Transgenerational wisdom: The story of the Suh family

by Lee DaehyungSep 22, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Lee DaehyungPublished on : Apr 21, 2025

In an age saturated by curated feeds and algorithmic selves, the human body risks becoming a mere interface—edited, optimised, disembodied. But Ron Mueck’s sculptures, now quietly pulsing within the halls of Seoul’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA Seoul), insist otherwise. Mueck, born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1958 and based in the United Kingdom since 1986, has developed a sculptural language that draws on close observation and interior resonance rather than theatrical gesture. His figures do not shout. They return us to the body not as spectacle, but as vessel—for memory, for silence, for the tender strangeness of simply existing.

This return feels especially urgent in Seoul, a city at the forefront of digital acceleration, artificial intelligence and algorithmic culture. In a nation where superintelligent systems are beginning to challenge the very definition of what it means to be human, Mueck’s sculptures slow us down. They ask us not to decode data but to dwell in presence—not to perform identity but to feel its texture. In a time when so much of life is shaped by information, this exhibition reminds us of the primacy of embodiment.

This exhibition—the largest survey of Mueck’s work in Asia to date—gathers 24 sculptures shaped across three decades. But the show does not proceed chronologically. It unfolds like breath, like the slow dilation of a pupil adjusting to the dark. From the moment one enters, it becomes clear: Mueck is not sculpting likeness, but carving toward a deeper interior. His figures—rendered in silicone, fiberglass, resin and painstakingly applied human hair—stand at the threshold between being and becoming. They are still, yet far from static. They hum with a different kind of life: the residue of touch, the echo of private thought, the tremor of emotions too subtle to name. Mueck’s realism is not anatomical but existential. Beneath every surface lies a pulse—of grief, of wonder, of time made visible through skin.

Two works that exemplify this emotional architecture through opposing manipulations of scale are Ghost (1998) and Young Couple (2013). The former portrays a teenage girl, unnaturally large, withdrawn into herself. Her arms fold inward, her eyes sink low, her posture speaks not of defiance but of concealment. Mueck magnifies the emotional weight of adolescence by scaling the figure beyond the human, as if her inner turmoil had ballooned into monumental form. In contrast, Young Couple shrinks a scene of intimacy into near miniaturisation, forcing us to draw close. At first glance, the two teens cling to one another. But his grip is just a little too tight. Her gaze is just a bit too far away. It’s the kind of subtle tension anyone who has lived through young love might recognise—how affection sometimes coexists with control, how closeness can carry quiet resistance. These two sculptures, though divergent in scale, converge on the same terrain: the vulnerability of becoming.

Woman with Shopping (2013) and Woman with Sticks (2009) extend this inquiry into the often overlooked labour of care—work that is persistent, exhausting and socially unacknowledged, yet central to daily survival. Both depict women burdened—one with bags and a baby, the other with a precarious bundle of branches. Woman with Shopping is grounded in urban contemporary life: a mother, overloaded, distracted, while her child reaches for her chest. She’s not neglectful—just somewhere else, mentally adrift. The emotional tension lies not in what she does, but in what she withholds. In contrast, Woman with Sticks carries a more archetypal charge. Her load is unwieldy, almost mythic. There is no explanation for her task, only its quiet perseverance. Bent but not broken, she becomes an emblem of unseen, ongoing effort. When read together, these works speak of female resilience—not as spectacle, but as condition.

In chicken / man (2019), a wiry man and a chicken lock eyes across a table. It’s absurd, even humorous, but charged with latent violence. The man’s grip tightens and the bird flinches. The space between them is a pressure point, swollen with unspoken meaning. The piece stages a moment of private confrontation, intimate and uncomfortable, where meaning hovers in the air, just beyond articulation.

By contrast, Mass (2016–2017) offers a radically different scale and register of inquiry. Originally conceived for the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and shown outside Australia for the first time at Fondation Cartier in Paris, where its confrontation with European audiences and a different architectural context subtly reframed the work—not just as a meditation on death, but as a global monument to collective memory, it now finds new resonance within the vertical expanse of MMCA Seoul. One hundred monumental skulls rise and tumble through the museum’s tall galleries, reconfigured not just spatially but spiritually. They form what feels like a ritual chamber with no clear origin, no explicable purpose. In this context, Mueck’s meditation on mortality becomes more than a confrontation with death—it becomes an inquiry into collective memory and cultural amnesia. There are no names. No dates. Only presence. The anonymity of the skulls, their repetition and scale, ask us not simply to mourn but to reckon. To look up, not for salvation, but perhaps for perspective.

This site-specific adaptation engages the historical weight of MMCA Seoul’s location—once a seat of political authority, now a space of cultural reflection. And it reminds us that not all memory is inscribed in stone; some is suspended in air, repeated in silence. While chicken / man and Mass are positioned far apart in the gallery and vastly different in tone, both demonstrate Mueck’s capacity to stretch emotional tension across dramatically different spatial and psychological registers.

Solitude, in Mueck’s world, is never empty. Man in a Boat (2002) and Dark Place (2018) explore interiority with quiet force. The former depicts a nude man adrift in a wooden vessel, arms drawn in, gaze fixed outward. He’s going nowhere, slowly. There are no oars, no destination. Just a sense of waiting, of drift. The open space around him amplifies the psychic space within him. Meanwhile, Dark Place reveals only a head, half-emerging from the shadow. He watches from the threshold between seen and unseen, his expression marked by a kind of internal gravity. The darkness that frames him isn’t just literal—it’s emotional. Together, these works meditate on the dimensions of aloneness: one in movement without purpose, the other in stillness without clarity.

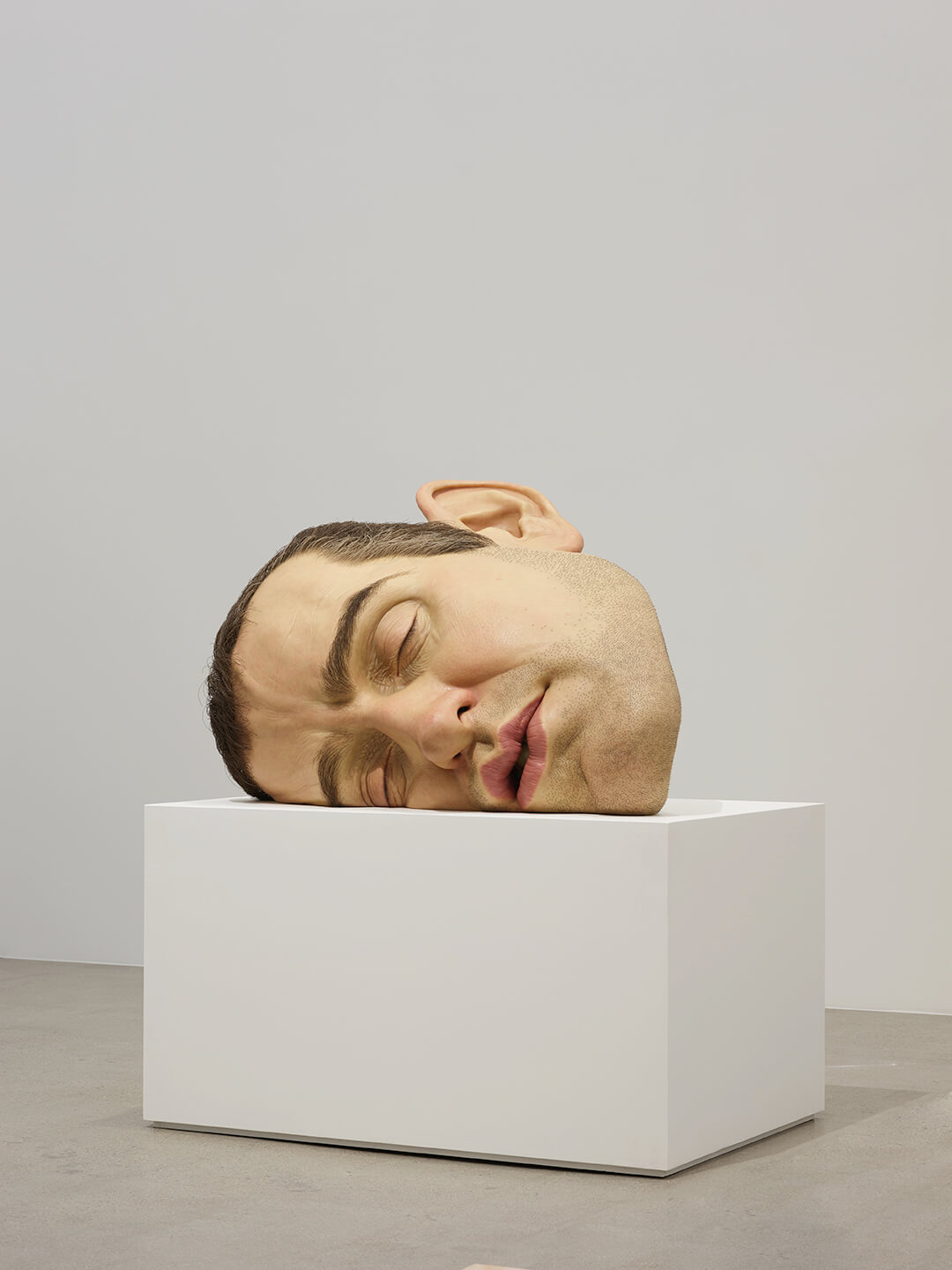

In Bed (2005) and Mask II (2002) offer another pairing—both monumental in scale, both inviting us into the private rituals of rest. In In Bed, a woman lies beneath an avalanche of white linens. Her face floats just above the sheet line, eyes open, staring nowhere. Her body doesn’t move, but her expression shifts the room. You feel the heaviness of unspoken thought, of endurance rather than repose. Mask II, a colossal self-portrait of Mueck’s sleeping face, rests on the floor like a relic. From a distance, it feels serene. Up close, it’s unsettling—the skin too still, the features too exact. The work hovers between peace and unease. Where In Bed stages emotional burden, Mask II examines emotional withdrawal.

The exhibition’s cumulative force emerges not from a single masterpiece, but from the way these pieces echo, contrast and amplify one another. Stillness becomes its own kind of movement—a rhythm felt across figures. In Mueck’s hands, scale is never a gimmick. It is grammar. It tells us how to read the body, how to feel its weight, proximity and silence. What makes this show so moving is not its scale or skill, though both are impressive. It’s the honesty. Mueck does not judge his subjects. He does not idealise them. He lets them be. And in doing so, he lets us be, too. We don’t need to understand each work. We only need to feel their presence.

Ron Mueck doesn’t offer us answers because he knows the truth rarely arrives that way. Instead, he builds quiet thresholds—moments suspended in resin and breath—that ask more of us than comprehension: they ask for presence, for unease, for a deeper kind of listening. His sculptures don’t declare; they murmur. They don’t resolve; they resonate. In walking among them, we don’t find clarity—we inherit a kind of spiritual static, a frequency tuned to what it means to endure, to ache, to feel time crawl across skin.

We exit not with insight, but with imprint—a layered accumulation of emotion, comparison and contrast that has moved through scale and solitude, intimacy and abstraction. As the sculptures mirror one another in gesture and presence, so too do they linger within us, not as individual impressions, but as a collective resonance. It is a haunting, yes—but one that reminds us we still have nerves to feel it. In a world busy explaining itself into oblivion, Mueck's art does something rare: it listens back.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.

Ron Mueck's work is on view at MMCA Seoul until July 13, 2025.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Lee Daehyung | Published on : Apr 21, 2025

What do you think?