‘Web(s) of Life’: An evolutionary tapestry at Serpentine Gallery

by Sakhi SobtiJul 11, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Tabish KhanPublished on : Feb 26, 2024

What is it like to play chess when the board and both sets of pieces are white? Visitors are invited to do just that. The game gets confusing very quickly and even if one player can checkmate the other, without losing track of which pieces are whose, either way, white has won. Chess becomes a game about enjoying the process of playing and living—a central theme in Yoko Ono’s work. It’s one powerful work in Tate Modern’s major Yoko Ono retrospective curated by Juliet Bingham, curator, International Art, Tate Modern; Patrizia Dander, Head of Curatorial Department, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen with Andrew de Brún, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern and Catherine Frèrejean, Assistant Curator, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

The artist’s reinforcement of positivity is expressed through a set of wish trees outside the exhibition where people can write their hopes to hang on a tree, replicating those that Ono remembered from her childhood spent in temple courtyards in Japan. This hope for a better future complements one of the most poignant participatory works inside the exhibition where visitors can write dedications to their mothers—many of them are moving tributes to those who have passed away and some visitors have even hung photographs of their mums on the wall.

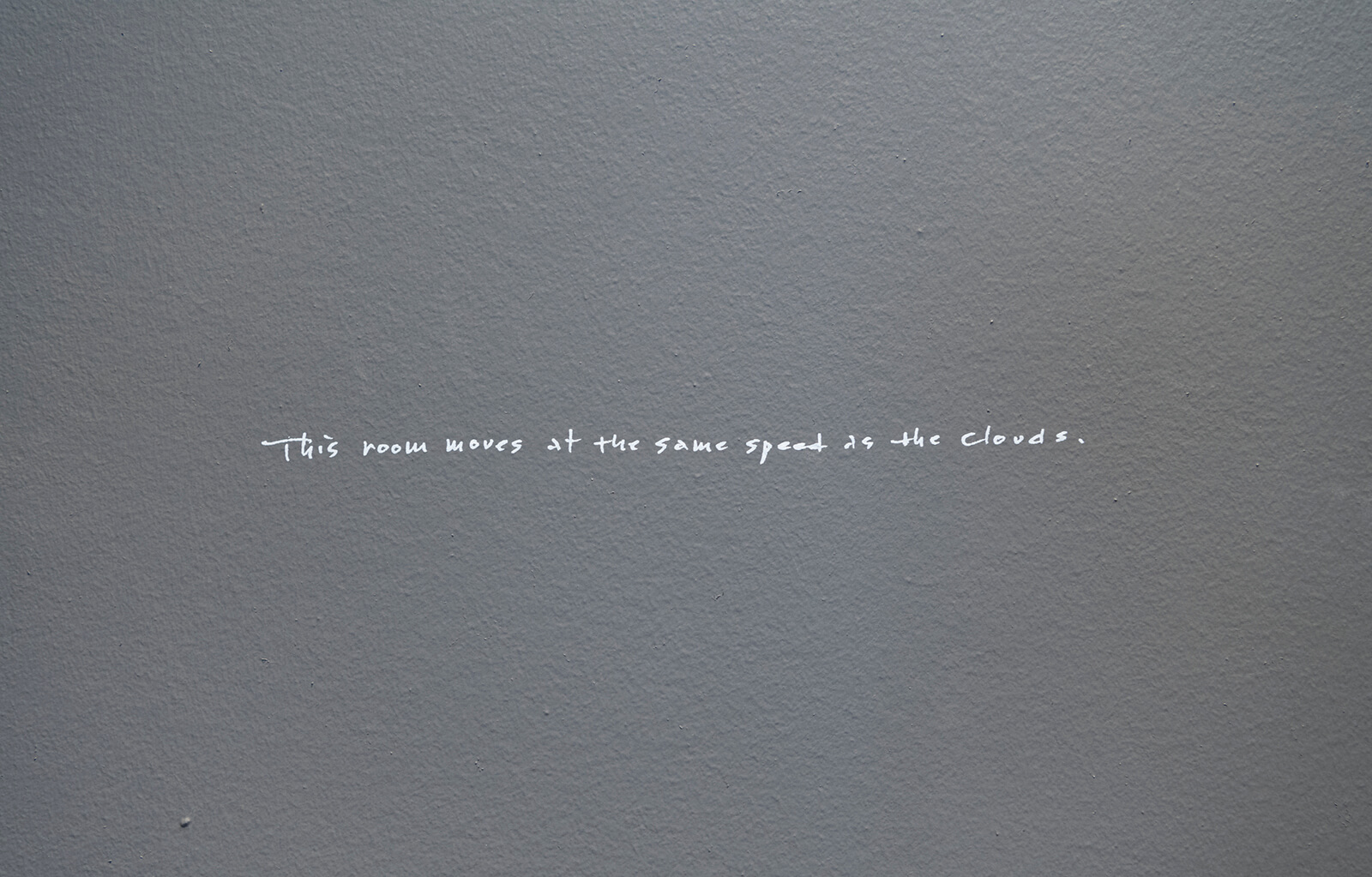

Affirmations of peace and love might seem trite in the hands of many other artists, but they retain their power in Ono’s, given that she grew up amid World War II, evacuating Tokyo amidst US bombings in 1945 at age 12. She remembers staring at the sky with her brother and escaping into their imaginations, an act she describes as “maybe my first piece of art”. This poetic nature finds its way into much of her work, including on entering the exhibition with the line "this room moves at the same speed as the clouds" scrawled on the wall.

Ono’s belief in peace feels relevant today given ongoing wars around the world, and her message is infectious. In one room, the audience is invited to write in blue all over the walls, the floor, and a replica of a refugee boat; while visitors are free to write what they want, all we see are messages urging for peace and reconciliation. Just outside this room, one of her works presents a pane of glass, shot through with a bullet, and we see the cracks spreading through the glass, which can be read as how violence itself is also infectious.

Participation is key to Ono’s work even as some pieces can now only be shown through archival videos or documentation. In the show, we read about how she and John Lennon sent acorns to world leaders so that they could plant a tree and give life rather than take it away. Still, the exhibition ensures there are opportunities for visitors to engage, say by hammering a nail into a painted board, with Painting to Hammer a Nail giving participants a sense of creating artwork through a normally mundane action. Visitors can also cover themselves in black cloth in Bag Piece (1964) and sit, lie down, or even enact their performance whilst remaining anonymous to other viewers until they remove their black cloaks. These interactive elements make Ono’s work easy for museum visitors of all ages to relate to, and during our visit, many children were immersed in the participatory elements.

This doesn’t mean that every work resonates; a section dedicated to her albums, where visitors can listen on headphones, largely felt neglected by audiences. When we listened in, the experimental audio didn’t leave a lasting impact like Ono’s visual artworks. It’s also fair to question whether her view of peace and love for all is possible in a world where crime and violence are an everyday occurrence, though there’s no denying that Ono’s belief in her vision for world peace has been a constant in her decades as an artist.

While the quote attributed to Plato “only the dead have seen the end of war” may remain true, Ono’s work and life are a reminder that there is another way through peace and the simplest of life’s pleasures, from watching a match burn in slow motion to playing a game of chess. The message she conveys will strike a chord with any visitor and is likely to touch the hearts of even the most cynical gallery-goer—it’s a reminder that art is a force for good and that it can change the world.

'Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind' is on at Tate Modern in London until September 1, 2024.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Tabish Khan | Published on : Feb 26, 2024

What do you think?