Atelier Tropical House: A multi-use structure reflective of Bogotán building traditions

by Almas SadiqueJan 18, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dhwani ShanghviPublished on : May 17, 2025

In 1898, when Ebenezer Howard proposed the Garden City model as a solution to the social and environmental problems in England wrought by rapid industrialisation, he envisioned purpose-built, self-contained towns on undeveloped greenfield land, distanced from the overcrowded industrial city. The economic model underpinning this vision was centred on the idea of collective land ownership held in trust by the local community and its increasing value, generated through development and population growth, would be reinvested locally in public services, infrastructure and housing. Designed to create a self-sustaining city, Howard’s model aimed to curb land speculation by making residents stakeholders and ensuring that the profits from urban growth were redirected from private landlords to serve the collective good.

London's housing crisis today is shaped by a set of urban and spatial pressures distinct from those that shaped Howard’s vision. Today, the city grapples with a desperate need for housing and the competing demand for industrial land. Inflated rents across the capital city, along with the resultant pressure on small businesses and a shrinking economic diversity has effectuated significant shifts in planning policy; most notably through Policy E7 of the 2021 London Plan, which advocated for the co-location of industrial and residential design within a single site. Marking a departure from the somewhat rigid zoning logic of the Garden City model, co-location instead adopts a dense, complex, mixed-use urbanism, encouraging all boroughs to explore the potential to intensify industrial activities on existing sites.

Wick Lane, a co-location scheme located in the historic manufacturing district of Hackney Wick, stands as a contemporary response to London’s ever-evolving demands of meaningful urban space. Once home to industries involving printing inks, rubber works and plastics, the area witnessed a gradual shift with deindustrialisation in the late 20th century, attracting artists and creatives who repurposed disused factories into studios. The 2012 London Olympics catalysed further transformation, with infrastructural investments and regeneration strategies repositioning the area as a key redevelopment site.

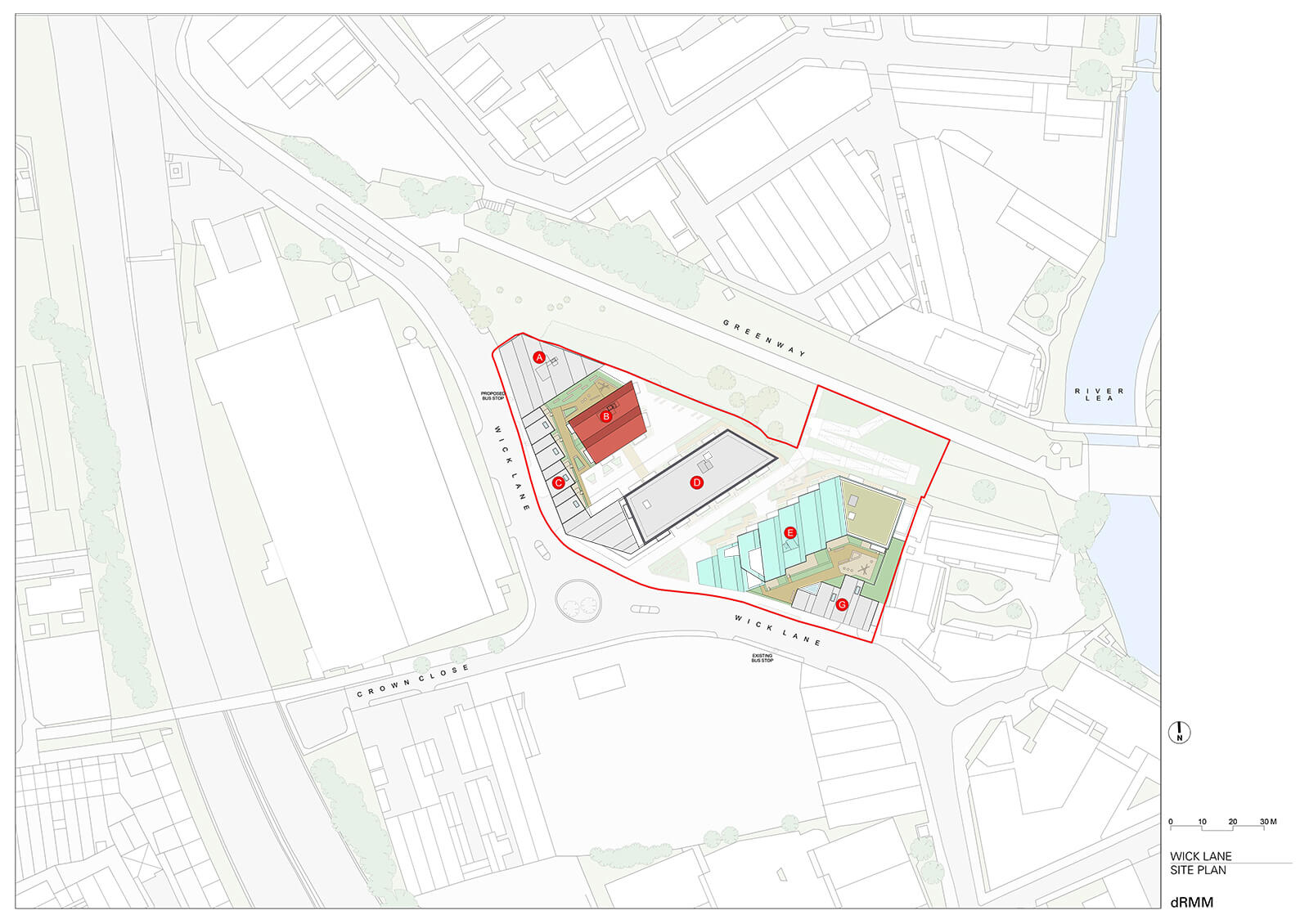

The Wick Lane site—formerly occupied by an MDF workshop, artist studios and a car rental lot—embodies a striking duality. To the north lies the Fish Island and White Post Lane Conservation Area, where Victorian-era brick architecture and mid-century modern warehouses now accommodate a mix of industrial, creative and residential uses. To the south, however, the rigid boundaries of Strategic Industrial Land (SIL) remain firmly off-limits to redevelopment. The Greenway—a foot and cycle path following the course of Bazalgette's Northern Outfall Sewer—skirts the site's edges to the north, linking it to Victoria Park in the west and the Royal Docks in the east.

dRMM Architects, long embedded in the area’s evolution, were instrumental in shaping the vision for Wick Lane. Their involvement began in 2013 when they co-authored the London Legacy Development Corporation’s (LLDC) Design and Planning Guidance for Hackney Wick and Fish Island—a document that laid the groundwork for safeguarding heritage assets while accommodating future growth. This familiarity with the site’s layered character later informed their approach to the Wick Lane project, even as the asset changed hands during planning.

Wick Lane presents a compact cluster of five buildings arranged to accommodate 175 homes and 2,250 square metres of commercial space. The mixed-use development meets two key planning conditions set in place by the LLDC: the retention of commercial and light industrial floor space and the safeguarding of the Strategic Industrial Land (SIL) to its immediate south. The masterplan navigates these constraints through a dense composition of residential, commercial and industrial programmes, with buildings oriented to place the latter along the southern edge, creating a buffer between the residential buildings and the adjacent traffic and industrial activity. A Thames Water sewer head on site further restricts buildable ground, leading to a fragmented layout that simultaneously retains existing cycle routes.

The seemingly incremental disposition of the cluster of buildings seems to echo the stratified material heritage of Hackney Wick. This sense of temporal layering is reinforced by a disciplined material logic: each building adopts a singular palette—comprising red brick, black brick, corrugated steel, ribbed blockwork, or cast glass—that wraps across its walls, roofs and soffits, creating strong individual identities while retaining a collective coherence and lending a graphic clarity as if each building were a distinct typology within a broader taxonomy of industrial architecture.

The commercial units line the edge of the main road, creating an active street front with a mix of shopfronts, studios and double-height workshops that reintroduce the kind of maker spaces displaced by earlier redevelopment. Operated by Tradestars, a platform that supports independent and local enterprises and fitted out in collaboration with Sophie Franks Designs, the spaces now accommodate a range of tenants—from tattoo parlours and textile studios to bike repair shops and salons. Materials like ribbed blockwork, cast glass and concrete distinguish the commercial base, marking a visual distinction between the workspaces and the housing above. The residential buildings express the disciplined material language with red brick, black brick or corrugated steel façades and balconies in steel and glass, either inset or projecting. At street level, roller shutters gesture to the industrial character, while the upper levels remain more reserved. The development meets the street without gates or walls, creating a porous edge where buildings open directly onto the pavement. The transparent façades and open thresholds encourage visibility and informal exchange, allowing the scheme to blend into the rhythm of Hackney Wick.

A holistic landscape design scheme by Grant Associates reinforces this openness. Wick Walk and The Yard—two main public routes—cut through the site, defined by soft planting, while pocket gardens, communal terraces and a new pedestrian and cycle link connect to the Greenway, extending the public realm through and beyond the site. What was once a fragmented industrial plot is now reconnected, both spatially and programmatically, to the wider urban fabric of Hackney Wick.

Wick Lane offers a carefully designed repose from the lofty but dubious aspirations of 20th-century urban planning—rejecting the rigid zoning, spatial segregation and oft-contested alienating environments of both post-war estates and sprawling suburbs. It attempts to collapse the divide between work and home, proposing an urban life where living, making and socialising coexist within a shared framework. Yet, beneath its integrated architecture lies an economic model not unlike the one that eventually overtook the Garden Cities, much like Howard’s Letchworth and Welwyn in Hertfordshire, whose utopian ideals eventually came undone under market pressures. While Wick Lane presents itself as an antidote to “beds above sheds” developments, it is, for now, tethered to systems of private land ownership and centralised control—developer-led, speculative and structurally top-down. In doing so, it still reflects a broader tension in contemporary planning between spatial innovation and the enduring realities of land speculation and economic exclusion.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dhwani Shanghvi | Published on : May 17, 2025

What do you think?