Hata Dome by Anastasiya Dudik evokes ‘a structure unearthed rather than built’

by Bansari PaghdarJul 05, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Chahna TankPublished on : Jun 05, 2025

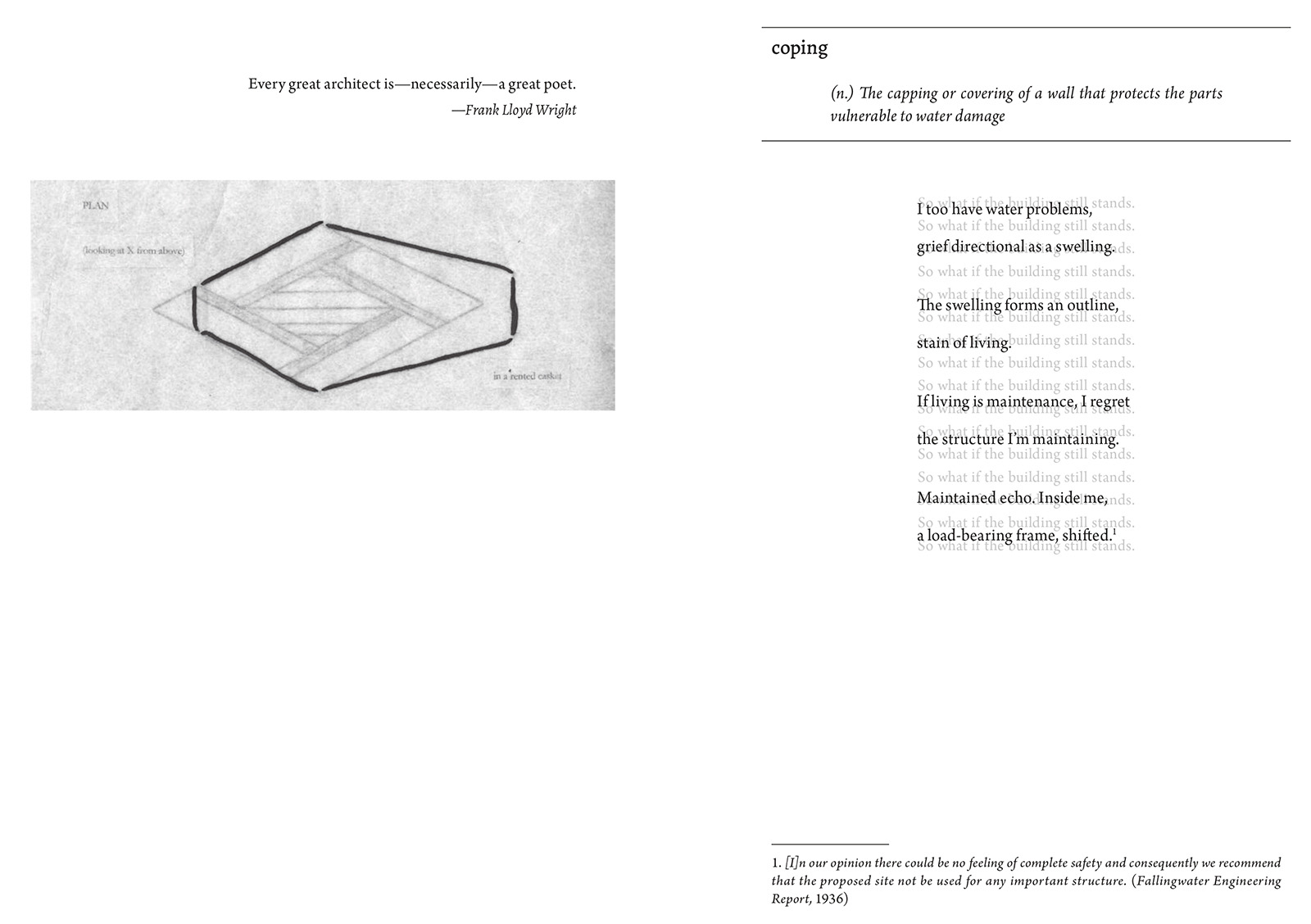

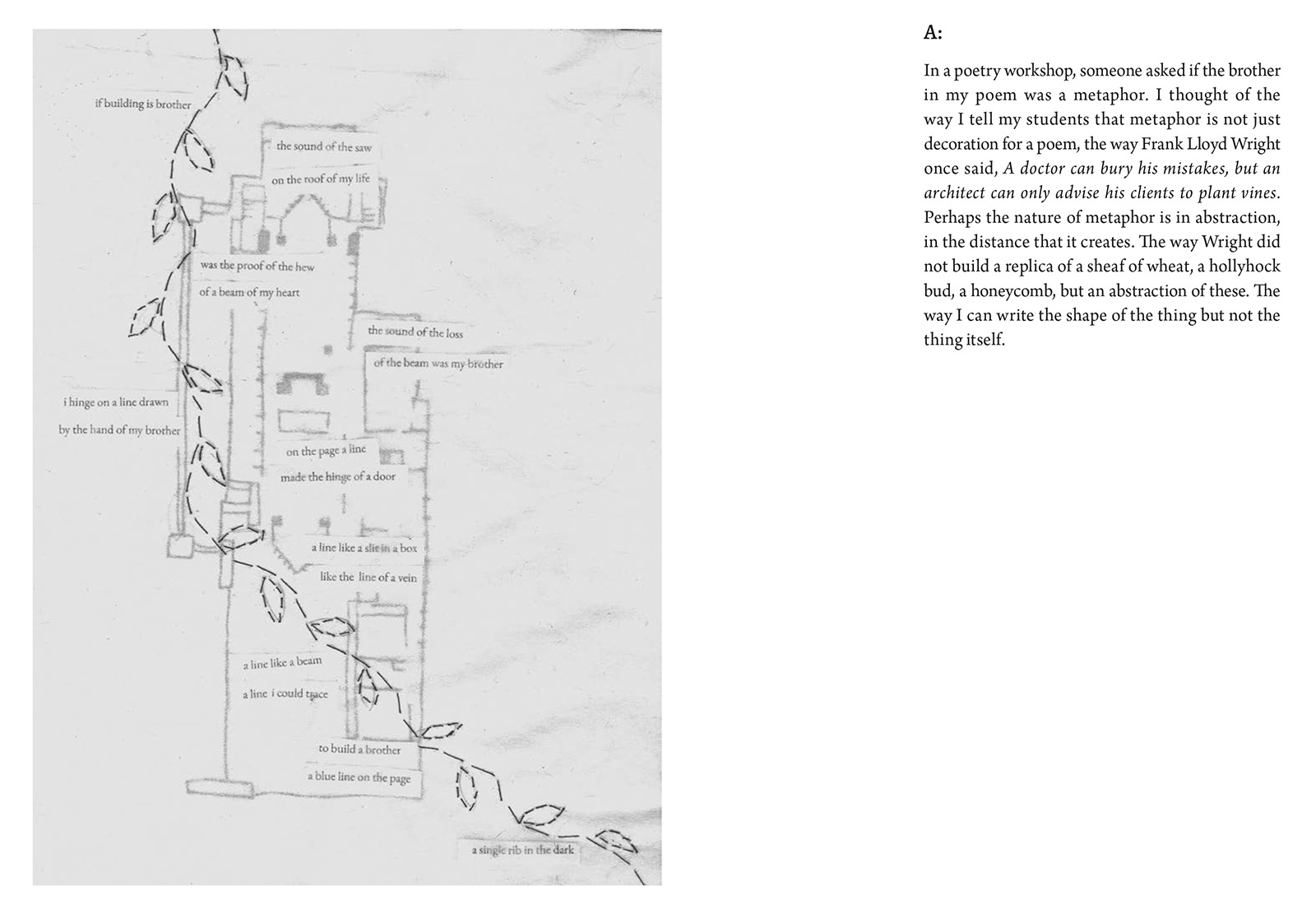

Five years after Alison Thumel lost her brother, she audited an architecture class on Frank Lloyd Wright, proclaiming she was a poet and had never built anything before. Yet, she emerged from this undertaking with Architect, a book of poems she wrote to rebuild her world around the absence of her brother. Organised into three sections—Plan, Elevation and Perspective—Thumel seeks to reproduce the exercises for her architecture class through poetry. Several poems are floor plans, guides to the complex emotions she holds onto.

Architectural drawings, course notes and allusions to the residential designs of Wright are interjected throughout the poems. Further, the book is punctuated with abstract, minimal linework created by Thumel for the class, mimicking drawings and blueprints. Through these architectural gestures, she explores how built environments mirror and absorb grief. The poems in her collection become rooms we enter, corridors we tread in and collapsed sites we visit and revisit. This echoes Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (1957), where he notes, “The house, even more than the landscape, is a ‘psychic state’ and even when reproduced as it appears from the outside, it bespeaks intimacy.” Houses are not just physical structures—they are intimate, emotional and psychological spaces that hold memory and, in Thumel’s case, grief.

Thumel begins her collection with this image of the house and the structural system that supports it. Quoting Emily Dickinson in her epigraph, she notes, “The Props assist the House/ Until the House is built.” The association between structure and poetry, houses and memory, in many ways also calls to mind poet Barbara Guest’s essay Invisible Architecture, in which she writes, “There is an invisible architecture often supporting the surface of the poem.” For Guest, this ‘architecture’ is not something to be discerned in rhyme, metre or form; rather, it follows an intuitive logic that binds a poem together, like emotional scaffolding.

Poetry, then, much like architecture, is about constructing; about supporting with its structure what it is trying to contain; about forming something out of nothing. Creating a poem is in many ways similar to creating a structure. Perhaps that is why Wright often said, “Every great architect is—necessarily—a great poet. He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.” The parallels between architecture and poetry are frequently observed by architects, likening design and construction to the writing of a poem, while buildings become the poetry of space. This idea that architecture is poetry (and poetry architecture) could be traced back to Arts and Crafts movement pioneer, John Ruskin and his treatise, The Poetry of Architecture, where he argues that the task of the architect is to appease the senses through an inherent poetics, rather than the eye with an apparent proportionality and harmony.

Thumel notes this intrinsic dialogue too, mentioning how ‘stanza’ means ‘room’ in Italian. She builds, stanza by stanza, an enclosure to situate her grief in. Through poems in Architect, Thumel not only mourns the loss but also reconstructs the mourning with the lexicon of architecture. She transliterates building elements such as the ‘coping’, ‘lintel’ or ‘sistering’ as metaphors of emotional support. The invocation of these structural elements once again echoes her sense of loss, a feeling of being adrift in the face of her profound grief. For example, sistering which involves reinforcing a damaged beam with additional material, becomes an image for the support required to hold up her own emotional infrastructure.

Apart from the reciprocative relationship between architecture and poetry that serves as a through-line for the book, Thumel situates herself in the unforgiving landscape of the prairies. She creates a cyanotype with the prairie grasses for the cover of the book. The very first poem in the book, Prairie Style, also calls attention to this, while alluding to the Prairie-style architecture Wright is most famously associated with. In his residential buildings, the vast midwestern landscape was celebrated through horizontal planes and open layouts. Wright sought to echo the natural landscape in his work, creating a language of architecture that revelled in harmony between the natural and the built. In her course notes, Thumel turns this congruous relationship on its head, using the poem to talk about the dead figure of her brother.

In Thumel’s hands, the prairies become unsettling and sinister. Her grief, like the grasslands, is an expansive landscape, horrifying. A landscape full of nothing but empty space, as far as the eye can see and where tragedy feels both inevitable and unnoticed. For years after her brother’s death, she collected news articles on those who died young in landlocked states: “...boys sucked down into grain/ silos or swept up by tornadoes are falling through/ a frozen pond. The boys I didn't know, but the landscape I did. The dread of it.” ‘Prairie Style deaths’, she calls them. She underscores the tension between Wright’s idealised vision and the brutal, indifferent reality of the land in her text. Thumel is constantly drawn to Wright’s figure, not only because of the class she audits. He serves as the book’s architectural spine, a recurring motif, a ghost haunting the white spaces of the spreads.

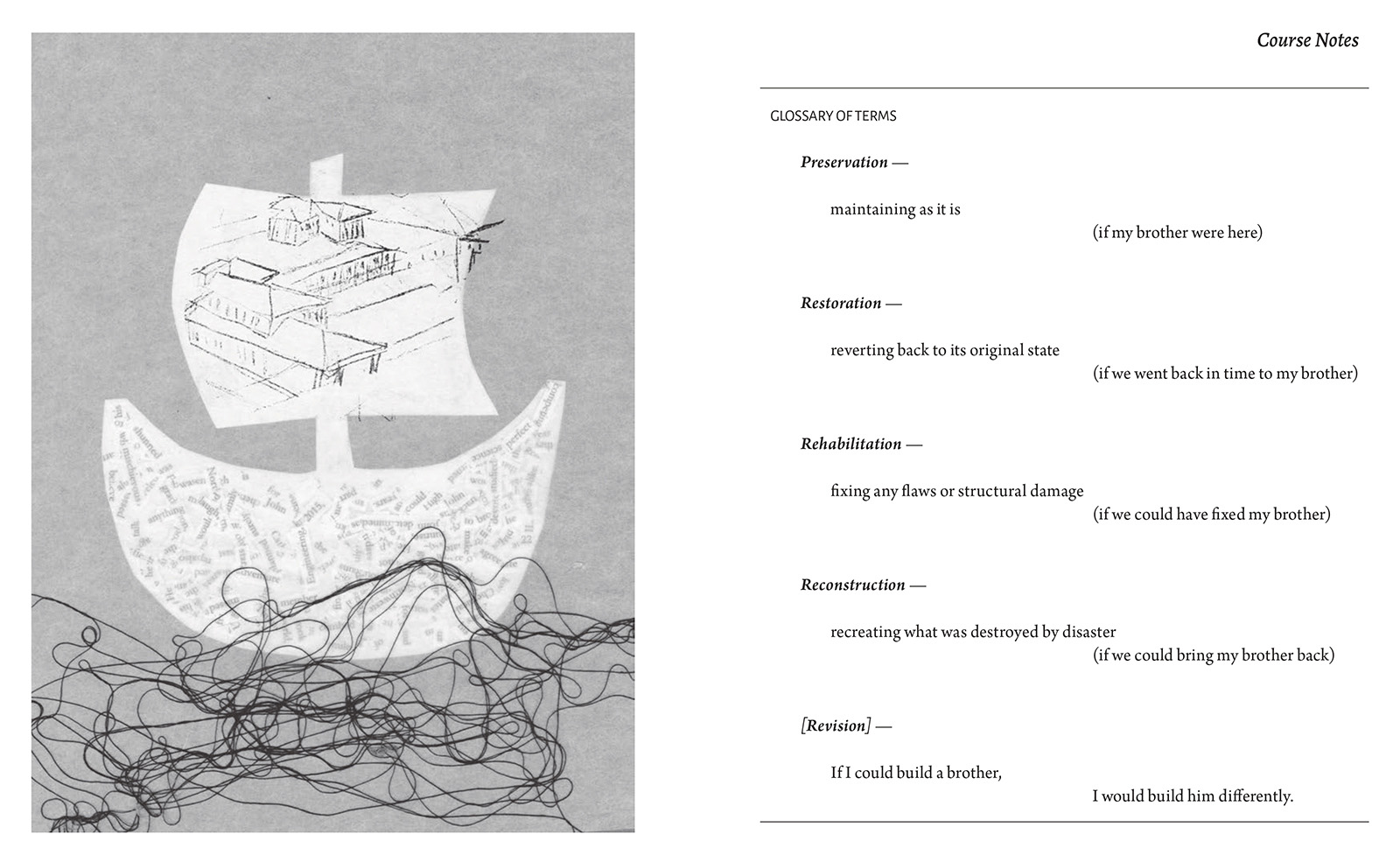

She weaves poems around Wright’s buildings—often flawed, torn down and rebuilt—drawing a parallel between that architectural imperfection and the fragility of her attempts to rebuild meaning after her brother’s death. While she writes about projects such as the Robie House, Usonian Home and Fallingwater, she however returns time and again to Taliesin. Perhaps no house in architectural history has been more tragic. Originally built for Wright and his mistress, Martha (Mamah) Borthwick Cheney, Taliesin was destroyed twice—first in 1914, when a fire broke out and Cheney and her children were murdered, and then by another fire in 1925. Every time Wright rebuilt Taliesin, he changed it a little, never having created a blueprint for it. The house becomes a mythical object for her—a palimpsest of ruin and rebirth; but it also becomes a mirror to her mourning process—repetitive, obsessive and never identical.

Was Wright’s act of rebuilding a channel for his grief? What memories of the previous structures do renovated buildings hold? Is preservation in architecture itself a way to hold on to a semblance of order? Was Wright’s rebuilding an act of preserving the essence of Taliesin, or constructing it anew? In this sense, we could also think of Taliesin as embodying the paradox of the Ship of Theseus. The paradox, originating from Theseus, a hero from Greek mythology, asks if all the components of an object—components that make the object what it is—are replaced one by one, does the object still remain fundamentally the same? Thumel writes, “Philosophers talk about/ the Ship of Theseus, its planks replaced one by/ one. Architects call this preservation. Poets call/ this revision.” Her proposed ‘solutions’ to the paradox are yet another means through which she tries to make sense of her grief, attempting to understand how we may preserve what has been changed.

Architect is about absences as much as it is about grief—how Thumel’s grief stems from the absence of her brother; how the absence of a thing defines what is left behind; how, in the absence of a thing, you learn to re-discover the thing itself, albeit transformed. The book's cover itself traces the absence of the grasses from the prairies on paper. If the poet’s brother has died, does it mean he is really gone? If the brother’s absence is filled with memories of him, does it mean he is still here? Is it possible to resurrect him from the dead? If a ship’s parts are replaced, does it remain the same ship?

Through the book, Thumel constructs a poetic landscape that operates as both elegy and edifice—a collection that mourns personal loss while reframing grief as a kind of architecture. Early in the book, she writes, “When he died, my brother became the architect of the rest of my life. Grief became the house in which I live.” Like poetry, architecture is simply a vessel in which we contain memories. And, our memories are houses that we haunt and that haunt us in return.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Chahna Tank | Published on : Jun 05, 2025

What do you think?