MuseLAB crafts an immersive lunar landscape in terracotta hues in Gujarat

by Kiranmmayie SApr 24, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Shilpa DasPublished on : Jul 29, 2021

With Gira Sarabhai's demise at age 98, an era has ended for the National Institute of Design (NID), India, losing not only its sole surviving founding parent (Gautam Sarabhai having passed away in 1995), but also a person of many parts: visionary, architect, institution builder, reverent curator of art, crafts and culture, and fierce custodian of family histories and archives. Sometime in the 1960s, celebrated architect Balkrishna V Doshi invited her to dinner at his home along with the legendary Louis Kahn. He recalls her asking Kahn to explain what architecture is, or meant to him. Kahn replied to her the next day, slipping a piece of paper to Doshi which said that “architecture is what I cannot smell nor touch but what I feel the essence of. Be it a ship, a bird, or a wall. It is the thoughtful making of space.” It is this striving towards the core idea or essence of things and thoughtful making of space that is the quintessence of all Gira ben’s work.

Gira ben was a recluse at age 90, when I met her in 2012. I had been trying to meet her without much success and eventually, renowned graphic designer, Subrata Bhowmick, got me an appointment with her in order to interview her for a book I was editing and writing that was to document the National Institute of Design or NID’s 50-year historical journey from 1961-2011. My first impression was that Gira ben commanded your attention when she entered a room. She made it clear to me at the outset that I could neither record the interview (it was not to be an interview!), nor take notes nor ask any questions. She would tell me whatever she chose to tell me. She spoke about specific events in her life in an anecdotal rather than reflective manner and I had the impression that she was holding back some of her thoughts. I sat listening in rapt attention to all that she had to say including about her brief stint of one year at Frank Lloyd Wright's studio in Taliesin, where she could see all original drawings, plans and masterpieces in the studio when they worked all night; how when she was in New York, her brother, Gautam Sarabhai, wrote her a letter asking her to visit the Royal College of Art in London to invite several experts from various fields to India and how at first, they invited Asok Mitra, popularly known as “The Father of Indian Census” to head NID. As soon as our conversation ended, I ran out of the room in the Calico Museum at top speed, plonked myself into a comfortable sofa type chair, borrowed two sheets of paper and an 8B or 9B pencil with a rather blunt point, and scribbled away at top speed everything I could recall. At the age of 90, she stood ramrod straight, walked without stooping and spoke decisively, clearly, even dare I say, imperiously.

I was totally in awe of her.

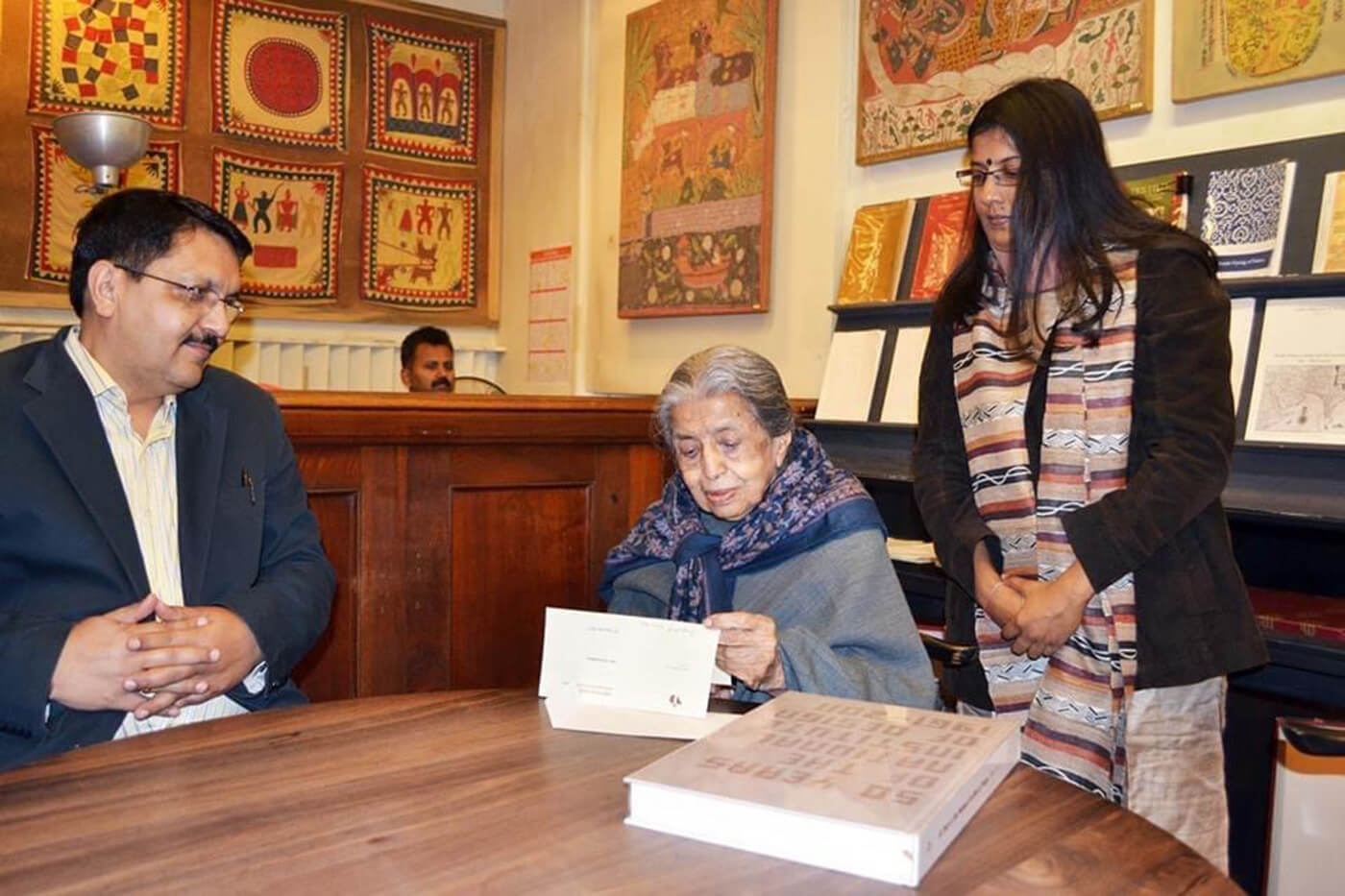

When I met her again in 2013 to hand over a copy of the NID history book, she was enthusiastically making plans for and directing a book that chronicled the historical legacy of the Sarabhais, the elite and industrialist but progressive family from Ahmedabad that she was born into that included freedom fighters, educationists, scientists, environmentalists, social reformers, and artists besides industrialists. The book was subsequently published by her in 2018. With an assiduous and unerring eye for archival detail, the book charts out the role of the family in establishing some of Ahmedabad’s finest institutions in fields as varied as art, architecture, the sciences, management, design, education and social work. The contributions made by these institutions were as much avant garde for their time as they were transformative.

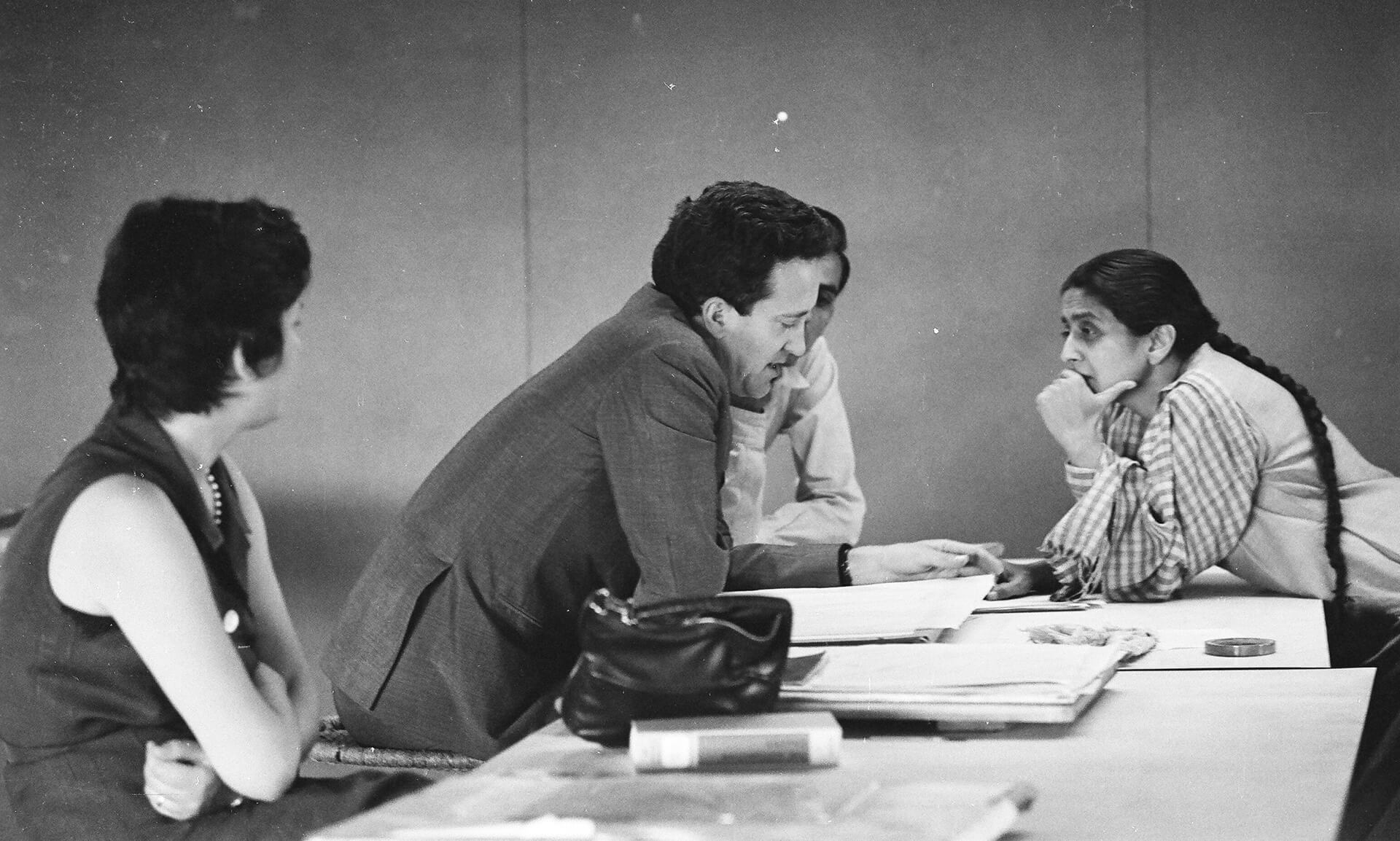

Ambalal Sarabhai and Sarla Devi, her parents, extended their hospitality to a distinguished list of luminaries. These visitors, most of whom stayed with them in their home, included Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, the Nehrus, Annie Besant, Maria Montessari, EM Forster, Sir CV Raman, Isamu Noguchi, Alexander Calder, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Henri Cartier- Bresson, Louis Kahn, Frei Otto and Vallabhbhai Patel among scores of others. Such a home environment shaped the children’s minds right from the formative years of childhood. The Sarabhais were also patrons of modern architecture, and instrumental in bringing Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn to India. Their propitious national and international connections with several eminent Indian and international professionals drawn from various fields including design such as the Nehrus, Pupul Jayakar, Charles and Ray Eames, and Douglas Ensminger of the Ford Foundation led to the conceptualisation and vision of the national level design school they envisaged. Those who participated in the protracted discussions on design and the institute included, besides Gira ben and Gautam bhai, their brother, the eminent scientist Vikram Sarabhai, Douglas Ensminger of the Ford Foundation, BV Doshi, Kamal Mangaldas, Ravi J Matthai and Kamala Choudhury from the Indian Institute of Management, Kamalini Sarabhai, Director of the BM Institute of Mental Health, and the first two design teachers at NID, Dashrath Patel and H Kumar Vyas.

Gira ben was the first honorary Chairman [sic] of NID’s Directing Board from 1964 to 1972 while Gautam bhai was the Chairman [sic] of its Governing Council. At the time, she had already been the Art Director of Shilpi Advertising Limited since 1948. Owned by the Sarabhais, it was, arguably, the first advertising agency in India. She also had, inspired by Dr Ananda Coomaraswamy, already set up the extraordinary Calico Museum of Textiles in the mill premises which was shifted to the Sarabhai Foundation in 1982. Most people who know her from the early days of NID, describe her as an austere figure, usually dressed in white, a strict disciplinarian who did not tolerate either a casual approach to work or dereliction of duty. As soon as she entered the campus, the news would spread that she had arrived and everybody would scurry to their seats because she had the habit of walking up and down the entire building. By her own admission, she had little time or patience for idle chitchat and believed in her work speaking for her. She was a perfectionist, enthusiastic and passionate about her work and expected all work at the Institute to meet her rigorous standards. She was also self-effacing, maintaining a low profile, never wanting to be in the limelight and letting Gautam bhai be at the forefront. She was the one who looked into the day-to-day affairs of the Institute, and took most of the decisions, and was the creative head behind any conceptualisation or decision making. Bhowmick once told me that “Gautam bhai was a calculator and she, the finger. You did not see her teach but she would interact with everyone on campus. She was the real architect of design education.”

BV Doshi once spoke to me about Gira ben and Gautam bhai's basic sensitivity as Indians and core cultural ethos, which he deemed to be unparalleled. He remarked, “Despite the high exposure they had to the world outside, they believed in our unique identity as Indians. And I think that is why you see the Calico Museum to be as outstanding as it is, the precise way the artefacts are displayed and preserved, and the almost ritualistic manner in which the guided visits are conducted. That is also how they lived. It is very unusual and remarkable. Non architects doing architecture! This is rarely found.” To Doshi, the basis of NID was the Sarabhais’ rediscovery of India and the creation of an Indian identity similar to the efforts made by the Japanese, or Italians or Europeans. He added, “This is exactly what Gandhi meant when he said, “Keep all the windows of your house open so that the fresh breeze from the world can come in, but take care that your roof is not blown away by ensuring it has a strong foundation. And I think this is what the NID ethos is”.

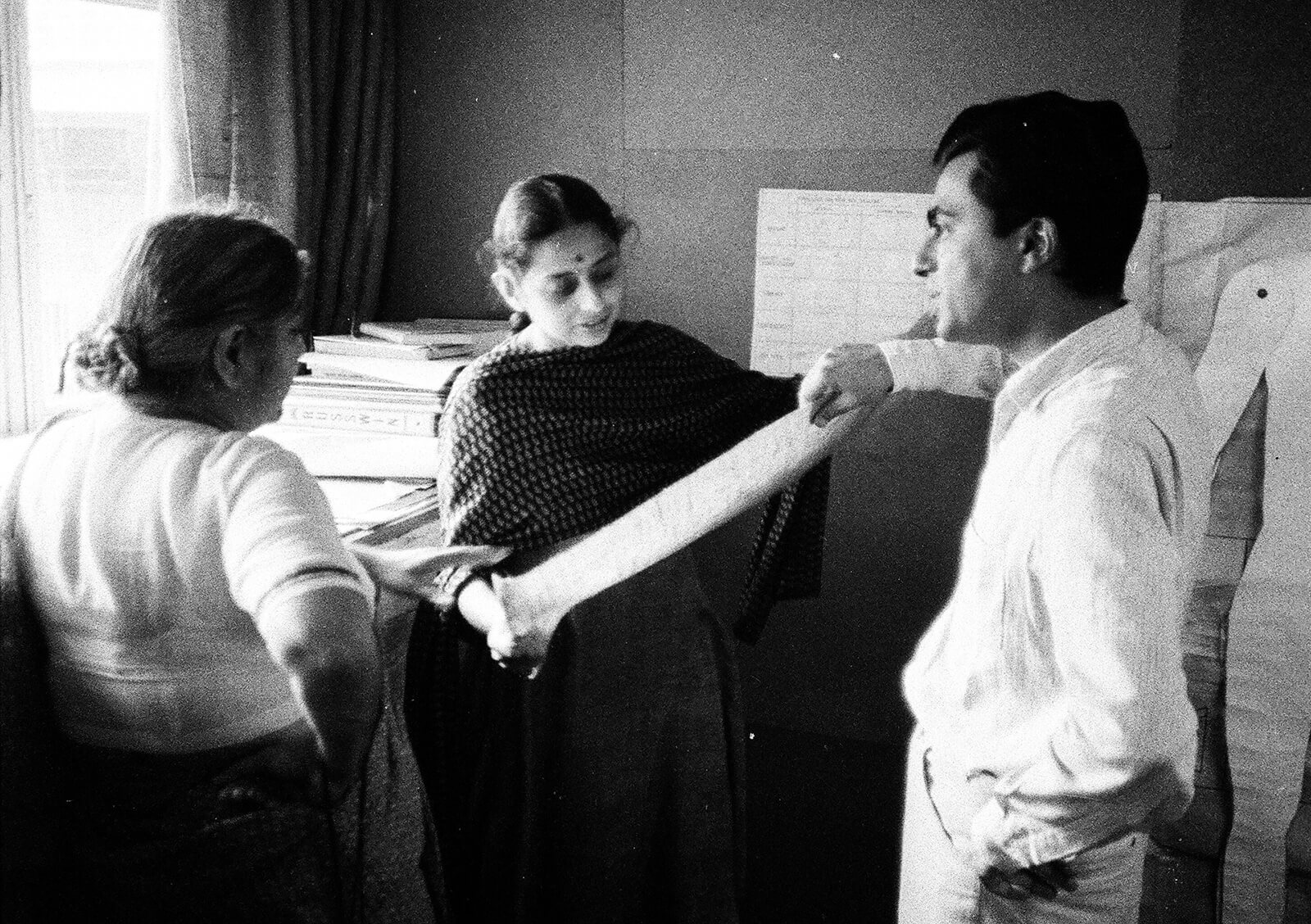

Despite not having any formal education in architecture, Giraben’s contribution to modernist architectural projects in Ahmedabad and Bombay by way of iconoclastic public buildings is widely acknowledged. However, she shrugged off the label of an architect and preferred calling herself a designer. A recent book by architect and academic, Madhavi Desai, places her, rightfully so, in the modernist architectural canon at the forefront. Desai highlights the first space frame structure in India, the Calico Dome, for which Gira ben did the detailing based on Buckminster Fuller’s principles and for which Gautam bhai gave the engineering concept. In fact, the two siblings made for an interesting professional pairing, complementing each other’s abilities and often working together on several innovative projects. One such project was the NID building, the first public building they designed in Ahmedabad. I recall an informal conversation I had one winter afternoon with Professor Kumar Vyas when he said, “Gautam had the concept (of the building) in his mind, the totality. And Gira would get into detailing out the whole thing. It was really amazing to watch them. I saw this building being planned in the museum designed by Le Corbusier, across the road from NID, where the Institute was housed for a few years at first, and that was how they worked together. There were not many drawings. It was all just little sketches. It was only towards the end that they made a model.” The institute was at first referred to as the National Institute of Industrial Design; then called the National Design Institute. A name that was changed yet again to the National Institute of Design to better suit Adrian Frutiger’s logo design for the Institute.

When planning for the new campus started, Professor Stien Eller Rasmussen, Charles Correa’s teacher, was invited to discuss his ideas on the design. At one point, Danish architect, William Vohlert, was seriously being considered to be the architect for NID. The Sarabhais asked various people for their ideas, sketches and drawings. They decided to appoint an American architect and asked him to present his concept for the building. The design turned out having neither straight lines nor right angles and had diagonal spaces instead. After reviewing these and other designs, they decided to design and construct the building themselves and muster all their 'in-house' resources to work on the project, which would also provide an excellent learning opportunity to the first cadre of students. They even considered having a temporary structure for the institute and Gira ben made several conceptual sketches for the metal structure; some of these structures were designed and executed, but the idea was short-lived. They realised the need for a permanent structure to fight the harsh climatic elements. Giraben’s training with Frank Lloyd Wright came handy and her tremendous understanding and sense of space made her the main architect of the vision Gautam bhai and she had of the Institute’s new building as an embodiment of its physical and philosophical principles. The building’s plan laid precedence on function over form, allowed for flexibility, future expansion, adjustments and less maintenance, and was far ahead of its time.

László Moholy-Nagy, a Professor at Bauhaus, famously said that design is an attitude of the mind. “The designer must see the periphery as well as the core, the immediate and the ultimate, at least in the biological sense… must anchor the special job in the complex whole. The designer must be trained not only in the use of materials and various skills, but also in appreciation of organic functions and planning, and must know that design is indivisible.” The aim of the core building at NID was to provide an environment that would nurture attitudes and behaviour consistent with the institute’s educational purpose. The building conceived of design as a bridge between the traditional and the modern and was much inspired by the traditional built forms of Gujarat with a large landscaped courtyard. The new building materials they used—glass and concrete—embodied the modernist visual language with its allied material and technology. It was made with great precision and extremely well developed structural and material understanding. With the Sabarmati flowing adjacent to the campus, it was a high flood zone and so, the entire building was built on pilotis. GS Ramaswamy, director of the Structural Engineering Research Centre (SERC), Roorkee, was invited to create the structural design for the main 40x40ft roof shells. Advanced building techniques using waffle slabs and funicular shell constructions were deployed.

The Sarabhais and their team of advisors meticulously worked upon the architectural plans that envisaged studios, workshops, laboratories, seminar and lecture rooms, library and offices as part of the main complex. A unique system of one metre cantilevered beams running around the building was designed to house all services to make repair work easy and make for the building’s visual appeal. The detailed elevations and plans were then prepared by their draftsperson, VS Mistry. Everything was methodically detailed out—the quality, finish, joinery, aesthetics and the cost. Every brick coming to the site was tested for quality and strength. NID lore says that Gira ben had such an exacting eye that she could spot a nail not hammered in straight.

She also had an inherent skill for identifying suitable design talent and invited the best of people to join the Institute such as the first two teachers, renowned photographer, sculptor and ceramicist, Dashrath Patel and H Kumar Vyas who had studied Industrial Design at the Central School of Art and Design in London. Her role in the genesis of various design disciplines at NID, and especially in the textile design discipline, is significant too. It was she who persuaded Royal College of Art alumni, Shona Ray, and Cranbrook Academy of Art alumni, Nelly Sethna, who headed the Design Studio at Bombay Dyeing in Bombay, to join NID as consultants in 1965 in order to establish the Textile Design studio of the Institute. Gira ben pulled a few strings in the process, since Jimmy Gazdhar who was on the Board of Bombay Dyeing was also on the Board of Calico Mills. She had an eye on Nelly ever since she first met her in 1960 at an exhibition of the latter’s work in Bombay, and had invited her to join the Calico Mills. She also invited, in 1968, at Nelly’s behest, Finnish textile designer, Helena Perheenthupa, to set up the Textile Design discipline at NID. Helena went on to play a stellar role in shaping the curriculum of Textile Design for generations to come. She not only personally handpicked the people she wanted for the different departments at NID but also gave them many opportunities to travel overseas and broaden their exposure.

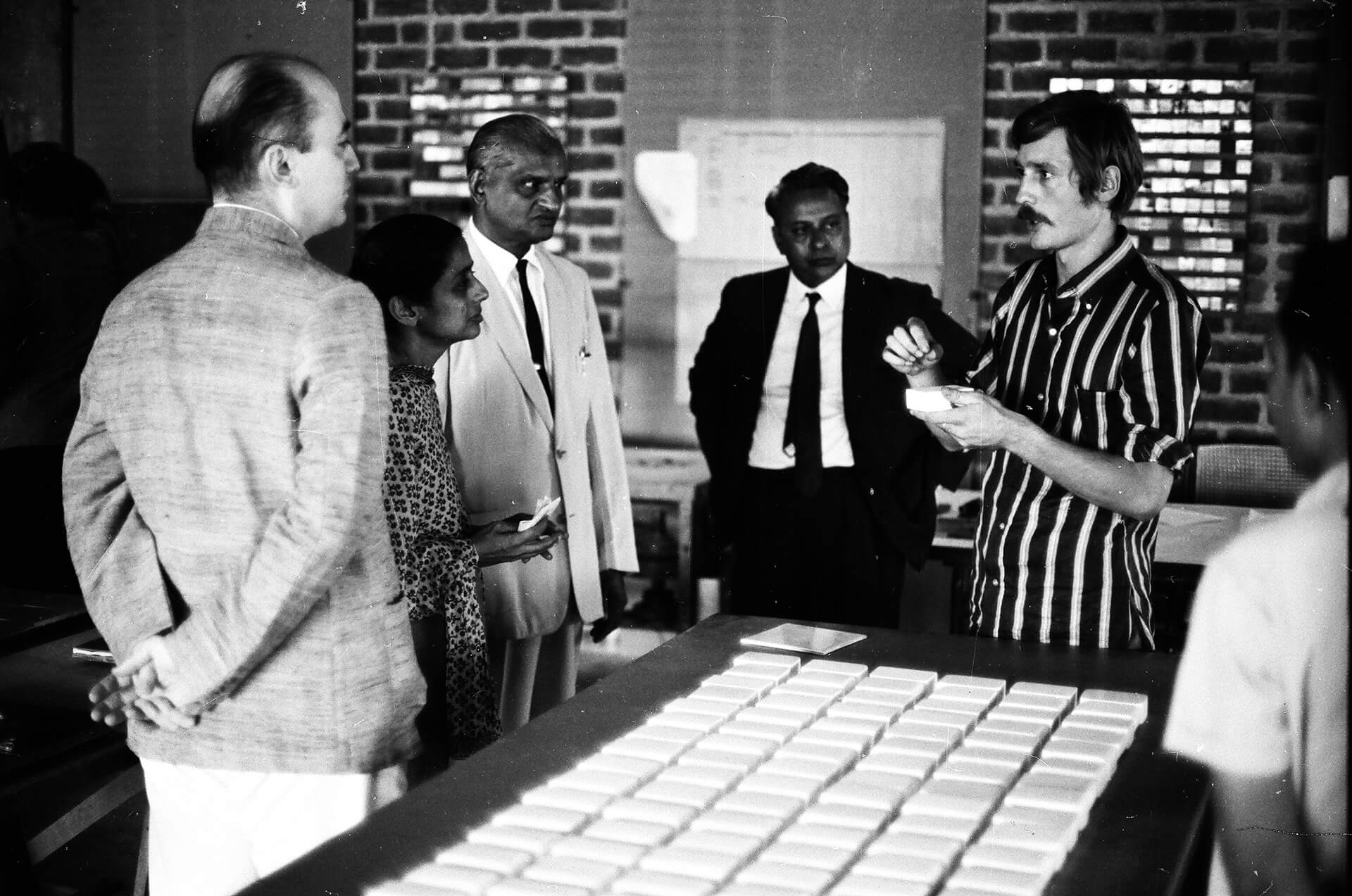

Few people know of the crucial role Gira ben played in developing NID’s unique Resource Centre in the early years. This centre was conceived of as a repository of printed and audio-visual reference materials relevant to the study of design. She devoted considerable time in selecting items for a prototype collection at the centre: furniture, tableware, cutlery, crockery, kitchen tools and implements, office equipment and fixtures, samples of textiles, ceramic materials, and building hardware. She ensured that the collection included documented information on materials, designs, and manufacturing methods employed for creating those objects. She selected thousands of magazines, periodicals and books, including some rare and out-of-print books on India for the institute’s library that was part of the Resource Centre. She ensured the archiving of audio-visual material in the form of tapes, slides, microfilms, and prints. She invited Monroe Wheeler of the Museum of Modern Art, Dean Sert of Harvard University and James Prestini of the University of California, Berkeley, to visit Ahmedabad to help prepare the bibliographical resources available on the relevant subjects of the time that would form the nucleus of the library’s collection. Shortly afterwards, the Centre built up one of the best music collections in India at the time comprising Indian and Western classical music, jazz, pop, electronica, and folk with the help of her musician sister, Gita Mayor. She also initiated two invaluable documentations at NID when the Institute commenced: Mata ni Pachedi by Joan Erikson, and Rural Craftsmen and their Work by German ethnologist, Eberhard Fischer and well-known artist, Haku Shah.

Generations of students have graduated from NID and owe a huge intellectual and every other kind of debt to the visionary Sarabhai duo. Generations of NID students have learnt as much from the incredible Calico Museum of Textiles that she set up in the Retreat. To pay homage to her memory, let me recall the profound words of scientist and educationist, Professor Yashpal, in a lecture delivered at the NID auditorium in 2012, "Khusboo zinda hai". Giraben’s legacy will stay alive.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Shilpa Das | Published on : Jul 29, 2021

What do you think?