Experiential chronicling: STIR reflects on impactful visits that widened perspectives

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Zeynep Rekkali JensenPublished on : Nov 08, 2024

In a world speeding toward the digital and disposable, the journey of æquō gallery began in Mumbai during the pandemic, led by two women sharing a vision. Tarini Jindal Handa and Florence Louisy met in Paris in 2019, an encounter that sparked an ambitious idea—creating and curating a space that celebrates India's powerful craft heritage internationally while redefining it through a contemporary lens. æquō, self-described as “India's first collectible design gallery”, was launched with a purpose beyond merely showcasing high-end designs. It aspires to create a dialogue between the ancestral and the modern, the Indian and the global, hoping to facilitate design, platforming India's rich craft legacy to be seen, celebrated and reimagined.

The founders believed Mumbai to be the ideal stage for this mission, with its multifaceted contrasts and delights. Handa has a family legacy and a vast personal experience in business, alongside a deep-rooted appreciation for India's traditional craftsmanship. Louisy, on the other hand, has an academic background from the famed Design Academy Eindhoven. She finds beauty in the quotidian, ranging from the simplicity of local metal plates to the intricate embroideries transforming plain fabrics into works of art. Together, they made an exceptional team with their combined sensibilities. They witnessed firsthand, the wealth of skill in India's smaller towns and villages and sought to align them with the world's most celebrated designers, aiming to bridge the technical and the poetic with an unsparing focus on craftsmanship.

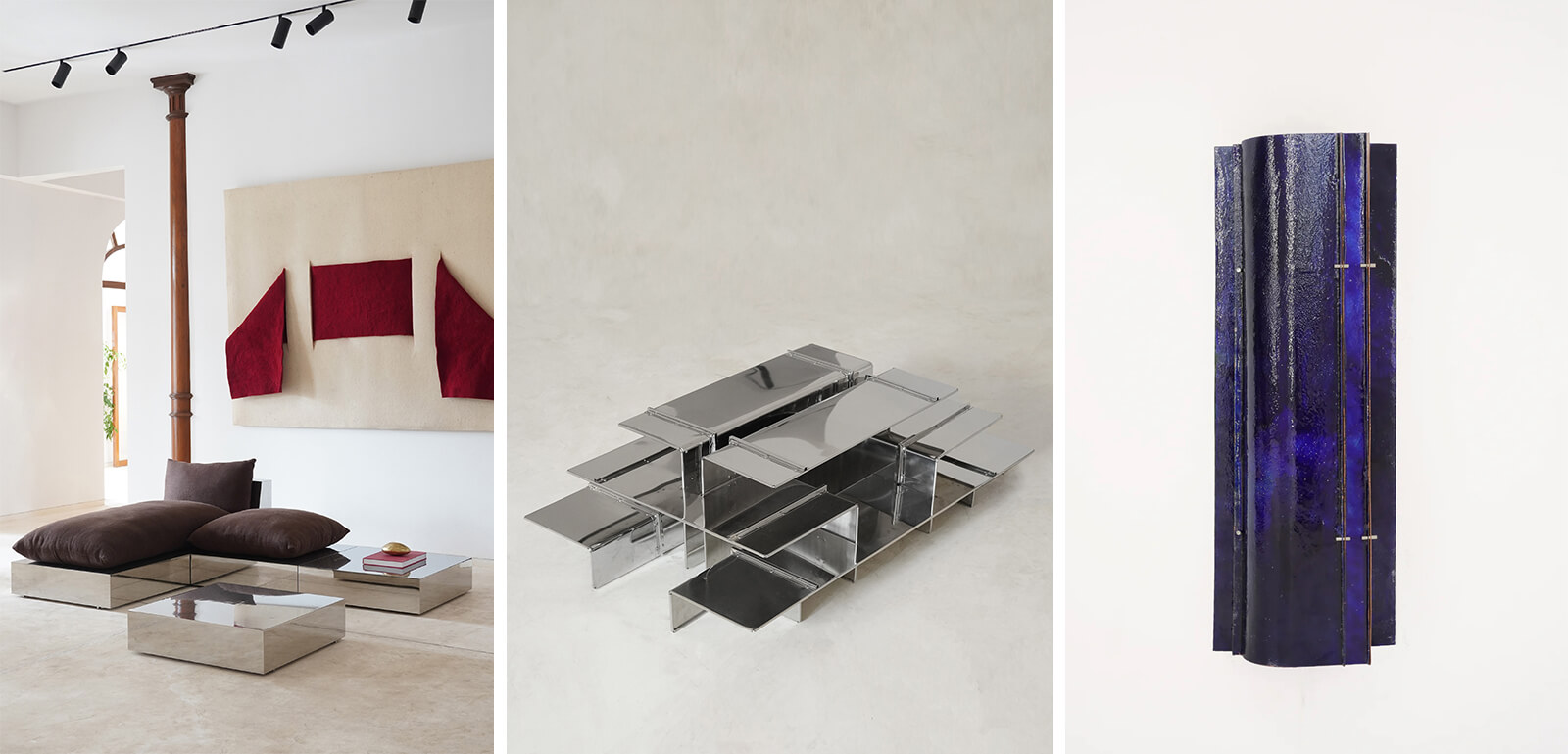

At PAD Paris and PAD London 2024, æquō unveiled a curated selection focused on India's craft heritage infused with an international sensibility. The presentations showcased collaborations that embodied the sophistication of contemporary design and the timeless beauty of raw, artisanal materials. The design exhibitions featured works from luminaries such as Humberto Campana of Estudio Campana, Kelly Wearstler, Linde Freya Tangelder of destroyers/builders and æquō's creative director Florence Louisy, who introduced her latest designs alongside Parisian designer Valériane Lazard.

Among the standout pieces was the Atuxuá cabinet by Humberto Campana, crafted from India's humble Sabai, highlighting the raw elegance and natural texture of the material. Tangelder's SLABS series consisting of furniture designs made of silver, teak wood and brass welds, cited the rugged landscapes of the Indian state of Karnataka as inspiration, where granite stone boulders merged into bold, layered forms, transforming fragments into a dynamic whole.

Adding to this lineup was the Pila Bidri screens, a collaboration between Louisy and French illustrator Boris Brucher, creating a reverie captured in metal and paying homage to the ancient Bidri metalwork tradition. Crafted in oxidised black metal with intricate silver inlay by master artisan Mohammed Abdul Rauf, these screens carry the weight of a centuries-old technique adapted to a contemporary, monumental scale. Brucher's freehand illustrations, sprawling across the screen panels, evoke an ethereal, almost cinematic experience as they unfold. His delicate lines traced in pure silver, relay quiet stories of Bidar's landscape, architecture and the intricacies of the Bidri craft itself. Echoing the symbolism found in Indian miniature paintings, the illustrations feel timeless and otherworldly, as if drawn from an ancient dreamscape.

I and Samta Nadeem, curatorial director of STIR, engaged in an insightful conversation with the founder and creative director of the æquō gallery, discussing its challenges and aspirations. Below are edited excerpts from the interview:

Zeynep Rekkali Jensen: I am eager to hear the story behind your decision to establish a collectible design gallery in India.

Tarini Jindal Handa: We are a land of makers. India is a country of the handmade, with craftspeople in every village, in every small town. Everywhere you look, people are creating things. They may not always be the most refined or highest-quality items, but there’s this inherent magic in our handicrafts. Being one of the most populous countries, we have a wealth of skill sets that many places don’t.

At first, we didn’t know if æquō would be a gallery. We simply wanted to see how we could push boundaries. I remember when Florence first moved to Mumbai, she bought the simplest stainless steel plates from the local market. I was surprised, but she saw something I didn’t—she saw the beauty in these everyday objects. There’s a special connection when the East meets the West. This experience sparked our journey, which began with the idea of giving India a voice in the international design scene. India has centuries-old crafts, dating back to the Mughal era and beyond. So we asked ourselves: how could it be that we didn’t have a contemporary design gallery here representing these incredible treasures?

As a gallery, we operate with openness and inclusivity. æquō doesn’t guard designs—we aspire to see the craft flourish [...] as it means more work and recognition for the craftspeople. – Tarini Jindal Handa, founder, æquō gallery

Zeynep: What impact do you hope æquō will have on the global perception of Indian craftsmanship? In relation, how do you envision your role in shaping the future of contemporary design in India?

Florence Louisy: As Tarini mentioned, there’s a kind of alchemy struck when people from different cultures come together. It opens up new perspectives, and each stage of this collaboration has enriched us. For instance, when we launched collections in India and later, abroad—in Europe, London and Miami—our goal was to offer a fresh, contemporary lens through which to view Indian craftsmanship.

Through our collaborations, we hope people rediscover traditional techniques that have been practised for hundreds of years. We don’t represent our designers, nor do we ‘lock them in’. If someone wishes to collaborate with the same workshop or artisans we’ve worked with, we welcome that. We aim to bring attention back to these crafts. While some craft traditions in India are well-established and thriving, others are more fragile and in need of support. These communities need nurturing and our collaborations at æquō aim to honour and uplift that invaluable heritage.

Zeynep: æquō strongly emphasises balancing the roles of designers and artisans in the creative process. How do you ensure that this equality is maintained throughout a collection’s development and what challenges have you encountered in this regard?

Florence: The balance between craftsmanship and design is central to what we do at æquō. Each collection starts with a focus on a specific Indian technique or craft. We research that craft, identify its uniqueness and then connect it with a designer who we feel aligns with its spirit and is open-minded in their approach. Sometimes, a designer approaches us with a pre-existing fascination for a particular craft, but the collaboration always begins with a deep dialogue with the artisans. We start by understanding their workshop’s tools, production capabilities and the nuances of the technique. Only then does the designer create within those constraints and opportunities?

Our process ensures that the craft guides the design, rather than starting with a concept and searching for a workshop to produce it. This respect for the technique preserves its authenticity, while the designer brings a fresh perspective. As a result, the final pieces often differ from the initial sketches, evolving organically through the interaction between the designer and artisan.

Tarini: As a gallery, we operate with openness and inclusivity. æquō doesn’t guard designs—we aspire to see the craft flourish, even if it means others build on what we’ve done. It’s gratifying for us when others follow suit as it means more work and recognition for the craftspeople.

One fascinating example is our collaboration with Paris-based designer Frédéric Imbert. He initially wanted to work with Dokra metal casting in Orissa, but after spending two weeks in the village, he was captivated by the raw material of Dokra—the wax resin used to mould the metal. His pieces evolved from this unorthodox approach, showcasing a more experimental side of Dokra while staying deeply rooted. Though the final product design looks vastly different from traditional Dokra, the craft’s authenticity remains intact, thanks to the close collaborations with the artisans.

Of course, not every designer can visit India in person; some work via our Bombay team who connect with artisans through virtual calls. Even without a shared language, design becomes the universal dialect binding them. Witnessing artisans and designers communicate through their drawings and concepts has been one of the most rewarding aspects of our journey.

Samta: Design interventions in a craft cluster are often driven by a sense of the 'greater good'—supporting crafts, keeping them relevant and providing sustained livelihoods for artisans—a charitable notion. Tarini, given your successful business background, is æquo such an endeavour or do you see it as a scalable, profit-driven gallery model?

Tarini: At its core, æquo is a business, aiming to make a mark in both India and internationally. Our goal is to be recognised alongside top collectible design galleries such as Galerie Kreo or Carpenters Workshop. We don’t want æquo to be viewed as a foundation.

We’re driven by a commitment to quality and Florence often plays a critical role here—if a piece doesn’t meet her high standards, she sends it back, pushing both designers and artisans to exceed expectations.

In India, there’s a tendency to settle for ‘good enough’ but Florence’s background from Eindhoven and her academic rigour ensures we keep pushing for excellence, reminding us we’re not done until it’s the best it can be. This focus on quality and innovation sets us apart and drives our ambition. We want æquo to stand among the world’s best galleries.

The gallery model [...] presents each piece with a story that gives voice to the craft, the raw materials and the techniques unique to India’s regions. It’s a space where people can take the time to understand what they’re buying—how each piece is tied to a tradition. – Florence Louisy, creative director, æquō

Florence: The gallery model felt like the perfect fit for æquo. It allows us to present each piece with a story that gives voice to the craft, the raw materials and the techniques unique to India’s regions. It’s a space where people can take the time to understand what they’re buying—how each piece is tied to a tradition. This connection is crucial because the transactional side sustains the relationships with our artisans and communities.

Zeynep: Florence, you juggle the roles of a designer and being æquo’s creative director. How do you navigate and find this balance? Relatedly, what inspired your latest works, like the sofa and tablet chair showcased at PAD London 2024?

Florence: My journey has been an organic one. When I first arrived in India, I was amazed by the techniques and raw materials I had never encountered before. As a designer, I had to experience these materials and methods firsthand to understand how they could be translated into design concepts for our gallery.

My collections often act as bridges to establish trust with a workshop. Once that connection is strengthened, we invite other designers to collaborate. This naturally developed into the gallery’s concept—from working with Indian crafts to realising that this could be a collective platform for more designers to engage with these incredible techniques.

Our recent pieces shown at PAD London reflect this journey. One standout was a sofa embroidered entirely by hand in Mumbai. Fabric is a significant part of India’s craft legacy, so creating our own embroidered fabric was both challenging and rewarding. The response in London was fantastic.

On the other hand, the Tavit chair design was one of the first pieces we created in Mumbai with a workshop that usually handles industrial motor parts. Over four years, we’ve developed a relationship with them, transitioning from small objects to larger furniture. The chair is a testament to that partnership, blending raw imperfections in bronze or aluminium with refined design. Each piece bears the hands and techniques of the artisans who crafted it, making it distinct.

Samta: How do you navigate concerns around appreciation vs appropriation when showcasing Indian design at global fairs such as PAD London or Design Miami? Given the audiences may be more familiar with designers like the Campana brothers, how do you ensure Indian craft is recognised?

Tarini: Storytelling is central to our approach. When we exhibit internationally, we make a deliberate effort to share the history and techniques behind each craft. For instance, we often display Bidri screens, a traditional Mughal craft and carry a book to every design fair to highlight these stories to our audience. We take the crafts we work with seriously and aim to create awareness beyond aesthetics.

Florence: Absolutely. This cultural exchange must be a genuine introduction to Indian crafts and not an act of appropriation. We are mindful of how fine that line can be, so we ensure each collaboration is mutual and built on respect. Our goal in exhibiting these pieces at international design events is to showcase the craft itself—its techniques, materials and its roots in Indian culture. Æquo is about more than the final product; it’s about spotlighting the craftsmanship and the stories behind each piece. We put immense effort into conceiving immersive shows, engaging with schools and organising events to introduce these crafts in a proper way that maintains cultural integrity.

Zeynep: With æquo debuting internationally this year, what excites you most about the future?

Florence: We’re particularly excited about our collaboration with Chamar Studio. This marks our first Indian partnership, involving Sudhir from the Dalit community. We’re working with recycled rubber from Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum. It’s a bold, impactful project that we’re proud to debut in Design Miami.

Originally, Chamar was a brand that focused on bags crafted from recycled rubber, but when we approached Sudhir, we sought to put the material front and centre. What started from a single blue chair evolved into a solo show with extraordinary, bold chairs highlighting this material. It’s been met with incredible enthusiasm in Mumbai and London and we can’t wait to share it with a new audience in Miami.

Æquō intends to facilitate the creation of meaningful designs that interfold the past with the present, bridging Eastern and Western influences. Tarini and Florence are deeply dedicated to the story behind each design, as reflected in their exhibitions and endeavours. Æquō, meaning ‘even’ or ‘equal’, aptly captures the gallery’s purpose—to create a level ground where Indian craftsmanship meets global design, resonating with their belief in the value of Indian craftsmanship and traditions of making. The designer collaborations in their roster show their passion for uplifting artisans and fostering cultural exchange. As they continue to build this dialogue, æquō stands poised to reshape global perspectives on Indian design.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 09, 2025

At the æquō gallery in Mumbai, a curated presentation of the luxury furniture brand’s signature pieces evokes the ambience of a Parisian apartment.

by Aarthi Mohan Oct 07, 2025

At Melbourne’s Incinerator Gallery, a travelling exhibition presents a series of immersive installations that reframe playgrounds as cultural spaces that belong to everyone.

by Asmita Singh Oct 04, 2025

Showcased during the London Design Festival 2025, the UnBroken group show rethought consumption through tenacious, inventive acts of repair and material transformation.

by Gautam Bhatia Oct 03, 2025

Indian architect Gautam Bhatia pens an unsettling premise for his upcoming exhibition, revealing a fractured tangibility where the violence of function meets the beauty of form.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Zeynep Rekkali Jensen | Published on : Nov 08, 2024

What do you think?