Books on architecture and design coordinating discourse and knowledge

by Jincy IypeDec 12, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Almas SadiquePublished on : Oct 19, 2023

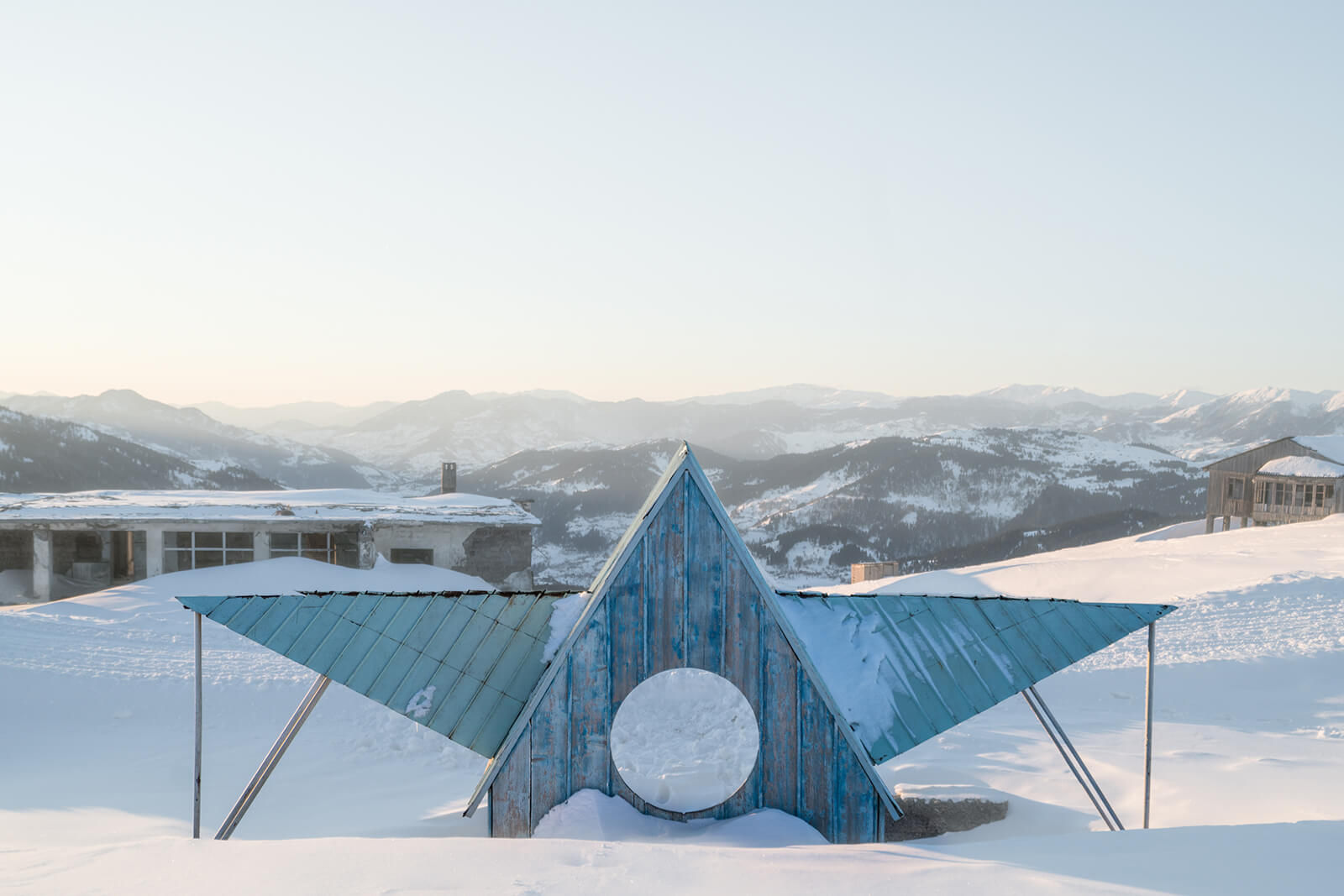

Browsing through the two book volumes that condense Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig’s architectural photography project Soviet Bus Stops, one comes across a litany of uniquely stylised bus stops, designed and built during the Soviet era. Standing in stark contrast against the prevalent notion of regimental construction pervading these countries during the erstwhile period, the bus stops photographed by Herwig are imbued with a complacent and wondrous guise. They speak of their geographical location and the cultures prevailing in the area, serving also as an example of the bizarre and brazen seeping through the stern commandments that dictated contrivances of the past. Much like Herwig's own discipline of photography, these micro-architectures, albeit unintentionally, remit construed perspectives to present an individualistic expression of ideas and thoughts.

Herwig's photographs comprise the documentation of nearly 750 Soviet-era bus stops. These were covered in different phases, hurtling through the parched terrains of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, the undulating cordilleras in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Georgia, the verdant steppes of Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia and Estonia, the marshy territories in Belarus and Lithuania, the partially recognised state of Abkhazia, and across the sizeable expanse of Russia. This monumental project is compiled in two book volumes—Soviet Bus Stops Volume I and Soviet Bus Stops Volume II—as well as in a documentary film titled Soviet Bus Stops - The poetry of the road. Herwig later also published Soviet Metro Stations, which comprises a series of photographs of the stations of each metro network of the former USSR.

English writer, Jonathan Meades, who wrote the foreword for the first volume of the book, mentions, “Christopher Herwig’s obsessional project posthumously illumines the Soviet empire’s taste for the utterly fantastical. It restricts itself to one building type, the bus stop or shelter. The disparity between their banal use and the confidence they display might seem puzzling.” Looking back at his own journey across the Baltics, and the bus stops that he witnessed as being used by the local folk, Meades rhetorically queries, “When did these shelters turn into drop-in centres? Does it matter? It gives them a use. And it gives people who live in remote, pub-less, village-hall-less isolation a place to hang out. The shelters provide an ad hoc social service. Further, they have granted aspirant sculptors, builders and architects opportunities to flex their creative muscles.”

Although most of the designers and builders of these bus stops, referred to as bus pavilions, are unknown, a few were discovered by Herwig with the help of several local researchers (such as Vera Kavalkova-Halvarsson, who grew up in a family of architects from Belarus), artists, designers, architects and enthusiasts. A few of them include Belarusian architect, author and designer, Armen Sardarov; and Georgian artist Zurab Tsereteli. An introductory story by Herwig and a note by Vera Kavalkova-Halvarsson set the mood for the images strewn across the 97-page book.

The second volume commences with an essay penned down by British writer and journalist, Owen Hatherley. He traces his own experiences across countries of the yesteryear Soviet Union, the propaganda communicated by the Soviet state, and the common perception of the transcontinental empire globally. He also discusses the impact of the empire’s violent aggression upon rural areas, as is evident through Herwig’s photographs. Hatherley further proclaims that while these small-scale constructions may seem like forms of dissent against the regimental Soviet state, they are, in fact, a product of the same system, built in order to proclaim the empire’s ideological system on all fronts. By integrating such micro-architectures in the most far-flung places of the empire, each zone became an ‘outpost of the Soviet ideology, a part of the national tradition.’ However, whether it was a provision granted by the government or an opportunity that propped up due to lesser regulations strapping the construction of these bus stops, the simple form of these architectural structures offered their makers a chance to extensively experiment with their form and decorations.

Herwig’s documentary film, Soviet Bus Stops - The poetry of the road, traces the last leg of his journey across Russia, Ukraine, Crimea and Georgia. It details the strenuous process of researching and travelling to remote locations in order to photograph "just one more bus stop," as professed by Herwig. Some collaborators on this 20-year-long project are Nick Zajicek, Kristoffer Hegnsvad, Fisunov, Darya Dmitrienko, Ilya Evlampiev, Yulia Kalinina, Sergey Vyskub, Artyom Kravtsov, Alexander Zima, Evgeny Yakovlev, Valeria Agafonova, Victor Lazarenko, Armen Sardarov, Andrei Palamarchuk, John Zmeikin, Dmitry Zhukov, Nanukå Zaalishvili and Michael Pchelnikov.

Herwig was born and brought up in Canada to his German immigrant parents. He has been working as a photographer for nearly 30 years, ever since he finished high school. Over a video call with Herwig, who is currently based in Sri Lanka, I had the pleasure of learning about the photographer’s practice, the journey that led to Soviet Bus Stops, and the lessons inferred from his experiences travelling across the 15 countries.

Almas: How did Soviet Bus Stops begin?

Christopher: This project came out of a game I was playing with myself while I was riding my bicycle from London to Saint Petersburg. Essentially, what I did was I set out a rule that I had to take a photograph of something every hour. At least one photograph. I had done bike trips before, and on most of these trips, I would wait for a magical moment, that amazing light, that castle on a hill, something extraordinary, something that I thought people wanted to see. I would end up biking for days without coming across something that I felt was worth a photograph. Making this rule of capturing at least one photograph every hour helped me open my eyes to things that were fairly ordinary and that I would never have normally photographed. There were lots of things that I then started to notice in terms of the shape, colour, pattern and graphics. At this time, I also came across several quirky bus stops that were differently designed. I felt that they warranted some attention. During this bike trip, I photographed around 20 of them.

The idea of photographing these bus stops remained stuck in my head even after the bike trip was over. Over the next few years, I lived and worked in different countries of the former Soviet Union, and the project kept on growing. It became a sort of passion for me because I really connected with the humble creativity of these structures, as well as the mystery behind them. I grew up in Canada during the Cold War, and there was a very distinctive opinion we had of the Soviet Union and the communist bloc in which things were very grey and standardised. We believed that creativity was, perhaps, something that did not exist in the area, at that time. Each structure’s purpose was very explicitly apparent. So, to come across these bus stops that subverted this notion was very refreshing.

Almas: What led to the decision to put these down in the form of two books and the film?

Christopher: In all the different stages of this project, for me, nothing was really decided in advance. Initially, there was an exhibition, over 20 years ago, in Stockholm, that documented the bike trip I did across Europe and through the former Soviet states, in the Baltic region of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia and into Russia. I had one wall of the exhibition that was dedicated to bus stops, and I thought I was done with this project. An year after this, I moved to Kazakhstan with my wife and stayed there for 14 years. I started the project again because I started seeing more of these bus stops. It was more for fun and I didn't really see a purpose to it at that point. However, once I got a bit more of a collection together, it got featured on some web blogs around 2005. Some of them got a lot of traction. The project was also beautifully featured in some magazines around the world. I was quite overwhelmed with it. I even compiled this into a little print-on-demand book with all the pictures I had clicked until then. Over the next few years, I kept going back to this project, to photograph more bus stops.

Once I had a collection of photographs, I sent the project around to all the major publishers I could find, and all of them refused to publish it. Perhaps, they did not believe in this project and its potential as a series that could be appreciated by people. I did not want to publish the photographs as part of a vanity self-published book that would end up costing a lot. So, I put up a compilation on Kickstarter, and they sold out in the first couple of days. It was more successful than I could ever imagine. I ended up selling 1,500 copies of the book in just a matter of days. Post this, I began to receive a lot of emails from publishers who were interested in publishing proper copies of the book. It was funny that some of the publishers who had said no to me earlier came back to me, just after the gap of a few weeks. After some deliberation, I signed a deal with FUEL, who published both Soviet Bus Stops Volume I and Soviet Bus Stops Volume II, as well as Soviet Metro Stations. This was the process with the first book.

The second book and the film came hand in hand. In the first book, I had left out Russia, partially because, as a nation, it's often the one country that is seen as being part of the Soviet Union. I wanted these bus stops to be seen as something more than a typical Soviet invention, I wanted to draw focus to the individuals, the local initiatives and the cultures from Kyrgyzstan and Armenia to Estonia and all the other countries. It was only later that I went back to cover the bus stops in Russia, which are now part of the second book.

Almas: Did the bus stops documented by you hint at any inter-city and intra-city linkages that do not exist anymore?

Christopher: Oh, gosh, yeah! I don't even know why some of these bus stops are there in the first place. Looking at the nearby roads, I deduced that some of these bus stops might have served as transfer stations along the bus routes. A lot of the bus stops do not have buses going to them anymore because they are not located in the cities or in busy places. Some of them are located near farms or previously functional workplaces in the countryside. Since they are not operative anymore, these bus stops are not in use. During the Soviet era, a lot of rural transportation was state-funded. However, now that these areas do not host large populations, it is not commercially viable to have buses running in these areas. Some of my favourite bus stops are in the middle of nowhere. There is no house around. There is no town. It's just a bus stop in the middle of nowhere.

Almas: What are some styles that you identified in the design of these structures, and do they bear the influence of the architecture in the region? What are some examples of Soviet socialist art and local themes that you came across?

Christopher: Some of the bus stops had very strong local influences. Most of the time, it would be in the way they were decorated. In Ukraine, you could see mosaics depicting men and women in traditional clothing or depicting local folklore. In some places, one can see a more literal representation. For example, in Kyrgyzstan, some bus stops bear the images of a local hat, like a 'kalpak.' Some other bus stops in Kazakhstan bore patterns and icons with an Islamic theme, bearing semblance to mausoleums and mosques. Another one in Turkmenistan had an image of what can be interpreted as the Silk Road. Most of these bus stops were made using local materials, in order to comply with the limited budget available. In Estonia, one can find bus stops made of wood, and in Armenia, a lot of them were made of concrete and bore a more Brutalist form. In Ukraine, which is famous for its mosaic tiles, one can witness the usage of these tiles in bus stops.

Almas: What is the main reason behind the demolition of the bus stops?

Christopher: There are several different reasons why the bus stops are getting demolished. Because these are old structures, it is often a lot more difficult to repair them. So, if they involve mosaics or other specific parts, it’s not like you will easily find reserved standardised parts for them. Each damaged portion requires some specific care and maintenance. A lot of people don't find them attractive because they have fallen into disrepair. They are not seen as anything beautiful or modern. They are looked upon as being outdated and ugly by some people, or as a reminder of the Soviet past. For a lot of people, that was a time of oppression, occupation and lack of freedom. A lot of people also see it as an extension of the Russian Empire or Russian influence, as well. Given Russia's current aggression in Ukraine, I think it is understandable when people prefer to dissociate themselves from these structures. At the end of the day, it still is just a bus stop. There are more important things out there in the world, and if they were to be removed tomorrow, it would be understandable.

Almas: Which region from amongst the countries documented by you did you enjoy the most?

Christopher: I really enjoyed the regions with undulating topographies a lot, for example, up in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan as well as in Armenia and Georgia. However, every place is different and has its own charm.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Almas Sadique | Published on : Oct 19, 2023

What do you think?