A house turned on its ear

by Vladimir BelogolovskyApr 29, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Oct 25, 2023

Just like art and literature are compartmentalised into various styles and genres, so is architecture: Classical, Baroque, Modern, High-tech, or Post-Modern to name just a few. One particular breed of mother of all arts that’s being increasingly discussed beyond professional circles is referred to as environmental. This category may sound misleading. Don’t all buildings deal with the environment, whether built or natural? They do, but only the ones that do it responsibly, are qualified to be included in this category. Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, a multimedia exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan, is now on view until January 20, 2024. It examines over 150 built and unbuilt projects from the time span between the mid-1930s to the late 1990s; they address various aspects and challenges of the environment head-on. By highlighting these works, the show’s curator, Carson Chan, the inaugural Director of MoMA’s Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment, which was established in 2020, traces the rise of the environmental movement in the United States and how it influenced the practice of architecture.

Let’s be clear: the so-called environmental architecture was always and continues to be treated as a sort of counterculture. Apart from the show’s four iconic projects—Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (Mill Run, Pennsylvania, 1934-37) and Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House (Dwelling Machine, Wichita, Kansas, project, 1944-46), Geodesic Dome over Manhattan (a visionary project, 1960), and the US Pavilion at Montreal’s 1967 Expo (in collaboration with Cambridge Seven Associates)—it is likely that the visitors will encounter all other works for the first time. For example, none of the projects on display, except for the aforementioned, are included in Kenneth Frampton’s Modern Architecture: A Critical History, arguably the profession's most authoritative volume on 20th century architecture and a required textbook by architectural departments around the world. This revelation, that lesser-known works have become so much more relevant now, makes MoMA’s retrospective quite crucial and timely due to the fact that our failure to deal with climate change issues urgently and systemically is on everyone’s mind.

Despite not being a large exhibition, the material gathered here can be overwhelming for those visitors who want to examine it in detail. Many of these projects are presented with detailed architectural models, archival drawings, renderings, photographs, maps, videos, and audio recordings. They are accompanied by short descriptions that entice further inquiry. There is no one way of experiencing the show. There is no explicit structure and no conclusive view; it is open-ended. Projects are dispersed throughout an open-plan dramatically darkened rectangular gallery on the museum’s third floor that can be entered from four(!) different ends. The show’s catalogue is not put together chronologically or thematically either; for the sake of objectivity, it lists the featured case studies in alphabetical order, according to their authors’ and participants’ last names, equating world-class architects and artists with political organisations, scientists, delineators, and volunteers.

An exhaustive 13-page-long timeline that concludes the catalogue and is reproduced in part on one of the exhibition’s walls puts things in perspective. It highlights “significant moments in the formation of environmental architecture”—from the founding of the American Society of Heating and Ventilation Engineers in 1894 and the 1969 disastrous oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, California; to the first Earth Day held on April 22, 1970, that saw more than 20 million participants across the US; to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol which has set binding targets for 37 industrialised countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The timeline reminds us that the US has not ratified these protocols to this day. Another date is highlighted both in the exhibition and catalogue: “1945: The United States drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, and another one on Nagasaki three days later. The nuclear fallout contaminates the land, air, and water, causing long-term health and environmental damage.” No lost lives are mentioned. An oversight? The abundance of text and documents that bring into light protests and legal battles of the environmental movement contrasts sharply with many of the design projects. So much so, that at times, I felt I was tackling two different exhibitions at once.

Among the most dominating figures in the show, entirely expectedly, is Argentinian-American architect, designer, and curator, Emilio Ambasz who has been long referred to as the “father, poet, and prophet” of green architecture for his missionary obsession with merging buildings with landscape delightfully. His commendable creations are 100 per cent buildings and 100 per cent gardens. In other words, the footprints that his buildings occupy are covered entirely, or nearly so, by accessible gardens. The architect’s very first project, Casa de Retiro Espiritual, originally designed in 1975 and built outside of Seville in 2005, the year MoMA exhibited it in a single-project show, In-Depth: The House of Spiritual Retreat by Emilio Ambasz, is among the most radical and eloquent green manifestos. Its towering open-book-like image with a jutting corner balcony from which one could be easily persuaded that architecture, nature, and history can co-exist harmoniously. In all of his buildings, Ambasz weaves masterfully traditions, narratives, myths, dreams, aphorisms, and rituals; it makes his architecture welcoming, humane, and desirable. Ambasz started his career as a Curator of Design right here at MoMA where from 1969 to 1976 he created several influential exhibitions. One of them, perfectly relevant to the current show, was his 1976 presentation of the work of Luis Barragán, which turned into a discovery of this Mexican architect to America and the world; the show’s catalogue was Barragán’s first monograph.

Apart from Casa de Retiro Espiritual whose model sits comfortably like a sphinx here at the gallery, Ambasz’s work is represented by three additional projects: Lucile Halsell Conservatory built in San Antonio, Texas in 1982; Prefectural International Hall built in Fukuoka, Japan in 1990; and Eni SPA Headquarters, planned in Rome, Italy in 1998, but never built. All four projects are shown with models and photos. Each deserves an in-depth report, but let me briefly touch on just one of them, the building in Fukuoka.

In search of income, the city government decided to develop half of a two-hectare Tenjin Park in the city centre. Fukuoka residents protested, so the local government had no choice but to call for a competition. Ambasz was among the three invited architects to submit design proposals. The late Kisho Kurokawa, a native of Fukuoka, was the jury’s favourite. But unanimity was not reached and the project’s fate went into the hands of the region’s governor. In the meantime, the press obtained the proposals’ photos and asked residents what they preferred. Ambasz’s vision overwhelmingly won their support, recognising the architect’s ingenious solution. He covered his building’s back with 14 accessible and interconnected park terraces—one per floor—effectively extending the existing park upward, toward the sky. Thus, Ambasz was able to give the citizens their beloved park back and enable the government to build an iconic building that since has become Fukuoka’s most celebrated public structure. The project proved that the natural environment could coexist with the built one in dense urban centres. Since then, cities around the world recognised the beneficial power of green spaces. No longer such buildings are a novelty.

Next to Ambasz, visitors will encounter the work of architect and environmental artist, James Wines, the founder of New York-based SITE (Sculpture In The Environment) who apart from realising many of his green projects wrote now seminal Green Architecture (TASCHEN, 2000), which is included in the catalogue’s timeline. The very essence of the architect’s work is expressed in his experimental big box stores for BEST Products Company. Nine such structures were built across America from 1972 to 1984. Only one, the Forest Building in Richmond, Virginia, completed in 1980, remains standing. Following the company’s bankruptcy, it was converted into a community church. BEST stores provoked conversations, ambiguity, questioning, amusement, as well as misunderstanding, and even protests by placing art where people least expect to find it. With all his works the architect teaches us how to be more observant, curious, and critical of our everyday environment.

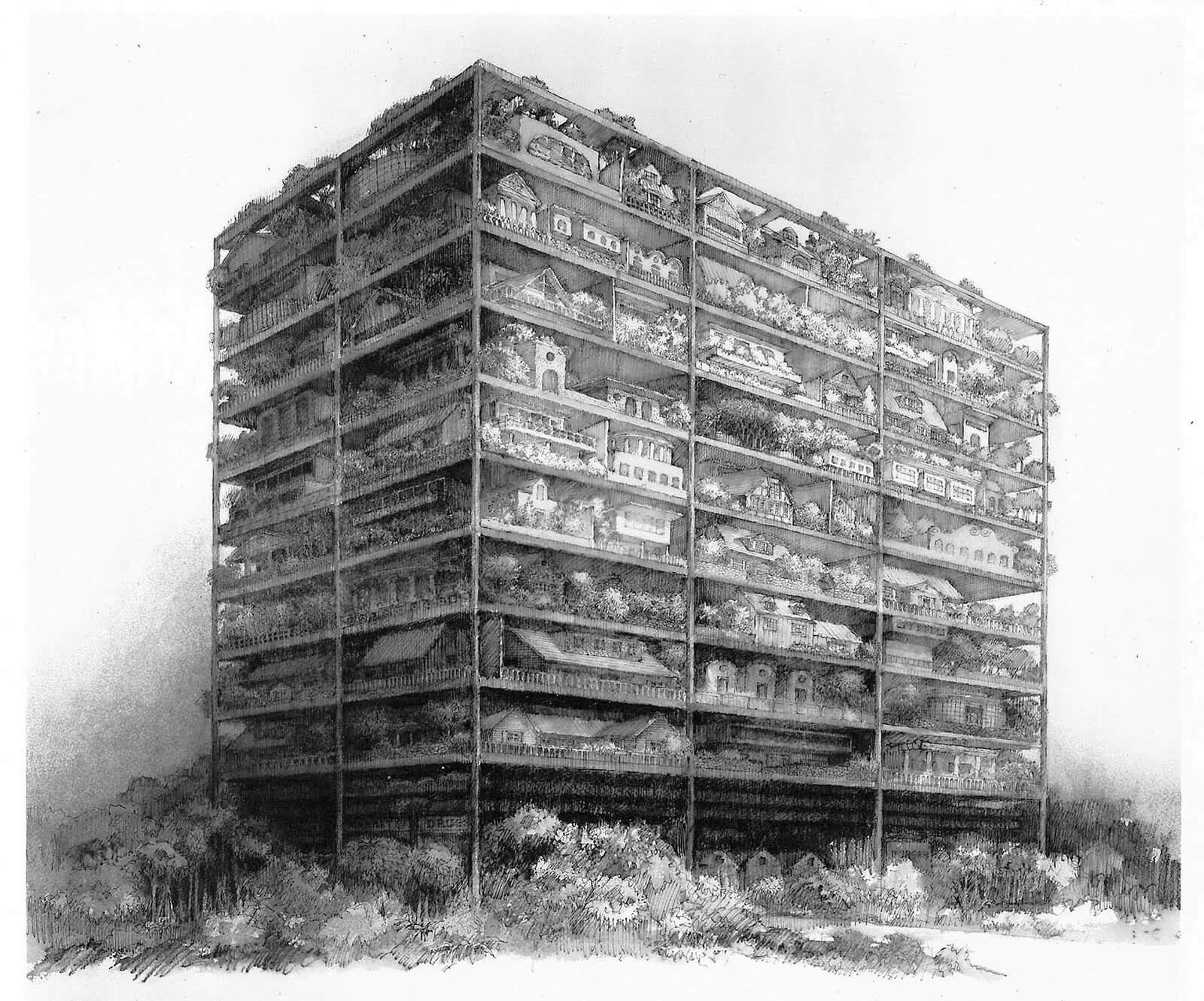

SITE’s one other project in the show is his iconic Highrise of Homes envisioned in 1981 for a dense urban area. The unbuilt design calls for an open cage-like structure with individual houses designed and built by the inhabitants according to their preferences. The houses are inserted into the grid where they sit on open floors and are covered by the next floor above, like scaffolding. As a result, the Highrise of Homes does not look like a solid anonymous building. It is rather an anti-building with a variety of individually expressed houses. Curiously, Wines’s seductive drawings convey a distinctly suburban character, as if slices of suburbia were stacked one on top of the other. Wines brought a rebellious attitude into the profession and expanded it by making buildings more artistic, imaginative, process-oriented, open-ended, integrated with nature, and fun. He treats architecture as a form of critique and a platform for continuous discourse.

There are too many other projects to mention in this review, let alone go into their essence. Their authors include Ant Farm, Serge Chermayeff, Eames Office, Richard Neutra, twin brothers Aladar and Victor Olgyay, Gaetano Pesce, Kevin Roche John Dinkenloo and Associates, Glen Small, and Eugene Tssui among others. Not everything in the show is reproduced in the catalogue and not everything that’s in the catalogue is in the show. There is a bit of competition between the two. The show could win by focusing more on the visuals, while the catalogue would improve by being more textual.

Let me touch on just a few more highlights. Arcosanti, an idealist and still ongoing self-built commune made up of organic-looking concrete ribbed domes, was started in 1969 by Italian-American architect, Paolo Soleri on an 800-acre-site, 70 miles north of Phoenix, Arizona. Building this romantic project attracted youngsters from all over the world. Its catchy marketing campaign said, “If you are truly concerned about the problems of pollution, waste, energy depletion, urban sprawl, water, air and biological conservation, poverty, segregation, intolerance, population containment, fear and disillusionment, purpose and priorities…join us!” One would want to examine some beautifully detailed drawings of this project; unfortunately, they only appear in the catalogue; several copies are available for reference in the gallery.

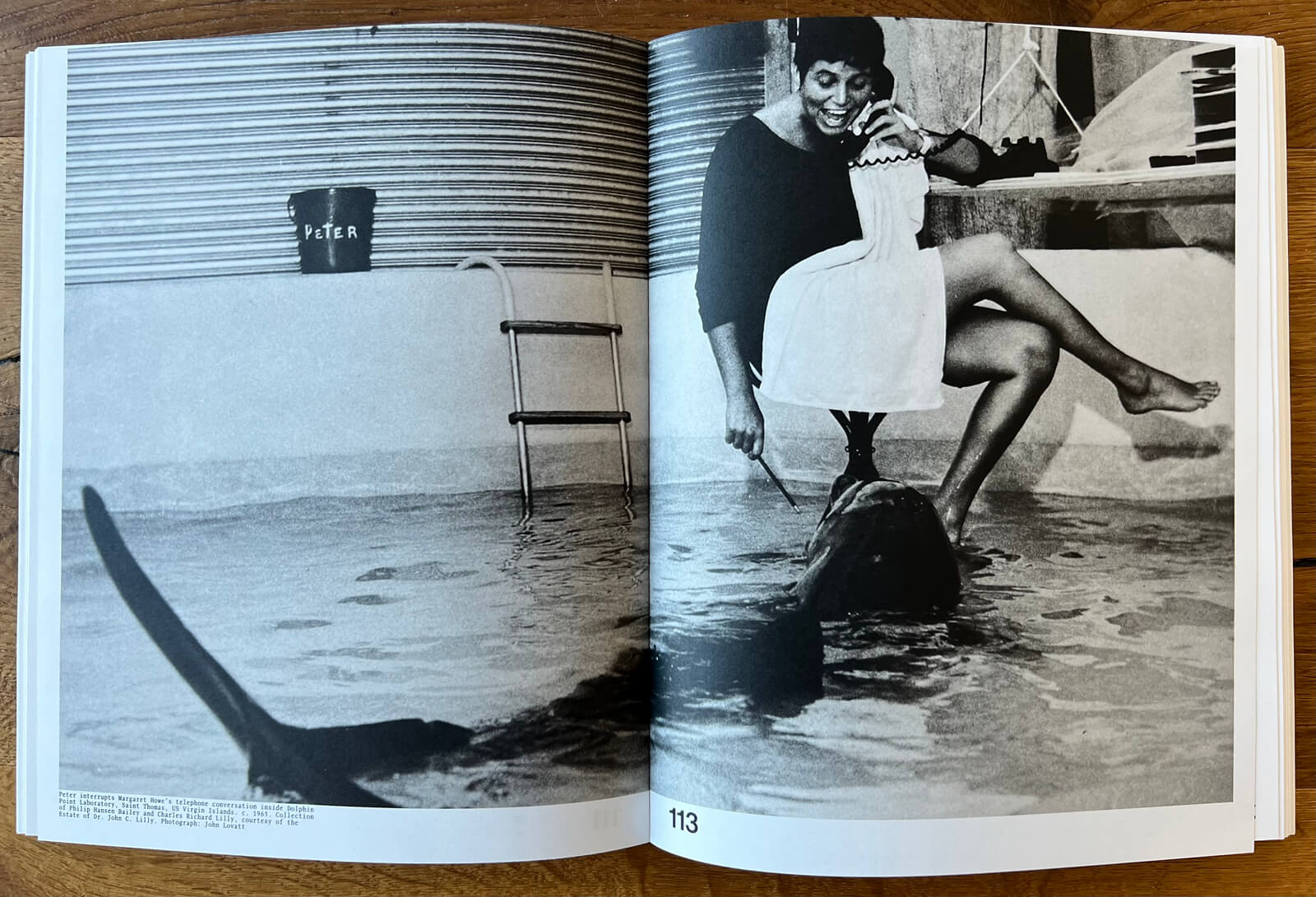

Unlike other projects that immerse themselves in greenery, Dolphin Point Laboratory sits directly over an ocean pool. Built in Saint Thomas, US Virgin Islands, in 1965, it was created by John Lilly, a neuroscientist and a pioneer in interspecies communication. A series of photos that look like they were taken during a science fiction film production show Margaret Howe Lovatt, a volunteer naturalist who embarked on a 10-week-long experimental cohabitation with dolphin, Peter. One of these photos captures the two eagerly engaged in a surreal scene when Peter stares at Margaret who sits playfully on a stool with her feet a few inches in the water, leaning over an office desk hung from above while holding a landline phone in one hand and a pencil in the other.

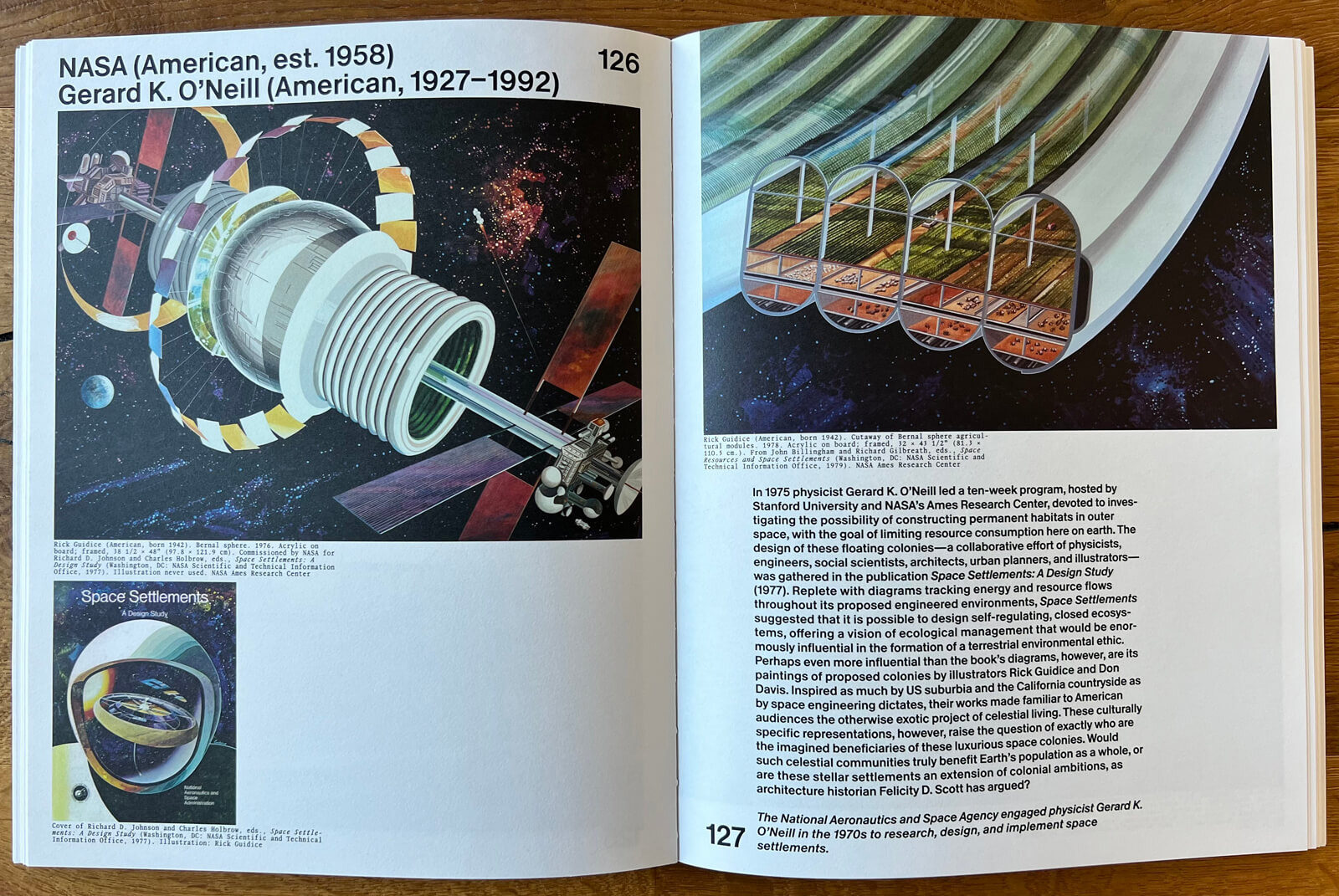

Even more otherworldly is a project imagined by physicist Gerard O’Neill with support from NASA and Stanford University. Called Bernal Sphere, it is a huge version of the International Space Station. The modular space colony was envisioned through futuristic drawings of illustrators Rick Guidice and Don Davis in the years between 1975 and 1978. They imagined the possibility of building space settlements that curiously evoke floating suburban agglomerations arranged into multilevel circular agricultural fields, gardens, and loops of sprawling conventionally-looking homes ready for future celestial habitation.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the word ecology comes from the Greek oikos, meaning household or home. It refers to the “study of the relationships between organisms and their environment,” which may be either organic, man-made, or hybrid. Therefore, the exhibition’s title, Emerging Ecologies directs our imagination to the vast potential of architecture’s relationship with nature, not as a proud sculptural thing soaring over the landscape, but as fully engaged and immersed in it. Ambasz once observed, “I strive for an urban future where one can open your door and walk out directly on a garden, regardless of how high your apartment may be.” Examples of such an optimistic future are not only emerging but already have been transforming cities around the world. Sensitive environments imaginatively and responsibly designed by such architects as Stefano Boeri, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Field Operations, Thomas Heatherwick, Christoph Ingenhoven, or WOHA allow us to take a peek into the kind of urban future that Ambasz was only contemplating at the outset of his exemplary career. I believe it is crucial for a modern museum to examine critically projects that are particularly being built today. MoMA’s show treats environmental architecture as a counterculture that flourished and died out. Except it didn’t! Acknowledging successfully built contemporary architecture that is eco-friendly is an important step toward turning a mere counterculture into what urgently needs to become mainstream.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Oct 25, 2023

What do you think?