The House of Mango Shadows frames a contemporary Indian retreat amidst greens

by Nikitha SunilJul 10, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Jincy IypePublished on : Feb 23, 2024

Section 4. The Object:

The objects, of the University shall be to disseminate and advance knowledge, wisdom and understanding by teaching and research and by the example and influence of its corporate life and in particular the objects set out in the First Schedule.

The First Schedule:

The University shall endeavour to promote the study of the principles for which Jawaharlal Nehru worked during his lifetime, national integration, social justice, secularism, democratic way of life, international understanding and scientific approach to the problems of society.

Thus reads a portion from the Jawaharlal Nehru University Act, 1966 (53 of 1966),1 introduced in the Rajya Sabha on September 1, 1965, by M C Chagla during his tenure as the Education Minister of India, with ambitions of setting up a centre for higher learning, and one of international standards. Bhupesh Gupta, a senior communist leader and parliamentarian in the Rajya Sabha, spoke in motion of the bill2 which subsequently outlined and defined the inception of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Gupta’s impactful speech in the parliament essentially transformed this bill, excerpts of which mentioned:

The very first thing that comes to my mind in this connection is: for whom we are arranging this education…This question is very important and has to be answered and settled from the standpoint of those who need the care of the country most…

…let us create universities and colleges that our people need, that our development needs, for the remaking of our material and cultural being.

…I think we can give autonomy in a larger measure to a university of this kind. Since Jawaharlal Nehru’s name is associated with it[,] I feel there should be faculty which educates the students in the spirit of world power.

…I would also like this university to educate students on various matters connected with the development of democratic institutions and democracy in the country. This should be a special subject.

Once this need for a specific and specialised educational institute was established through the JNU Act, 1966, and following Gupta’s ensuing speech, a democratic body was set in place wherein the university was granted fundamental autonomy, giving it the opportunity and power to float the first National Architectural Competition to be held in post-independent India for its realisation. The prescient proposal by late Indian architect CP Kukreja, (aged 32 years at the time) expanded on and parallelled this objective, and was declared the winner by an esteemed jury in 1969. This monumental win became the first significant commission for the then two-person firm.

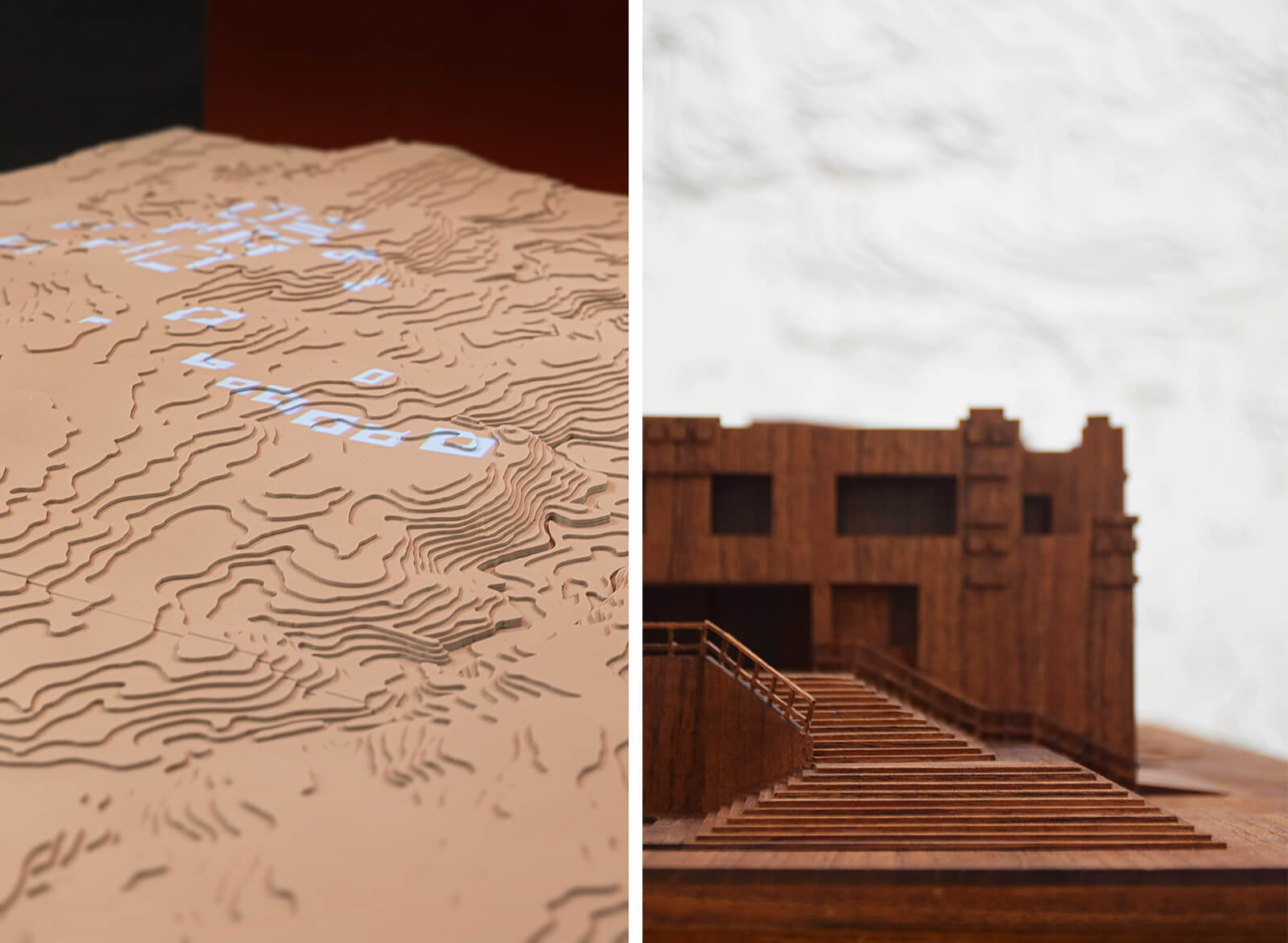

The project’s initial masterplan catered to the calling of the expansive 1,000-acre site, embracing ‘intellectual exploration’ as its chassis and core. 50 years later, The Masterplan, a project by the CP Kukreja Foundation for Design Excellence, and curated by Indian artist and architect Vishal K Dar, commemorated this transformative effort at the India Art Fair 2024 by revisiting JNU’s architectural legacy. The exhibition, held from February 1 – 4, 2024, explored the intersections of architecture, climate, and nation-building through ‘visual chapters,’ delving into narratives that shaped post-independence India for generations to come.

The soil-red pavilion within the art fair showcased meticulously arranged compositions of previously unseen architectural drawings, documents, photographs, diagrams, and physical models depicting the contoured site and its built forms. This deliberate parallel echoed the exposed brick structures of the Indian architecture and its vast, contoured site characterised by red Aravalli soil. The creators of The Masterplan emphasised their intention to share their journey while adding to architectural pedagogy, the makings of collective spaces, and the history of modern India.

Architecture has always played a vital role in the history of civilisation-making. It has been many things—a document of its times, a mirror of its makers, a time capsule. – Vishal K Dar

“The exhibition focuses on the emergence of the first South-Asian attempt at creating a vast university model—JNU—where an institution is imagined as a micro-city within the southern ridge of the Aravalli hills of New Delhi. Here, on these grounds, India would cultivate students who would learn to interact and dialogue with the world,” they continue.

The neat exhibition design, conceptualised as a studio within a pavilion, offered both ‘didactic and experiential’ elements, inviting visitors to engage with the site's geology and contextual architecture. Through this experience, the exhibition space illustrated how the natural landscape's ecology and climate influenced the strategies employed by the architect to shape, respond to, and align the built environment.

JNU's realisation reflected diverse aspirations shaping a nascent democracy, as India embarked on a journey of self-discovery. This endeavour resonated with Nehru's tangible vision of nurturing the nation’s citizens who would propel India onto the world stage. The masterplan thus unfolds this ‘vision’ on multiple levels, encompassing the role of the state, the architect, and the site.

In dialogue with STIR, Dar elaborated on the genesis of The Masterplan: He observed a gap in recent exhibitions focusing on Indian modernist architecture, particularly the oversight of the JNU campus' impact. Subsequently, he proposed to CP Kukreja Architects (CPKA) to access their design archive for creating an exhibition on this seminal project. However, he discovered that much of the archive was missing, having been lost over the years. Another proposal was then put forth to CPKA to reconstruct the archive, which ultimately became the primary source for The Masterplan’s narrative.

The title of the architectural exhibition, according to the curator, is positioned upon two registers: Firstly, it originates from a pivotal discovery within the initial archive—a sole surviving document, a line drawing of the early project's masterplan. Additionally, the term ‘masterplan’ encapsulates the concept of a detailed plan of action geared towards making a complex project successful, of consolidating multiple plans into a unified reference towards a broader perspective. In this context, the architectural masterplan is precisely this continuation, embodying the essence of the term's definition.

Even beyond the realm of architecture, the term holds due relevance when used in other contexts, including politics, of putting any and all elements related to a larger vision under a cohesive expression, to facilitate understanding and alignment with overarching objectives.

The hierarchical process of JNU's inception enriches the significance of the exhibition's moniker, reflecting the masterplan inherent in both, the legislative framework and the subsequent speech, grounded on the ‘vision’ of the architect of modern India, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, with JNU being part of his masterplan from the start. Therein, for an architecture of this scale to come into existence, before its own masterplan was devised, a bigger one was already in play, one of a more ideological nature.

Every masterplan, thus, is a prophecy, whether they resist inequalities or end up perpetuating divisions. As an autonomous institution, JNU embodies the spirit of its ideological architect, envisioning its future as a tangible built space furthering culture and education. Thus, the consistent usage of the term ‘masterplan' in this narrative underscores its interconnectedness and coherence throughout.

A university stands for humanism, for tolerance, for reason, for the adventure of ideas and for the search of truth. – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

The deliberate, open-access displaying of The Masterplan at the India Art Fair this year also refers symbolically to the democratic ethos underlying the institution's establishment, and its ongoing commitment to equitable nationwide knowledge dissemination. Dar elaborates on his choice to complement the exhibition with enlarged prints of the JNU Act, 1966, and Gupta's ensuing speech, by citing examples of the autonomy granted to other national institutes of higher learning such as IIT, IIM, NID, SPA, or NSD—entrusted with self-governance rights for a reason. Preserving the Act as well as the transformative speech, not merely as an exhibit but as a communicative object on display highlights the significance of these autonomies, granted by our parliament not only as constitutional measures but as profound actions taken by individuals invested in nation-building during the nascent stages of our republic.

The cherished exposed brick edifices of JNU's campus, rooted in Nehruvian principles, remain remarkably relevant today among the most sustainably designed structures. Responding to its distinct rocky terrain, the campus’ design, choice of materials, and forms seemingly sprouting from the earth, resonate with its natural surroundings, embodying an ethos of intellectual advocacy intertwined with environmental stewardship—a pioneering concept at its inception.

Over decades, JNU’s campus has transformed from barren land to a thriving, verdant ecosystem, a metaphorical demonstration of knowledge begetting prosperity. The rich biodiversity of the ridge, with over 200 species of flora and fauna, has evolved in response to its unique landscape. In embracing nature, the campus exemplifies a non-regimental ethos, honouring its promise to the land to come into its own, to partner with and help the built.

The project’s brief (developed by JNU as an autonomous body) is a remarkably detailed document according to Dar. This reflects an intelligent client prioritising academic discourse grounded in exploration, exposure, and self-questioning. Another metaphor for the project’s growth and abundance rests on the fact that a young architect won an architectural competition of this scale, showcasing not only his competence but also the discernment and cultural acumen of the jury—the project’s credit extends much beyond the firm that executed it. It encompasses the entire making of it, from the bill to the site.

“The exhibition also ignites discussions surrounding the architect’s role and their vision of architecture in nation-building. In a world where prestigious universities defined their presence through classical forms and regimental standards, JNU’s masterplan, in its uniqueness, reflects an absence of the built. Like water, the built environment finds its way into the landscape,” Dar elaborates.

The Masterplan also investigates the nature and role of an architect in the critical exercise of nation-building: the term ‘architecture’ or ‘architect’ is often bequeathed meaning differently depending on context. When it comes to forms, they are integral components of the overarching plan being formulated and not the protagonists. Consequently, the investigation at the art event sheds light on the critical role of the architectural entity and its author—highlighting that "an architect is about what precedes, not what succeeds," as Dar observes.

This role, if correctly perceived, is defined because there is a need for it. In the case of JNU, the establishment of a specialised centre for higher education arose from a recognised need within a democratic framework. Through policy-making and subsequent planning, the university was created. Before the architecture or the architect, this need was the driving force behind the project.

The curator also considers how the architect is a non-entity until they choose to become an entity—the role of an architect in society is largely self-defined, transcending the limits or liberties imposed by their projects and their clients. In a public architecture like JNU's, architects cannot navigate with full autonomy, where their political or ideological beliefs colour the built, a fact that requires objectivity to realise. Essentially, architects are service providers. This profession has survived for years through the profound act of designing refuge, wherein the author seldom dictates each line.

Therefore, the state bears the responsibility of accommodating architects, while they reciprocate with their services. In the case of JNU, there's inherent value in understanding the continuity of a vision shared across levels and generations, with architects contributing to the process of nation-building. According to Dar, the role under investigation seeks to comprehend the nuances of how architects engage—initially through participation and subsequently through action and implementation—in specific briefs shaped by forces beyond the confines of architectural practice.

References

1.Courtesy of the Jawaharlal University, New Delhi (available here)

2.Courtesy of the Penguin Book of Modern Indian Speeches: 1877 to the present, 2007

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Jincy Iype | Published on : Feb 23, 2024

What do you think?