How to decolonise a monumental ode to colonialism?

by Rosalyn D`MelloNov 20, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Rosalyn D`MelloPublished on : Dec 10, 2021

Andrei Siclodi, director of the Innsbruck-based Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen and founding director of the Fellowship Program for Art and Theory, relishes taking each year’s selected fellows to shadily legitimate Austrian museums. I seem to almost enjoy being able to share his discomfort with other artists, theorists, and curators. One of the most exciting aspects of my ongoing term as a fellow has been this guided introduction to spaces in and around Innsbruck I would either not have encountered on my own, or to complex museological sites that memorialise without complicating difficult histories. Siclodi is of Romanian origin and I think it’s his unique outsider eye I relate to most. It distances him from feeling any urge to be ambassadorial, instead offering fellows the privilege of seeing things more dispassionately. Like me, he is also either angered or amused by certain grandiose forms of display and token gestures made in earnest in order to offer the appearance of inclusiveness.

One of the museums in Andrei’s orientation itinerary in October included the well-funded but not so frequently visited Tyrol Panorama Museum, dedicated to a 360-degree painting covering a 1000 square-meter canvas, made in 1896, portraying the third battle of Bergisel (August 13, 1809) set against impressive Alpine landscapes. As you make your way to the lower level to encounter the painting, you pass by a series of plinths over which are poised statues of key figures involved in the lead-up to this battle, beginning with Napoleon and of course including the Tyrolean folk hero, Andreas Hofer. A few plinths are left intentionally blank, and signs attest to the deliberate anonymity, an attempt to acknowledge the unrecorded contributions of women. It’s a gesture that gets lost in the sea of towering male figures and within the museum’s propagandist furthering of the myth of Tyrol. It’s the lack of criticality, the somewhat jingoistic tone that feels unnerving. In a separate section, for instance, the trauma of the separation of Tyrol is evoked through a digital display of posters that villainise Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany for the historic role they played in the partition of the regions that lie on either side of the Alps, the creation of the regional entity of South Tyrol. What is sorely missing, however, is any form of reflection on Austria’s complicity in furthering the events of World War II and its role in the Holocaust. By investing in perpetuating the myth of Tyrol and in projecting the Austrian state of Tyrol as a victim of fascism, the complexities of its complicity are conveniently erased.

Some weeks later, Siclodi enticed us into a trip to the nearby city of Schwaz, historically a silver mining centre, in fact, the largest mining metropolis in Europe in the 15th and 16th century. His intention was to bring us to the Museum der Völker (House of Peoples), which was built in 1995 and housed the collection of the photographer and journalist, Gert Chesi. In 2016, Chesi donated his collection of objects and artefacts amassed from Africa and Asia to the city of Schwaz. We were told that recently, thanks to changed curatorial directorship, the museum’s display and focus had been reoriented to allow for greater self-reflection, but the issue of provenance of most of the objects remains opaque. Is it enough for a photographer whose career seems to have profited from an uninhibitedly orientalising gaze to simply say he ‘collected’ objects from Africa and Asia without adequately supplying information on the details? If they were acquired, then from whom? If through dealers, then can we be sure they weren’t stolen?

Though the freshly curated display tries to offer overarching thematic structures within which to view the numerous statues of Buddha, for example, which are housed as part of the opening section, there is too little information to contextualise the nuances of the iconography. For instance, what makes a statue of the Buddha from Myanmar unique from one from Java? When I asked one of the curators if the narrative panels that had depictions from the life of Buddha had the Jataka tales as their source, she admitted to knowing nothing about this canonical piece of Buddhist literature. The next room was dedicated to objects that purportedly revealed various world views, contextualising elements of Christianity, for instance, alongside indigenous sculptures from Papa New Guinea, or a statue of the Nataraja. The curators used display techniques to encourage viewers to reflect on what constitutes their personal ideological frameworks. But I wondered if this just nullified the intensity of the objects on display and their history?

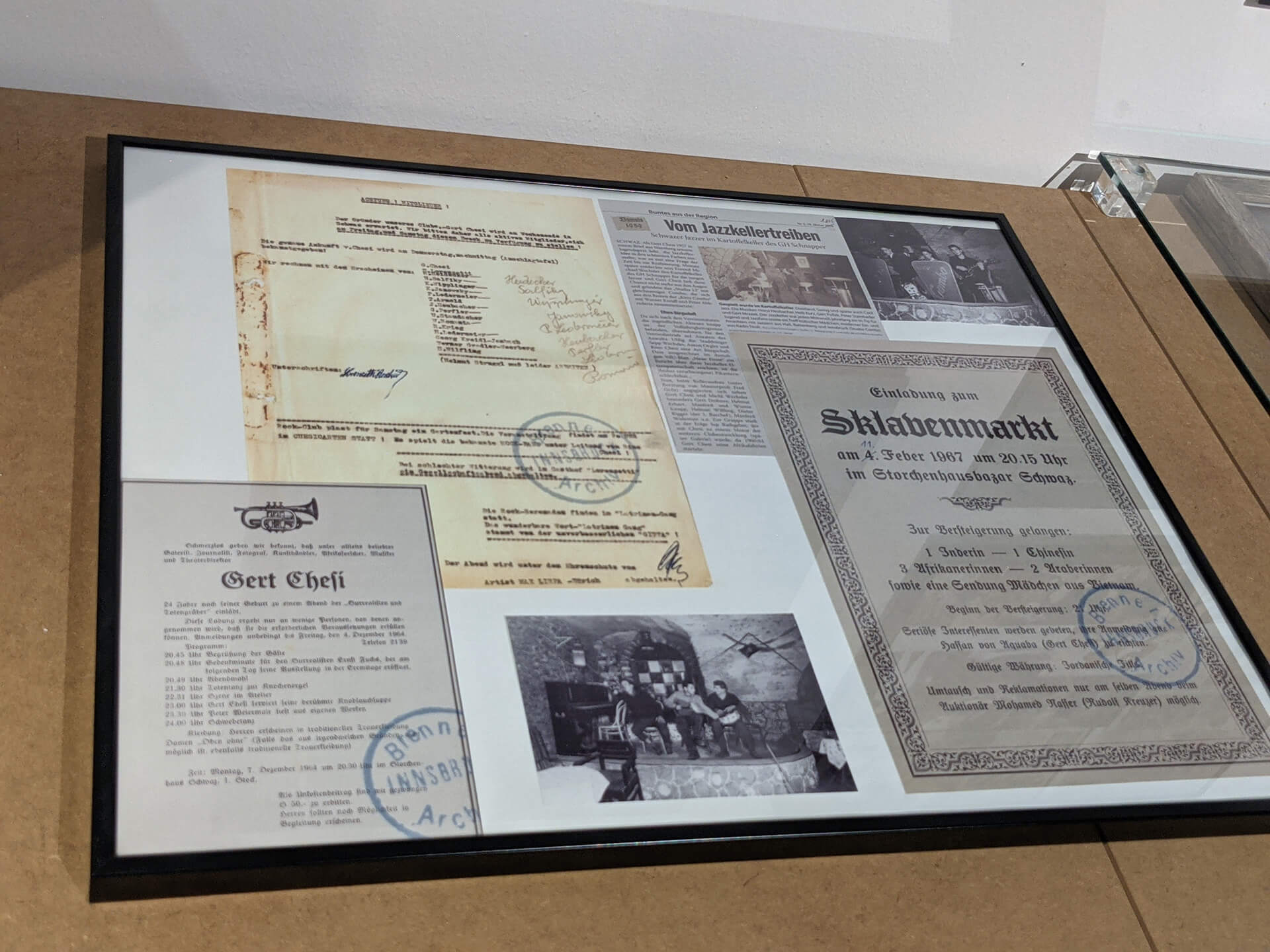

Most provocative, and perhaps daring, curatorially speaking, was the upper-most room in which were housed innumerable artefacts of various sizes, all of African origin, many without any information on their original design. Were they meant to be ritualistic, were they used in ceremonies, or to mark the sites of the dead? The curator who guided us told us the present team was researching ways and means of repatriating these objects and was coldly critical of Chesi’s methodology as a collector. Some objects testified to a pre-Islamic past in certain parts of North Africa, but with limited resources, the information they had managed to compile was not significant. As we neared the end of the tour, we came upon a vitrine displaying the various passports held by Chesi, who is now in his 80s, suggesting how vastly well-travelled he was, and his passion for jazz. But beside them was a collage that upset me, a poster for a ‘Slave Market’ that had been organised as a carnival gag in Schwaz in 1967. It is so obviously influenced by orientalism but also suggestive of a racist mindset. There is, however, little context to why this poster has been put on display. The curator said it was to reveal to audiences something about the mindset of the collector, Chesi, which is admirable, perhaps, but I genuinely wasn’t sure what the point and purpose of this museum in Schwaz was. I wondered if it would serve its function most effectively if it concentrated it resources in returning all the objects its collector spuriously acquired and shut itself down. If it was a museum of the people, which people was it purporting to represent, and who was its intended audience? While on the one hand the newer, more critically reflective displays did allow for more questions to be raised, was it enough, or was it a way of sanitising its own history? How was the city of Schwaz continuing to profit from this venture?

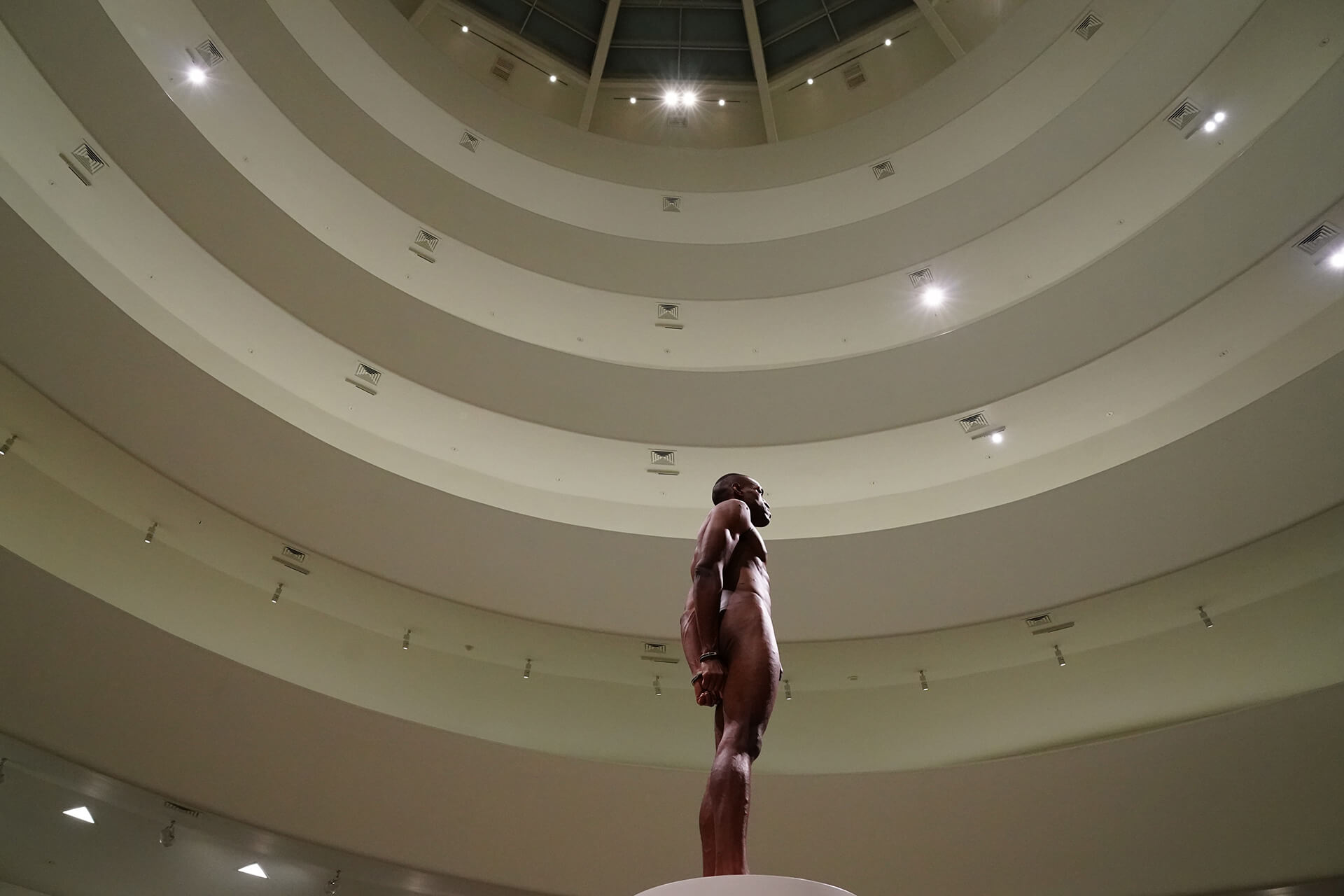

I thought later about the Congolese political activist, Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza, who has been provocatively advocating for the cultural restitution of African artefacts housed in European museums obtained during colonisation. In actively stealing choice artefacts from specific museums through live-streamed interventions with collaborators, he reveals the absurdity of whom the ‘law’ is meant to protect. The fact that he is stopped by security, fined heavily and even threatened with a prison sentence for attempting to take back something that never truly belonged to the museum in question and that rightfully belongs to African people speaks volumes about how European cultural institutions continue to profit from the thievery of colonisation. Through his demonstrations and the ensuing court trials, he questions the history that legitimised colonial occupation and the various losses that ensued for indigenous peoples. It is a burden he bears upon himself, much like a recent live performance by the Cuban-American artist, Carlos Martiel, at the rotunda of the Guggenheim titled Monumento II, in which the artist stood naked on a plinth on November 10 for several hours, his hands behind his back, his wrists handcuffed, the lighting dramatic enough to throw multiple shadows on the floor. It’s a performance that implicates every viewer in how it depicts the alienation of marginalisation. It draws its visual heft from historical images of slaves displayed naked to potential buyers at slave markets, re-invoking the traumas that remain inter-generational, unaccounted for, with no sense of reparation in sight.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Rosalyn D`Mello | Published on : Dec 10, 2021

What do you think?