the environment. As the world’s largest oil exporter, the kingdom is particularly implicated in the ongoing climate crisis, with its national oil company Aramco acting as the world’s largest contributor to climate change.

Contemporary art is a smaller element of the biennale than the historical Islamic artefacts being shown, which are exhibited by over 30 international institutions. It is organised around seven components (the fair’s term for ‘sections’). The first is ‘AlBidayah’ (The Beginning), which stretches across multiple indoor gallery spaces and prompts audiences to contemplate the divine through an Islamic lens. AlBidayah is palpably serene and presents artefacts from Mecca and Medina, such as copies of the Quran from Morocco and Egypt from the 14th century.

The second component is ‘AlMadar’ (The Orbit), also indoors and appropriately named as it features historical cartographic, astronomical and timekeeping tools from institutional collections stretching across over 2000 years, including a richly detailed Malay calendar from the 13th – 14th century from the collection of the National Library of Indonesia. This space also features contemporary artworks such as the aforementioned That Which at First Tastes Bitter, which complement the cosmological themes of the space.

Continuing indoors, the third component is ‘AlMuqtani’ (The Homage), which presents two of the largest collections of Islamic artefacts, those of Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani and Rifaat Sheikh El Ard. The former contains many precious objects and musical instruments. Meanwhile, the latter presents arms and armour from the Islamic world, including bespoke sets of imposing chainmail dating back to the mid-15th century. While both collections are invaluable bodies of cultural heritage, the collection of Rifaat Sheikh El Ard does create tension when read in relation to the other exhibits at the IAB. The violence of religious expansionism is hardly unique to Islam. However, presenting this collection at the fair may subvert the IAB’s narrative of enlightenment and play into problematic Western tropes surrounding the religion.

Moving into the open, the fourth component of IAB is ‘AlMidhallah’ (The Canopy), an outdoor garden in the charbagh style, which features intersecting walkways. AlMidhallah houses the bulk of IAB’s contemporary art, including the aforementioned works by Salem, Kuribayashi and Yousefzada. The four quadrants are arranged according to various themes intersecting nature and community. The first, ‘Gateway & Pathway’, represents the crossing of the threshold into a garden and features movement-related works such as a film by Saudi dancer and filmmaker Bilal Allaf. The second quadrant is ‘Understanding & Knowledge’, where research-based works such as Salem’s Media Fountain are placed. The third is ‘Contemplation & Rejuvenation’, which contains meditative works such as Kuribayashi’s Barrels. AlMidhallah’s final quadrant is ‘Congregation & Community’, and features works tied to themes of collectivity, such as Yousefzada’s Arrivals.

Moving indoors again and onto the biennale’s fifth and sixth components, titled ‘AlMukarramah’ (The Honoured) and ‘AlMunawwarh’ (The Illuminated), the IAB highlights Saudi Arabia’s stewardship of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. These sections contain artefacts connected to these cities, like massive gold-embroidered drapes that once adorned the Prophet’s Mosque and photographs by Mecca’s first photographer, Abdulghaffar Albaghdadi Almakki (d. 1902), whose works were unfortunately plagiarised by the Dutch colonial officer Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. The photographs document the city of Mecca, which had a sprawling infrastructure around the turn of the twentieth century despite the transient nature of many of its inhabitants. AlMukarramah and AlMunawwarh are both permanent pavilions, which will presumably remain open to Muslim pilgrims travelling for Hajj and Umrah well into the future.

The final, outdoor component of the biennale is ‘AlMusalla’ (A place of Prayer). The AlMusalla Prize was launched in 2024 by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation to highlight contemporary architecture in Islamic spaces of worship. The inaugural AlMusalla prize is shared collaboratively by EAST Architecture Studio, which is based in Lebanon, and Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet. They collectively presented their modular musalla at IAB. The structure is created through Middle-Eastern weaving traditions and sustainable support structures created by pressing together date palm fronds and fibres.

The Islamic Arts Biennale is a sprawling presentation that resists a singular reading. It certainly aids Saudi Arabia’s objective of building artistic and cultural primacy within the region, which is to be expected, given the Diriyah Biennale Foundation’s support from the wealthy Saudi government. Simultaneously, much of the exhibition successfully showcases Islamic enlightenment, countering Western narratives around the religion and the Middle East. However, one must consider carefully whether the government that supports the biennale itself conforms to the spiritually driven, pluralistic and environmentally harmonious values highlighted at the biennale.

The Islamic Arts Biennale 2025 runs from January 25 – May 25, 2025, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

(The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Manu Sharma | Published on : Feb 17, 2025

What do you think?