A London exhibition reflects on shared South Asian histories and splintered maps

by Samta NadeemJun 19, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dilpreet BhullarPublished on : Jan 28, 2024

Alana Hunt, a contemporary artist committed to addressing pressing issues and fostering dialogues, has emerged as a voice in the field of socially engaged art. Hunt's artistic journey has been marked by a deep-seated desire to create meaningful connections between art and the lived experiences of individuals, events and communities. For the last decade, she has lived in the Northwest of Australia, in Gija and Miriwoong countries, surrounded by diverse landscapes and indigenous cultures, which encouraged her to explore the complex interplay between colonisation, community and collaborations.

One of Hunt's underlying competencies is her seamless weaving of media forms including film, photography and printed matter with participatory practices. Her multidisciplinary approach allows her to navigate the nuanced layers of socio-political issues to offer a tapestry of knowledge systems for audiences to engage with. Hunt explains, “My starting point is not history so much, but the present—yet the present always pulls in history, like a thread unravelling.” The result is a body of work that is visually compelling but also intellectually stimulating, creating a moment to pause and ponder complex histories.

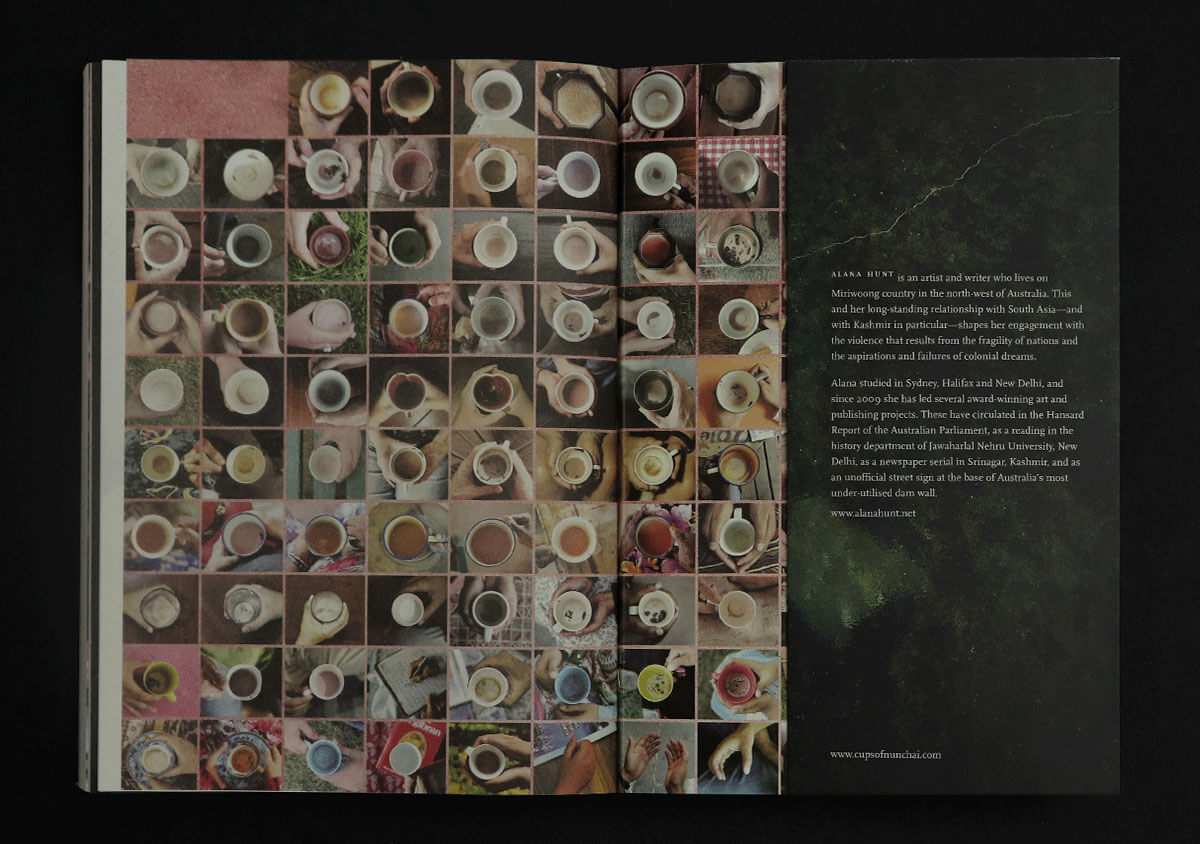

Central to Hunt's practice is her dedication to community collaboration. This ethos of engagement is exemplified by memorials like Cups of Nun Chai(2010-2020). Rooted in the events that took place in the summer of 2010 in Kashmir when over 118 people were killed by the state, this body of work embarks on a cross-cultural exploration, inviting people to share tea and conversation, in locations around the world, as a means of connecting diverse communities and fostering understanding among citizens across borders be it South Asia or Australia. The photographic documentation of the cups of nun chai (a salted tea with a tinge of pink served in Kashmir) and her recollections of these conversations were serialised in 86 editions of the newspaper Kashmir Reader across 2016-17 and later published by Yaarbal Books in 2020.

Grounded in the idea of interactive engagement with the populace, Hunt insists on creating a circuit of anti-colonialism from the lens of the Global South. The short video ROADS (2020) is a three-part repetition of a single scene taken from the 1998 TV mini-series Kings in Grass Castles—that involves an exchange between an Indigenous worker and an Irish settler of the Durack family who was among the first to colonise Miriwoong country. The video is part of an expanding collection of rescripted scenes from the movie that expose the violence and absurdity of colonial projects on stolen land. Overlooking the expanse of a yet-to-be-colonised landscape, the settler, alongside the Indigenous men, shares the advantages of developing roads. The conversation presents a lopsided view of civilisation and development. In doing so, the video is a commentary on colonial injustice carried out across empires.

In her latest exhibition Surveilling a Crime Scene at the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (December 5, 2022 – November 18, 2023), Hunt surveys the power dynamics of non-indigenous life in Miriwoong country, in the town of Kununurra and its vicinity. Represented through the exhibition and an eponymous film of 21:58 minutes, Surveilling a Crime Scene (2023), Hunt shines a critical light on the many forms of civil abuse by colonists in Miriwoong Country through tourism, development and the deceptively simple need for a home. The work revisits the fault lines of colonial modernities, to talk about how the events of displacement and dispossession are not historic but enacted and re-enacted over and again, through daily life in a settler colony like Australia.

Dilpreet Bhullar: Your art practice is deeply, and more importantly, rooted in the difficult histories of not only Australia but also India, of our times. What made you approach these subjects in your creative process?

Alana Hunt: It might sound odd, but people who know me well will recognise that my practice is not so much a series of “subjects”, but more reflective of the course of my life. Places in Australia and South Asia have been anchor points, and currents across these places, push and pull.

My starting point is not history, but the present—yet the present always pulls in history, like a thread unravelling. And I seem to follow it.

Dilpreet: The projects be: Cups of nun chai, Paper txt msgs from Kashmir, and Surveilling a Crime Scene, which involve community engagement. How do you navigate the complexities of representing experiences and histories while involving the communities directly affected?

Alana: I don’t like rules or formulas; art should be anarchic and rigorous. How I work is grounded in aspects of my life that are personal and precise—and a sense of accountability to people I care about is vital. Though none of this is stable, but an ongoing process. Where a body of work begins and ends is never really very clear to me, and after beating myself up about that for a while, I now feel it is okay. I am very interested in time, both as a durational process of brewing or fermentation of the work and also the particular moments in time a work encounters.

Each work is distinct. Paper txt msgs from Kashmir (2009 - 11) was, in one sense, about creating a frame that other people filled and mobilising those responses as a means of countering the government’s reasoning for the pre-paid phone ban in late 2009, and the Indian public’s lack of outrage. Cups of nun chai (2010 - 2020) was more about dialogue accumulating against the state’s accumulative killing and in that context making a record not only of current events and history but of things that might appear small or obscure but felt important to hold on to at that time. Coming from the guts Surveilling a Crime Scene (2023) feels like a metabolising of my life over the last decade in this part of Australia. It is an attempt to articulate that colonisation is not some grand historical event but intimately wrapped up in the violence of settler daily life.

What is consistent is this impetus to make more legible specific violence that is obscure or has been obscured; to ensure the works circulate effectively with particular publics, and all my works are always made by bouncing ideas and possibilities around with a constellation of people—people I really treasure. I don’t make work in isolation.

Dilpreet: Coming to your recent video work Surveilling a Crime Scene, how does your art explore the intersection between settler colonisation, Indigenous history and surveillance practices?

Alana: In Australia, First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) people are disproportionately criminalised while the settler society fails to recognise their own crimes. Surveilling a Crime Scene flips this by placing non-indigenous life at the heart of the crime scene.

The film is about the materialisation of non-indigenous life in Miriwoong Country, near the town of Kununurra and its surroundings. It is about settler colonialism, not in a historical sense, but in how it functions right now. Over the last few years in Kununurra, and across many remote and regional towns in other parts of Australia, there has been so much talk about stolen cars and very little talk about stolen country. And surveillance cameras have proliferated in Kununurra as a result.

I am not telling an “Indigenous history”—in fact, I try hard not to. I try to keep my focus as a non-indigenous person on non-indigenous culture. This film is a mirror asking non-indigenous people to take a look at the cogs of our daily lives that keep the settler colony in motion. Non-indigenous people commonly photograph Indigenous people. I want to turn the lens onto non-Indigenous life. I am interested in the unease this may incite.

Dilpreet: Connection to home and Indigenous perspectives on land are two salient features of your practice. How does the concept of surveillance impact the relationship between Indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands?

Alana: It is common for non-Indigenous people in Australia to think of First Nations people’s “ancestral lands” as being somewhere else. Not in the suburbs, or the cities. But some abstract place in the “outback”. In truth, every home on this continent is built on someone else’s stolen ancestral land. This is the inherent crime, the inherent injustice—that is just never reckoned with.

Colonisation stole and then reordered the land. Slicing it, fencing it, redistributing it and controlling it. At a local level, in the Kimberley region, today that can mean heavy locks and security cameras at gates to cattle stations, the management of land through national parks, the assertion of private property, the dominance of non-indigenous bodies in particular spaces, and the ecological shifts caused by development. But surveillance also permeates the way Indigenous people are watched in public. In some small way, in this film, I wanted to shift that sense of being watched onto non-indigenous people, as though surveilling a crime scene.

Dilpreet: How do you see art and creative practices contributing to discussions around Indigenous sovereignty and reclaiming narratives in the face of historical and contemporary surveillance practices?

Alana: Art is vital. Absolutely. But as the academics Eve Tuck and K Wayne Yang have said: Decolonisation is not a metaphor. I always keep that sentiment close to my heart.

Dilpreet: As an artist, you have paid acute attention to letting the audience witness how the circuits of colonial injustice and economic exploitation are perpetuated in new forms in the countries that have achieved liberation after long years of political struggle. The act of solidarity across countries, irrespective of the geographical distance, is extremely crucial to your work. Could you elaborate on this?

Alana: I suppose here, you are referring specifically to my work in Kashmir, and India’s control of that region after the British left and the conversations that took place about that within Australia through Cups of nun chai? I don’t see Australia as having achieved liberation. Here, the colony continues. And so do resistances to it.

But certainly, my experiences in Australia and South Asia, inform each other profoundly. Surveilling a Crime Scene features a mountain that is blown up to make a large dam to feed the Ord River Irrigation Scheme and expand colonial life. Of course, the struggles in the Narmada Valley and the damming of particular parts of the Jhelum River in Kashmir are with me when I am sitting at Lake Argyle in Miriwoong Country in the North West of Australia. The seeds of this dam (in a very remote part of Australia) were planted by the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonisation, which draws in Palestine. And those people in Australia who worked on the irrigation scheme made research trips to investigate big dams in South Asia. There are so many points of connection. The entitled tourists who flock to waterfalls here, remind me of Indians in Kashmir riding shikaras on the Dal Lake or sliding on the snow at Gulmarg. While these things are not stated explicitly in my film, they fuel my work as currents—between these places—pushing and pulling. Churning our world.

Dilpreet: The printed books as the tangible documentation of your practices and processes make the artwork accessible to a wider public, and significantly enter a novel way of looking at it, unlike in a white cube. As an artist how does the art of publication push for a shift in the way of looking at an artwork?

Alana: I am really interested in circulation—and by that I mean the movement of my work in the world. Publications are wonderful. They enable a work to live longer than the period of a conventional exhibition. They allow a work to circulate to more diverse publics and more obscure places. There is a tangibility to them, that is intimate and engrossing. While bookmaking can be an expensive enterprise, there are ways of publishing that need not be expensive—photocopies, PDFs and existing media platforms like a TV station or newspaper or a radio broadcast.

One reason I came to make Surveilling a Crime Scene in the form of a film, was the potential for circulation that a film enables. There are no freight or storage costs. But the linearity of the film also captures an audience for a particular period, for a particular journey.

I made the film into a book because I hoped some people might want to take the film home and flick through the pages—moving at their own speed. Long ago I’d seen Marguerite Duras’ script of Director Alain Resnais’ film Hiroshima, Mon Amour rendered into a book alongside stills of the film. In some ways it enables the reader, to remake many versions of the film for themselves. I treasured that book more than I treasured the film. I could linger on every one of Marguerite’s carefully sculpted words.

Dilpreet: The visual language—repetition of cups and hand gestures in Cups of nun chai, flat and grainy surface of cinematic scenes from Surveilling a Crime Scene, gravitates toward textual narrative in the former and spoken words in the latter. As a witness, I would like to know how you arrive at the point of conclusion if "a" particular visual taxonomy would complement your narrative.

Alana: Intuition is a big part of my practice and an understated aspect of art-making in general. But there needs to be rigour, research and experience alongside it.

In 2017, I was denied permission to use some archival images in an exhibition from the local historical society. They were concerned I would make a “myth out of their history”. As though their version of history was not the biggest myth of all. This refusal only prompted me to restage the archival images myself. All my photographic work since has been shot on 35mm film.

Drawing on the aesthetics of the past, while photographing the present, I am trying to collapse the distance between the past and present to illustrate colonisation as a continuum.

There is a home movie nostalgia to the super 8mm film format—building an implicit naivety I wanted this film to slice through. As James Baldwin wrote in The Fire Next Time:"It is the innocence which constitutes the crime."

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dilpreet Bhullar | Published on : Jan 28, 2024

What do you think?