Reflections, reclamations: On glass, Edith Farnsworth & Almost Nothing by Nora Wendl

by Mrinmayee Bhoot, Chahna TankJun 26, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Sep 26, 2024

If you are a design enthusiast, an architect obsessed with the utopian promises of modernism, an architectural historian interested in the influence of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and the Saarinens on American architecture, or, oddly enough, a fanatic of indie films from the late 2010s, chances are you are familiar with the significance that Columbus, Indiana, holds in the history of American modernism. Columbus, a town of approximately 50,000, quintessentially mid-Western, less than three hours from Indianapolis and headquarters of the Fortune 500-listed engine company Cummins, is also considered a mecca of modern architecture. That the town should be considered a bucket list item for any avid lover of architecture and design is obvious from the rich roster of architects who have left their mark on the town’s urban fabric: from the aforementioned Saarinens (both father and son), Harry Weese, I.M. Pei, César Pelli, Kevin Roche and Robert Venturi, to the more contemporary Carlos Jimenez, Deborah Berke and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, to name a few.

A recent book details the many-layered histories of the city’s conception and development; unravelling the civic, industrial and social conditions that would converge to create “the very best community of its size in the country," as J Irwin Miller, the late former chairman and CEO of Cummins and the city’s biggest benefactor hoped. Written by Matt Shaw, an architect and native of the town, it chronicles how design was instrumental in fostering a sense of community in the city, with Miller and his contemporaries’ patronage turning it into a hotbed for innovative design. As Shaw argues, Columbus represents a microcosm of American post-war ideals reflected in its built environment and urban design and planning discourse. By connecting the history of the town to its present, the hope is to present “Columbus [as] not just a museum of individual buildings, but rather an ongoing project that encapsulates the entire city,” Shaw writes in the introduction.

Today, how the local community relates to the bastions of an alternate vision of the country is what Richard McCoy, founding director of Landmark Columbus, a heritage foundation dedicated to caring for and carrying forward the modern legacy of Columbus, might term “progressive preservation". For instance, Miller’s residence designed by Eero Saarinen opened to the public in 2011 after the passing of Miller and his wife, following on the inclination for structures of architectural significance to be accessible to visitors as a form of cultural tourism. Another Eero building, the Irwin Union Bank was bought by Cummins and refurbished into a conference centre, thus saving it from demolition. Similarly, another branch of the bank designed by Harry Weese was converted into a coffee shop, the second location of local Lucabe Coffee Co. in 2021. The former Republic Newspaper building by Mies van der Rohe’s disciple Myron Goldsmith, which betrays its Miesian origins with its clean geometry and glass facades, is now home to Indiana University’s architecture programme. A monument or museum the city is not, it lives.

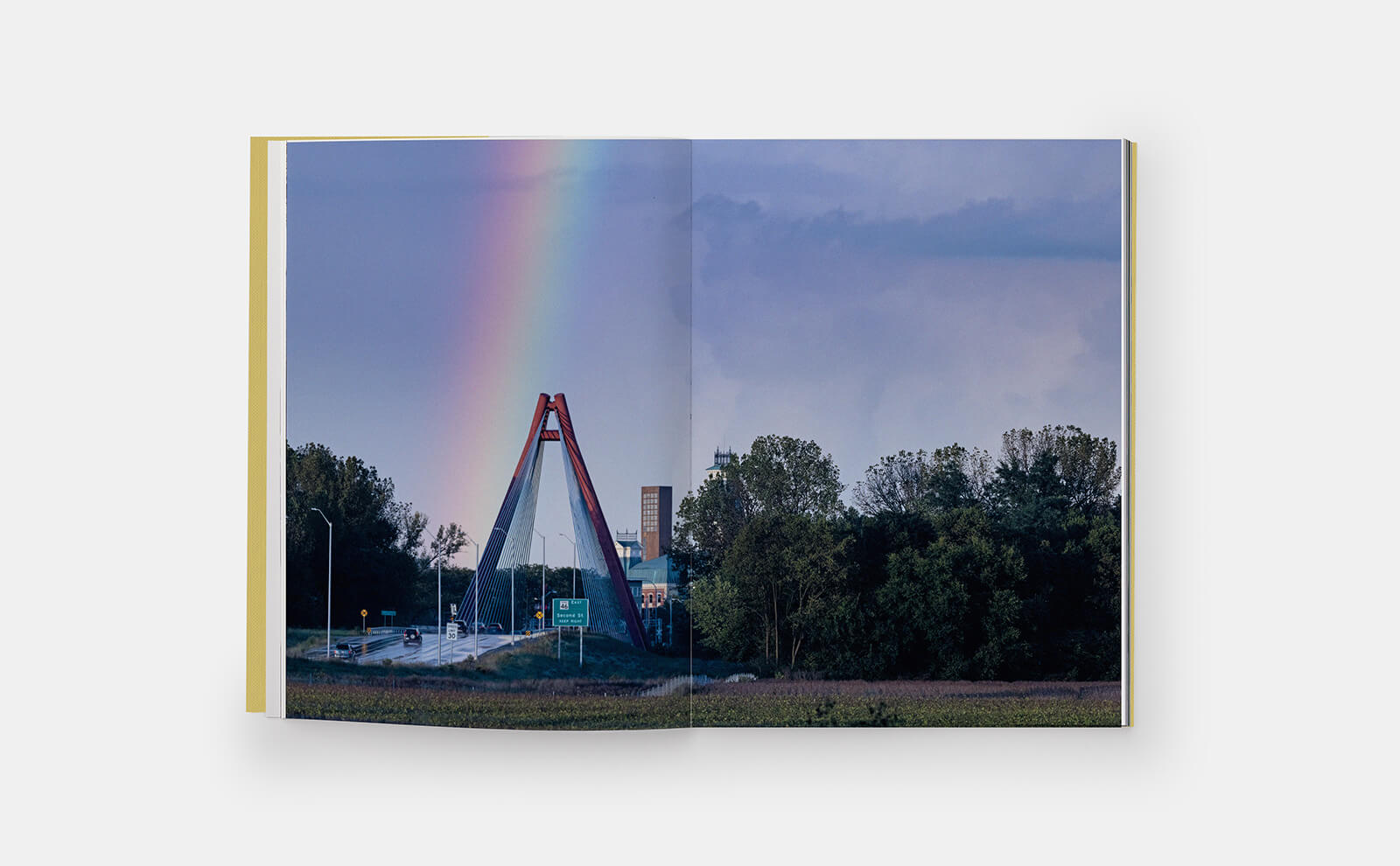

The entire town presents an interesting case for ongoing legacies and narratives of preservation for modernist architecture, which is worth further contemplation in a world where these are often demolished or left to deteriorate; products of their time stylistically or functionally. A core focus for the book then remains this stoic dialogue between the past and the present through the community’s relationship to its built environment. Images by Iwan Baan illustrate this succinctly, with drone shots placing each hero structure in dialogue with other such edifices in its vicinity, which may just be lurking in the corner of a frame, creating a carefully curated tapestry. Other photographs depict the everyday lives of the buildings, sometimes sparsely populated and sometimes teeming with life. Particularly in the street photographs, the iconic architecture seems to recede, turning into a backdrop for the typical mid-Western life centred on a sense of neighbourly friendliness. If Columbus is portrayed as a place “where you can experience good design in all aspects—including art, architecture, landscape and urban planning,” as McCoy writes in his foreword, the post-pandemic present too, in search of places of collective gathering and belonging determines the significance of Columbus’ narrative today: a unique blend of community, the American dream and the utopian hope offered and fostered by modernism.

The formalisation of a style for high modernism would be inscripted with the MoMA’s 1932 exhibition and subsequent publication of The International Style by Henry Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson. This heralded the adoption of the Enlightenment ideals for design fostered in Europe to fit the American model. It would present the idea of relentless progress through the adoption of new technology and materials, championing the image of the skyscraper. While the spirit of modernity and progress was emphasised in the desire for Columbus to be “the very best community”, its architecture was always built to relate to the human scale. Shaw states in a chapter titled Midwest Modern, “Columbus’ architecture was never really about style at all. It was about ideas and bringing the best minds to Columbus to help build a better place. Stylistic concerns over Modernism and postmodernism are very blurry in Columbus. Here, the architecture transcends fashion and has an underlying attitude about how to build. All “styles” and types of architecture were modulated here to fit the midwestern context—much like a "wholesome Mad Men"."

This concern with humaneness and a sense of tranquillity pervades the 2017 film named after and shot in Columbus directed by South Korean-American filmmaker Kogonada. Its opening sequence depicts the Miller House, a meditativeness emanating from its undisturbed interiors. The house was designed by the younger Saarinen for his friend, J Irwin Miller in 1957. The two had become close when Eero’s father Eliel was commissioned to design the First Christian Church in 1942. “First Christian is considered...one of the first modernist churches in America. In the United States. Designed by Eliel Saarinen and Christians consider...Notice how the cross and the doors and the clock are all off-centre. Saarinen's design is asymmetrical...yet remains balanced,” Kogonada’s protagonist Casey intones, trying to memorise how she will present the building to a tour group.

The church would signal the beginning of a long association of the town with Miller’s progressive taste, sense of civic pride and responsibility and hope for fostering an inclusive community through design excellence. The second modernist church design for the town by Eliel's son, Eero Saarinen—the North Christian Church (1964) — was truly radical with its octagonal plan. It’s significant that these early structures, including Weese’s design for the First Baptist Church (1965), were religious buildings, inciting a certain contradiction: that faith could be modern and progress marked by religion.

Miller’s desire to create a town where people would want to live, would result in the initiation of a philanthropic programme in the 1950s that would cover the architecture fees for the public schools that would be built in the town. Initiated by the town’s largest employer, the Cummins Foundation Architecture Program (CFAP) formalised a system wherein a school board would have to pick from a list of modernist architects provided by Miller, for the school’s construction to be funded by the programme. Eventually, they would expand their clause to include any public building to be built by a civic body.

As Shaw points out, the optimistic notion that every citizen could be lifted by institutions and a strong public-private coalition coupled with the fervour to bring about qualitative means to uplift citizens and create a better society reflected the then President Lyndon B Johnson’s hopes for the Great Society programme, drawing Columbus into the larger history of the country. After some trials, the first school to be funded by the CFAP was the Lilian C Schmitt Elementary (1957) by Harry Weese, a low-density school design with gable roofs, emphasising certain domesticity in the scheme. Subsequently, other designers would contribute to the initiative including Edward Larrabee Barnes, Paul Kennon and even Eliot Noyes.

While the roster of architects having designed the town by themselves provides an index for the history of mid-century modern architecture in the country, its progression as reflected in Columbus’ development is enumerated by Shaw in the various chapters, arranged thematically rather than chronologically. An interesting instance of this convergence between national and local narratives would be Venturi’s design for Fire Station Number 4 (1968). With a simple brick structure and Venturi’s distinct iconography, it marks a turn away from the other modernist buildings in its vicinity. It was designed around the time that Venturi published Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), a book that would come to define the beginning of postmodernist thought in architecture. Another project by Venturi, by then working with his partner, Denise Scott Brown for a highway leading into the town was never realised.

Another striking example is I.M. Pei’s redesign of Columbus’ downtown plaza, culminating in the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library (1969). It would also foreshadow the relentless redevelopment of urban centres in the late 1960s. In Columbus, this was commissioned to César Pelli, resulting in The Commons (1973-74). Described as “an indoor public park”, its glass clad form was altogether too futuristic for the humble town. The building was renovated to replace the energy-inefficient glass in 2011 by Boston-based firm Koetter Kim & Associates.

Marking a turn away from community to corporate-oriented modern architecture, the book concludes by presenting projects that were conceived in the late 2000s, showcasing an ongoing architectural legacy for the town. This section also marks a major shift in the architectural landscape, away from the typically white, male figure of the designer. All in all, if one were to draw out a map of all projects by noteworthy designers in the town, which the index at the end is very helpful in providing, one would find almost 100 projects of architectural significance, dating from 1942 to the present day. And yet, the spaces don’t lose their small town charm, poetically portrayed in the unhurried, spacious shots of the surroundings in the 2017 film.

A vital question remains unanswered in Shaw’s narrative, that he highlights: What is Columbus? Is the town to be defined by its buildings? Or in the community these fostered? 50 to 70 years after their construction, these buildings, models of an alternative utopian vision, are in need of extensive maintenance while Columbus does not have a historic preservation committee. Moreover, the fact that each building is controlled by various parties, from school boards to private businesses, further complicates things. This unique conundrum would come to imply that citizens must mobilise to figure out how to appropriately live with the past, adapting to it rather than doing away with it, as detailed before in the various examples of adaptive reuse. For, if Columbus represented the search for design excellence in service of the community in the 50s, today it stands for a similar hope, of a collective future and the conditions that might shape it.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Sep 26, 2024

What do you think?