Shimabuku in Spain: A playful confluence of art, nature and community

by Erik Augustin PalmOct 05, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Erik Augustin PalmPublished on : May 20, 2024

The Yokohama Triennale, a fixture in the contemporary art world since its inception in 2001—and Japan’s seminal inner-city Triennale—has often acted as a barometer for the cultural and social currents of our time. The 8th edition, titled Wild Grass: Our Lives, is inspired by the tenacity and upheaval depicted in Chinese dissident writer Lu Xun's prose-poem collection Wild Grass (1927)—a book that uses allegory and metaphor to critique early 20th-century Chinese politics, society and traditional values, highlighting individuals' struggles with societal pressures and historical changes. The exhibit draws from this base, offering both literal and figurative spaces to confront and contemplate today's global issues of climate change, economic disparity and authoritative legacies.

Mainly unfolding in three locales—the newly renovated Yokohama Museum of Art (the Triennale’s headquarters), the historic Former Daiichi Bank Yokohama Branch and the adaptive BankArt Kaiko set in a former Imperial Silk Warehouse—this iteration aims to show the interplay between global crises and individual narratives of endurance. However, some artworks included do not distinctly align with this theme and appear to have been selected primarily for their creators' credentials. For example, consider the broken violin from the late iconic Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto—from a 2006 performance at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art to honour the pioneering video artist Nam June Paik. An interesting artefact, but why is it placed here?

The intentions of the Triennale’s artistic directors, Liu Ding and Carol Yinghua Lu, have been to create a sense of chaos through the placement of works that see pieces installed in close proximity to audio bleed, partially to reflect the disorder of our shared current reality. However, it is sometimes unclear whether the chaos perceived is intentional or simply a result of the inability to weave a coherent narrative among all the 93 exhibiting artists from around the world. This feeling of fragmentation, though, is not exacerbated by the physical expansiveness of the Triennale across multiple venues.

On the contrary, walking between the main venues near the port of Yokohama offers a refreshing pause amid the intense array of artworks that delve into the human struggle across diverse situations. It also gives you a sense of Yokohama as a highly capable site for art, often standing in the shadow of its neighbour, Tokyo. Speaking to STIR, Kuraya Mika, the executive director of the Triennale and the director of the Yokohama Museum of Art, says she sees the event as a dynamic interface between local and global narratives.

“The cultural climate of Yokohama, where the global landscape and ordinary daily life coexist, has greatly influenced the Yokohama Triennale,” Kuraya explains. She is keen on the Triennale fostering a deeper understanding of global issues through local lenses, emphasising that "to know about the world is to know about one's immediate neighbours."

This perspective is crucial as the Triennale continues to evolve against a backdrop of increasing international art events in Asia, such as the newly sprung Art OnO in Seoul. Kuraya advocates for a collaborative spirit: “I would like to explore avenues of solidarity, such as establishing cooperative themes and sharing information on artists.”

And with 93 artists, including 31 making their debut in Japan, the Triennale certainly has enough to share. However, this number of artists, amidst all the stated topics of the exhibits—framed by a deeply philosophical approach to historical and contemporary crises, ranging from global pandemics to ideological shifts and activism—can sometimes create a feeling of being overstuffed. On the other hand, this vast span of overlapping issues also gives the viewer a choice to pick and choose what to focus on.

Lu Xun was a unique voice of dissent in 20th century China, often standing alone—and the curators have indeed crafted an exhibition that serves as a contemporary reflection of Lu Xun's intellectual inquiries, aiming to capture the cyclical nature of human crisis through dispersion of works across thematic chapters.Our Lives—focused on social activism and pressing issues of today like war, refugees and the suppression of individual freedom—is one of the real highlights of the Triennale. It is cleverly what first meets the visitor when entering the grand entrance hall of the museum. There, the asymmetric, red fabric intricately woven over steel ribs, by Congolese-Norwegian artist Sandra Mujinga (And My Body Carried All of You, 2024), majestically dangles in the air, somehow both sheltering the viewer, as well as perhaps signifying the blood that has been shed in some of the horrendous ongoing atrocities in our world.

Ascending the escalator to a new level, visitors experience a seamless thematic transition to the chapter Fires in the Woods. This section draws on historical events to reflect on modern issues like oppression, racism, activism and their impacts, using the metaphor of fires and sparks to link past conflicts and confrontations with current struggles.

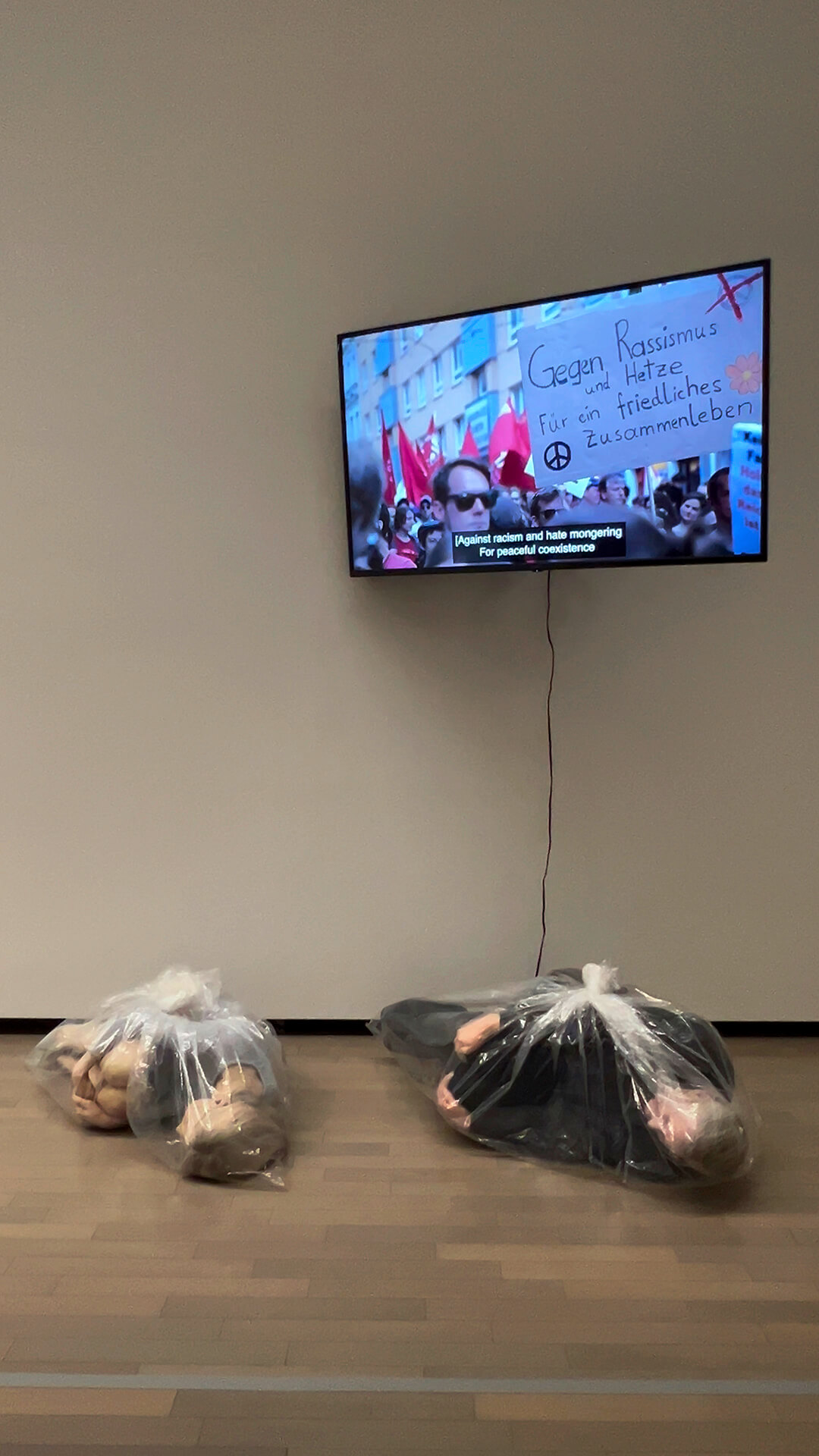

The poignant pairing of Josh Kline's sculptures—a man and woman in fetal positions encased in life-sized plastic bags, titled Wrapping Things Up (2016)—with Tomas Rafa’s video, V65: Far Right Identitarians Protest Against Refugees in Vienna (2016)—depicting a high-profile protest by the far-right Identitarian movement in the heart of Vienna—intensifies the Triennale's focus on confronting injustice.

The chapter Symbol of Depression, though more impenetrable for the viewer, also explores oppressive socio-political environments— drawing its title from a 1924 book by Japanese writer Kuriyagawa Hakuson. In the same year, while completing Wild Grass, Lu Xun translated Kuriyagawa's work. Featured artworks include a readymade sculpture exhibited by Hong Kong-based artist Vunkwan Tam—a 19th-century sword of North African origin, which he acquired through an online shopping platform—juxtaposed with Zhao Wenliang’s landscapes and portraits from the Cultural Revolution.

Speaking to STIR, Liu and Lu comment on the subtle melancholy of these artworks: “They speak volumes about the presence of individual subjectivity as much as moments of direct confrontations,” they say, emphasising Tam’s and Wenliang’s quiet but resilient expressions.

But the 8th Yokohama Triennale is at its best where it's slightly louder. Like at BankArt Kaiko where Pyae Phyo Thant Nyo, an emerging artist from Myanmar, has his installation A Story of Our Lives (2024). The biomorphic sculpture features numerous intertwined green and black wires, highlighted with small red lights. The eerie presence of these pieces hints at the hidden data-mining systems that, out of sight, monitor our actions with often exploitative and nefarious intentions.

Despite its issues—perhaps overpopulating the venues and featuring some artists largely for their reputations at the expense of the theme—the 8th Yokohama Triennale still emerges as a significant undertaking, adeptly leveraging the arts to spark critical conversations about survival, resistance and renewal. At its most compelling, the Triennale prompts visitors to reevaluate their roles within both global and local narratives, creating a space where art not only reflects but actively interrogates our shared realities. Ultimately, the exhibition stands as a tribute to the resilient and untamed "wild grass" of the human spirit and our creativity, flourishing against formidable odds and cultivating fertile terrain for new insights and connections.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Erik Augustin Palm | Published on : May 20, 2024

What do you think?