Bangkok Tokyo Architecture on challenging singular authorship through flexibility

by Mrinmayee BhootAug 22, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Jul 05, 2024

In the preface to Agonistic Assemblies, a book that explores the socio-political dimension of urban design edited by Markus Miessen, Chantal Mouffe brings up agonism as a model of democracy. It immediately brought to my mind the recently concluded elections in India and the coalition government formed as a result. One would hope—like most liberals in the country—that opposing forces in this coalition would give rise to, as Mouffe explains, “A well-functioning democracy…where an agonistic confrontation of democratic political positions can take place.” The hope is still naïve, born from the dread that many in the country and all over the world have held, over the death of democracy: the decline in spaces and voices of dissent, guarantees of free and fair elections, the rights of minorities, freedom of the press and the rule of law. While Miessen postulates in his introduction, “Democracy is always in the making. It should be understood as a verb, an activity: a practice of moving toward democracy. And this practice needs to be nurtured every day.” There is some form of hope in this statement.

Conflict in pluralist democratic societies cannot and should not be eradicated, since their specificity is precisely the recognition and the legitimation of conflict. What pluralist, liberal democratic politics requires is that others are not seen as enemies to be destroyed, but as adversaries whose ideas would be fought, even fiercely, but whose right to defend those ideas will never be put into question. – Chantal Mouffe, Democracy as Agonistic Pluralism

The book buoys this hope by asking through its texts: How do we revive democracy, inculcate a spirit and atmosphere of participation and what does space have to do with it? It is, after all, a public space where people can assemble and voice themselves, indicative of a healthy democracy. Delving into the politics of assemblies, important questions about publics, democratic institutions and space can be asked: What influence do spaces have in creating publics? How do (public) spaces cultivate society? What spaces can we design to serve as platforms for change?

In a world undergoing what Miessen terms a ‘socio-ecological transition’—and what really is discontent over the inequalities we face—these questions become even more urgent. We need to ‘promote an understanding of the community that is built upon communication and shared practices, a practice-based and informal means of (public) institution building’; essentially a grassroots approach as the book will go on to illustrate.

Miessen notes that, rather than being a historical overview of what assembly practices have been and what they have meant, the book instead provides a toolbox; a consideration of what could be possible in terms of architectural thinking as a method. Miessen elaborates, “As an anthology, this book presents work on cultures of assembly. It stresses the relevance of small-scale and decentralised spatial formats of local knowledge production to community building and embedded political decision-making.”

In order to facilitate this, the texts in the book look at spatial proximity as ‘a tool to mediate between the individual, the collective, the neighbourhood, the city, the state and society at large’. What’s most crucial, especially today as we see formal institutions break down or bear down on their citizens is they offer a reflection on informal institution building and a look at sovereign spaces of exchange that can empower people by facilitating interactions.

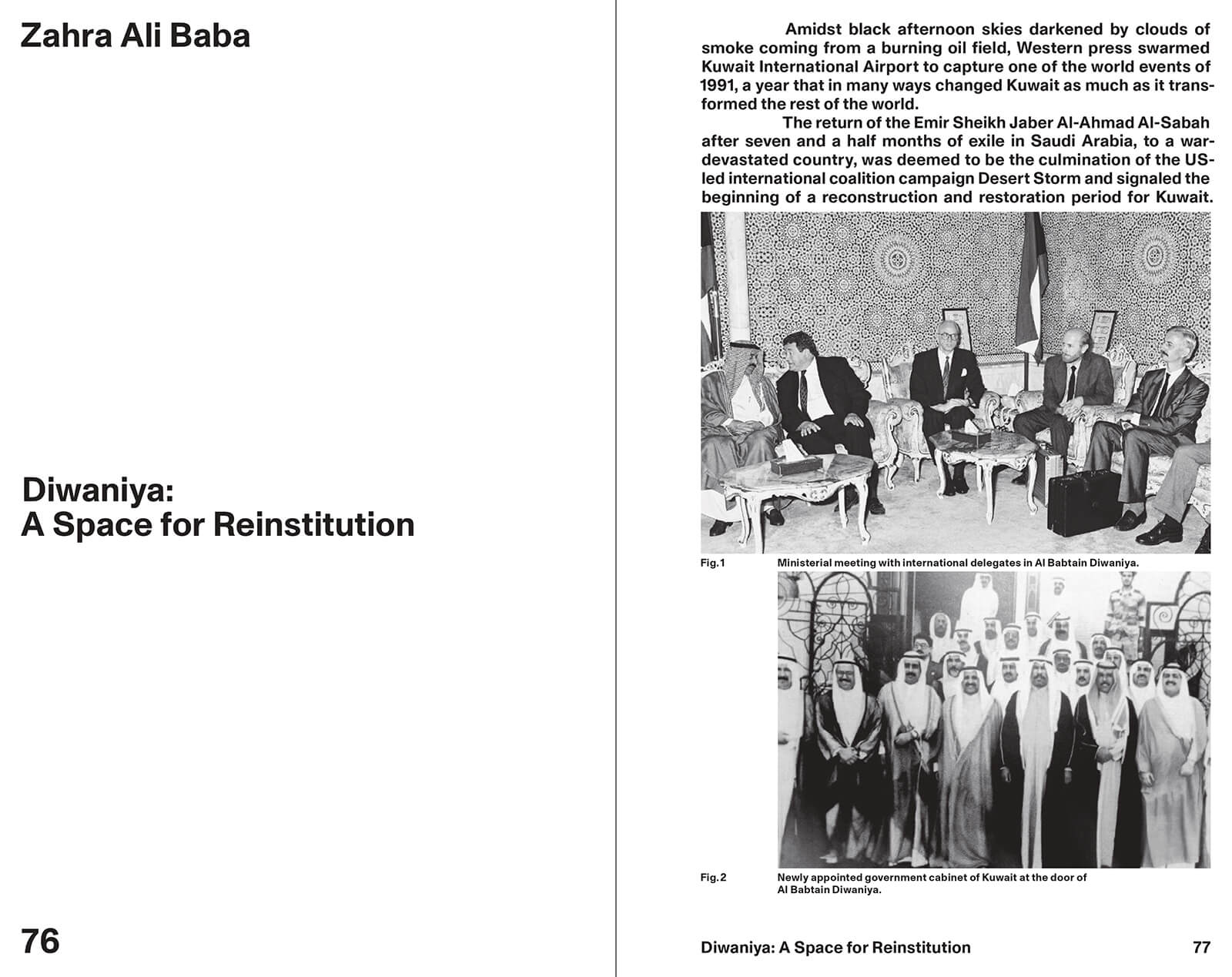

In his introduction, Miessen pulls at several threads in his own work on the architectures of participation and their bearing on society. The one that seems to hold the book together is the idea of cultures of assembly and diwaniya–‘[a] distributed urban form of para-institutional assembly’ prevalent in the Kuwaiti cultural and social landscape–as indicative of this culture. He details an ongoing research trajectory which started during a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) fellowship, Cultures of Assembly in collaboration with Joseph Grima in 2010. One of the starting points and focuses of the study was the diwaniya. Hence, as he details, the second cluster of texts–the first being the preface and introduction–focuses on the landscape of Kuwait and diwaniya as a practice/space which becomes one of the possibilities of assembly.

[Diwaniya] presents a showcase of an alternative that attempts to imagine a model of a (more) solidary city. On the scale of a city and, in fact, small country, it interrogates how societies can learn from and produce alternative formats of physical exchange, working toward realistic scenarios in which decentralised decision-making meets spatial justice. – Markus Miessen, Proximities

Through the central hypothesis of the diwaniya or “its potential status as an abstract and analogical role model for not only other geographies, but its particular relevance as a community hub in the context of the ongoing and soon-to-intensify global phenomenon of the socio-ecological transition,” the argument is that individual and collective action or distributed assembly and proximity should be core attributes to consider in producing the contemporary and future city. While Miessen details many interconnected threads on the role of para-institutions in this regard, I could not help but keep going back to the agonistic model, not just in the context of coalitions, but of ongoing protests around the world. My mind kept turning to the students currently protesting the genocide in Palestine, about the protests of 2019/20 against the CAA and NRC Acts, and imagining the spaces and knowledge(s) they produced. While these form part of the main argument, they seem understated in deference to the book’s preoccupation with the philosophy of politics and space. Still, a crucial question the book asks: what does (and should) participation look like in a “true democracy”?

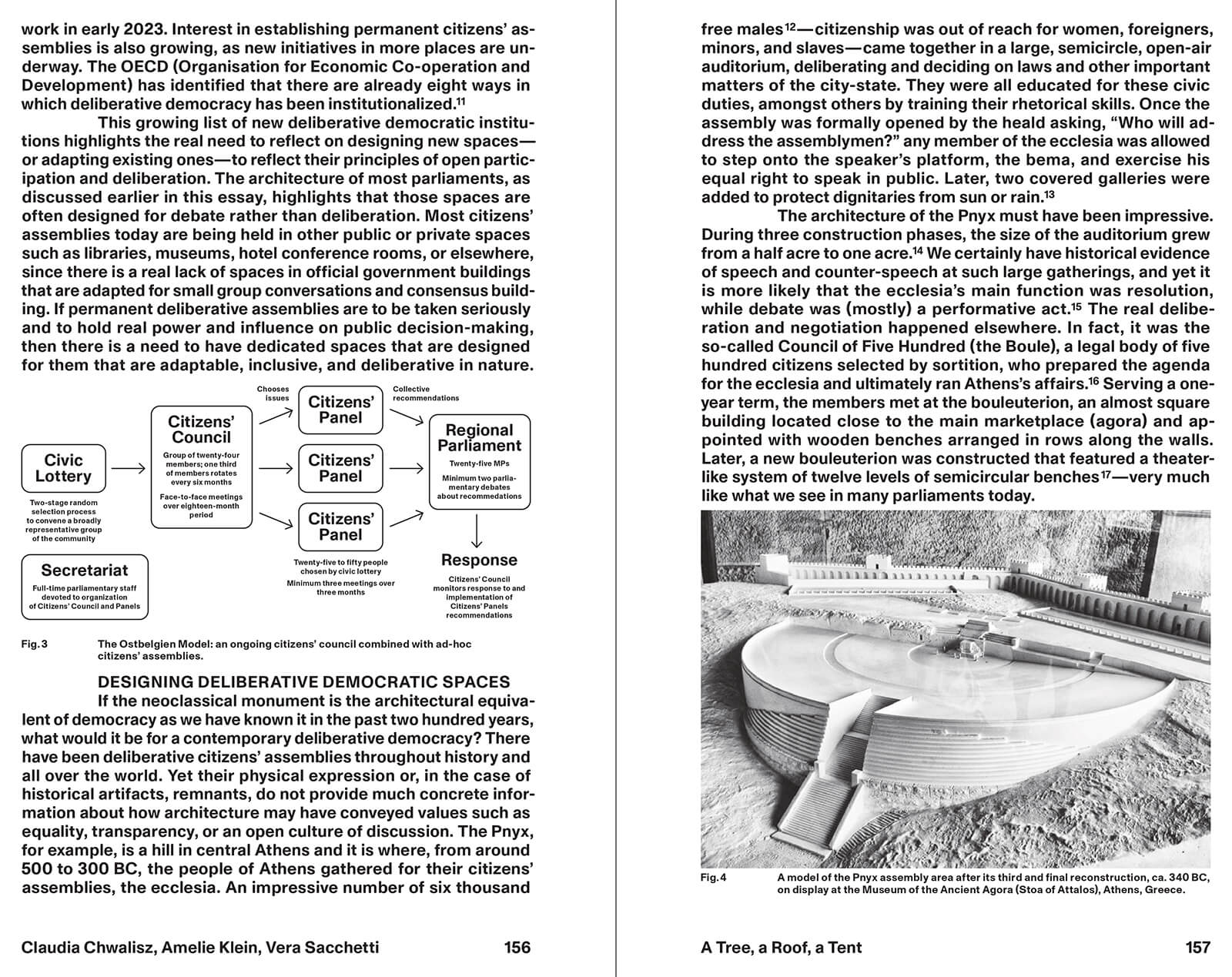

Divided into different clusters with the second as discussed above setting the conceptual undertones of the anthology and the third delving into the themes of assembly, local communities and publics. Of all the texts in this section, one of the most insightful is “A Tree, a Roof, a Tent: Spatial Models for a New Democratic Paradigm” by Claudia Chwalisz, Amelie Klein, and Vera Sacchetti where they suggest that we do not face a crisis of democracy but one of “elected oligarchy.” The text interrogates ‘public’ architectures of existing governance systems and suggests alternatives “that reflect genuinely democratic principles of openness, participation, and deliberation.”

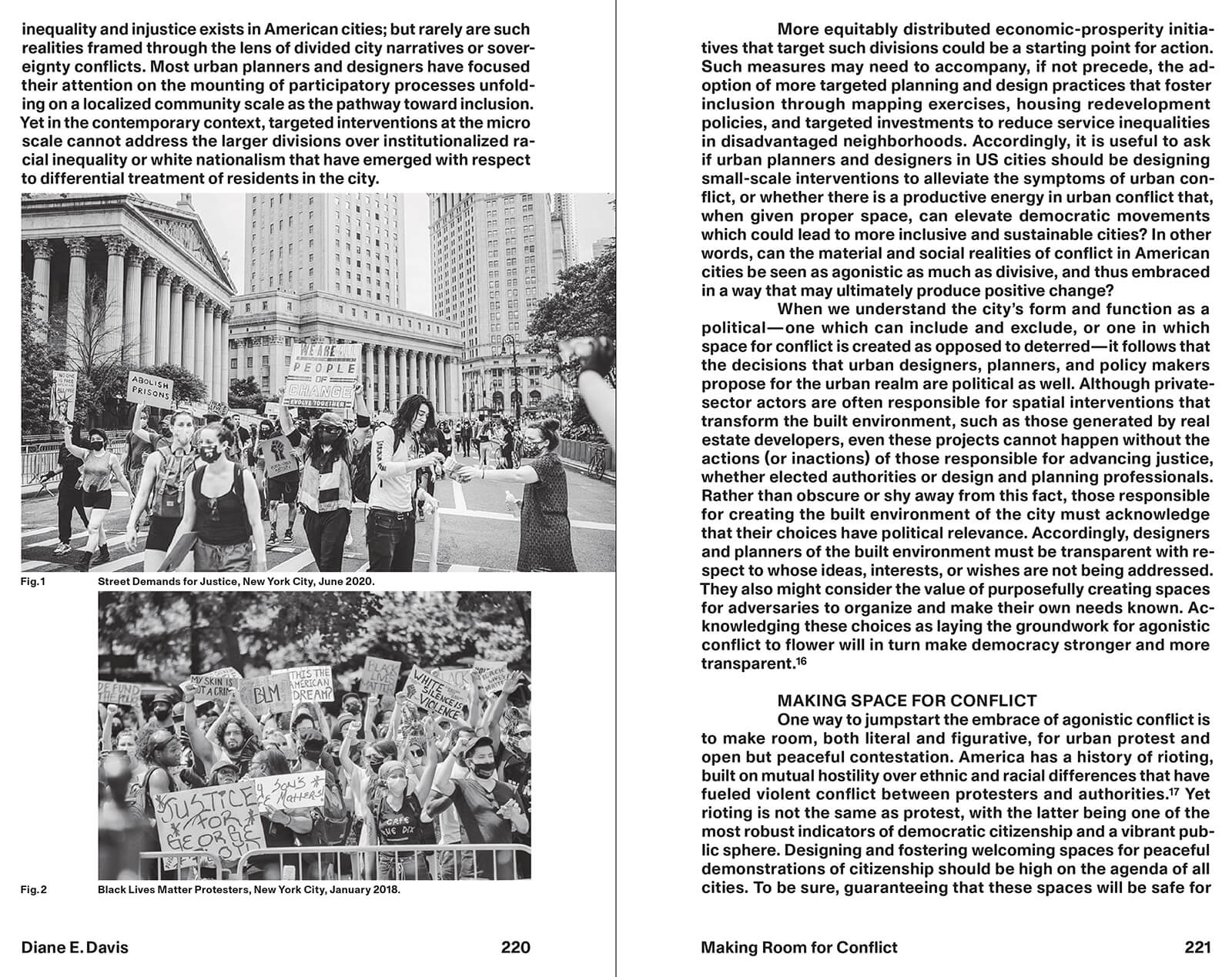

In the chapter, they detail how space shapes behaviour and how it can lead to better deliberation, especially in the case of assemblies. The focus on public space also allows them to dwell on the idea of protests and that the simple gesture of sitting could in itself offer clues for a new deliberative spatial model. Thinking along similar lines but expanded from the architectural to the urban, Diane E. Davis’s essay Making Room for Conflict focuses on the conflict to ask if we can conceive of public space as a site for it. She questions if conflict can become a productive force in imagining new forms of spatial agency.

She writes, “It is the city where acts of citizenship—defined in terms of political rights and responsibilities associated with belonging to a given political community—are increasingly unfolding” and urges planners and designers to consciously include spaces for protest (for according to her, protests are indicators of a vibrant public sphere). Further, on the topic of conflicts and how they might shape our future, Rahel Süß adds an interesting dimension to the role of social conflict in the context of new democratic experiments. In How the Politics of Provocation Is Shaping Democratic Futures, Süß hopes to show how provocation can revitalise democracy.

What’s most interesting about Süß’s text is that she reminds us that provocations have throughout history deepened the promise of democracy, for instance, the abolition of slavery, workers’ rights and women’s right to vote, all the result of provocations. Moreover, as she writes, a provocative model discards the assumptions that markets or companies with vested interests can ever provide solutions to pressing issues of our time. Most vitally she notes, “The politics of provocation rejects the idea that political subjects emerge from a mere citizen status or by casting a vote” since historically, this very idea has been continuously challenged. Significantly, the contributions don’t see protests as inherently disruptive but as a form of assertion and inclusive participation. After all, it is in the porous space of protests that we may ask: what else could be possible? How might we be seen?

Going back to the introduction, Miessen brings up another book written by Mouffe, Towards a Green Democratic Revolution: Left Populism and the Power of Affects (2022). In the book, Mouffe argues that to design meaningful institutions, one must consider the forms of identification to such that are available to democratic citizens. She explains that “an approach privileging rationality leaves aside the crucial role played by passions and affects in securing allegiance to democratic values.” Essentially, Miessen highlights the affective dimension of space and the importance of an urban scale and proximity to which a local inhabitant and user can relate, which in turn does decide their status as citizens.

As pointed out, the affect of proximity and to what scales people can relate is crucial, which leads us to consider decentralisation as a way of formulating new typologies of participation. In what is perhaps the most radical choice of text for the book, an interview with Italian architect and public intellectual Giancarlo de Carlo, led by Ole Bouman and Roemer van Toorn in October 1987, Architecture Is Too Important to Leave to the Architects presents De Carlo’s views on society and governance and what he believes is the affective dimension in architecture. The interview highlights the book’s preoccupation with design as being able to actively form and influence society.

As in most of the texts in the anthology, the question seems to come back to citizen assemblies. Where Sachetti et al and Davis’ essays go to the question of public spaces, Revisiting Self-Governance: On Designing a Council of Five Hundred by Gustav Kjær Vad Nielsen offers one of the only historical perspectives on the act of assembling. As Vad Nielsen points out, the ancient Greek Boule, a council created to govern everyday urban matters “was a political project aimed at a form of civic self-governance not unlike the one promised by citizens’ assemblies today.” Akin to this, drawing parallels between the 1920s and 2020s, Mirjam Zadoff’s “The Politics of Spectacle and Display: Some Thoughts on Agonistic Assemblies 1922 / 2022” rightly kicks off the third cluster. In the essay, Zadoff underscores the significant role played by plenaries and assemblies for institutional design. Highlighting the attacks on traditional democratic spaces during the pandemic, she instead calls for “new spaces of assembly—digital and geographical ones” that speak to the new politically engaged youth.

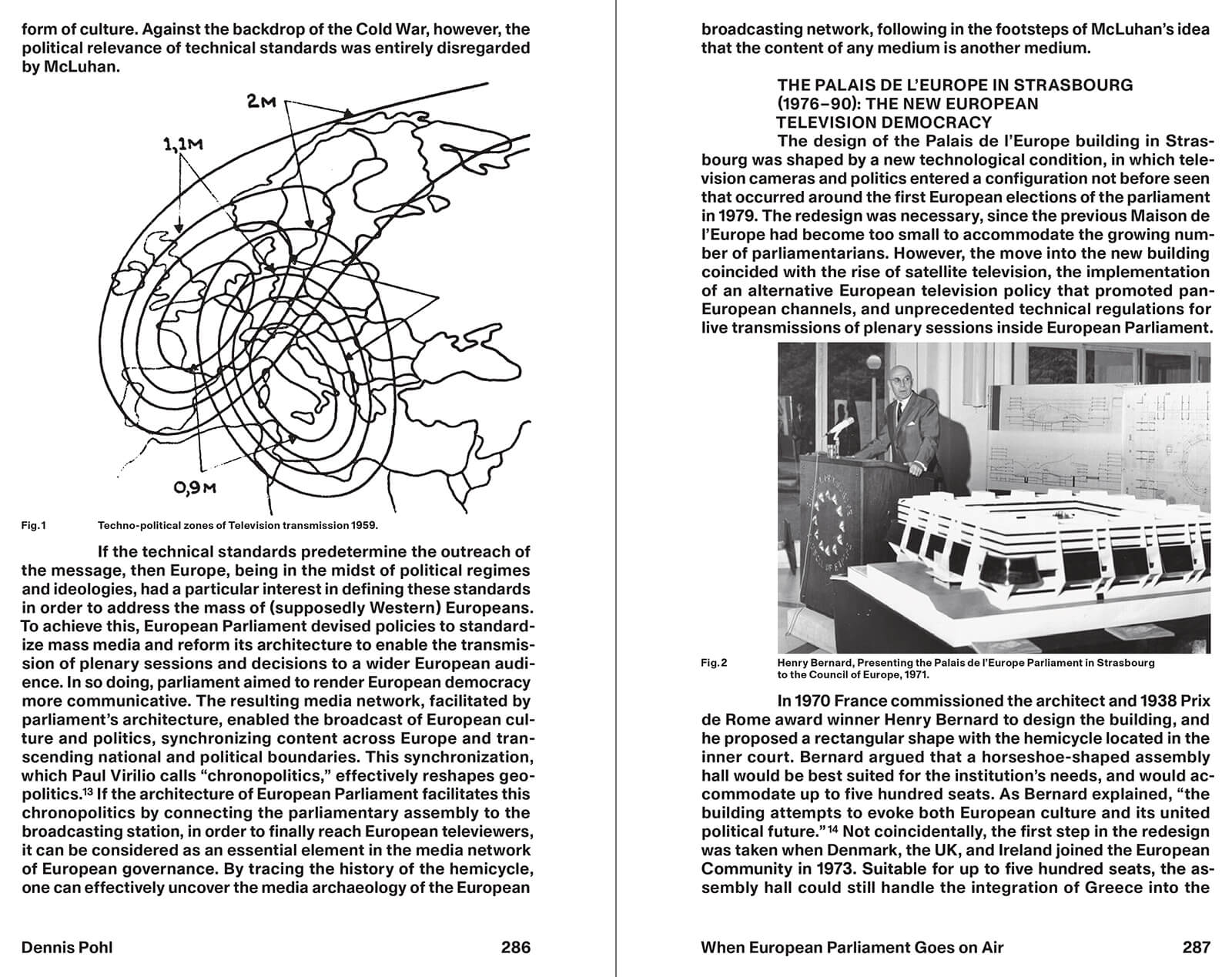

An interesting perspective on this may be presented by Dennis Pohl’s When European Parliament Goes on Air: Television, Architecture, and the European Public which looks at media and how it creates an atmosphere of political immediacy. In the text, he investigates virtual formats of gathering and democratic participation, and the future of digital platforms, thus signalling a new decentralised form of governance. Conversely, as Miessen writes in the introduction, “If every discussion were televised or made public, the real debate would take place elsewhere: in the kitchen or corridor, on the train or in the courtyard, where most authentic conversation already takes place…It is precisely these in-between spaces that need urgent consideration when it comes to the development of spatial frameworks for discourse.” What will our new sites of assembly be?

The very question of sites of assembly concerns another interview in the book, between Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, Markus Miessen and Anne Davidian where the trio discuss how spatial organisation and design can bring people together and enhance/hinder collective decision-making. Barthes astutely answers by referring to Foucault’s theories of power and the “possibilities that designed spaces can hold for benevolent action—that is, if some form of power is handed over to the people.”

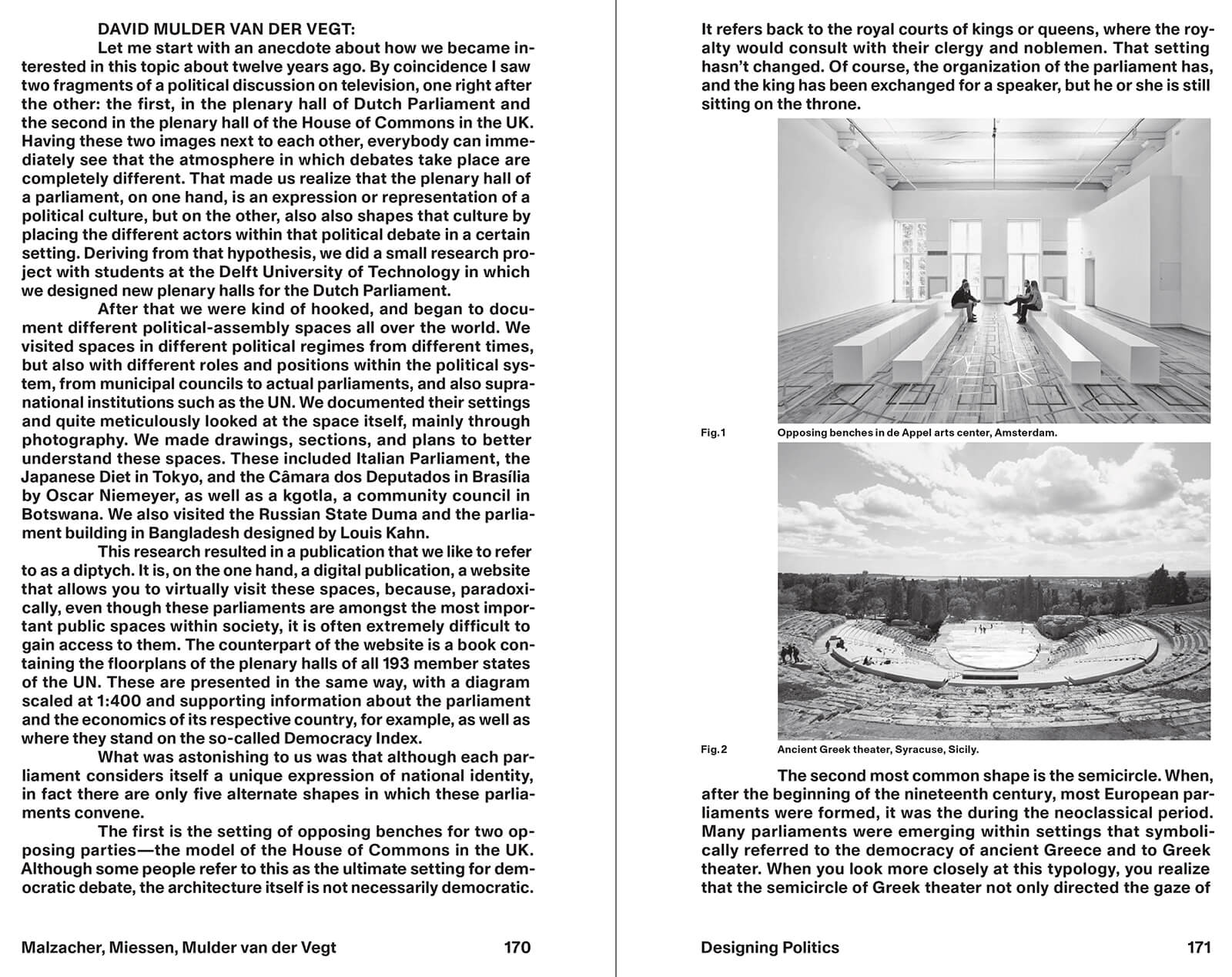

Here, we return to interrogate (a thread that started with Sachetti’s) the classical Western forms of assembly with their parliamentary architectures and how they reflect the distribution of power. Miessen offers an alternative to the Western classical model that consists of three strategic changes, where “a distributed, politically formalised but socially informal assembly” is created which functions on “a decentralised format based on a rotational system between many designated spaces in different cities and communities.” The members would all be picked via a lottery system for short-term roles and all decision-making would be ratified by professional, long-term expert commissions.

Today, we are facing a situation in which it would be naive to talk about “the” public. As a political imaginary, the public is mostly a projected idea, an idealised longing for a somewhat homogenous entity that is factually inexistent. Today, we have to really find a one-to-one scale of urban social life. Publics, a heterogeneous landscape composed of a plethora of multi-scaled actors, stakeholders and constituencies – Markus Miessen, Designing Politics: Architectures of Deliberation and Decision-Making

Perhaps akin to the tree and roof and tents model proposed earlier. Conversely, this question of has the architecture of democracy failed in contemporary society is discursively discussed in Designing Politics: Architectures of Deliberation and Decision-Making by Miessen, Florian Malzacher and David Mulder van der Vegt. In the conversation, the speakers touch upon the “role and (spatial) momentum of parliaments, questions around representation, decisionmaking and agency as well as the potential role of architecture and spatial design in this.” This forms the background to question what could constitute decentralised and distributed forms of assembly.

A helpful text in this regard is Pelin Tan’s contribution On Horizontal Alliances—Scales of Threshold Infrastructures which looks at commoning practices and transversal methodologies at a para-institutional scale. In the text, Tan asserts that “pedagogies have the power to design infrastructures.” Through concrete examples, Tan makes a strong case for how “transversal methodology of learning and action can inform and build alliances.” It is, after all, the book’s hypothesis that alliances lead to new forms of institutionalisation.

Moving from the scale of the individual to the community and urban and then to the more intangible notions of citizenship and participation, the book makes a strong case for community-based action. But what is it all for? Nikolaj Schultz’s postscript Three Points to Remember for the Green Parties gives one clue. His closing of the book, which may at first seem unrelated, is meant to draw attention to the larger moment we exist and act in, one that is defined by a state of crisis: that of climate change and depletion of resources and natural landscapes. In it, Schultz highlights the primary issue with advocates for change in existing political systems (the Green parties in this case). He ends with a bold question to contemporary green politicians: “‘To vote’ is about choosing, about wanting to choose; and who wants to vote for a party that you must vote for, for the sake of the survival of the planet? Who wants to vote for a party that one should vote for, for moral reasons?” Through its exploration of inclusion and participation in political decision-making, the book asks if the people can have more of a stake in our political future. And Schultz’s indictment of how people vote is just one clue as to why we should.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Jul 05, 2024

What do you think?