A ghostlight in dark times: Stan Douglas’ survey at the Hessel Museum

by Paola MalavassiAug 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Diana BaldonPublished on : Jan 27, 2025

“The ocean is everything at once: a highway for the trade in goods – and people; an escape route, a fate, a source of food and raw materials, a dumping ground. And a lung,” an excerpt from the concept note for the exhibition OCEAN reads. Currently on view at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art from October 11, 2024 – April 27, 2025. OCEAN features works by more than twenty artists from Europe, Africa, North America and Asia, along with specimens and artefacts from the 18th century onwards. The premise inspiring the show may be the surge of water-themed exhibitions in recent years, but it also draws from the geography of Denmark – a country bordered by 7,300 km of sandy beaches that wash up along the shores of the Louisiana Museum, located on the strait bordering Denmark and Sweden, an area that is in great danger due to rising sea levels.

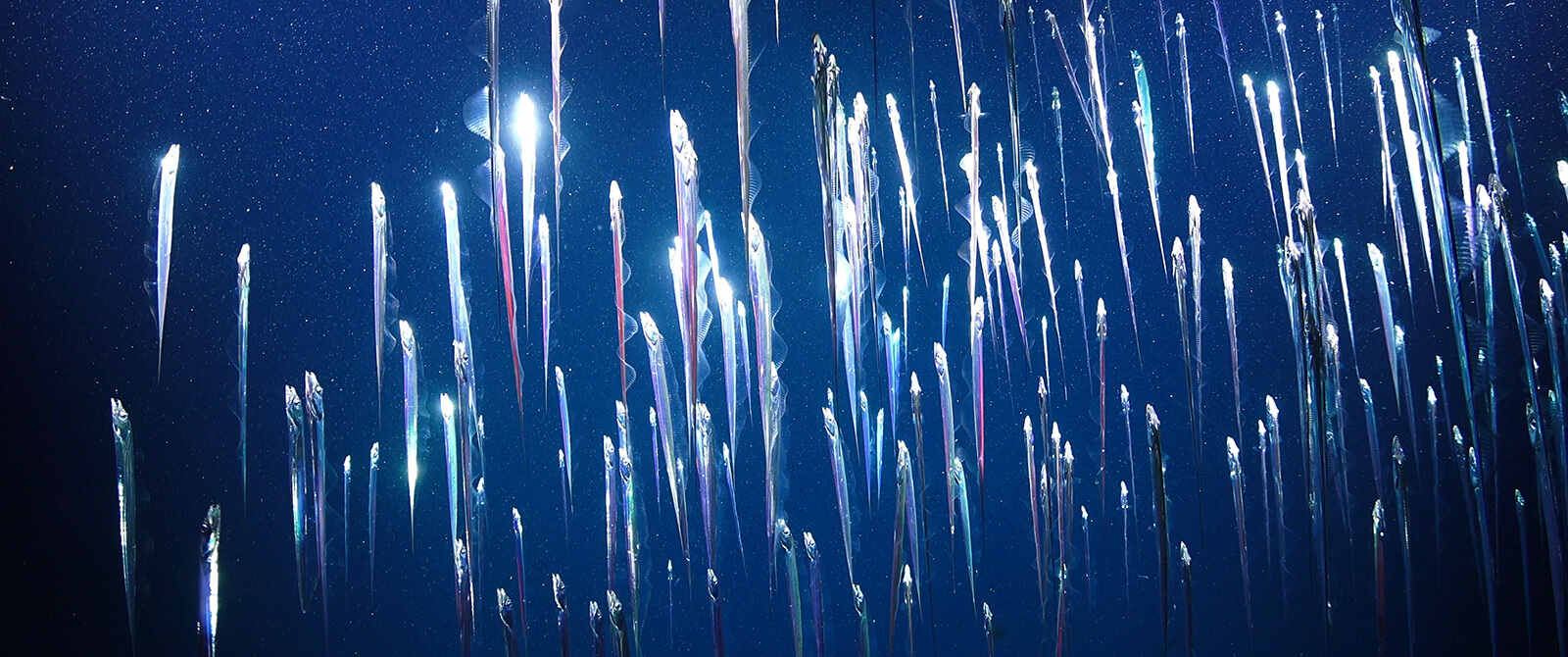

The show is organised around three subjects that are introduced by a wallpapered corridor of seaweed varieties, reproduced from cyanotypes by botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1843). Titled ‘The ocean between art and science’, the first grouping of works sits at the juncture of art and science to explore the world of deep seas. Emilija Škarnulytė’s video installation Aphotic Zone (2022) combines digital imagery of a futuristic and flooded Earth, documentary footage from a research project in the Gulf of Mexico and luminous sea jellies found in the pitch-black depths off the coast of Costa Rica. The magnitude of its soundscape is impressive; it was recorded in 2021 in Mexico City to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Spain's conquest of Tenochtitlan, the destroyed capital of the Aztec Empire, reminding us that the richest world of sound on Earth resides below the surface of oceans.

Dressed as a cabinet of natural history curiosities that capture “our fascination with sea creatures […] to be inquisitively charted, classified and conquered”, a room is dedicated to marine biology collections and conchylomania, the passion for shells. Realised between the second half of the 16th and the early 20th centuries, still life paintings by early Baroque Dutch artists Hendrick Goltzius, Willem van Aelst and Balthasar van der Ast are accompanied by didactic illustrations by marine biologist Carl Chun, oversized onto large walls, among others. Yet, the limelight falls onto the delicate glass models of marine invertebrates crafted between 1866 and 1889 by Bohemian glassmakers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. Commissioned as educational tools for the University of Rostock, Germany, these models constituted a massive leap in the field of science, enabling the study of marine invertebrates with their hyperrealistic detail.

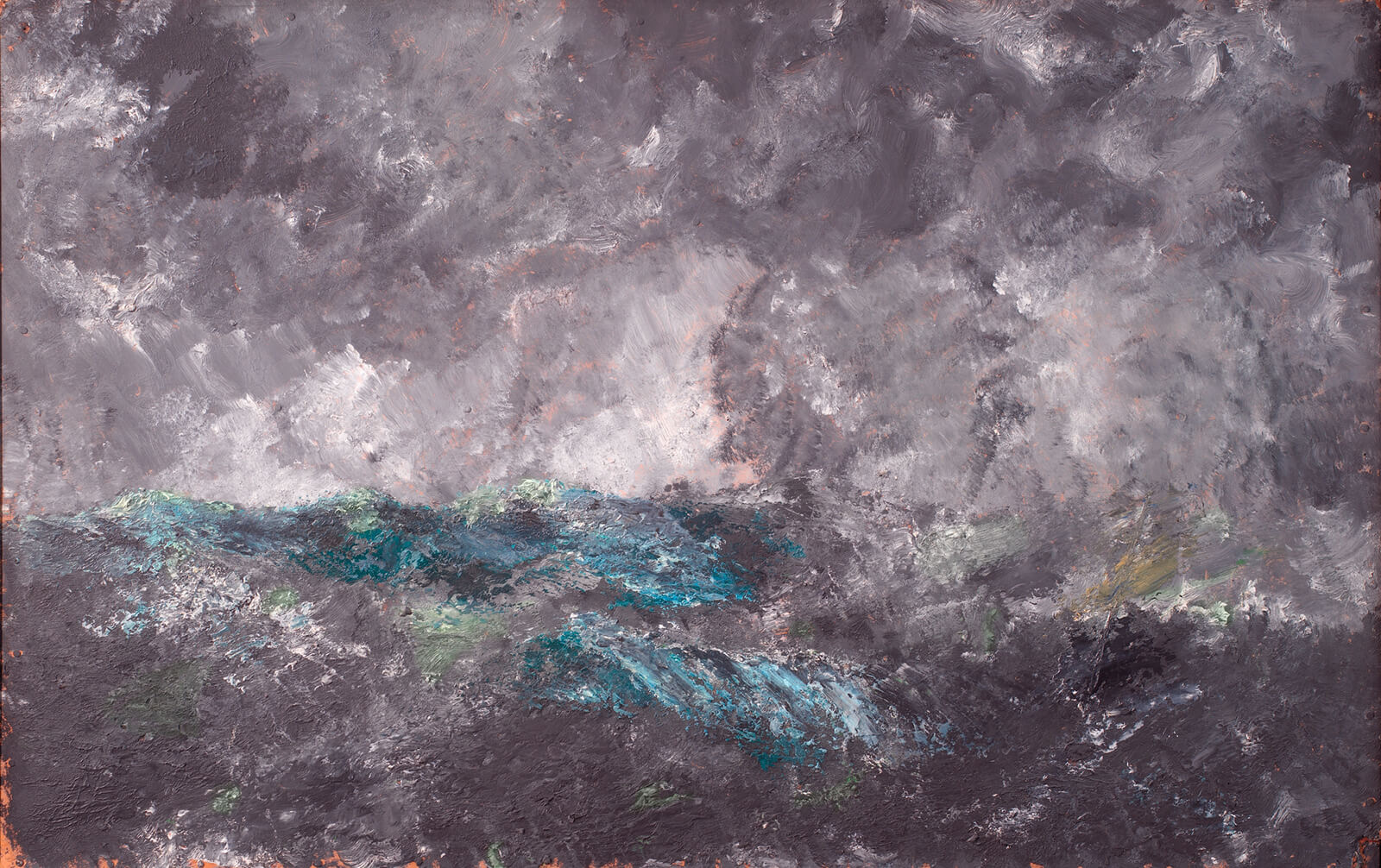

Under the heading ‘The Sublime and Mythological Ocean’, a second cluster of artworks packs several centuries of Western and non-Western art history into four rooms, including mythological figures and theories, for instance, engravings by Renaissance artists Albrecht Dürer and Andrea Mantegna featuring sea gods and monsters. In 19th century Denmark, the genre of landscape painting was tasked with allegorising human experiences and depicting the notion of a "national nature", thus presenting the condition of its beaches, but, here, to represent this idea, we find stormy seascapes by Peder Balke, Caspar David Friedrich and August Strindberg – a painter as well as a playwright – rather than by Danish masters. They face a collection of abundant ‘rough sea’ postcards that conceptual artist Susan Hiller gathered from the 1970s until her death in 2019. Found in tourist shops in coastal towns, they signify Britain as an island nation and a domesticated version of the 19th-century Romantic notion of the sublime. At odds with such a selection of works, a group of marbles of divinities from 1 BCE (likely Roman copies of Greek originals) owe their presence to the fact that, during their 2000-year burial in the sea, they were disfigured by stone-eating aquatic organisms.

A last grouping tackles, as stated in the press release, “Western colonialism as a counterpoint to white, Western mythology and its sea gods and mermaids”, seeking to connect to the colonial history of ocean conquest and Black identity politics. Works by Jeannette Ehlers and El Anatsui thematise the slave trade across the Atlantic, in which Denmark played a complicit role between 1672 and 1917 with its transport of West African people from the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana) to the Danish West Indies. Ellen Gallagher´s Fast-Fish and Loose-Fish (2023) depicts fragments of organic matter – Black people and whale skeletons – sinking in water. It comes as no surprise that this work stands in front of a listening station by the defunct techno duo Drexciya. Gallagher has been, in fact, greatly inspired by their music and story on ‘Black Atlantis’, an underwater world inhabited by descendants of pregnant West African women who drowned during the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

The last section – ‘The Anthropocene Ocean’ – turns from the premodern notion of the sea as a resource for images and texts to the realm of critical ocean studies. It highlights how oceans are now ontological places in which concepts of multispecies, feminism, fluidity, routes and mobility, among others, interact. Viewers encounter sculptures by Danish collective Superflex (As Close As We Get, 2022), designed to host marine organisms in response to a subaquatic future for humans; Pierre Huyghe's autopoietic sculpture Zoodram 2 (2010-21), that incorporates live marine invertebrates and rocks in a tank to generate a self-regulating environment that sits at the threshold of a manmade idea of nature and the physical world; John Akomfrah’s video installation Vertigo Sea (2015), depicting mankind´s relationship to the ocean through brutal histories of migration, slavery, colonisation and war; and Allan Sekula´s project Fish Story, documenting the scale and labour conditions of the shipping industry in an increasingly globalised economy, where market forces affect workers, climate and international laws.

Such an anthropocentric view of the sea is in stark contrast with other pieces in the same grouping. Microscopic wonders of the ocean, symbolised by the abstract dots of Howardena Pindell´s canvasses, are displayed alongside video reportage on deep-sea exploration in the North Atlantic, where valuable mineral reserves lie, and manganese nodules and crusts containing rare earth elements deployed in digital technologies from the Pacific and Atlantic. Another awkward pairing is Kirsten Justesen´s photographic work Mer Maid (1990) and the AI-powered video Auntlantis (2024) by the Singaporean designer who works under the alias niceaunties. A significant figure for feminist art in Denmark, Justesen plays with the lexicon of the English noun ‘mermaid’ and the Sisyphean gesture of vacuuming the sea to criticise women´s role in domestic labour as well as H.C. Andersen's fairy tale The Little Mermaid as the most essential example of Danish cultural heritage. The second work, instead, presents a posthuman scenario where old Asian women live among plastic trash and genetically modified fish reinforcing a derogatory view of older women and minimising the fight against environmental degradation.

OCEAN seems so preoccupied with retracing the chapters of the anthology Oceans, edited by Pandora Syperek and Sarah Wade and published in 2023, that it often relinquishes the ocean to a scenography, thus skirting the most urgent challenges posed by an area covering more than 70 per cent of the earth’s surface. Think of the increasing militarisation of seas, of a new phenomenology that understands the rights of oceans and rivers as political beings, of water citizenship as an emerging concept to highlight the human-ocean interconnectedness for a more sustainable future of the marine environment. It fails to mention the need to protect the rights of Indigenous communities engaged in the fishing industry, i.e. the most important economy in Greenland, which is an autonomous region within the Danish Realm where the Inuit ethnic group constitutes 90 per cent of its population.

Despite such flaws, OCEAN's transdisciplinary ambit must be praised. It displays scientific and artistic objects and images in an attempt to unify differing worldviews between the humanistic and scientific realms, as ancient cabinets of curiosities intended to do. It showcases analogue films from the turn of the 20th century alongside generative AI imagery made by free machine learning systems that disperse on social media platforms. A century and a half ago, film was a revolutionary endeavour recording movement and studying new cells and natural objects in real-time; worthy of mention is the inclusion of experimental films and photographs from the early 1930s of underwater fauna by filmmaker Jean Painlevé who “combined a scientist's eye with a Surrealist's sensibility to produce a cinematic bestiary”, as British art critic James Cahill described. Today, AI’s tacit revolution is pivoting our visual field, making us desensitised towards content optimisation and even the imitation of art, and disconnecting us from the understanding that creativity is largely dependent on collaborative work. Whether analogue or digital, these inventions shoulder the diffusion of media that in either period in history have transformed audiences into consumers of entertainment who feed the culture industry. That very same desire for entertainment lies at the foundation of the wide-ranging cabinets of curiosities that wealthy collectors from the 1500s onwards created to align entertainment with prestige and learning. Their collections are the DNA inherited by the contemporary museum whose mission – to be a reflection of our era and culture – must also encompass the need to care for the future of the ocean.

OCEAN is on view at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark from October 11, 2024 – April 27, 2025.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.)

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Diana Baldon | Published on : Jan 27, 2025

What do you think?