Journeying Across the Himalayas spotlights the region’s layered society and culture

by Aastha D.Dec 14, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Alakananda NagPublished on : Jan 14, 2025

The temple bells of Manipur in Northeastern India have announced the raslila performance since its first iteration in 1779, as Angana Jhaveri noted in her PhD thesis. Nayana Jhaveri (1927 – 1986) was born to be a Manipuri dancer. All those who knew her and her work would agree that she didn’t just dance; she lived by the tenets of this dance form to the end of her life. The Jhaveri sisters and their guru, Guru Bipin Singh, were responsible for bringing this dance form from temple to stage.

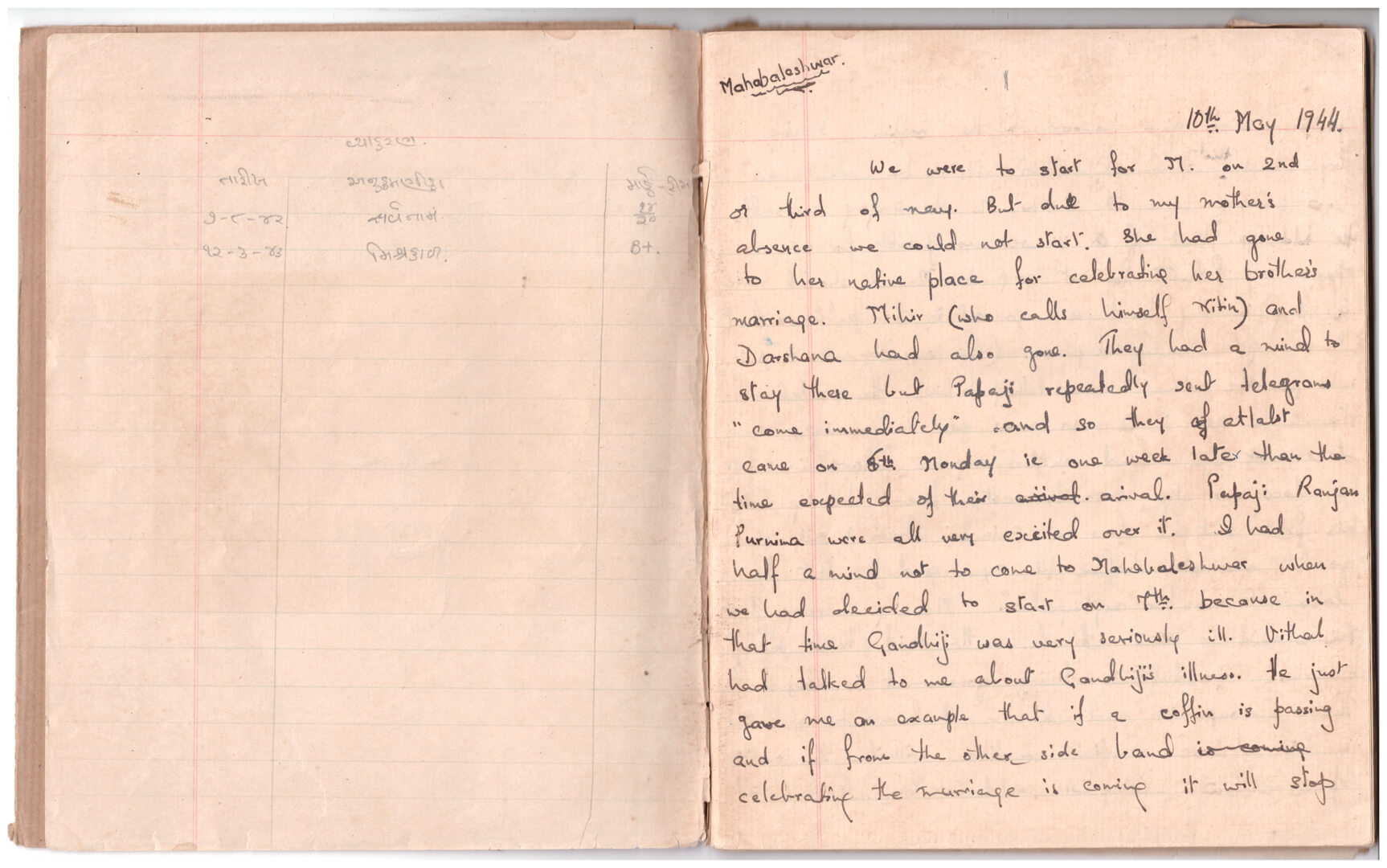

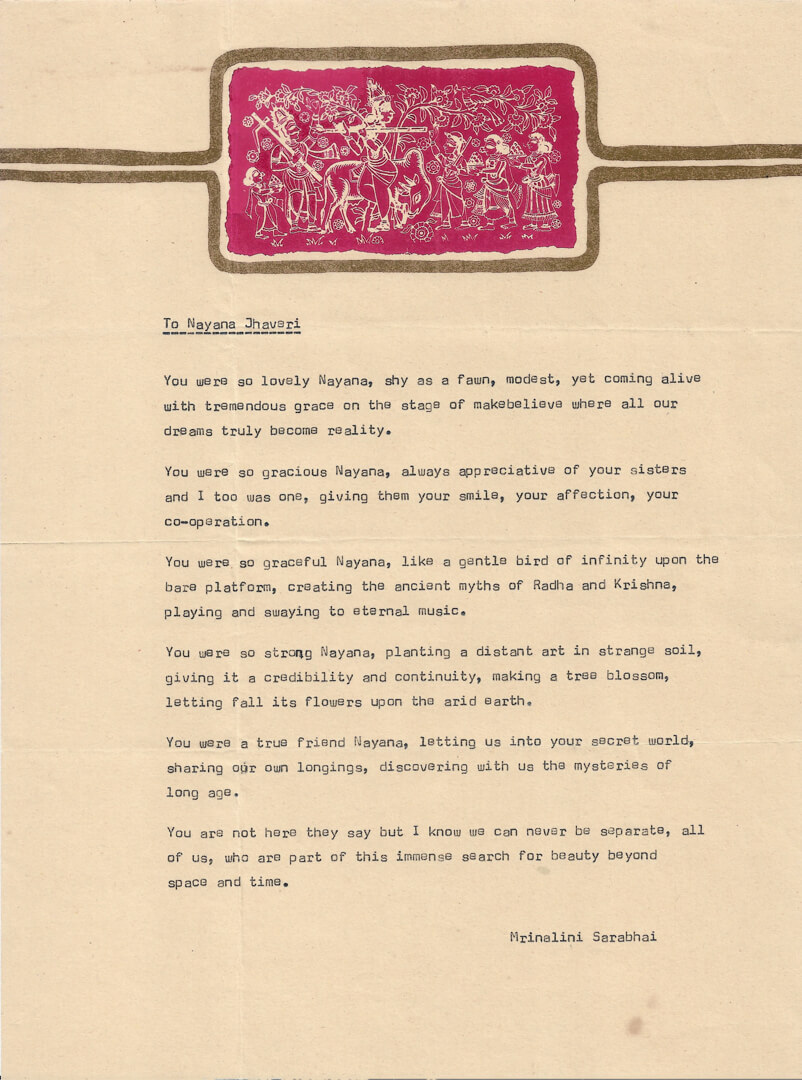

In the quietude of a Goan home, a trunk arrived from Bombay, from the home of Darshana Jhaveri, the only surviving sister. Its contents—letters, tour details, Nayana’s teenage diary, performance posters and photographs bore the history of the Jhaveri sisters—untouched, fragmented, fragile. These objects were about to be indoctrinated as the foremost contents of the Jhaveri Sisters Archive. “Where is this archive?” one might ask. It would be fair to say it is an entity as elusive as it is ambitious; its future contents scattered across formats and geographies—some unknown, some lost. But how are we to preserve what is lost? This question lies at the heart of Archival Matter, founded to uncover forgotten histories, ask difficult questions and make critical narratives accessible. By balancing academic research with artistic expression, we aim to approach these narratives with care—entering their silences, preserving their integrity and telling their stories in ways that resonate far beyond the archive.

Nayana Jhaveri founded the Jhaveri Sisters Dance Company, later joined by her three sisters, Ranjana, Suverna and Darshana. Together, they transformed a sacred practice into a global art form. Their story remains largely unknown today, with archival materials tucked away in bundles, obscured in lofts and jostled in steel cupboards in Darshana’s home, who single-handedly tried to preserve all she could. These objects speak not just of the Jhaveri Sisters’ invaluable contribution to Manipuri dance but also of the absences that punctuate their story—how does one enter their lives, connect the dots, know who they were and comprehend the depth of their legacy?

The core of this story lies in Nayana, the eldest of the sisters. Understanding her—and, by extension, Manipuri dance itself—requires unpacking the intersection of cosmopolitanism and spiritual practice that shaped their journey. In multi-ethnic, multilingual and politically layered Manipur, dance remained omnipresent through time. It finds you—in daily life, in rites of passage of birth, marriage and death, in temple celebrations and festivals. Dance is alive among the people in the community, coexisting with the classical tradition. 1950s South Bombay was a very different world from this, and the decision by four young upper-class Jain women to pursue dance as both a career and life philosophy was nothing short of radical. Manipuri dance, rooted in Vaishnav devotion, became their language of spiritual expression, actualised by Nayana not just intellectually but as a way of being.

They seamlessly straddled two worlds—the sacred and the secular. In the Shree Shree Govindaji Temple in Imphal, their dance was an offering to the divine, and on global stages like Lincoln Center in New York, it became a cultural bridge. Through their performances, they forged connections between indigenous traditions and the modern world, asserting agency, identity and cultural preservation.

Largely speaking, in post-colonial South Asia, the absence of structured archives carries an ever-present fear of scarcity stemming not only from historical neglect, wars and colonialism but also from a culture that has long privileged oral transmission. To add to this, across religions and mythologies, a belief persists: destruction precedes creation. While profound, this has perhaps had something to do with leaving preservation as an afterthought. In most cases, this carries the haunting possibility that nothing remains at all. Yet, this void compels reinvention, forcing a rethinking of what an archive can be. As a teller of these lost histories, every new work feels like stepping into an abyss—a disorienting confrontation with absence that has now become an essential, if unsettling, part of the process.

Against this backdrop, Darshana’s preservation of these archival materials is the exception. Angana Jhaveri’s words about her aunt resonate deeply: “All of Guru Bipin’s choreography is in her memory.” At 86, Darshana herself is an embodied archive. Before her, Nayana left behind her three sisters as the archive, passing on the dance, in movement, in expression, in form and in the expansive lives they lived.

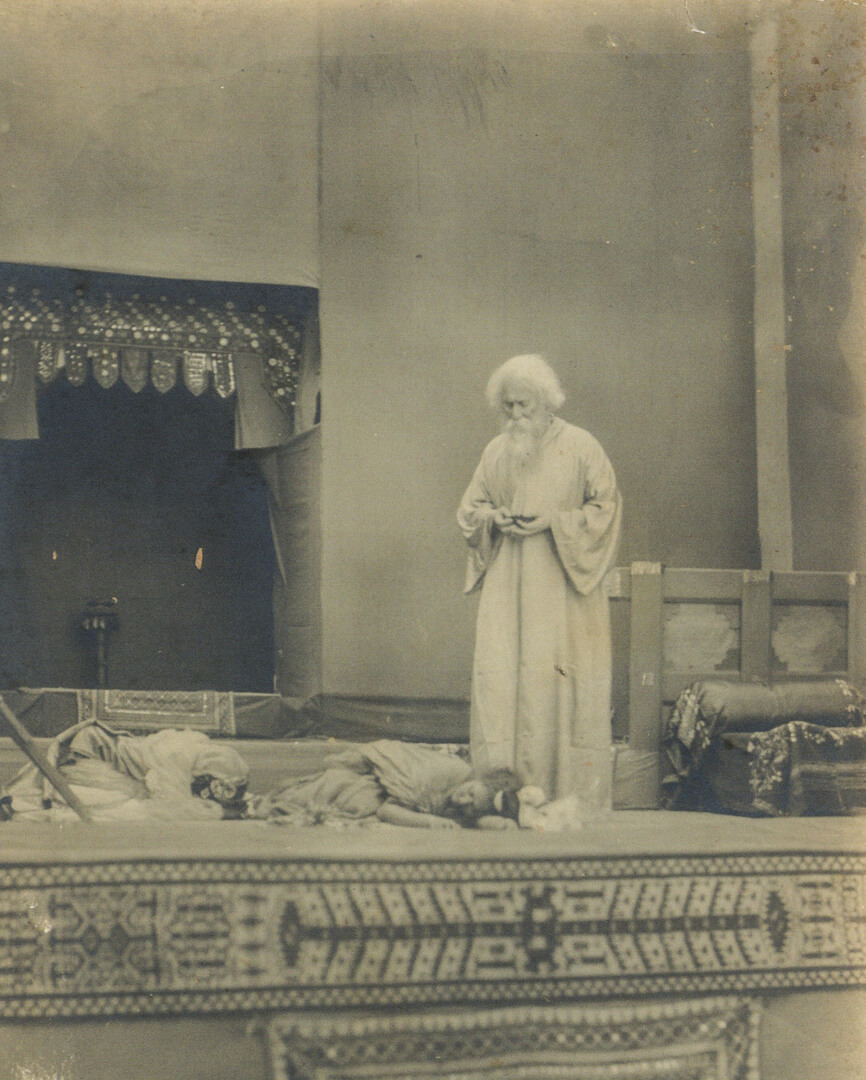

The Jhaveri sisters’ history cannot be disentangled from the influence of poet, polymath and first Asian Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. It was Tagore who first introduced Manipuri dance to the world, incorporating it into the curriculum of his Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan as early as 1919. Tagore’s vision for Indian dance in colonial India challenged the limitations of a repressive society so women could assert their presence as artists and individuals. In this transformative moment, Manipuri dance found a place of acceptance. Its portrayal of Krishna and the gopis through delicate, codified gestures aligned with societal expectations of modesty. Its elaborate costumes, with exquisite embellishments and voluminous skirts, dissolved the dancer into a sacred tableau, the dancer's body losing its identity. Manipuri dance then offered a unique pathway for women to occupy the stage while subverting societal norms, and women like the Jhaveris were able to make a significant impact and create history.

Why, then, is the Jhaveri sisters’ history absent from institutional archives? The gaps in their story are compounded by the challenges of preserving South Asia’s postcolonial artistic traditions exacerbated by bureaucracy, limited institutional support and an inconsistent archival culture. Important voices like women's stories are pushed to the margins, and countless histories have been lost.

Reconstructing their story relies on fragile materials from Darshana’s trunk and the memories of Darshana, Angana and Likla Lall, Ranjana Jhaveri’s granddaughter. Those bundles in cupboards in Bombay remain untouched due to logistical and financial constraints, pointing to the challenges of preserving such histories.

While institutional archives are critical to understanding our past, a world of possibilities, memories and interpretations lies outside of traditional structures of preservation, pedagogy and what is considered worthy of remembering. Much can be found in the unexpected, in guerilla fact-finding, quasi-inquiry outside of conventional methods, the question of authenticity hanging over us. It is critical to understand the extent of the loss and make every effort to preserve without prejudice and redefine the archive. The Jhaveri sisters’ archive challenges us to reimagine conventional approaches as we aspire to work toward a physical and digital home for the archive and a travelling exhibit.

The exhibition Nayana Jhaveri: A Life in Lasya unfolds in four movements: Manipuri philosophy and the Vaishnavite tradition; Nayana’s early influences in Tagore and progressive South Bombay; the sisters’ performative lives; and the echoes of Nayana’s legacy after her passing. The exhibition carries a film directed by Angana of her two aunts, Darshana and Suverna (who has since passed) in animated conversation, Nayana’s diary from 1944, a rare five-page scribble by Sushil Jhaveri, Nayana’s husband and the ensemble’s manager, capturing the reflections of famed Indologist Sylvain Lévi on dance, Nayana’s pictures as a teenager dancing the then popular Kandyan dance from Ceylon, poignant condolence letters and telegrams after her passing and more. The show debuted at the Goa Open Arts Festival in 2024 with the help of a generous grant from the Nazar Foundation and will travel to Arthshila, Ahmedabad, in January 2025.

Ultimately, the concept of lasya - the feminine form in the dance stood out. A thread that runs through Nayana, the dance form, the philosophy; a blending of rigorous practice and spiritual surrender. Lasya is soft, gentle and fluid even while it is restrained—a blending of rigorous practice and spiritual surrender. It exemplifies the longing of Radha and the gopis for Krishna's divine love: this quiet grace contrasts, yet complements, the acrobatic vigour of Krishna's tandava. On and off-stage, Nayana personified lasya in her practice, as in her life, steeped in devotion. The exhibition then had to be quiet and meditative. Its curation emphasises pause, reflection and immersion, leaving space for viewers to encounter the philosophy at the heart of the Jhaveri sisters’ work.

The trunk and this archive are incomplete but living, dynamic and mutable, and archives, by their very nature, are haunted by what they exclude, omit, and forget. The question then is, what is the archive?

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.)

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Alakananda Nag | Published on : Jan 14, 2025

What do you think?