‘Architecture After War’ posits a guide for post-war reconstruction in Ukraine

by Almas SadiqueApr 18, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Almas SadiquePublished on : Nov 10, 2023

Various anthropological findings hint at an ancient society where men and women were at par with each other, with neither gender dominating the other. While the veracity of this finding is contested, one can arguably surmise that the nomadic tribes of the ancient past must have had little chance to establish gender roles and ascribe authority while hurtling from one location to the other in search of food and shelter. It is easier to ascribe the emergence of such segregation to a later period, perhaps when the earliest residences were built, civilisations were established, and the need for administrative bodies emerged. While these theories can endlessly be debated and refuted amongst archaeologists, anthropologists and historians, it is worthy to note that most of modern history bears disproportionate cognizance of the male population, with little mention of women’s contributions to innovations and inventions.

One can, again, arguably, cite this phenomenon to the practice of segmenting work (both in the domestic and public spheres), segregating workers (again, both within and without the household) and levying inequitable value to labour (in tandem with the profit generated). This system finds encouragement and enhancement under the helm of capitalism. Another aspect that has managed to destabilise the harmony of societies by levying disproportionate power to the male populace, is western colonialism. Various indigenous groups refute the common belief that sexism has pervaded societies since its inception. Despite performing different roles, labour carried out by both men and women was valued, and held at par, in such cultures.

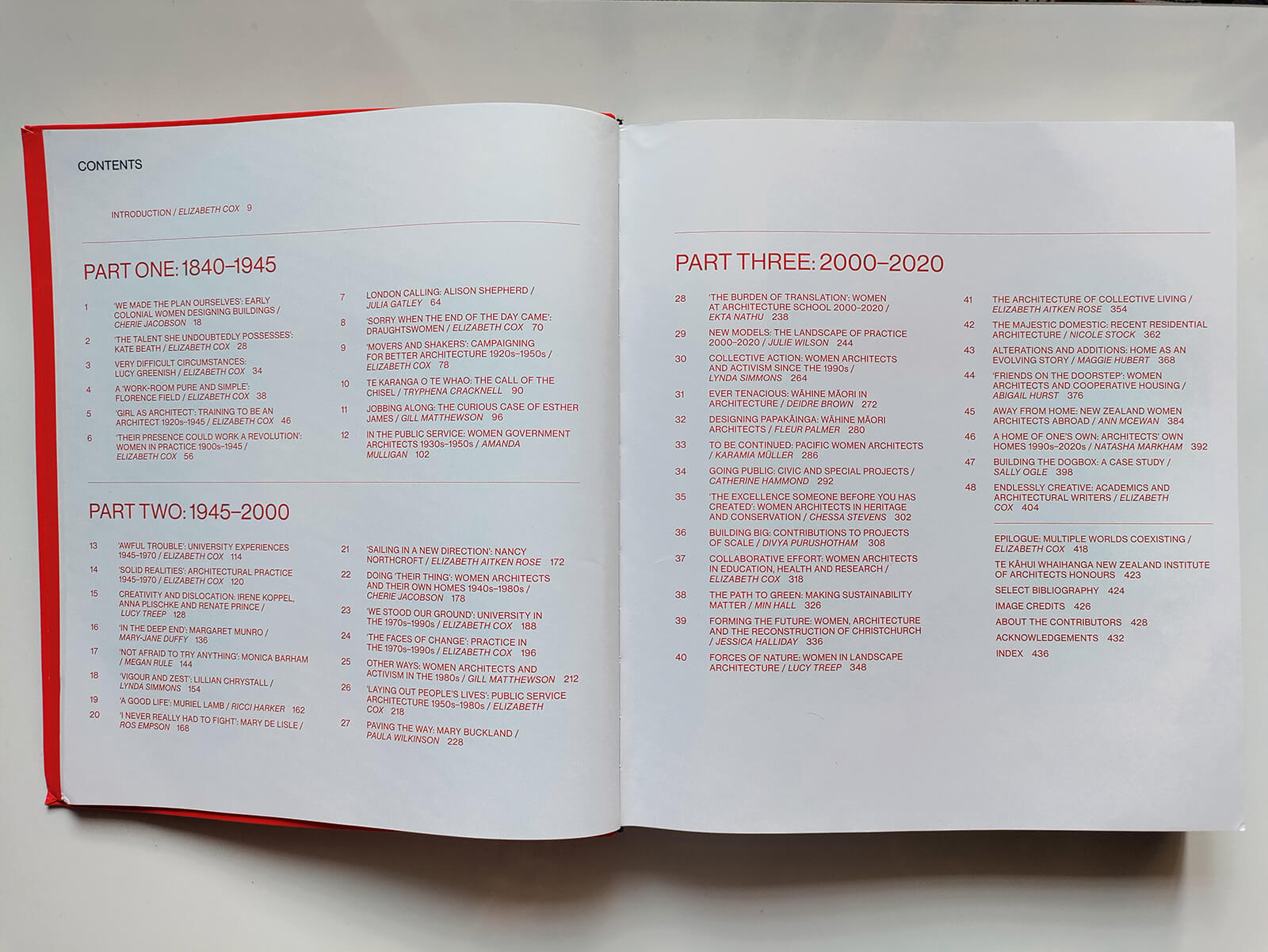

With the all-pervasive role of capitalism in extant societies and the understanding that more than 80 per cent of the globe has been colonised by Europeans in the past five to six centuries, it is imperative to address and counter sexism and racism, even if it only serves as the treatment to the symptom and not the cause. A recent project, a book, that does a tremendous job in documenting the contributions of women both from among European settlers in Aotearoa New Zealand as well as those of ethnic groups, such as Māori, Asian and Pacific people, is Making Space. Edited by Wellington-based historian Elizabeth Cox, Making Space comprises 48 essays that delineate the presence of women in the architectural sphere and associated industries from 1840 to 2020. The book also ponders upon both individual and collective struggles faced and strategies employed to make the profession more inclusive.

Cox mentions in the introduction of the book, “Making Space seemed an apt title for a book that chronicles women making physical spaces, buildings and landscapes, while also making space within the profession for themselves and for those who followed them. As the work progressed and other writers became involved, it became clear that the book itself was a space in which women could write about architecture, their own work or that of their peers and predecessors. Just as architecture pushes people into working collaboratively, so too has this project. The 29 other women who have written chapters are architects, architectural historians, academics, students and other practitioners, and all of them were courageous in their examination of the profession.” The collation of these contributions, narrated by women who themselves are trudging forward in all spheres of the architectural profession, serves as an antithesis to the assumption that women have had no presence in the field.

The book not only details the contributions of women who were formally registered for the role or ones who had the opportunity to hold positions in architectural firms or establish studios but also talks about those who held no relevant degrees or experience in the field but were responsible for designing structures off their own accord. When exploring, understanding and presenting a niche subject, one witnesses several firsts. Making Space, which details both the pedagogical and professional contributions of women in architecture, too, delineates the stories and circumstances of various firsts. Some of these include Lucy Greenish, the first woman in New Zealand to register as an architect in 1914 and open a sole architecture practice in 1927; Kate Beath, the first professionally qualified woman architect via the articles system; and Merle Greenwood, the first to graduate with a bachelor of architecture from New Zealand University and first to work in New Zealand's public service as an architect. Alison Shepherd, who completed her education from Architectural Association in London and passed the RIBA exams, was the first woman to gain such qualifications in New Zealand, and Mary Lysaght was the first woman in the country to qualify as a landscape architect. Lillian Chrystall earned many firsts during her life. She was the first female architect to win a national-level award for a building in New Zealand (Chrystall was awarded the NZIA Bronze Medal for the Yock House in Auckland). She was also the first female studio tutor at Auckland University College School of Architecture in 1948. Additionally, she was the first woman on the Auckland Savings Bank Board of Trustees in 1975 and the first female chair of the ASB board in 1983. Deidre Brown, who also authored a chapter on the contribution of wāhine Māori to architecture, in the book, is the first indigenous woman in the world to hold the position of head of school at the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of Auckland. Tere Insley, on the other hand, is the first wahine Māori to receive a degree in architecture and register as an architect in Aotearoa.

The book is divided into three parts, based on the periods covered. The first section of the book delineates stalwarts working in the field from 1840 to 1945. It focuses on the pioneers of the profession such as Lucy Greenish and Kate Beath. A chapter within this section details the stories of Marianne Reay and cousins Mary and Ellen Taylor, both of whom were not qualified architects, but who designed the St John’s Anglican Church in Wakefield and a drapery shop-cum-house on Cuba Street in Wellington, respectively. This portion also illustrates the careers of women architects who trained in the earliest forms of architectural education and went on to work across both private practices and government departments. Across the various examples strewn across the pages of this initial section, one can trace a pattern of elite connections and monetary surplus paving the way for womenfolk to enter spaces otherwise deemed inaccessible for them. The architectural field was still heavily gatekept for women from working-class families during this time.

Through the example of Florence Field, who designed a labour-saving kitchen in the early 1920s, one can also derive an understanding of the juncture that helped invite more women into architecture and architecture-adjacent fields. Various liberal advocates in higher positions deemed that women knew better about the layout of houses, home decoration and interior beautification. This paved the way for the influx of various women into architectural offices. Most of them, however, were not architects. They worked as draughtswomen and fulfilled other administrative roles (some of which also required them to engage in ancillary architectural work). The reason behind the integration of more draughtswomen as compared to architects can be attributed to the difficulties posed in registering, taking exams, and opting for unpaid apprenticeships in order to formalise one's position as an architect. Some prominent draughtwomen from this period include Miss M A Mclntyre, Dorothy Harman and Thelma Williamson. Some other roles that absorbed women in the 20th century were New Zealand public service jobs within the Ministry of Works, as well as research work accorded by the National Council of Women after the First World War.

Additionally, a chapter in this section, authored by Tryphena Cracknell, discusses the contributions of Māori and Pākehā women in the realm of carving and casting spaces, as well as advocating for better designed facilities for both homes and urban spaces. “For some, these stories may be extraordinary, while for many women carving is simply a fact. Women have carved, women carve. This is not to argue that there was not customarily a gender division in the world of carving, but it was likely to have been much more fluid than post-colonial male-dominated social acknowledgement has dictated. It is demonstrated in the instances of wāhine trained in the art of the taiaha, or whaikōrero, or the wāhine toa who wield a chisel with artistic talent and confidence,” reads an excerpt from Cracknell’s essay in the book.

The second section of the book, covering the years 1945 to 2000, discusses the experiences of women in both universities as well as on the field. It delineates the issues that thwarted the growth of the female populace in the field. Some of the reasons highlighted include the substandard behaviour of the authorities and students with women in universities, difficulties posed in registering as an architect, prejudice faced at work, withholding promotions for women, and the child-bearing and rearing responsibilities limiting professional growth and sustenance. Although, the number of women architectural graduates remarkably increased towards the end of the 20th century, this growth did not proportionately reflect in the female workforce. Cox notes that the number of registered women architects was five in the years from 1966 to 1975, 42 in the subsequent decade, and 81 in the years ranging from 1986 to 1995. While this period normalised the presence of women in both small and large architectural firms, a negligible proportion would rise up the management ladder.

Several chapters within this section delineate the stories of women who were able to cast a presence in the industry by establishing firms by themselves or with their partners. These examples drive home the point that societal norms were visibly changing, with lesser familial restrictions. Some women who had thriving careers during this period include Margaret Munro, Monica Barham, Lillian Chrystall, Muriel Lamb, Mary De Lisle, and Nancy Northcroft, amongst others. Various women such as Helen Sim, Ros Empson, Sue Clark, Tere Insley, Diane Brand, Valerie Morris, Shirley Penfold, Rosemary Eagles and more worked in public service departments. It is believed to have been easier for women working in this arena to get registered as an architect, as compared to their counterparts in the private sector.

The 1980s also witnessed the founding of the Women’s Institute of Architecture, an organisation which curated seminars meant for both education and networking; addressed higher-ups in the educational sector with the issue of the lack of female staff in universities; and set up a sub-group in order to encourage high school girls to study architecture. Apart from the efforts of the Women’s Institute of Architecture, the Public Service Association in the country also got involved in a battle for legislation to ensure pay parity for women.

The third and last section of Making Space covers the years 2000 to 2020. Despite focusing on the least number of years, this portion comprises the maximum number of essays, hinting at both, the increased involvement of women across disparate sub-arenas within the field, as well as the increased documentation pertaining to this topic. It highlights the works of academics and architectural writers, New Zealand women thriving abroad, efforts by women architects in the realm of civic projects, heritage and conservation, educational architecture, research and pedagogy, landscape architecture and other disparate sub-disciplines. Lynda Simmons, in her essay, talks about the establishment of Architecture + Women New Zealand, an organisation that regularly hosts events and symposiums meant to educate, connect and support marginalised communities. They host a self-uploading database for all women architects in the country to update their details, hence serving as a medium for documentation. They also provide educational and guidance-based resources for architectural enthusiasts, students and professionals. On the other hand, indigenous activism in the region has led to the formation of Ngā Aho Māori Design Professionals, which centers on educating people about Māori issues and finding solutions to them, mainly in the realm of the built environment.

The essays in this part present the image of a changed architectural landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand, wherein the case for women architects no longer needs to be made with the same exertion, and conversations can move forward to include and address constraints within pedagogy—in tending to the experiences of marginalised communities. While Ekta Nathu’s essay talks about the burden of translation that marginalised communities bear in Eurocentric institutions, Fleur Palmer talks about the relentless subjugation writ by the colonial system upon the indigenous lands, the impact on the self-determination, autonomy and status of Māori tribes, as well as the spatial exclusion of Māori, and particularly Māori women. She also highlights the need to fight for the return of ancestral land. Palmer explains, “The Crown’s aim was to disempower Māori tribes by either stealing and assuming outright ownership of land, or partitioning land through the Māori Land Court. Partitioned land enforced a dispersed settlement pattern, It also imposed a patriarchal system in which shares were allocated mainly to men, not women, thereby destroying the mana (status) that Māori women traditionally held. Surveying and breaking land up into individual parcels encouraged the coercive acquisition of blocks of land by the Crown so land could be allocated to settlers.”

Deidre Brown, in her essay, correspondingly asserts, “The most effective way to decolonise Aotearoa New Zealand’s built environment is to change the way architecture is taught in the country’s tertiary institutions.” She brings to focus the contributions of various wāhine Māori, such as Fleur Palmer, Tere Insley, Jade Kake, Elisapeta Heta, Samantha McGavock, Kirsten Spooner, and Hana Scott, amongst others. One of the attempts highlighted in the chapter is wāhine Māori community’s engagement in protecting their built heritage, as visible in the involvement of architect, artist and educator Keri Whaitiri in Christchurch's recovery plan after its devastation in the 2011 earthquake.

The book manages to trace the thriving evolution of women's participation in the field of architecture. With testimonies and analyses from Māori women, the book brings forth the (pressing) contemporary issue of unbalanced and inequitable circumstances experienced by the population indigenous to the land of Aotearoa, establishing, hence, the urgent need to not only humanise their struggle but also the necessity for radical changes in favour of all the natives.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Almas Sadique | Published on : Nov 10, 2023

What do you think?