India Art Fair returns for its 15th edition in 2024 with a new Design section

by Mrinmayee BhootJan 25, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mario D’SouzaPublished on : Jan 06, 2024

A camel delicately balanced on a harness sways while being offloaded from a ship in Southern Australia. It was one amongst thousands imported from India since the 1840s. The ungulates were initially employed in the exploration of inland territories but were eventually also instrumental in the laying of railways and telegraph networks. With the arrival of motorised modes, the camels were abandoned and grew feral. This image, an offering by Inti Guerrero, co-artistic director of the Sydney Biennale at the recently concluded Experimenter Curators hub presented the possibility of multiple epistemologies—“to embrace multiplicity, forms of identities, historic and cultural languages and to ultimately present complexity.” Not far from the hub, in Sahil Naik’s Specters, Specimens and Ships in doubt at Experimenter, Ballygunge Place, we are introduced to the Ganda (rhinoceros), a gift from the Sultan Muzafar of Cambay to the Portuguese seat in Goa as a consolation for not providing permission to build a fort in the Gujarati gulf. The beast was further gifted to King Manuel and took a long journey across the Indian Ocean only to stoke the fantasies of many, including Durer, who made an infamous, inaccurate etching of the animal.

Between the possibilities these gifts and diplomatic offerings produced, I was told a story from 1413 when sailors from Malindi arrived at the court of the King of Bengal with a host of tributes including a giraffe. Chinese Admiral Zheng learnt about the giraffe from his emissaries present in Bengal, and in turn invited the Malindians to the court of the Ming dynasty, hoping they’d bring another giraffe as a tribute. The animal was revered and equated to a qilin, and the renowned court painter Sheng Du was commissioned to paint the animal. These gifts, amongst several others, were tied to power.

Guerrero spoke of how “coastal dominance is first, but to enter interiorities,” and in some sense making place took time. This predicament connected to conversations with Naik over the past many months about the modalities of gifts during the non-aligned movement as well. Jawaharlal Nehru gifted an elephant named Indira, after his daughter, to a zoo in post-war Japan. This was in response to him receiving a letter from school children missing their beloved animal. Two decades later Indira gifted Sri Lanka the elephant to Joseph Broz Tito for his reserve in Brijuni island, along with a Nilgai and Zebu. Several institutions and museums were set up in the shadow of the travels to non-aligned summits and other diplomatic engagements. Late last year on a research visit to Mauritius, I was taken to the Mahatma Gandhi Institute inaugurated in 1976 by Indira Gandhi. Here I found a 70-foot-long Mrinalini Mukherjee mural flanking the two sides of an auditorium stage. Almost unknown in this context, the mural lives a quiet life serving as the backdrop for distastefully installed speakers. Mukherjee, amongst other artists, travelled to these places that had a strong relationship with South Asia with the movement of Indian indentured labourers and slaves. This movement of artists could also be seen in the aftermath of socialist global exhibitions of contemporary art such as the First Triennial of Contemporary World Art held in New Delhi in 1968. The exhibition responded to “shifting triangulations of contemporary art in India’s art institutions and international relations in the 1960s” and “reflects its organisers’ optimism in the capacity of art to enact change'' as noted by The Socialist Exhibitions research project. Mulkraj Anand, then Director of the Lalit Kala acknowledged the influence of Venice, Sao Paulo, Paris and Tokyo biennials. “The fight against imperialism and all its agencies is thus closely connected with the struggle for a truly modern art” read a note by British critic John Berger sent on the occasion of the Triennale's opening. The exhibition could have offered the radical recentring of the world to Asia, but it ultimately catered to the Euro-North American sensibility. Through collusion with embassies and diplomatic agents, artists were chosen either based on recommendations or selected.

This shift was an important reclamation of regional internationalism—to look at the world as it were from where one stands—crucial for reworlding and decolonising. One way is, of course, to see through movement, like with Admiral Zheng He and his imperial fleets producing a map of oceanic networks by voyage. The other is to see through imagination—like the Jesuit priest Mateo Ricci producing a map of the world for the Ming court with China at the centre in 1602. Almost against Christianity, the map depicted mythical creatures and beasts in tune with Chinese mythology to earn the favour of the Ming court towards missionary work. A compromise after all.

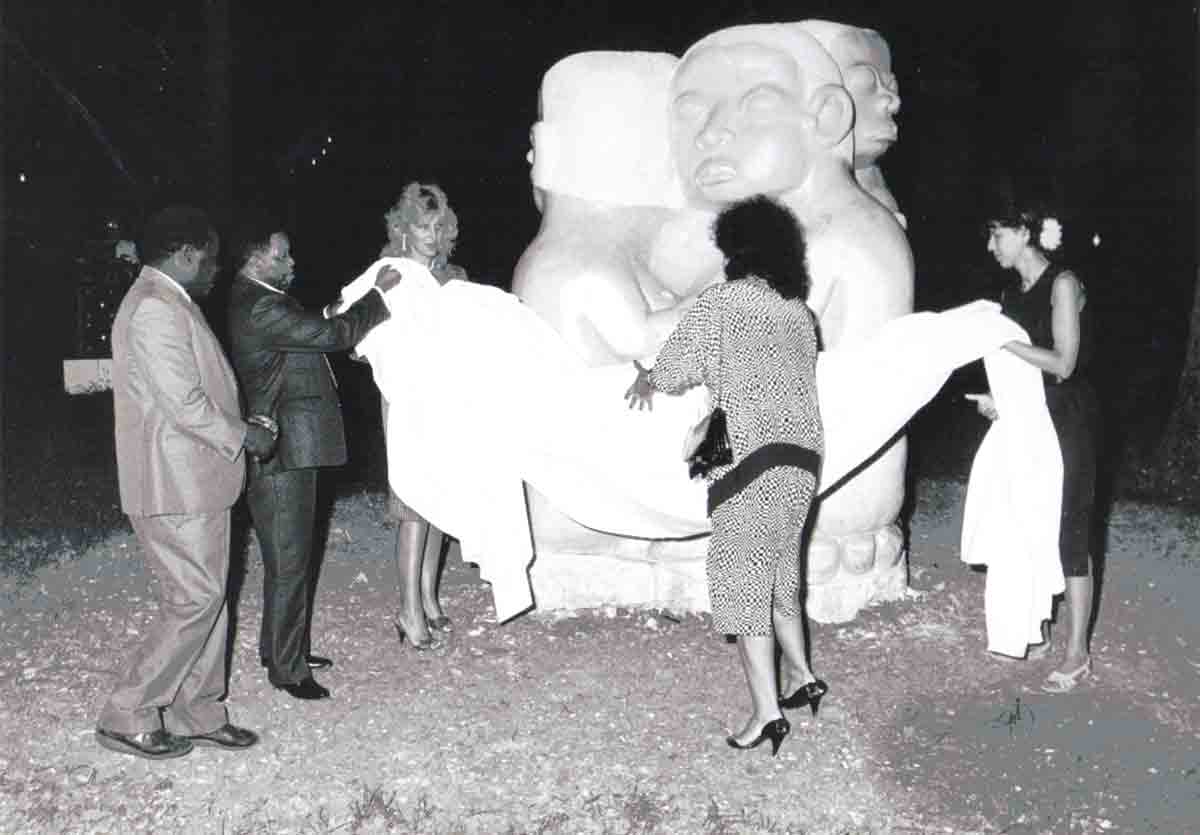

Besides animals in Brijuni, Josip Broz Tito's name was attributed to another collection of over 800 artworks from 56 non-aligned and developing countries. Classified as “gifts of the countries” or “gifts of the governments”, without specific details, the art gallery of the Nonaligned Countries was established in 1984 in Titograd (Podgorica, Yugoslavia) with “the aim of collection, preservation and presentation of the arts and cultures of the non-aligned and developing countries”. Only two cultural and art institutions namely the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi and the National Gallery of Zimbabwe were documented and in some sense curated. Although there were movements, like Yugoslavia presenting exhibitions in Harare, Dar es Salaam, Lusaka, Alexandria and Delhi; there was a lack of curatorial imagination. The absence of structure and resources provided uneven exposure. The gallery formally closed in 1995 and the works now sit in the custody of the Centre for Contemporary Art of Montenegro awaiting a second coming.

These lives and objects that traversed across two imaginations of the world and across time are eventually rendered still by historical revisions by those in power. Naik notes, “What is the life of these ‘gifts’ in the aftermath of the regime? Perhaps these objects also mutate and change identities and orientations based on who is in power or are silenced to forever remain in the backrooms of now-liberated colonial structures”.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mario D’Souza | Published on : Jan 06, 2024

What do you think?