Journeying Across the Himalayas spotlights the region’s layered society and culture

by Aastha D.Dec 14, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Feb 21, 2025

"Is this your first time?” This was a recurring question amongst visitors attending the opening week of programmes at the Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry; it was both a conversation starter and a quick index of art world positionality. Initiated by Sheikh Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah, and now helmed by his daughter, Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, the biennial is firmly embedded in the state machinery – with a sprawling complex of galleries and spaces in the heart of Sharjah. It also has the wherewithal to repurpose unlikely spaces through the emirate (and commission over 200 new works to populate them) – from vegetable markets to suburban clinics and fish feed factories. Yet the biennial also effects a convivial, if temporary, togetherness: from wide-ranging permutations of to carry (to carry a library of redacted documents/ to carry equatorial heat), proposed by its five curators – Alia Swastika, Amal Khalaf, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Natasha Ginwala and Zeynep Öz, to the structure of the opening week, where hundreds of artists, journalists, curators, patrons and visitors were bussed around in agreeable chaos, sometimes making long journeys from coast to coast in a single day.

Programming work across 17 venues, the five curators, selected by Hoor Al Qasimi for their engagement with South-South practice and exchange, framed the biennial as a “collective wayfinding, a modality of sense-making and insistent looking”, the works channelling this processual, sometimes unresolved, energy. At the Sharjah Art Foundation in Al Mureijah Square, New Zealand sculptor Michael Parekōwhai’s elaborately carved red grand piano (He Kōrero Pūrakau mo Te Awanui o Te Motu: Story of a New Zealand river) seems marooned in the centre of the room until it is activated by a pianist and a solo dancer who leaps into the air around the instrument and even rolls under it, his movements both a complement and challenge to the piano’s sheer mass and solidity. The underwater realm surfaces with works by several artists in another gallery, including veteran Bahraini painter Nasser Al-Yousif’s renderings of coastal scenes and pearl divers, Monira Al Qadiri’s arresting installation Gastromancer, where visitors hear whispered stories on gender by putting their ears to the bellies of two giant seashells in a circular alcove bathed in red light and Stephanie Comilang’s Search for Life II, which embraces the intimate voice of social media videos to craft an expansive ethnographic canvas of pearl diving across the UAE, Philippines and China. Comilang's work is structured around a wooden pier within the gallery space, with two video streams. A pearl diver in one of the videos tells the camera that a small pearl could net him a thousand pesos, once adequate for an astonishing range of commodities, including gold jewellery, a small boat, and even some food. His image is projected onto a massive video screen made up of individual strings of pearls – signifying connections between economies, markets and people, both materially and narratively.

The opening week featured several performance activations, some harder to access than others because of the logistical intricacies of staging live work in found spaces. The act of seeing can feel competitive and frenetic; you’re constantly jostling people to get to the front of the crowd, or standing on tiptoe to catch disconnected snatches of performance. Indonesian vocalist Rully Shabara’s midafternoon choir at Arts Square was a welcome change of pace – any coherence was found musically, not narratively – inviting audiences to soak in an absurd mixture of song and sound over time. On another evening, members of Bilna’es, a record label and publishing platform whose work supports artistic communities in Palestine, played a DJ set in the courtyard of the Al Qasimiyah School; their transitory audience included people making their way from one section of an exhibition to another and those determinedly bobbing their heads in time to the beats.

Embodiment was also central to archival presentations, like a room dedicated to the choreography (with some video documentation on view for the first time) and writing of the Indian artist Chandralekha, who drew on Bharatanatyam, yoga and the martial art style of kalaripayattu in her work and widely influenced the practice of a range of 21st century dancemakers, both in her insistence on drawing from native performance practices and in her interrogatory spirit – where the body was a medium for radical feminist inquiry. “The feminine principle is primal…because [of its primacy in] the entire creation and by creation I don’t mean procreation, I don’t mean giving birth to children, I mean the entire creation – like the entire vegetation, the nature, everything,” she says in the 2003 documentary Sharira: Chandralekha’s Explorations in Dance (directed by Ein Lall and on view at the biennial). The biennial commissioned Nyāsa, a new performance work by dancer and poet Tishani Doshi. A yoga practitioner, Doshi performed Chandralekha’s last work, also called Sharira (2003), with martial artist Shaji John, for 15 years. Sharira becomes a choreographic lexicon of sorts for her; she plays with movements, images and ideas from it in Nyāsa. Her embodiment of those images—a goddess, one palm pointed up to the sky with the fingers of the other opening out towards the ground, yet with her elbows welded too close to her torso to draw parallels to familiar images in temple sculpture or classical dance—situates her outside of conventional ‘dance’ narratives, perhaps a productive friction, in how she uses the non-linearity of poetic forms to structure choreographic phrases.

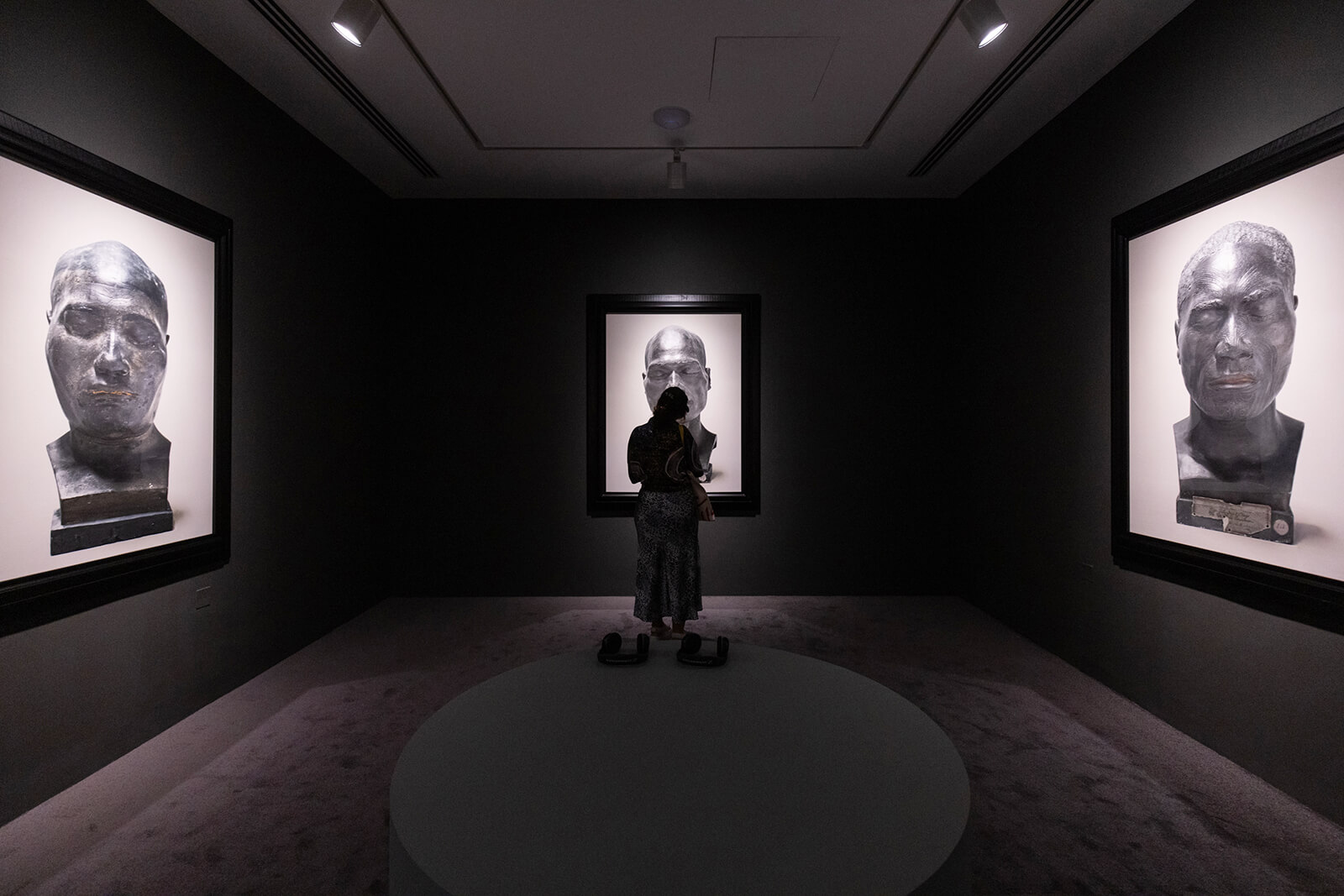

The body featured prominently in video works at the biennial, carrying histories of protest, performance and care through its motions. In Al Hamriyah, with two venues by the coast, a Yakthung (Limbu) woman travels back in time to shape the world via a tender exchange with an ancestor in Nepali artist Subash Thebe Limbu’s Ladhamba Tayem; Future Continuous (2023). Meanwhile, Luke Willis Thompson’s Whakamoemoea (2025) takes audiences into the future to 2040, 200 years after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, an agreement between the British Crown and Maori chiefs that defined their co-existence in Aotearoa/ New Zealand. In the video installation, Maori journalist and broadcaster Oriini Kaipara delivers a powerful monologue, recounting past injustices and abuses against Maori people and enumerating a constitutional transformation after the adoption of an Indigenous plurinational state in the late 2030s. This is poignantly speculative given the Treaty Principles Bill introduced in New Zealand’s Parliament in 2024, which runs the risk of undermining the Maori rights and privileges laid down in the 1840 treaty.

In a short season of major art world events in the MENASA region, the opening week of the Sharjah Biennial coincided with the India Art Fair in New Delhi and closely followed the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah and the Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial. Across stray exchanges through the week, there was a sense that biennials are increasingly ubiquitous, some with an emphasis on community and collective processes (making room for their dysfunction, including funding deficits and lack of access to key venues) – and also as instruments of soft power, with culture deployed to gild the image of authoritarian states – the conceit of ‘art’ vaguely gesturing towards the liberal and the secular in a world increasingly stripped of these notions. The opening speeches, including Al Qasimi’s emphasis on practices of solidarity as ancestral inheritance, gestured to overarching states of crisis and uncertainty, both in the Arab world and elsewhere. Negotiating the aesthetic and the political is a fraught act, as the biennial evinces; there are lessons to be learned, then, in persistent declarations of presence. In Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid’s Chibayish (2022), a young Ahwari boy from the wetlands of Southern Iraq whirls incessantly, voicing a monotonous refrain as he pounds the carpeted floor with his feet. The camera zooms into his sweaty face, its unsteadiness magnifying his delirious energy. In Rajyashri Goody’s Is the water chavdar? (2022), crowdsourced photos from the Google Maps entry for the Chavdar tank in Maharashtra, India, substantiate transgression and resistance as wet inkjet prints of visitors who bleed into their surroundings, permanently imprinting their once forbidden presence. In 1927, the economist and architect of India’s Constitution, Dr BR Ambedkar, led a group of Dalits (an umbrella term for several marginalised communities) in a protest against caste discrimination, drinking the water from the tank. Dalits in South Asia were often barred from using public space and community resources. Goody’s project was expanded from the book You’ll Know When You Get There (Natasha Ginwala with Ayumi Paul, Rajyasri Goody and Fazal Rizvi, YAZ Publications, 2024). Turning the show-to-publication pipeline on its head, YAZ takes the opposite route, with some of its 13 books now blossoming into exhibitions.

To watch Italian-Libyan artist Adelita Husni Bey’s Like a Flood (2025), a video installation unpacking the economic and cultural impact of a water crisis precipitated by the Italian occupation of Libya, visitors huddled inside cylindrical concrete pipe segments at the Kalba Ice Factory on Sharjah’s east coast. Libya's water scarcity is an ongoing issue, worsened by climate change, political instability and depleted groundwater reserves. How does one respond to a world in crisis? Inside the pipe, there was a prevailing restlessness; seated visitors found themselves sliding down against its circular contours, caught in an awkward interregnum between sitting – and giving in.

The Sharjah Biennial 16 is on view until June 15, 2025 across venues in Sharjah.

(The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR.)

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Feb 21, 2025

What do you think?