In Minor Keys: Venice Biennale 2026 reveals its curatorial theme

by Mrinmayee BhootMay 27, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Charlotte JansenPublished on : Apr 23, 2024

The words come at you again and again as you wander the streets of Venice: Foreigners Everywhere— Stranieri Ovunque. A xenophobic slogan? A paranoid whisper? A statement of fact? An expression of solidarity? The ambiguous, disquieting title of Adriano Pedrosa’s International Exhibition at the 60th Venice Art Biennale deliberately riffs on the possible politicised interpretations of the phrase, and this becomes the curatorial premise for his exhibition. “First of all, that wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners—they/we are everywhere. Secondly, that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner,” Pedrosa stated in a press release. In the context of Venice—a city overwhelmed with 30 million tourists a year—and during one of the busiest weeks of the year, as the art world descends from all over, the phrase is also tinged with irony. Yet from this promise of possibilities, the exhibition becomes a tangled, cumbersome web of practices of 332 artists, that falls short of reflecting anything clearly about what it means to exist or make art as an outsider. The exhibition perhaps becomes a victim of its own ambition—the sheer breadth of works and approaches rendering real depth impossible.

Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. – Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism (1993)

Pedrosa’s exhibition title also derives from a work by the artist Claire Fontaine, which is included in the exhibition. The work, which began in 2004, has been created in various iterations and numerous languages since it comprises a series of neon signs depicting the words “until now”, but never in English. At the Biennale, they are suspended over the water, under the arches of the Arsenale, looking out to the Grand Canal, a glittering rainbow that creates neat optic effects with the reflections of the water. Fontaine’s work, in turn, is a homage to the Turin-based collective, Stranieri Ovunque, who campaigned against racism and xenophobia in the 2000s in Italy—but seem to have dissipated. It seems an oversight that their work, too, is not revisited here.

Foreignness, migration, exile and estrangement are glaring themes, paradoxically, in a globalised world. Pedrosa explores the idea of foreignness in the art world by including a majority of 'self-taught’ artists (a term many who have attended art school may still identify with) and who have never exhibited at the Venice Art Biennale. Many of them also come from the Latin American region, where Pedrosa works as the artistic director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP). This means some vibrant new and old works appear in an institutional setting in the West for the first time: at the Arsenale, Claudia Alarcón and Silät—a collective of artists from the Wichí communities of Santa Victoria Este, Salta, Argentina—have created a suite of new large-scale textile pieces made from the fibres of the chaguar plant, native to the area, and employ the ‘yica’ stitch technique, a cultural heritage in itself. Their glorious, vivid geometries and colours recount stories and dreams of elders in the community and contain coded warnings about the menace of nature. These stunning pieces materially contain notions of nativism – turning us, the viewers, into foreigners.

The cohort of textile artists at Foreigners Everywhere is particularly strong. In conversation with Alarcón and Silät are works by Arpilleristas, a group of unidentified Chilean artists, which are made up of embroidered, appliqued and crocheted cloth depicting scenes of everyday village life with astonishing details. The patchworks became popular in Chile during General Augusto Pinochet’s regime—they were made collectively by women and often thread together their concerns for their position in society, a form of protest that relates to the quilt makers of the Deep South in the United States. Also emerging from the same period in Chile is a giant work by Las Bordadoras de Isla Negra, commissioned to be recognised as a work of the people—the characters who feature are real figures, including the Chilean poet-diplomat and politician Pablo Neruda, who catches butterflies. The textile was stolen in September 1973, after Pinochet took over the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) headquarters in Santiago, which it was made for—it only reappeared in 2019.

Foreigners Everywhere invites comparisons with Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Art Biennale edition titled The Milk of Dreams and Okwui Enwezor’s 2015 All the World’s Futures that attempted to address the silence and elisions of groups of people and interrogate the hierarchies of value and beauty endemic in the art world. Yet unlike those exhibitions, Foreigners Everywhere feels clumsy and confusing, and the conflation of “outsider”, “foreigner”, “migrant” and “other” becomes knotty and hard to follow; there’s a room of paintings by Italian ex-pats, cased in glass easels by emigre architect, Lina Bo Bardi, that doesn’t seem to make any point beyond the obvious idea that people move and their art becomes influenced by their surroundings. Art has always been made in every place and circumstance, and has always been dependent on fusing different cultures and traditions; this point feels somewhat laboured.

Pedrosa has favoured a conventional installation and traditional mediums; the show is dominated by textiles, sculptures and paintings, and has given more space to each artist, rather than representing artists with single works that connect more (as Alemani mostly did) and the pace therefore, sometimes becomes repetitious and disjointed; there are so many paintings by the American artist Louis Fratino at the Giardini, for example—it feels more like a solo presentation. Two beautiful walls dedicated to the Bolivian photographic artist River Claure, painted in pale pastels, with works from his restaging of the novel The Little Prince in Andean communities, part magical realism, part social docu-fiction, are cut and pasted from the artist’s solo show in La Paz in 2022. How they join up to what is around them is unclear, however.

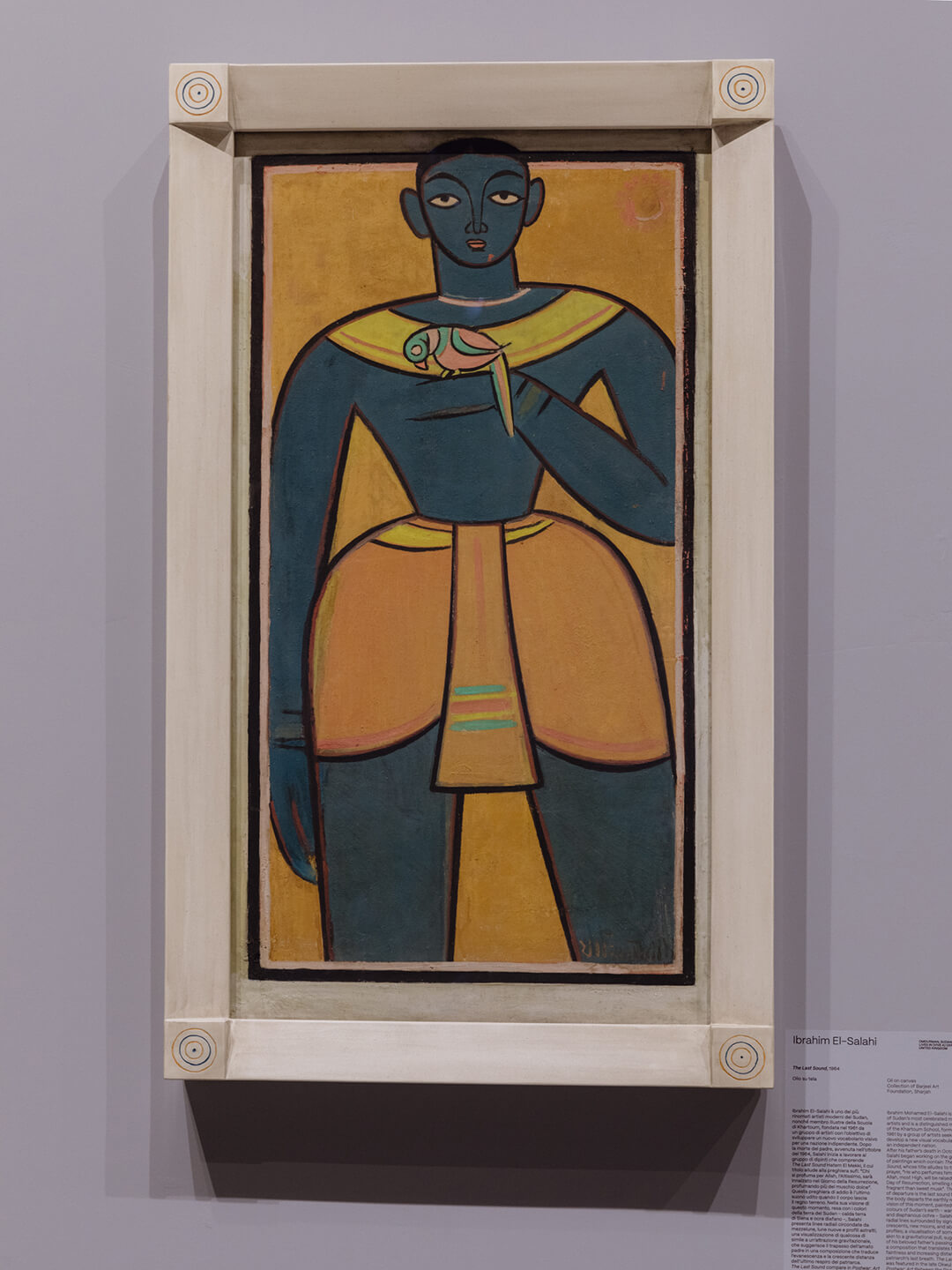

Elsewhere, the Indian artists Karnika Bai, Shanthi Muniswamy and Jyothi H, who form part of the Bangalore-based art collective Aravani Art Project have painted a monumental new site-specific mural at the Arsenale, titled Diaspore (2024). The mural bookends the exhibition, a self-portrait and a celebration—marking a decade since India’s landmark recognition of transgender individuals—a caged bird set free symbolising the release from a body that has become a prison. It is only much later, in the central pavilion part of the exhibition at Giardini, that I come across a small painting by the late modernist Jamini Roy of Krishna holding a parrot, that Diaspore reveals a whole new historical trajectory.

Pedrosa’s attempt is brave, and bold and has moments of brilliance, but as a whole, it is incoherent and incomplete—perhaps purposefully so.

The exhibition on the whole feels more like a museum, but taken as an exhibition it lacks the rhythm and flow that allows you to feel, sense and see connections or visual through-lines between works—without relying on wall texts to understand them. This makes its meaning less accessible and more academic. Sensational pairings do emerge—such as a room at the Giardini, which brings together Dean Sameshima’s black and white pictures, being alone (2022), photographs of men watching films at adult theatres in Berlin, with shadowy vintage gelatin photographs from El Negro (1979) by the Colombian conceptual artist Miguel Angel Rojas, taken through the hole in the bathroom door of the Teatro Mogador, a cinema in Bogotá’s city centre where clandestine intimate encounters took place. Together they dovetail lust, loneliness and repressed sexuality; universal, perennial desires shrouded and repressed by capitalism.

Curating the main exhibition at the Venice Art Biennale 2024 seems like a poisoned chalice; a career-defining moment for a curator but one that’s almost impossible to get right. Pedrosa’s attempt is brave, and bold and has moments of brilliance, but as a whole, it is incoherent and incomplete—perhaps purposefully so.

At the heart of this exhibition is the idea captured by Edward W. Said in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993), “Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.”

Foreigners Everywhere is successful, ultimately, in its interrogation of the very existence of the main exhibition and who it is for. It begs the question of why the main exhibition needs to take over so much space—rather than create more pavilions for countries that are still absent and not represented, especially when most of the excluded nations are from the Global South. But it is also hard to make these points when following the Western rules of exhibition-making so closely, in a European cultural centre for the cultural elite.

Yet Foreigners Everywhere ultimately seems out of step with the contemporary spirit, and not only because it leans heavily on historical works and traditional mediums (there is very little photography, some moving images and film, and one digital art, which seems a glaring omission given the ability of all of these mediums to transcend physical boundaries and borders). Surely, in contemporary society, the majority of lived experiences are not of foreignness but of familiarity everywhere, which is the result of another colonial machine: the internet. At stake in a global, visually mobile, hyperconnected world may lead to the homogenisation of culture, the sameness and ubiquity of everything.

The mandate of the 60th Venice Biennale, which aims to highlight under-represented artists and art histories, aligns with the STIR philosophy of challenging the status quo and presenting powerful perspectives. Explore our series on the Biennale, STIRring 'Everywhere' in Venice, which brings you a curated selection of the burgeoning creative activity in the historic city of Venice, in a range of textual and audiovisual formats.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Charlotte Jansen | Published on : Apr 23, 2024

What do you think?