Anton Repponen on distorting the mundane into unfamiliar visual explorations

by Zohra KhanJul 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Zohra KhanPublished on : Dec 07, 2023

"If you abandon problem-solving completely and go about focusing on problem-making then you lose the essence of the designer as someone who acts in the world.”

– Silvio Lorusso

It was the first day of architecture school when the professor asked a crowd of luminous young fresh-out-of-school faces to pull out their crisp white sheets and start doing what would be a pain-of-an-exercise in hatching. There was a rush in the air. As I hastily pinned my sheet to the drawing board in front of me and scrambled to unroll the alienating variety of pencils that we were asked to get, I began drawing six large rectangles on the sheet, each had to be manually hatched by a different kind of a pencil grade. Line after line, in laborious strokes and the absence of a rationale, the purpose of why we did it eludes me to this day. Maybe this was one drop in the ocean of my feelings of alienation in the five years of architecture school.

Why I shared this memory here is to point towards the delusion that engulfs practitioners and students as they navigate the realities of the creative disciplines, particularly architecture and design. A new book released by Set Margins press, titled What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Delusion by Lisbon-based designer and writer Silvio Lorusso expresses the broken nature of design, gives a platform to represent the frustrations of designers and creatives, and elaborates on why good design is about inhabiting chaos.

A little something from the book's preface reads, "What was once a promising field rooted in problem-solving has become a problem in itself. The skill set of designers appears shaky and insubstantial – their expertise is received with indifference, their know-how is trivialised by online services. […] If you see yourself as a designer without qualities; if you feel cheated, disappointed or betrayed by design, this book is for you.”

I connected with Lorusso over a video call to discover more about the book. The following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Zohra Khan: Could you give us a peek into your creative practice?

Silvio Lorusso: I am a writer, artist, and designer based in Lisbon, Portugal. I am also a tutor at the Design Academy Eindhoven in The Netherlands. I have my own practice as a media artist mostly. I have been trained as a graphic designer, where my interests gravitated towards new media. These days I am mostly busy writing, doing design theory and criticism in the written form. So I have stopped being a designer somehow.

Zohra: What inspired you to write the book What Design Can’t Do?

Silvio: Well, this is my second book. I wrote another book on entrepreneurship and precarity called Entreprecariat. This book I felt, was a necessity because in my context I felt there was a seeming dark side of design culture that wasn't represented somehow by the so-called discourse. There has been a manifestation of frustration by many designers and students. I thought it would be good and somehow important to represent those feelings in a publication. To take them seriously perhaps because normally they are dismissed; there are rants and pessimism, but these things don’t find a platform in design conferences, and books, even. I thought that it would be important to at least acknowledge it. Slowly while putting it all together I realised that this could be a lens to look into the history of design itself and the contradictions of a designer. The book became a historical investigation into forms of disillusion. I started the book with a sociologist who speaks in the fifties to a crowd of designers and says, “I understand your frustration”. You start to discover that there is a long trajectory, that there is something which is fundamentally the disillusion of modernity, and there’s a kind of tension between being someone in control of things and being controlled by a larger system. This is the main paradox of designers nowadays, and also in the past to a certain extent.

My book is a small counterbalance to the excessive positivity of the discourse. – Silvio Lorusso

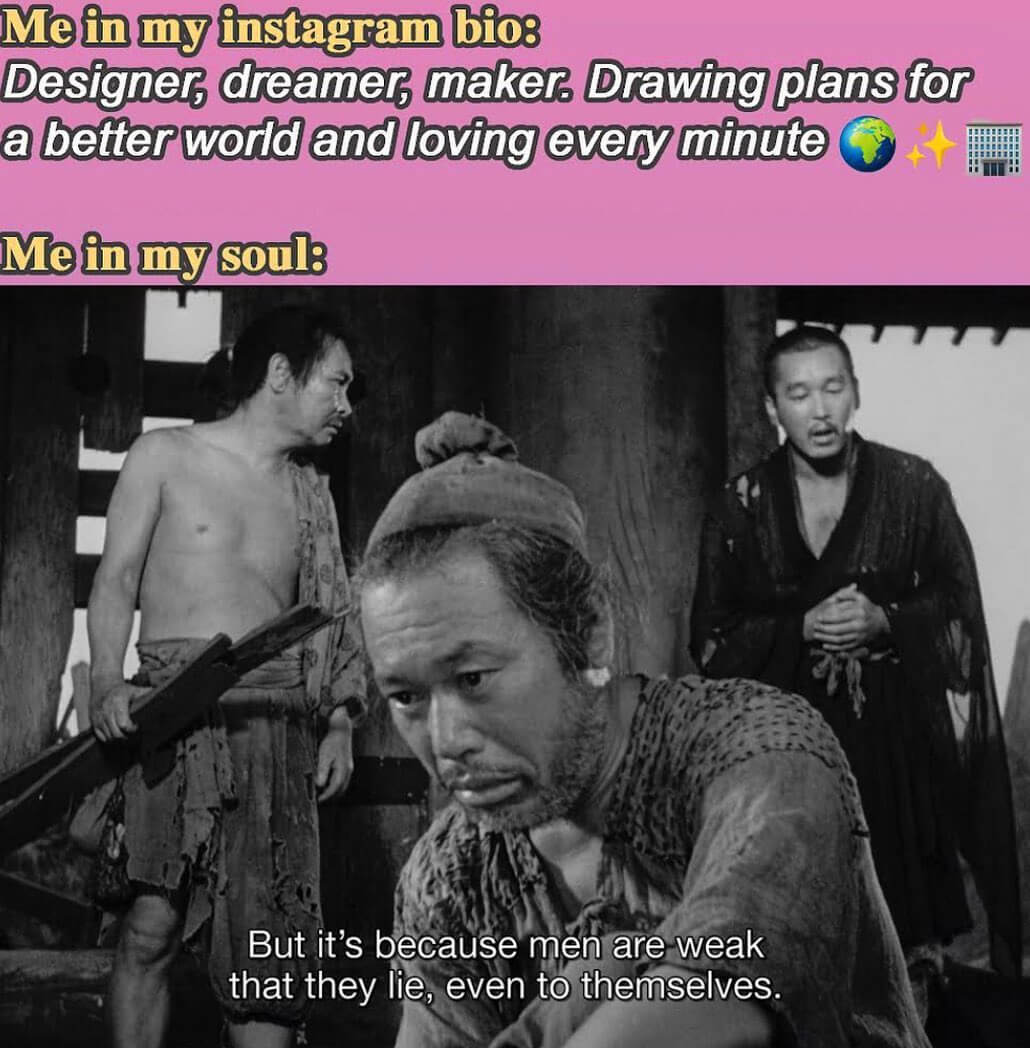

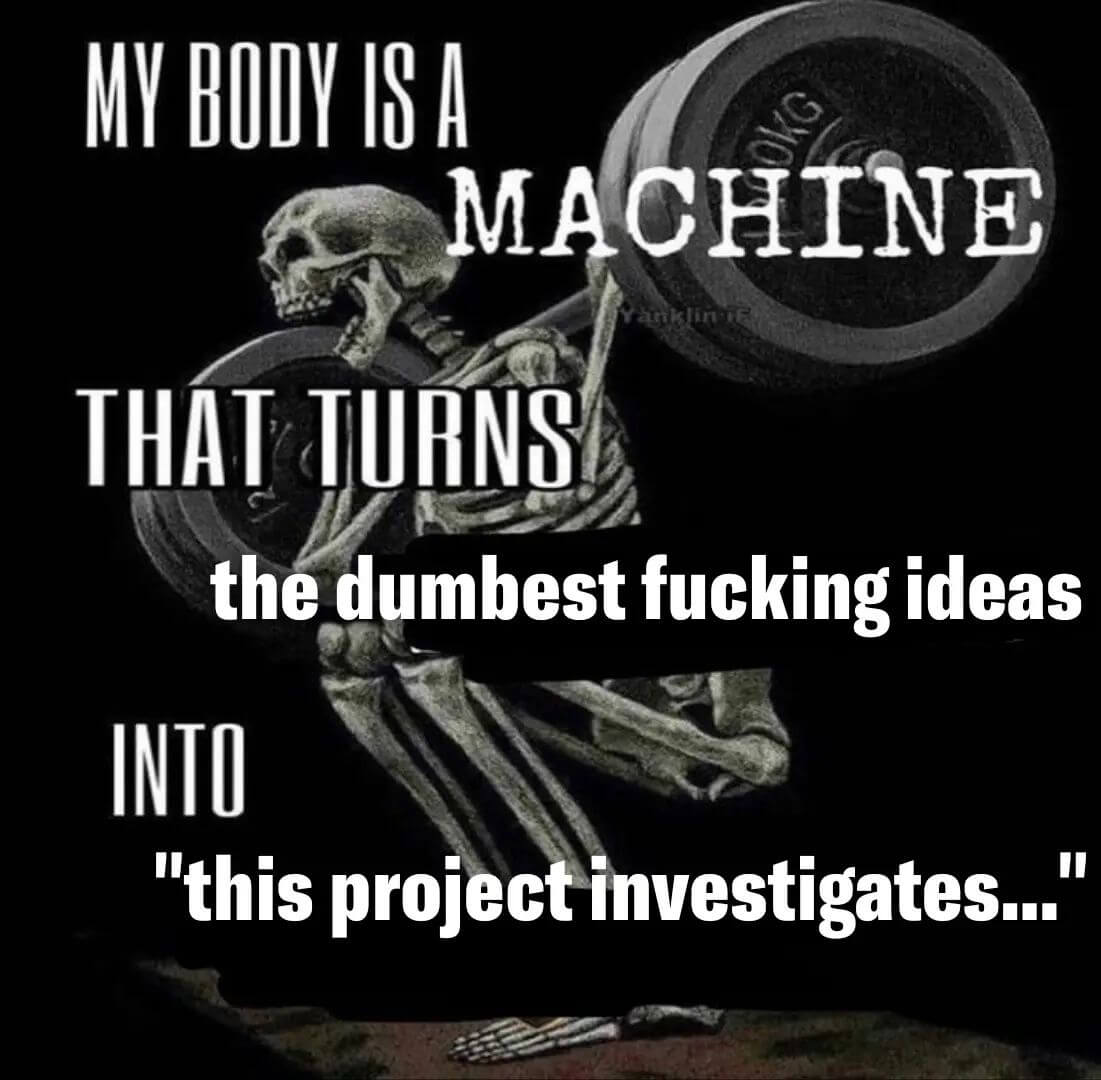

Zohra: A personal observation of mine while I was reading the book is in one of the first few chapters. There were graphics that read, ‘Design Ruined My Life’, and another that said, ‘Graphic design is shit. Coding is shit. All I want is revenge.’ It feels there's a certain angst that has been flowing throughout the narrative. Could you talk about that.

Silvio: It's important to specify that this angst is manifested hyperbolically into the memes. One thing has to be the balance to the medium itself. Of course, a medium like a meme normally will be hyperbolic, excessive; that's how meme works. My inclusion of certain hyperbolic stances, like these ones, was like a groundwork to collect that feeling. I think these things should be taken seriously, which are not mine personally, should also be taken not literally. If it's an exaggeration to say that design ruined my life, that sentiment is there in a more subtle way.

When it comes to me, I never had that angst in such an explosive way. I like to think that the book is dispassionate in a sense that the style of the book is not too ranty or explosive. I mean this depends on readers and how they judge it. The main point throughout the book is that passions matter. This is a shift from the traditional idea of western design in which you try to think beyond what you feel, and that it's often about rationality and the mind.

My attempt was to show somehow that passions, even the so-called sad passions, take a part in the shaping of what design is, what design can do or not. Beyond my focus on the sad passions, I believe design is fuelled by extra optimist, extra positive ones. For example, enthusiasm is the fuel of design conferences, design culture, and design pride. My book is a small counterbalance to excessive positivity of the discourse. It’s a little attempt to balance it. When you look at the book, by itself it might seem very negative, very explosive in its statements, but when you compare it to the whole ecosystem of design publication, well, it's a small drop in the ocean of optimism.

Life happens, and it's up to us as design creatives to be able to decide what we include in what we call design.

Zohra: There's a statement in the book that says, ‘The book you are reading locates itself within chaos. As such, it’s a weird design book. It explores the disorder that can’t be contained, the mess that overflows the dams of what we consider arranged and designed, including our mental models and subjectivities.’ As creatives, what has been embedded in our frozen conscience is the notion that clear thinking largely delivers good design. On the contrary, your stance observes that good design is about inhabiting chaos.

Silvio: That part on chaos opens the book and the starting point is the realisation that order, simplicity, and clarity have been functional illusions of design since modernism. These illusions have been useful to place design on the map, but the very clear feeling that we have nowadays—not only within design but within society at large—is that chaos prevails, both on the societal level, as well as on the scale of individual lives.

The radical point of the statement of the book is to say that chaos cannot somehow be ignored because otherwise, it creates a larger detachment between this promise of order which is the promise of design, and a reality of messiness, and lack of control. Life happens, and it's up to us as design creatives to be able to decide what we include in what we call design. When you do this, the idea of design changes completely. Design is normally thought to exist in a vacuum, but when you start thinking like this, you have to acknowledge the fact that design actually is a pre-existing reality that you struggle with, and therefore, design becomes a bricolage. I really like a quote by the legendary Italian designer Enzo Mari, which goes something like this: “Design is like looking in the fridge. You find eggs and yogurt, and you have to come up with a recipe.” That’s a splendid idea of what design is in real life. So I also wanted to inject, with this book, the idea of an everyday life of a designer, which somehow has not been very present in the discussion. Like, how do they live now? What the environment looks like, and how that shapes their own feelings and beliefs.

Zohra: How were you as a design student? Were there any significant challenges that you faced in school which have been channelled as key observations within the book?

Silvio: I have always been an awkward design student, in the sense that I always had a foot in other fields. So, for example, while I was studying industrial design, I was doing music videos. While I did graphic design, I was looking into coding. In a way, I always tried to escape the disciplinary boundaries. As a student, I was always drawn to writing. One of my formative experiences was when I did my masters in graphic communication, I was also one of the people running the school blog. I was writing very critically, and was very active in creating a discourse around the school, and writing things that I am very ashamed of. This was my early twenties.

For me, it was always important to somehow use the medium of writing to reflect on what design is. There was another thing: my path has been about closing the circle that talks about my feelings about design, because when I was a student, like many other students, I was against a normative idea of design. I was against modernism. I always felt that we have to open up, and that we shouldn't just provide solutions, but also question the very problems. I still believe in that. But I also faced a reality in which I realised that that kind of stance, which in the book I described as a cultural professionalism, is more of a necessity than a virtue of the critical designer. It is really a necessity. Many architects now struggle to find even access to solving problems in the sense that they cannot build. There is nothing like an entry point. So, what do you do if you can't work on that scale?

You work on a small scale, which is a critical scale, a cultural scale. I still like that cultural approach, but I now see it in a bigger context of labour condition and massification of the design product. But of course, I am speaking of Europe and the United States. I don't know if that’s the case for the rest of the world.

The issue of considering design as problem solving is a contested ground.

Zohra: Would you say design, in its essence, is problem-solving?

Silvio: The issue of considering design as problem solving is a contested ground. When I was a student, I was introduced to the idea of the designer as an engineer who, if given a problem, interprets it and offers a solution. That more or less has been the standard, but clearly in design culture, the very notion of a problem has been questioned. The fundamental question has become, 'What is a problem and how do you locate how big you consider it?' Much of the work, for example, of Victor Papanek has been really about answering this question. He had huge diagrams in which, to define a problem, he would speak about sociology, activism, politics, and so the problem would expand.

Another notion is that there are some problems, for example, homelessness, that are not technical problems, so they cannot be truly solved in a technical way. They are full of ambiguities, and they will always be politically charged, so there is no one solution. These are like the notional, wicked problems that are always connected to societal values. It’s not like solving a mathematical equation.

This awareness of the problem of problem solving, the fact that it is something societally driven and is not neutral has entered the design discourse, in Europe at least. So now the balance has been completed to the other side in what I would define schools that are quite advanced in their thinking. But this kind of advancement trickles down to design culture as a whole. And as a result, you have almost a snobbish dismissal of problem solving. If I tell you in the context of the avant-garde school that designers are problem solvers, I am putting in a category that is lower, because they don't question the very idea from where the problems come from.

My proposal is somehow to bring back this notion of problem solving. If problems are wicked and not neutral, it doesn't mean that you don't try to solve them anyway. The point is that problem solving as a form of approaching design is a humble yet provisional way to do design. The risk is that if you abandon problem solving completely and go about focusing on problem making then you lose the essence of the designer as someone who acts in the world. Nowadays, we have increasingly growing category of educational designers who interpret the world. They reflect on the world instead of acting in it. Very often they don't even have the instrument to do that reflection in a convincing and deep way. So that's why I am skeptical of notions like design research and art research. That's the criticism that I bring with the book but it's quite specific to a certain context. And to be frank, I don't know how it will be read outside of this context. But I think in more technical environments, certain signs will be recognised.

Zohra: What is NEXT for you?

Silvio: I have an idea in mind, but I want to begin by taking a long thinking break.

by Asmita Singh Oct 04, 2025

Showcased during the London Design Festival 2025, the UnBroken group show rethought consumption through tenacious, inventive acts of repair and material transformation.

by Gautam Bhatia Oct 03, 2025

Indian architect Gautam Bhatia pens an unsettling premise for his upcoming exhibition, revealing a fractured tangibility where the violence of function meets the beauty of form.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 02, 2025

Gordon & MacPhail reveals the Artistry in Oak decanter design by American architect Jeanne Gang as a spiralling celebration of artistry, craft and care.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 02, 2025

This year’s edition of the annual design exhibition by Copenhagen Design Agency, on view at The Lab, Copenhagen, is curated by Pil Bredahl and explores natural systems and geometry.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Zohra Khan | Published on : Dec 07, 2023

What do you think?