Studio Sangath's recent residential design revels in the brutalist materiality of brick

by Mrinmayee BhootJun 10, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dhwani ShanghviPublished on : Jul 27, 2024

In the decade preceding the economic liberalisation of India in 1991, the image of a universally placeless architecture—functional, pure and free of ornamentation and historical references that had become a symbol of Nehrus’s vision of a socialist modernisation programme—was being put into question. By the 1970s-80s, an entire generation of overseas-educated postcolonial Indian architects who shaped the built environment of Independent India were on a quest to distinguish a vivid Indian identity within the larger movement of modernism. Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi, who had previously worked with Swiss architect Le Corbusier in his Parisian atelier and was influenced by the European avant-garde modern architecture, played a central role in the nation-building efforts in the years immediately following the independence of India.

Establishing his own architectural practice, Vastu-Shilpa (later renamed Vastu Shilpa Consultants) in 1955, Doshi’s later works illustrate emancipation from Corbusier’s ‘utopian’ Modernism. The works of BV Doshi, Achyut Kanvinde, Charles Correa, Raj Rewal, Anant Raje etc today serve as a repository of Modern Indian Architecture - a modernism of courtyards and shaded terraces, a modernism of streets and markets, a modernism of intimate proportions and north light, a modernism of thresholds and thoroughfares, blending elements from the Modern Movement with indigenous traditions.

However, while a unified national identity for an Indian architecture is desirable, India's vast regional, climatic, geographical, cultural, and religious diversity has resulted in significant variations in building materials, construction methods, and design approaches. In this context, the quest for an identity rooted in place is an empirical process of rationally and logically reflecting local building and construction traditions without resorting to imitation, while also versatile enough to meet the demands of building typologies. In the to-day, Studio Sangath, led by Khushnu Panthaki Hoof and Sönke Hoof, has shifted its focus from seeking a singular Indian identity to developing an architectural language that embraces region-specific lifestyles, influenced by local craftsmanship and microclimatic conditions.

In the village of Devdholera, about 40 km from the city of Ahmedabad, the Terra Pavilion is located on the site of Kensville, a 900-acre golf course and residential development by the Savvy Group. Khushnu and Sönke evolved the design for the house from a desire to have an unrestricted integration with the surrounding landscape, including the greens of the golf course. The concept for the project stems from the rather elemental act of segregating the architectural program into social and private, split across two levels. Built for the clients Himangini and Sameer Sinha, the project brief called for spacious gathering areas and three bedrooms to accommodate the couple and their two sons, outlining spaces for social activities and private relaxation. The vision for their home—“to create a contemporary minimalist space that is both inviting and joyful, serving as a sanctuary for their family to thrive” is thus symbolic of the lifestyle of the dynamic duo—Himangini a technocrat who transitioned to farming as well as crafting artisanal cheese, and Sameer, the founder of the Savvy Group.

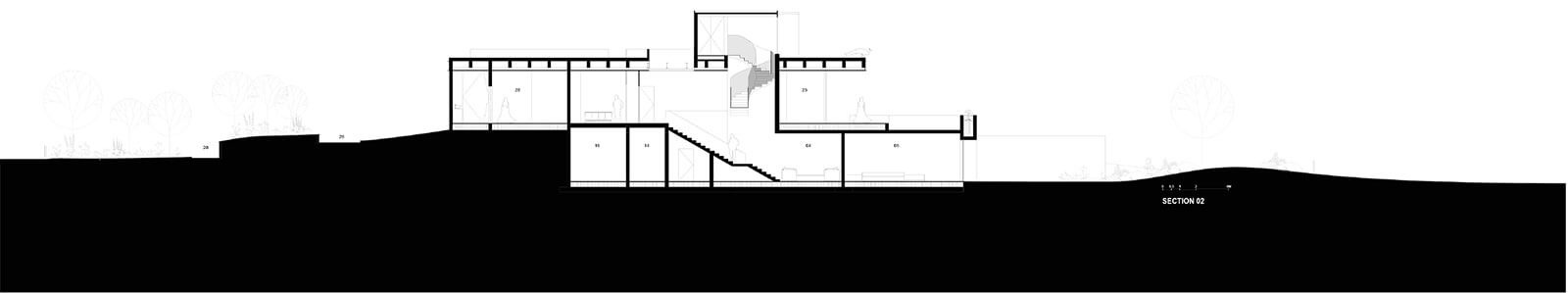

This seemingly simple segregation of the outward-facing social and inward-facing private across two levels is sublimated by creating distinct binaries between the public and the private, aided by the gentle slope on the site. The former, accessed through a serpentine forest path, unveils itself from behind the natural contours of the landscape as a hovering volume over the undulating terrain, while the private zone is nestled within the earth, serving as a plinth for the pavilion above it. It is in this moment of observation that the residence’s nomenclature comes undone with the earth level hoisting the pavilion level - Terra-Pavilion.

Serving as the level of entry, the pavilion—a typology somewhat uncommon in residential architecture—is conceived with an open plan constituting lounge areas, dining spaces, an open island kitchen and study, enclosed within a glass volume interspersed with slender steel columns. The journey from the entrance to discovering the spatial quality of the pavilion manifests a sense of mystery as one progresses from a compact corridor flanked by concrete walls that expand to both, being affronted by a curved concrete mass, and revealing a small section of a glass wall of the kitchen area towards the right.

It is only as the eyes turn left that the almost void-like space enclosed by glazed walls comes to light, affording a panoramic vantage of the golf course. The roof, with its expansive timber slates forming the soffit, extends outward to create shaded verandahs beneath its cantilevered cover. The internal exposed concrete walls (left in a natural finish on this floor), which enclose the services and staircases within its mass, also demarcate the volume into two sections broadly - dining and lounging. More importantly, here is a perfect illustration of the riddle: How does one make a line drawn on a paper smaller in length without erasing it? By drawing a longer line near it. The mass, in this case, manifests the relativity needed to draw out the pavilion-ness of the space around it.

Inversely, the earth level is a solid mass of exposed concrete - almost brutally so. Burrowed into the terrain, the load-bearing structure crafts geometric masses from a series of concrete shear walls along the perimeter, encompassing a form defined by deep thresholds and few or no openings that can peep into the family room or the three bedrooms that it encloses. Here too, the stark contrast with the pavilion on its roof, which is a framed structure enveloped by curtain walls, is emphasised.

The earth level embraces a robust aesthetic, featuring black-pigmented concrete elements that allude to the darkness of the subterranean world. On the west and north, deep thresholds seamlessly continue beyond the room they abut to meet the landscape, the contiguity accented by the extension of the flooring and wall beyond the interior space.

But within this subdued, intimate space, the service core is a theatrical revelation of an architectural narrative expressed in sculptural form. A straight flight of concrete steps leads to the earth level from the floor above. A second staircase - floating, spiral and painted a stark black ascends to the sky level, which houses a roof garden of sorts. Here is a space where different materials and textures interact to celebrate the symphony between light, colour and mass; where the two distinct finishes of concrete—natural and black pigmented—interlock, where a red staircase handrail and a black spiral staircase structure coalesce; and where a sharp ray of light underscores the rivet marks on the concrete wall.

The levels of the house, planned as such to engage with the surrounding landscape and the golf course beyond, however, appear to have a somewhat hands-off relationship with the greens. While the edges of the house extend to meet the manicured landscape, it is an encounter that feels more visual than tactile.

The Terra Pavilion is thus a building that is both universally placeless and deeply rooted, for it is an architectural language that strongly invokes modernism’s Indian-ness so familiar to Ahmedabad. And while one may inadvertently reminisce on the tactile intimacy of the transient spaces of Doshi’s buildings—the gentle breeze from a north window, flowers from his beloved champa tree on a paved floor, light from clerestories—the intimacy here is invoked through an image of the Sinhas’ crafting artisanal cheese while enjoying views of the fair-fields in the background, an Indian-ness derived not from the search for postcolonial identity but rather a post-liberalisation and global context, an Indian-ness nonetheless.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dhwani Shanghvi | Published on : Jul 27, 2024

What do you think?