ADFF:STIR Mumbai 2026 promises a radical vision connecting cinema, space and city

by Jincy IypeDec 15, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Gautam BhatiaPublished on : Oct 03, 2025

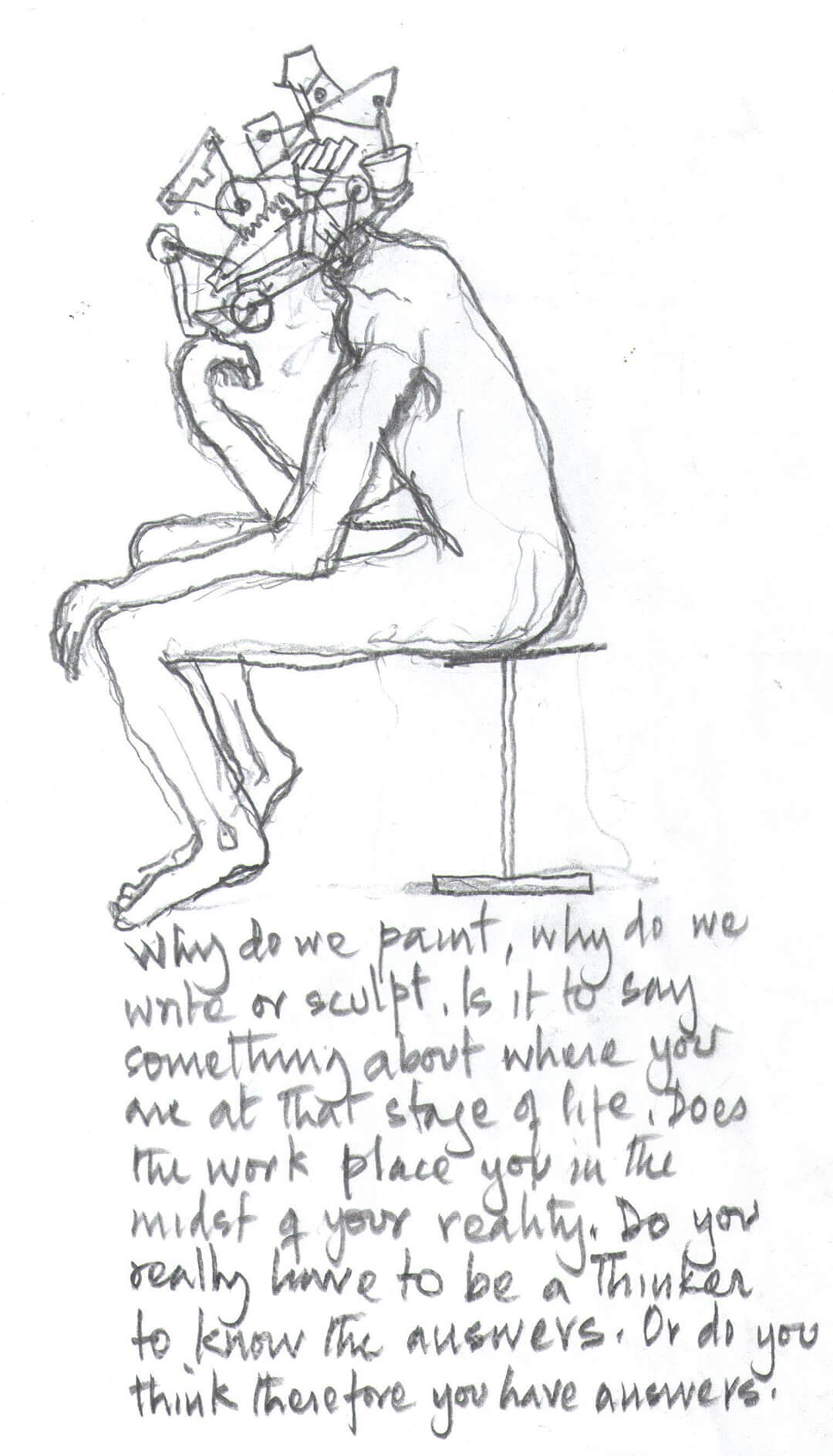

Are we living today in a time when clarity and focus have been traded for the half-baked, the ridiculous and the incoherent? An ever-present sense of defeat and despair lends a shrill, stagnant air to daily life. The morning news, the TV refrains, the fearful headlines, the statements, rebuttals and arguments – each day begins in a state of myopic hallucinations. What is real, what is fake, what is a mirage, is clouded in claims and counterclaims, rage and outrage. Every aspect of exaggerated reality is condensed into multiple oppositions.

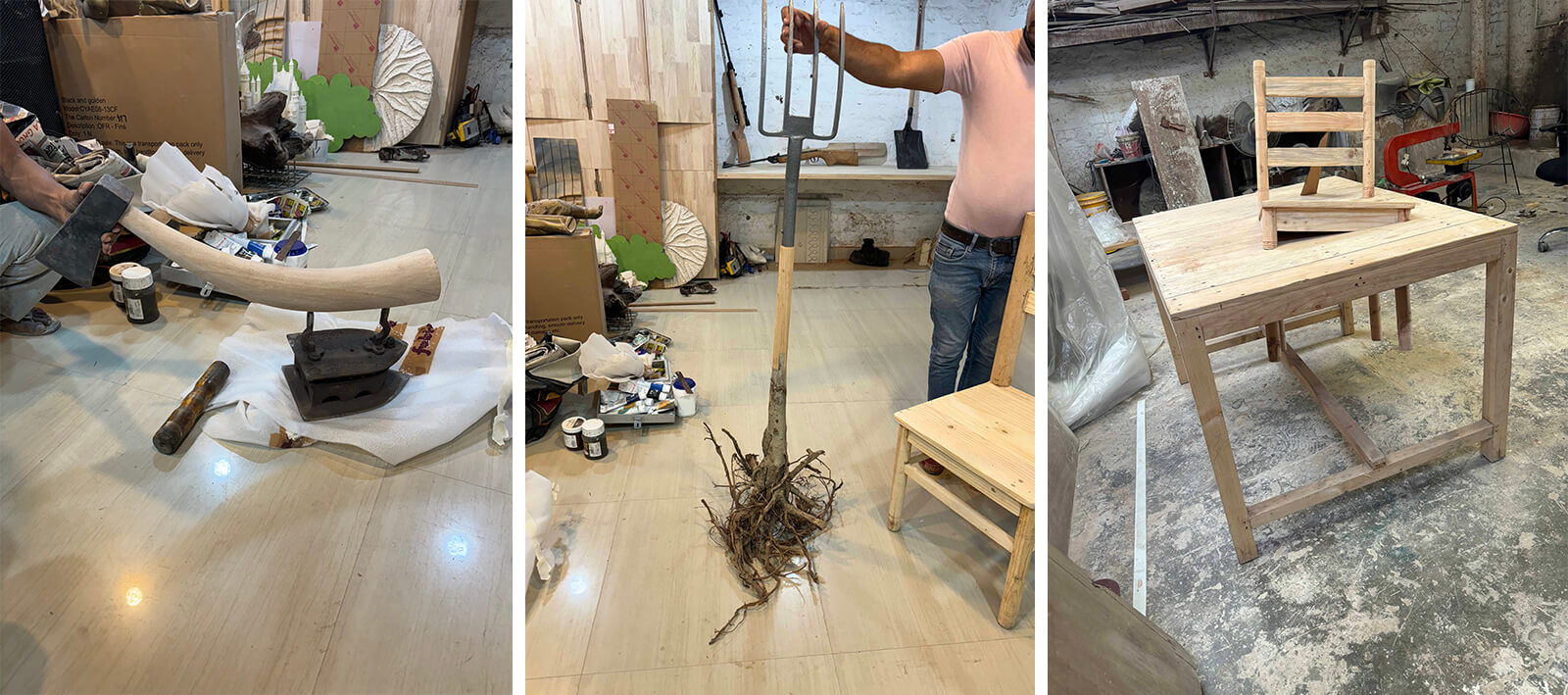

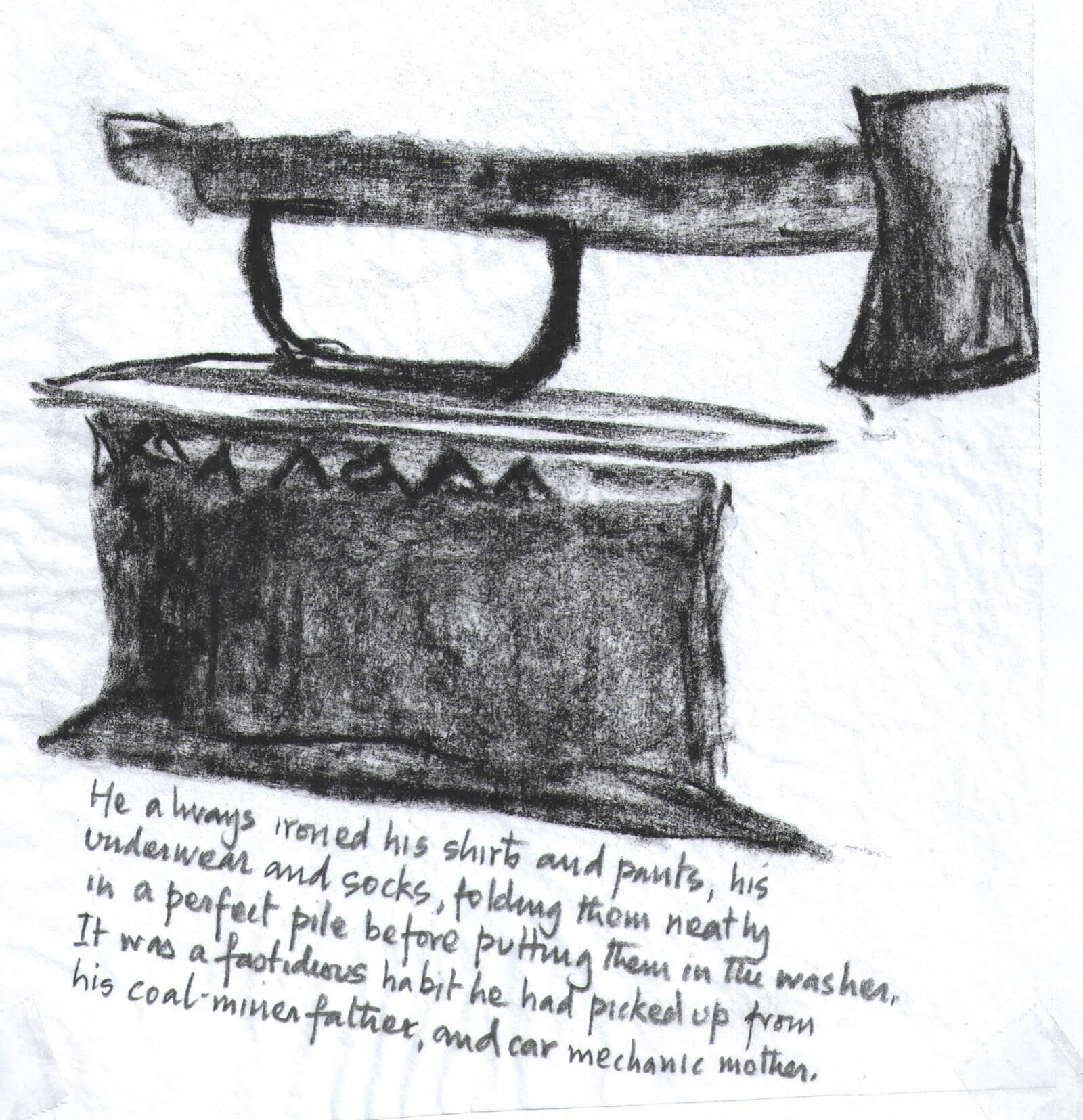

This two-faced world, entangled in contradiction – is it possible to place it in a physical context? Through a union of conflicting items, All the Beauty in the World examines something of its daily paradoxes—examining, so to say, the difference between an object’s original intent and its eventual form—between the individual object as noun and the dual object as verb. When daily items are absolved of function, they gain in new unintended meaning what they lose in usefulness. A cricket bat extends into a rifle; a clothes iron supports an axe as a handle; a chair merges with a table and another emerges from the root of a tree. When things are provoked into accidental fusion, obsolescence, exaggeration and subversion are but expected. Does the axe on the iron herald domestic violence? Does a rifle turn the cricket bat into a blood sport? Is the bicycle pump as thoughtful a performer of the trumpet as a musician?

What then of a camera that invades a private locker? When life expands its vortex of intrusion, insidious and invasive mechanisms are needed. The eyeball widens its reach with new forms of digital interference. Fingerprints aren’t enough for identification, so eyeballs are scanned and kept on file. Is the microchip in the brain the next step? Street cameras, surveillance packages available through private detective agencies, micro lenses in your locker, recording devices inserted on the tongue; people accept advancing technology, while still harbouring the hope of privacy. Everywhere, humanity’s darkest secrets are hidden in plain sight.

When the message is garbled and punctuated with politics and religious ideology, is it time to shoot the messenger? Working at the keyboard, the writer is the new literary assassin, too often marked by extreme views and constant denunciation. Journalism’s eloquence is lost to disharmony in a typewriter turned revolver, an instrument that is as much a communicator as a lethal weapon. So too, the village hand pump and hedge shears, both together, suggest the absence of daily utilities. No water, no electricity, no cooking gas. In a world of malevolent and incompetent deception, merely fixing the symbol of a potential provision is enough.

We give in so completely to contradictory moments of complete dereliction and utter beauty, sometimes in the space of the same day, in the shape of the same object.

Across the way, in the local park, a mother pushes the baby carriage across fresh grass on a cool, sunny spring day. In the evening, a sitar music concert draws the city’s cultured elite to the auditorium—life’s more blessed moments. The urinal inside the baby stroller is called Waste Management; the complete shower head and bath faucet on the sitar is called Water Music, not for any light-hearted meaning, but for multiple misreadings. Liberated from the stranglehold of simplistic function, the fused and confused object confronts new and unlikely connections, without script or plot. Is the environmental sign of a missing forest obvious in the rake growing out of natural roots, the tennis racket at the long end of a shovel, a signal to two kinds of labour? The misshapen root, the rake, the branch springing from a chair, the chair hovering in the space between table and floor, each starts as an object of design with a single and unique function, becoming utterly useless in the fusion.

You may well ask, then, is the fused object even a sculpture? Does it sustain an integral quality of form that keeps it in the realm of art? In developing the objects, the idea was to use ordinary things. Sculpture made from combining farm implements, musical instruments, kitchen equipment, toilet fixtures, baby carriages, water pumps, cameras, milk canisters, tennis rackets and typewriters (leaving out medical and industrial machinery, clothing and shoes) to suggest multiple situations and meanings. The despondent, the ordinary and prosaic, the beautiful, the melancholic – each stems partly from what the individual object stands for, and partly from the flux created by the fusion. The idea was to extract your own view from the mismatched combination. What do you draw from a coffee pot that pours its fluid into the stainless steel stem of a lamp? An electrical charge of caffeine—or just a dangling metaphor of two shiny objects in unfamiliar union. Maybe some things are beautiful as they are, and don’t need fusion.

There are, however, three ways of looking at the experiment. First, of course, is the experience of the known world of day-to-day objects—a hammer, an axe, a racket, a cello or a violin—each a facilitator of a recognisable function. They stay forever in their own agricultural, sporting or musical space, implementing with express purpose. As individual pieces, their meaning comes from our own understanding of their detached identity. Second is when their boundary and use get eroded, and they gain knowledge of the real world—its sinister aspects—and assume something of the character of their user and abuser. Does, then, this second world seem closer to us, truer to current attitudes and experience? For me, this exercise began as a minor play of the imagination, but over time it developed a plot of its own.

Third is the nature of the joint between objects. The handle of the axe and that of the clothes iron are the same; the bugle’s brass wind pipe turns into the water pipe for the tap; the stem of a stainless steel lamp becomes the metallic pour of a coffee pot. The seamless extension of one becoming the other belies its value as either a useful or symbolic object. Does the coffee pour out of the stainless steel pot and assume the flow of a stainless steel lamp? Does the brass bugle curl and extend its sound into the brass water faucet, the flow from one implement to the other, inexplicable? Without a joint, it is as if one object has morphed into another, eradicating the distinction between the same and the other. The camera’s penetration of the surface of the private locker is, by contrast, forced and violent, and indicates a tendency to deliberately disturb the locker’s secret intent. It is there, in the joinery, that the difference lies – less a slapping together of two disparate things, more an interlocking of different materials and substances in a careful crafting. I wasn’t so much searching for a continuity in the joining, as absurdity and incongruity, and the possibility that two unlikely objects will produce either an unexpected continuum or some visible confrontation—something laughable and stupid which, when the silliness settles, may turn morbid and menacing, or may not. Each composition was made in such a way that the pieces, however meaningless or however insightful, were still claimed by an order of aesthetics, by sculpture.

Certainly, right from the beginning, I was drawn to objects that were wholly dissimilar, those that would never be linked to each other in any conscious way. But I was equally struck by things that were closely associated with each other, like chair and table, tree and wooden furniture. Partly, there was a will to speak of the physical commonalities between different objects, something that makes fusion not just possible but effortless. Of course, in the conventional sense, it is hard to describe this as a craft or art, though the sheer skill of fusing the objects required exceptional care. The rifle is heavy steel and solid wood; the cello is an instrument of such delicacy and weightlessness that it made for an impossible combination. The rifle is an instrument in the wild; the cello is contained in a sound chamber. Do the two work together to produce a diabolical musical instrument?

Art often explores the paradox of goodness and wonder undercut by a tone of violence, ever-present and ever-lurking—in family matters, in relationships and in public life. The paradox follows us everywhere. We give in so completely to contradictory moments of complete dereliction and utter beauty, sometimes in the space of the same day, in the shape of the same object. The iron with the axe handle is not an all too subtle allusion to domestic violence, but such fusions do create the blunt message—a message all the more obvious when the axe is monumental and menacing. But blunt directness is the advantage of not disguising the objects into rendered pieces of sculpture, and using them as they really are. I often wondered if I had resurrected the fused objects in bronze, would they have lost their impact, the element of surprise that comes with their identification as real? Muddied by the medium they were clothed in, would they lose something of their message, but become better works of art? I knew then, they had to be real, things held, seen and heard, each describing its own ritual, things of our own time and geography. They had to be part of our cultural habits.

Though by itself, the object is static and capable only of the implied action set by its inventor, when combined with another, it tells a different story.

However ordinary and mundane, every object retains a reminder of its cultural roots, and reflects the stamp of its own time, its manners and conventions. Outside the classification of its function, its value as a tool or instrument, the object is also burdened with private associations and prejudices. Though by itself, the object is static and capable only of the implied action set by its inventor— but when combined with another, it tells a different story.

Sculpture can also be satire, with unfortunate proximities that tie together some other cultural or political malintent. We live today after all at the very brink of anxiety, constantly superimposing new hysteria over ordinary things, people, incidents and places. All around are the cultural dilemmas of an upturned world – a California restaurant serves the meat of rare and soon-to-be-extinct animals at exorbitant prices; a billion people have been lifted out of poverty during the largest ice-melt in the Arctic; the wealthiest city in the world still has the highest number of homeless and dispossessed. Surely such a wide, oppressive frame of conflicting references has to be reasoned with new possibilities. From the archaeology of stone-age tools—the hammer, the axe, the hoe, the pick, to those more advanced, including the rifle, the shotgun, the revolver, even the electric pot and pressure cooker—even if at a mere domestic scale, their eventual intent is to subjugate and contain, pressurise, pulp, suppress and eradicate. Objects that kill, degrade, decimate, muffle and unsound.

Such art, then, bids for an expression of dissections and incoherence that defies the order of existing identities and asks the larger question. If it is possible to splice an iron with an axe, a cricket bat with a gun, a water pump to a village, is it equally easy to splice a Hindu to a Muslim, a mosque to a church, a homeless person to a millionaire? Can Africa be fused with Europe? In a world where connections are local and continental all at once, where there is no longer any possibility of a homogenous neutral space, the idea was merely to hint at things, not to assign relevant meaning or demonstrate precise context. It is what a magician describes as ‘creative imbalance’, working on the edge of getting your secret discovered – the hope that an audience pins on the failure of an impossible act. When it fails, it is a serious tragedy and comedy. When it succeeds, it crosses an unknown frontier.

For myself, I had a less ambitious goal. I was looking for the object’s shifting position in the malleable boundary between twilight and darkness—that indefinable momentary period of change when borders merge seamlessly, and transit into a broader experience. The oddity of the combinations was critical to transforming the known into the unfamiliar. The juxtaposition of things with no known connection to each other lay in their extreme proximity – a unification whose eventual use was in its inappropriateness, and in the resulting dissonance that I hope suggests a discontent with common reality – a conscious attempt to lose control of our world, and escape.

Do then, the fused objects hint at old endings, or new beginnings, at familiar sights or strange places, common people or those with mutilated faculties and extreme habits? Is it in this conflicted, ambiguous purpose that the work finds meaning? Objects in denial, objects in dysfunction, objects in unrealised potential, objects in mistaken context and others in subverted identity, so to say, function without form, form matched by dysfunction, form in new form – All the Beauty in the World attempts to explore the contradictory reawakening of things that do not seem what they are.

The text is a provocative accompaniment to Gautam Bhatia's latest exhibition of fused artefacts, ‘All the Beauty in the World’, on view from October 12 – 17, 2025, at the Bikaner House in New Delhi.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 10, 2026

The Japanese designer's latest works, including As, bespoke lighting Nave and sculptural ladder Resonique, explore overlaps and mediation between materials and medium.

by Chahna Tank Mar 09, 2026

STIR speaks with the Latvian designer about his furniture practice and interest in introducing contemporary ornamentation as a storytelling technique.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Mar 06, 2026

An exhibition by London-based Superflux at the Weltmuseum, Vienna, considers the vital role of craft and craft thinking for our precarious present and derelict future.

by Domus Academy Mar 02, 2026

Presenting the Master's in Design Futures and Design x AI, two innovative pathways to train leaders capable of shaping future scenarios, between speculative vision and ethical AI.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Gautam Bhatia | Published on : Oct 03, 2025

What do you think?