Books on architecture and design coordinating discourse and knowledge

by Jincy IypeDec 12, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Manu SharmaPublished on : Jan 15, 2025

The Color Black: Antinomies of a Color in Architecture and Art, published by MACK, United Kingdom, on August 1, 2024, traces the longstanding relationship of art and architecture with the colour black. The 150-page hardcover book presents an essay of the same name by Iranian-American architect Mohsen Mostafavi, along with the first-ever English translation of its accompanying essay, The Color Black: On the Material Constitution of Form, written by Marxist German-American art historian Max Raphael (1889 – 1952) after he left France for New York, following a harrowing stint in a Nazi internment camp.

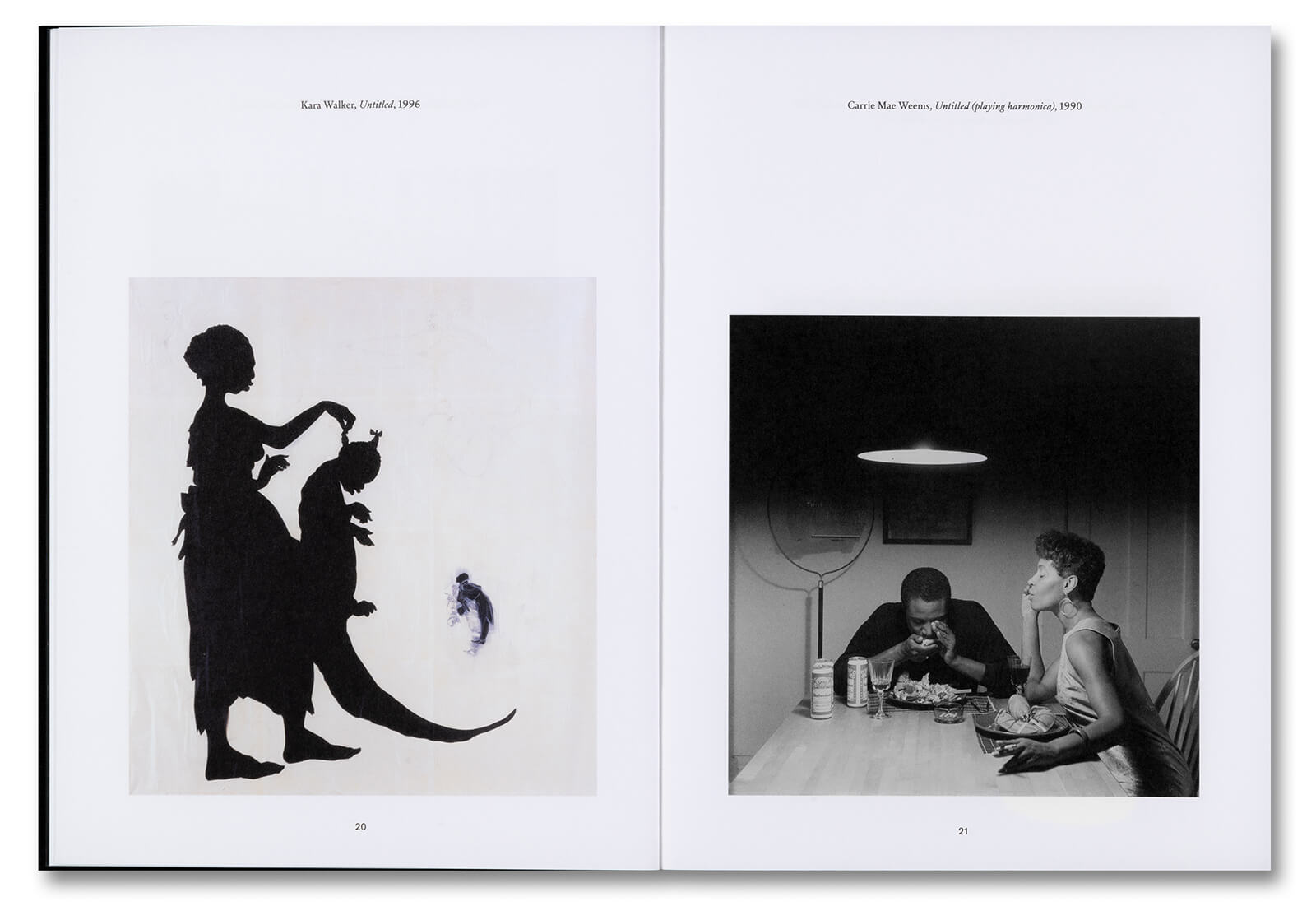

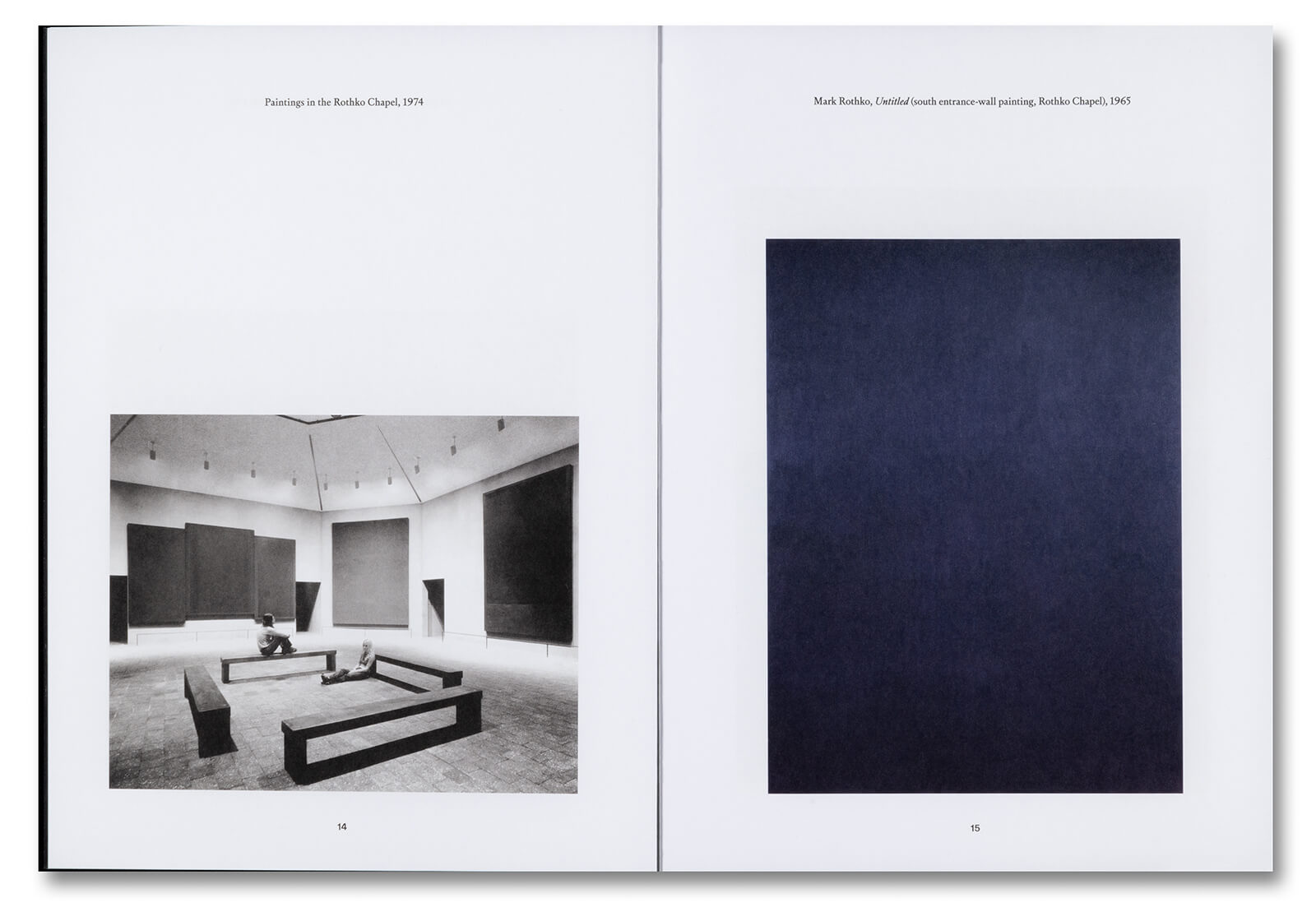

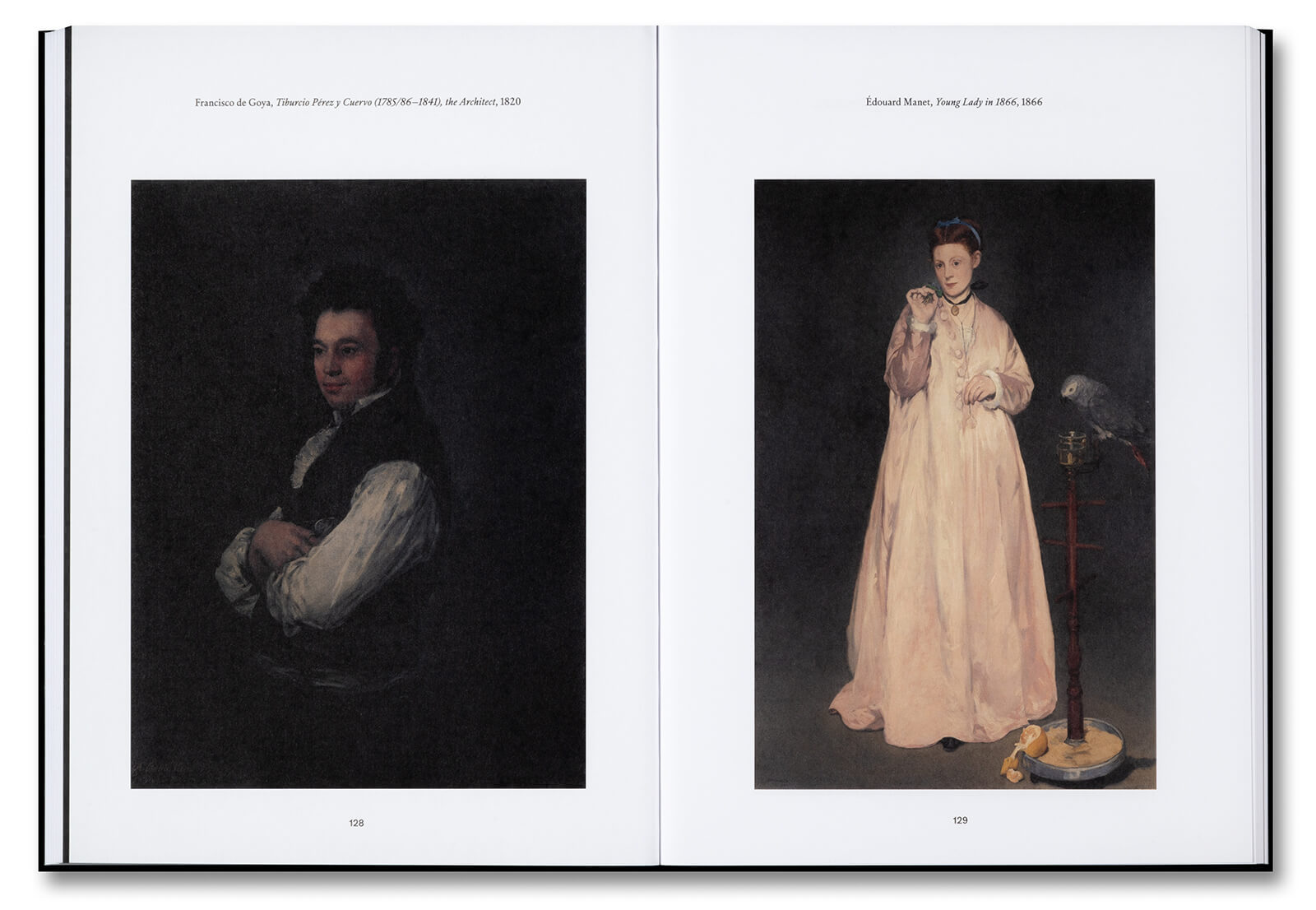

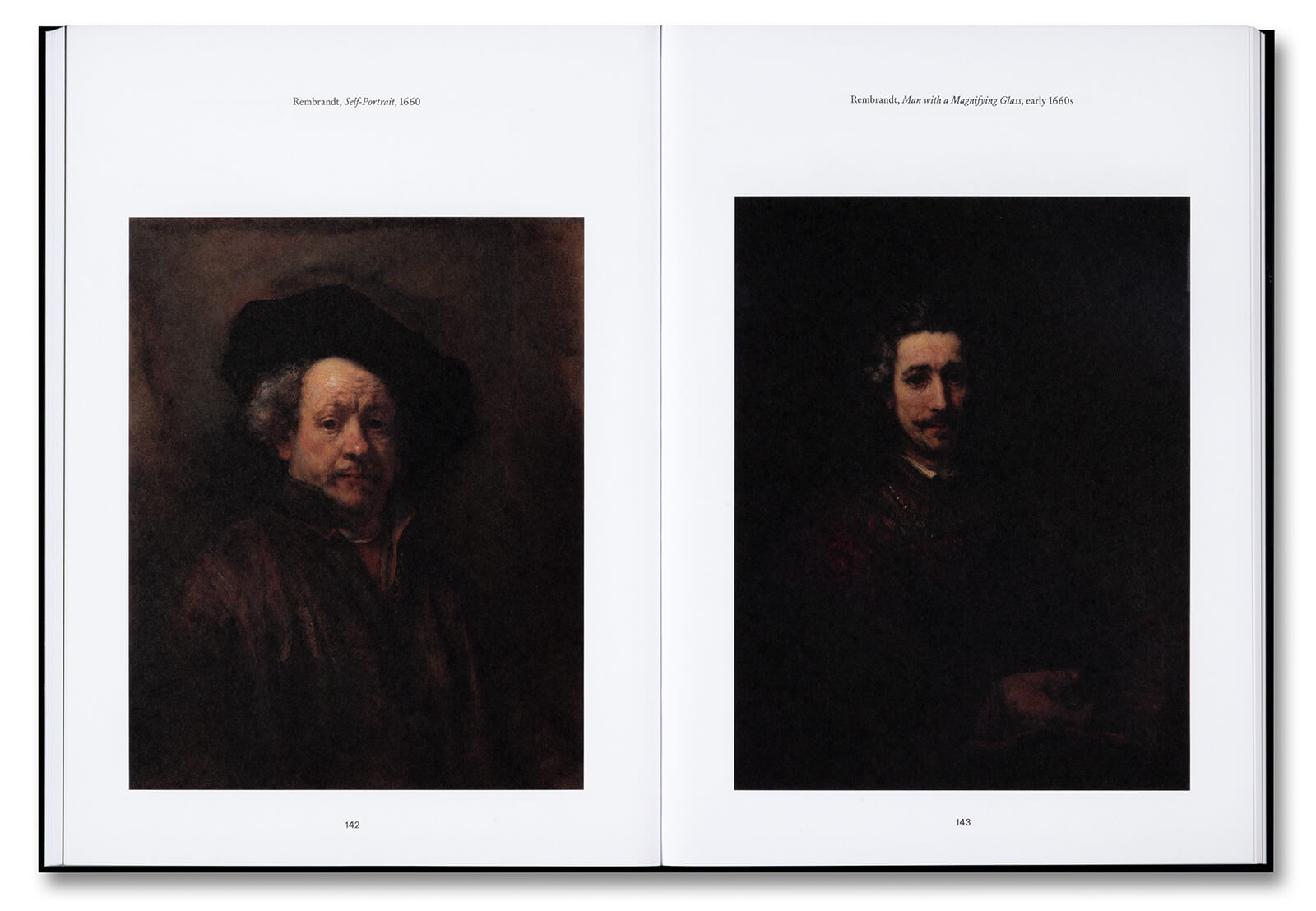

In the essay The Color Black, Mostafavi explores art and architecture’s relationship with the colour and highlights the cross-pollination of ideas surrounding blackness. The architect looks at architectural and artistic works from around the world, touching upon Japanese screens, the paintings of Mark Rothko, the buildings of Adolf Loos and more. Mostafavi assesses the role of blackness in these works from various lenses, discussing its political, emotional and aesthetic implications. Meanwhile, Raphael contextualises the value of black within his larger ambition to develop an empirical theory of art, built upon observations and theory, as Raphael hoped for his theory to apply to all people, everywhere. The art historian engaged in a close study of artworks at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, informed by Marxist theories surrounding art. Raphael was particularly preoccupied with Marx’s view that art could not be dislodged from the circumstances of its production and that a reading of artwork should include an assessment of what it tells us about the social and political conditions under which it was produced. The essay, On the Material Constitution of Form, was originally published long after it was written in 1984 in German (as Die Farbe Schwarz: Zur materiellen Konstituierung der Form). Translated by Pamela Johnston, the essay is not widely known, and Raphael would not live to see it receive significant readership as he tragically took his own life in 1952.

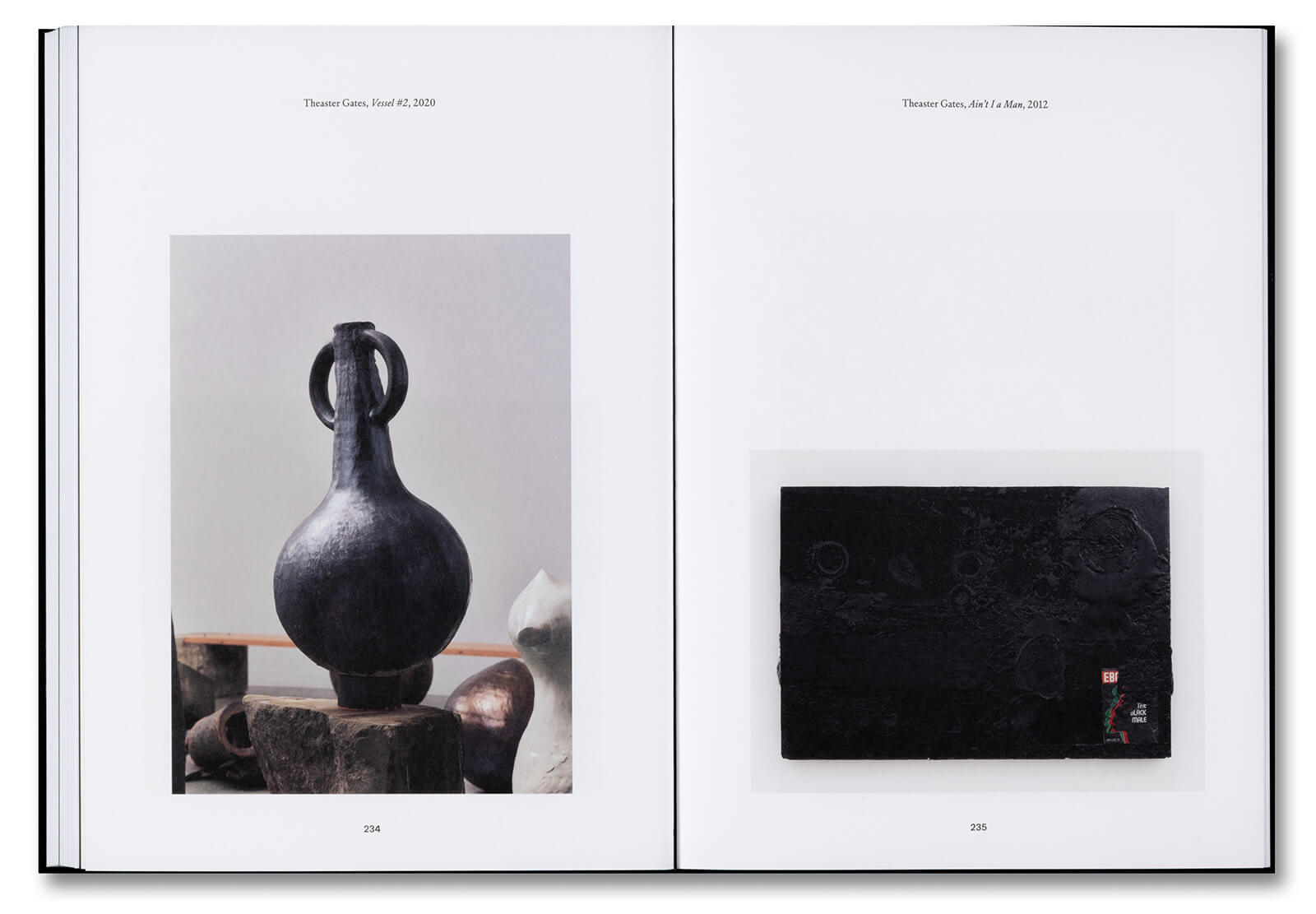

The book The Color Black also contains conversations with Swiss architect Peter Märkli and American artist Theaster Gates. Märkli is inspired by Raphael’s work, having originally taken an interest in the art historian’s writings due to his observations on the purposely irregular stones and joints found in Romanesque churches in France. Raphael believes this is a sign of humility, with the architects eschewing the pursuit of perfection to express their subordination to God. Meanwhile, Gates is interested in the political implications of colour and how it can be used to express cultural blackness relating to African and African American communities. For example, Gates’ Black Chapel (2022), designed as the 21st Serpentine Pavilion in London, took inspiration from traditional African structures found in Cameroon and Uganda that are used for sacred ceremonies.

It was possible to imagine an architecture of black, albeit one confined to the two-dimensional page. – Mohsen Mostafavi, architect

Mostafavi begins his essay by stating that architecture and architectural history do not engage with blackness to the same extent as whiteness. In his words, “There is scant documentation on the subject in the form of either writings or, until recently, buildings. Instead, it is the aesthetics of the colour white—the use of white paint to highlight the volumetric composition, especially during the heyday of modernism—that has dominated discussions in architecture.” Mostafavi turns to art, writing, “By contrast, the colour black possesses a long and complex history in art.” He also gives us a famous example of an artwork that engages with blackness conceptually as well as formally: Black Square (1915) by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich (1879 – 1935). Malevich wished to create a “zero point of painting”, from which he could begin anew and build a new visual language – Suprematism. Later, Mostafavi turns our attention to the American artist Mark Rothko’s (1903 – 1970) black paintings, made from the mid-1960s onwards, to present an example of the emotional application of the colour black. These works are associated with Rothko’s battle with physical and mental illness at the time, and Untitled (Black on Grey), completed in 1970, would be the painter’s final work before taking his own life. We can read these works as an expression of the absence of “light”—joy or hope—in Rothko’s final days.

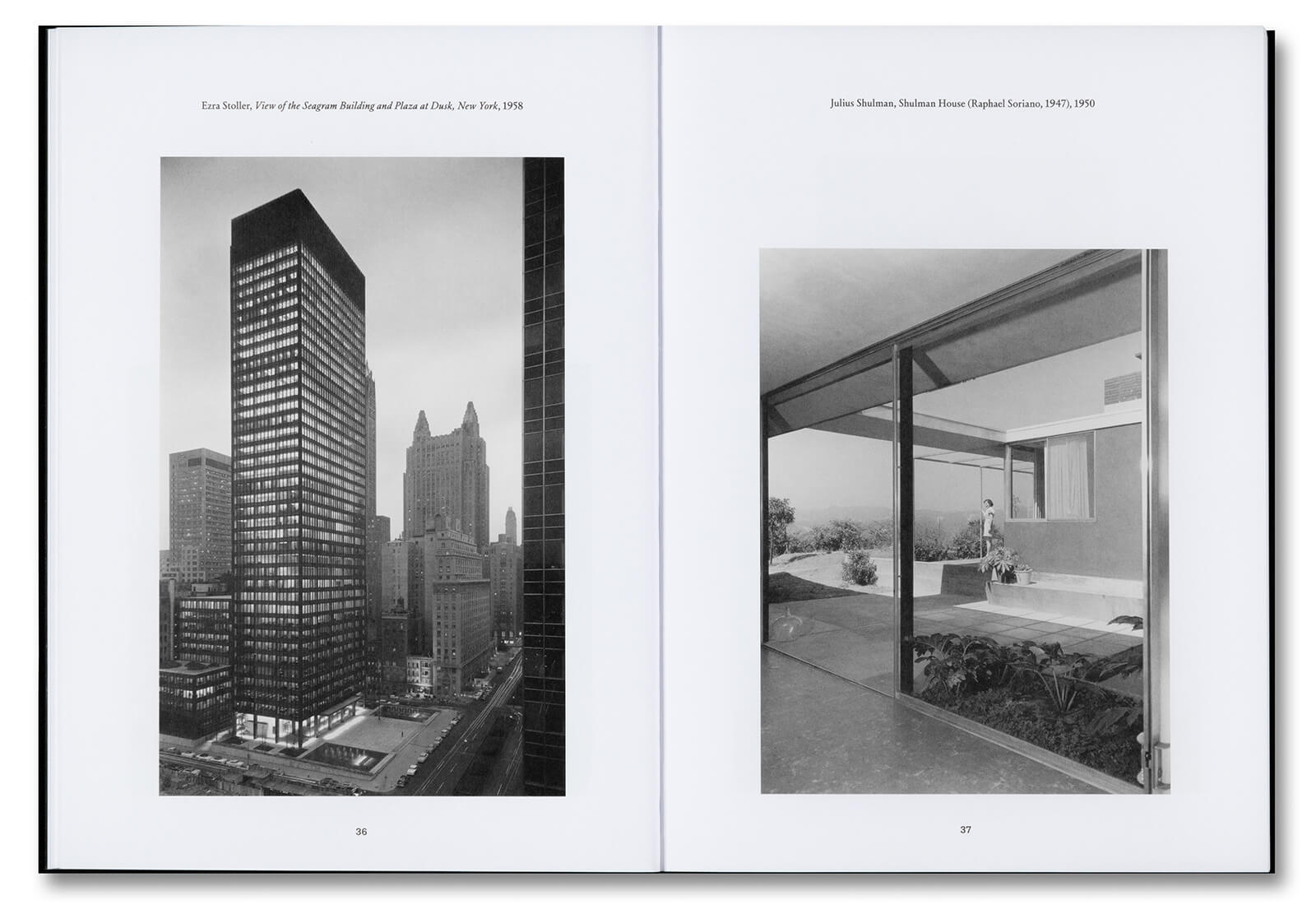

Mostafavi returns to architecture later in his essay. Taking the example of London as late as the 1960s, he explains that during the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries, metropolitan cities were characterised by buildings stained by smog and soot. While this was not by design, it lent a blackness to the architectural impression of these cities. Mostafavi writes that this accidental articulation of blackness created a negative connotation for many, giving us the example of American photography pioneer Henry Fox Talbot (1800 – 1877), who wrote of Westminster Abbey that the “swarthy hue” serves “wholly to obliterate the natural appearance of the stone” and the “sooty covering destroys all harmony of colour and leaves the grandeur of form and proportions”.

The author quotes American architect Hugh Ferriss’s (1889 – 1962) book The Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929), which gives us further insight into how the metropolitan cities of the time were regarded by commenters. Ferris describes these cities in preternatural terms, writing, “Going down into the streets of a modern city must seem—to the newcomer, at least—a little like a descent into Hades. Certainly, so unacclimated a visitor would find, in the dense atmosphere, in the kaleidoscopic sights, the confused noise and the complex physical contact, something very reminiscent of the lower realms.” One imagines that the predominance of black-stained facades added to the imposing and alienating quality that cities like New York and London seem to have held.

Mostafavi turns his attention to modern artists and photographers to highlight their perspectives on blackness in architecture by looking at some striking illustration work and photographs produced through the predominant usage of black and darker shades of grey. He brings to our attention works such as the oil painting Radiator Building—Night, New York (1927) by the American painter Georgia O’Keefe (1887 – 1986), American photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s New York from the Shelton (1935) and Ferriss’s drawing study for the maximum mass permitted by the 1916 New York Zoning Law, which he created in 1922. The author also explores the impact of chiaroscuro on architectural photography and cinematography. Chiaroscuro, Italian for ‘light-dark’, is a term in visual art for the interplay between white and black, used to emphasise volume. Mostafavi considers American cinematographer Gregg Toland (1904 – 1948), who was responsible for the striking shots of buildings in Citizen Kane (1941), saying, “[For Gregg Toland] shadow became a means of separating the foreground from the background and of producing a powerful sense of depth of field.” Mostafavi goes on to remark, “It was possible to imagine an architecture of black, albeit one confined to the two-dimensional page.” One will include some of the other films of the times he is discussing here as well. Beyond Citizen Kane, Metropolis (1921) comes to mind for its stunning depiction of futuristic architecture, which is still discussed today. Another example is The Fountainhead (1949), which revolves around the debate between individualism and collectivism through architecture and is filled with a variety of shots that capture the grandeur of New York’s buildings.

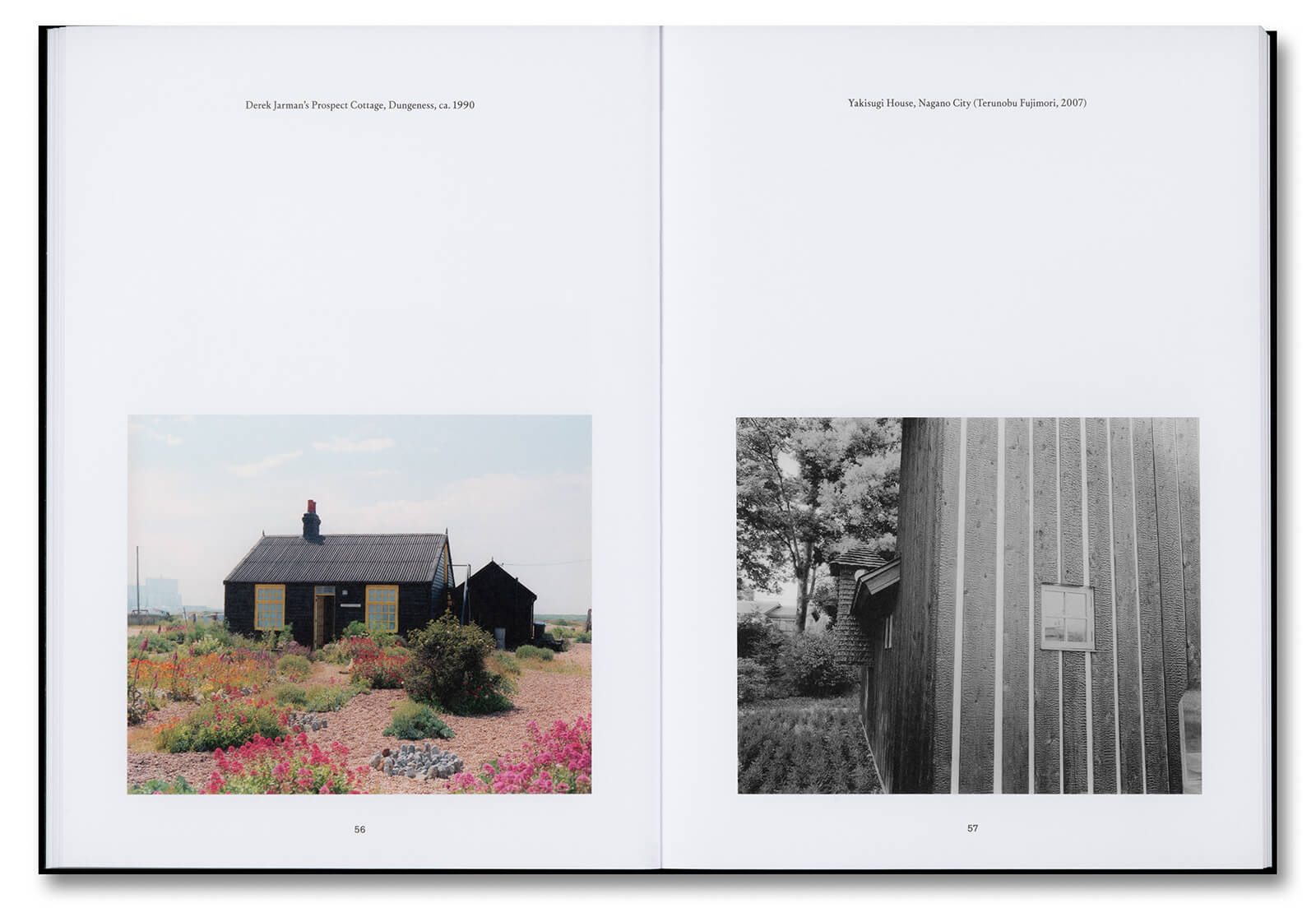

Looking at contemporary architecture, Mostafavi notes architects are finding greater interest in the colour black today, giving the example of Peter Märkli’s Picassohaus office complex (2002 – 2008) in Basel, Switzerland. The building is understated yet stands out for its facade, which is composed of black interwoven flat and horizontal steel segments. Viceversa’s Jeff Kaplon discusses Picassohaus, writing, “The result, quite simply, is a beautiful building. A completely alluring structure with refined proportions and a combination of materials, finishes, and details that are as technically proficient as they are aesthetically pleasing. Picassohaus sits on the plaza with immense confidence while being entirely accessible.”

Mostafavi concludes his essay by exploring Raphael’s perspective on blackness in art before the book presents the art historian’s essay The Color Black: On the Material Constitution of Form. He tells us, “While recognising the relations between art and its social context, Raphael saw the value of art residing in the activity of the artist—in the process by which they transformed raw material into artistic material representing an idea.”

The author narrates Raphael’s study of the works he encountered in New York, explaining that the art historian observed that black served predominantly as a supporting colour in historical paintings. As Raphael puts it, “The colour black forms a neutral ground because it is the ground of the absolute; it contains everything but manifests nothing.” The art historian believed that black allows other colours to pop out and contextualises the spatial qualities of the subject of a work, which can carry strong political implications. For example, looking at Diego Velázquez’s (1599 – 1660) Philip IV (1605 –1665), King of Spain, Raphael notes that the black clothing worn by the king appears to bestow a sense of weightlessness to him, enabling him to transcend his role as a sovereign and become seemingly divine.

Through his essay, Mostafavi develops an intergenerational and cross-disciplinary dialogue with Raphael’s theoretical work. Towards the end, he lauds the art historian’s study, writing, “What is superbly inspiring is the way in which his analysis constructs a material archaeology of each painting. For an architect, Raphael’s descriptions are like a set of specifications or construction documents that simultaneously describe the quantitative and the qualitative aspects of the architecture and its materials.” Altogether, The Color Black is an ambitious undertaking that looks at a large number of drawings, photographs and paintings, offering readers an episodic yet dense study of blackness’ implications in Western art and architecture.

‘The Color Black: Antinomies of a Color in Architecture and Art’ was published by MACK in the United Kingdom on August 1, 2024.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 13, 2026

As media culture is transformed by the social internet and AI tools, the filmmakers of ‘Low Signal Feedback Loops’ adopt a new visual language to critique and interrogate it.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 11, 2026

The 82nd Whitney Biennial 2026 is a group show that reflects the ‘turbulent existential weather’ of the United States today.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 06, 2026

The British artist’s solo exhibition, ZOT at Varvara Roza Galleries in London, takes a postwar, postmodernist peek behind the curtain of artist studios.

by De Beers Feb 27, 2026

The immersive installation by De Beers, featuring artist Lakshmi Madhavan, framed natural diamonds through art, nature and human expression at India Art Fair 2026.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Manu Sharma | Published on : Jan 15, 2025

What do you think?