A London exhibition reflects on shared South Asian histories and splintered maps

by Samta NadeemJun 19, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ayca OkayPublished on : Mar 09, 2024

Htein Lin, a multifaceted artist from Myanmar is renowned for his diverse practice of painting, installation, performance and writing that together epitomise a profound odyssey characterised by resilience, creativity and dedication to social change. As a self-taught artist, he has navigated his career through tumultuous times, making bold decisions that defined his trajectory.

Born in 1966 in Ingapu, Ayeyarwady Region, Myanmar, Lin's formative years were immersed in the turbulence of political upheaval. While studying law, he became actively involved in student politics, which became the "8888 Uprising," (also known as the People Power Uprising and the 1988 Uprising) after massive demonstrations in Yangon (formerly Rangoon) on August 8, 1988. The protests, rallying against the Burma Socialist Programme Party which governed the country as a totalitarian one-party state under the leadership of General Ne Win, quickly spread nationwide. During this time, Lin confronted the harsh realities of opposition to military rule while pursuing his studies in law. The uprising concluded on September 18, following a violent military coup orchestrated by the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). While Burmese authorities estimated the death toll from the uprising to be around 350 individuals, thousands of deaths have been ascribed to the military's actions during this period of unrest.

Forced underground following the military takeover, Lin spent two years in a refugee camp on the Indian border, where he honed his artistic skills under the tutelage of Mandalay artist Sitt Nyein Aye who was actively engaged in the anti-dictatorship campaign in Mandalay throughout the 8888 pro-democracy movement, notably by publishing the anti-junta journal Red Galone. Sitt Nyein Aye persisted in combating dictatorship by producing paintings advocating democracy and human rights. Lin’s move in 1991 to the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF) (Northern Branch) student rebel camp at Pajau on the Chinese border was marred by detention and physical abuse at the hands of a rival student group, underscoring the perils of dissent in Myanmar's political landscape, about which he has written a harrowing memoir.

Having escaped across the border, been captured by the Chinese authorities, and handed back to the Myanmar military, Lin returned to Yangon in 1992 and completed his law degree amidst ongoing political repression. However, his aspiring acting and art career met with adversity yet again when he was unjustly arrested in 1998 and incarcerated for nearly seven years on spurious charges. Yet, within the confines of prison, Lin's artistic ingenuity flourished. Utilising everyday items like bowls and cigarette lighters instead of conventional tools, he created striking paintings and monoprints on the coarse canvas of his prison uniform, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit amidst adversity.

Lin, a pioneer of performance art in Burma, has always defied oppression through creative expression, even performing for fellow inmates in prison. On May 5, 2005, his street performance with visual artist Chaw Ei Thein, titled Mobile Art Gallery and Mobile Market, sparked another military interrogation and highlighted the challenges of artistic freedom in Myanmar. The performance aimed to depict inflation and government censorship, by selling goods and showcasing art without permission in Yangon's streets. Payments were made in old Myanmar currency featuring historical figures. This led to their arrest and three days in police custody, which ended only when the police turned to them, as captive artists and asked them to draw ‘photofit’ portraits of a potential suspect in a deadly bombing which had taken place on May 7, since the description provided by a witness, when fed into the photofit software, kept churning out Western faces.

After a time away from Burma, in 2013 Lin embarked on several ambitious projects which generally combine found materials, memories, stories and traditional beliefs. One major opus is the multimedia installation named A Show of Hands which comprises hundreds of plaster sculptures taken from the hands of former Myanmar political prisoners, often made in a public place. Each sculpture is accompanied by a card containing details about the circumstances surrounding the individual's imprisonment and a video pulling together the commonalities and differences in their stories of detention. By capturing the experiences of former political prisoners through participatory performance and documentary art, A Show of Hands enables every individual to metaphorically ‘raise a hand’ and be acknowledged as a member of the extensive community of individuals who have endured human rights violations. The artist intends to continually augment the installation by incorporating new casts as detentions persist. The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma (AAPPB) estimate over 26,000 have been detained since the February 1, 2021 military coup.

Lin, represented by River Gallery in Yangon and Richard Koh Fine Art in Singapore, has been a prominent figure advocating for freedom of speech and human rights in Burma. In a conversation with STIR, the artist elaborates on his artistic practice, storytelling, collaborative approach and more.

Ayça Okay: Your journey as an artist is deeply rooted in your upbringing in rural Myanmar. Can you share more about how your childhood experiences and early interest in art shaped your identity as an artist?

Htein Lin: I grew up in a small village, surrounded by nature and traditional culture, where my father owned a small sawmill. There needed to be formal art education available. As a child, I enjoyed drawing, storytelling and making jokes. I learned to use the materials and inspiration in front of me. Since then, I have always found a way to make art, no matter where I am, whether that is performance, painting, sculpture, music or writing.

There was no university-level art degree in Myanmar at the time and there were only two government art schools, catering to traditional views of art and painting. Based on my marks in the tenth-grade matriculation exams, my grades were too high for art but too low for medicine, so I had to study law. That's the kind of education system we had. I wasn't looking forward to being a lawyer for my whole life. Some of it was interesting—and proved helpful in later life when I ended up in jail—but mostly, it was boring. However, at university, I stumbled upon an artists’ association and a group focused on traditional theatre performances. These shows, called anyeint, included female dancers, music and comedians. These satirical and slapstick performances were quite popular during the colonial era when they often carried political messages about our independence movement. We tried to revive that spirit in our shows and were coached by famous comedian and dental student Zarganar (Maung Thura), who was a couple of years older than me. He was told that the dictator Ne Win quite appreciated his jokes, even though they targeted his Burma Socialist Programme Party.

Participating in these performances at the university fuelled my interest in performance arts and I stayed engaged with the arts throughout my time at the university. When I eventually graduated, I abandoned law and started acting and painting.

Ayça: Your journey has taken you from the confines of a prison cell to the global stage, with exhibitions and performances around the world. How has this exposure to diverse cultures and audiences influenced your artistic practice, and how do you navigate the complexities of representing Myanmar's political landscape to an international audience?

Htein: Wherever I am, I try and capture the essence of my surroundings, whether that’s selling canal water at the Venice Biennale, painting How do you find Belfast? (2009) with soil from the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim, making portraits with sand from the Ayeyarwady delta, or making a funeral wreath in Insein Prison out of the lists of parcel contents which had been written out by the prison official who a bomb had killed in the parcel office.

When I travel outside Myanmar, I like to visit museums, sculpture parks and biennales and get ideas for how we can do the same in Myanmar one day. The Seven Decades exhibition I curated in the colonial Pyinsa Rasa Art Space the Secretariat building in Yangon in 2018 which featured artists interpreting the 70 years since Myanmar’s independence was the closest we have yet got to a major Myanmar contemporary art retrospective. This was held in fitting surroundings, the compound where our leader, former PM Aung San was assassinated in 1947 just as Burma gained its independence. For that, I created an accompanying timeline which went beyond the simplistic political narrative that the international community have of Myanmar which is a little more comprehensive than the Independence in 1948, followed by the military coup of 1962, the 8888 Uprising and Aung San Suu Kyi serving as the General Secretary of the National League for Democracy (NLD). Our multiethnic, multifaith country has faced complex political challenges from inside and outside for decades, contributing to the current crisis.

Ayça: Your artworks often explore themes of memory, identity and resilience, drawing inspiration from Burmese culture and history. Can you speak to the significance of these themes in your artistic practice and how they reflect your personal experiences and observations of Myanmar's social and political landscape?

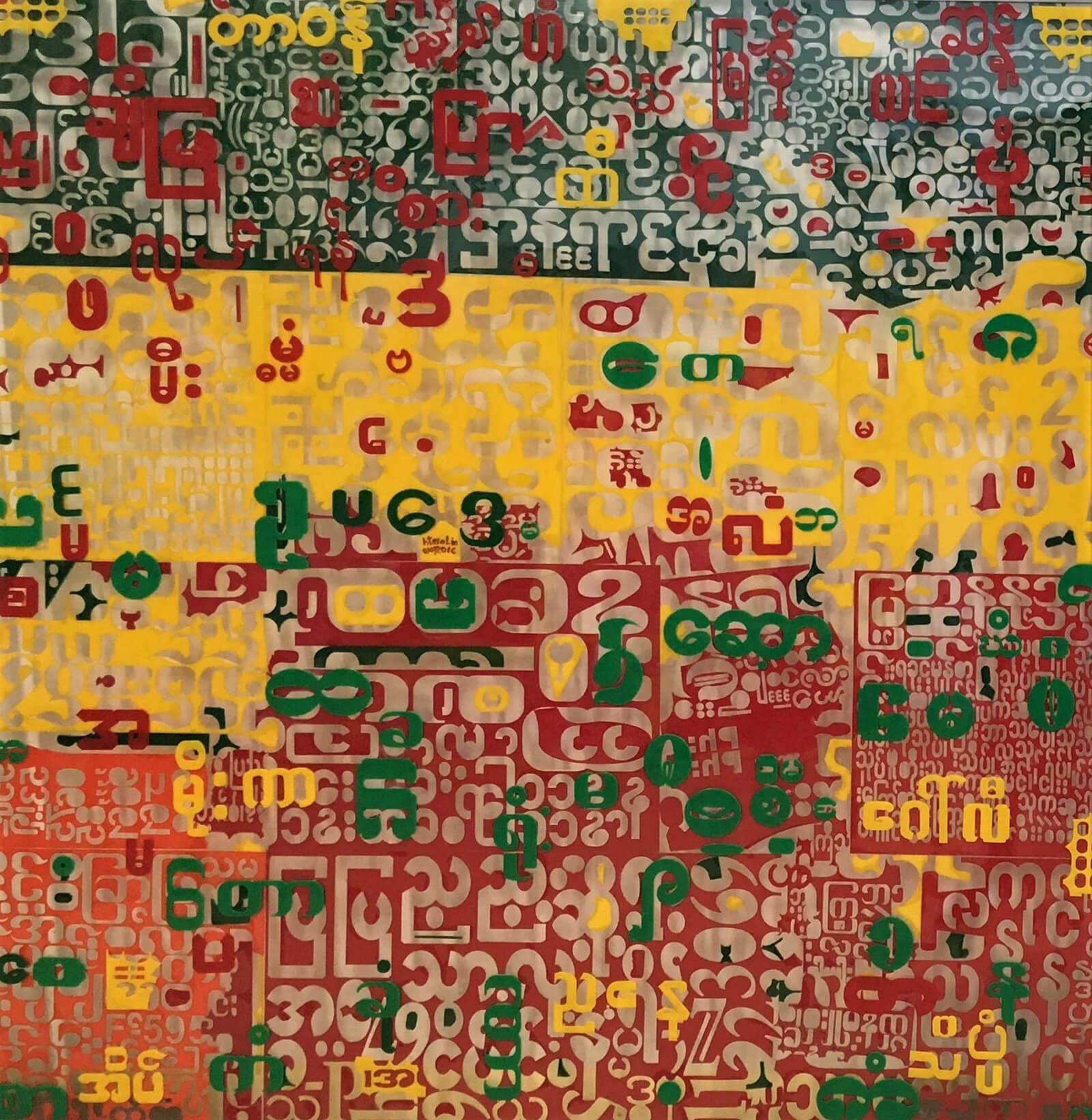

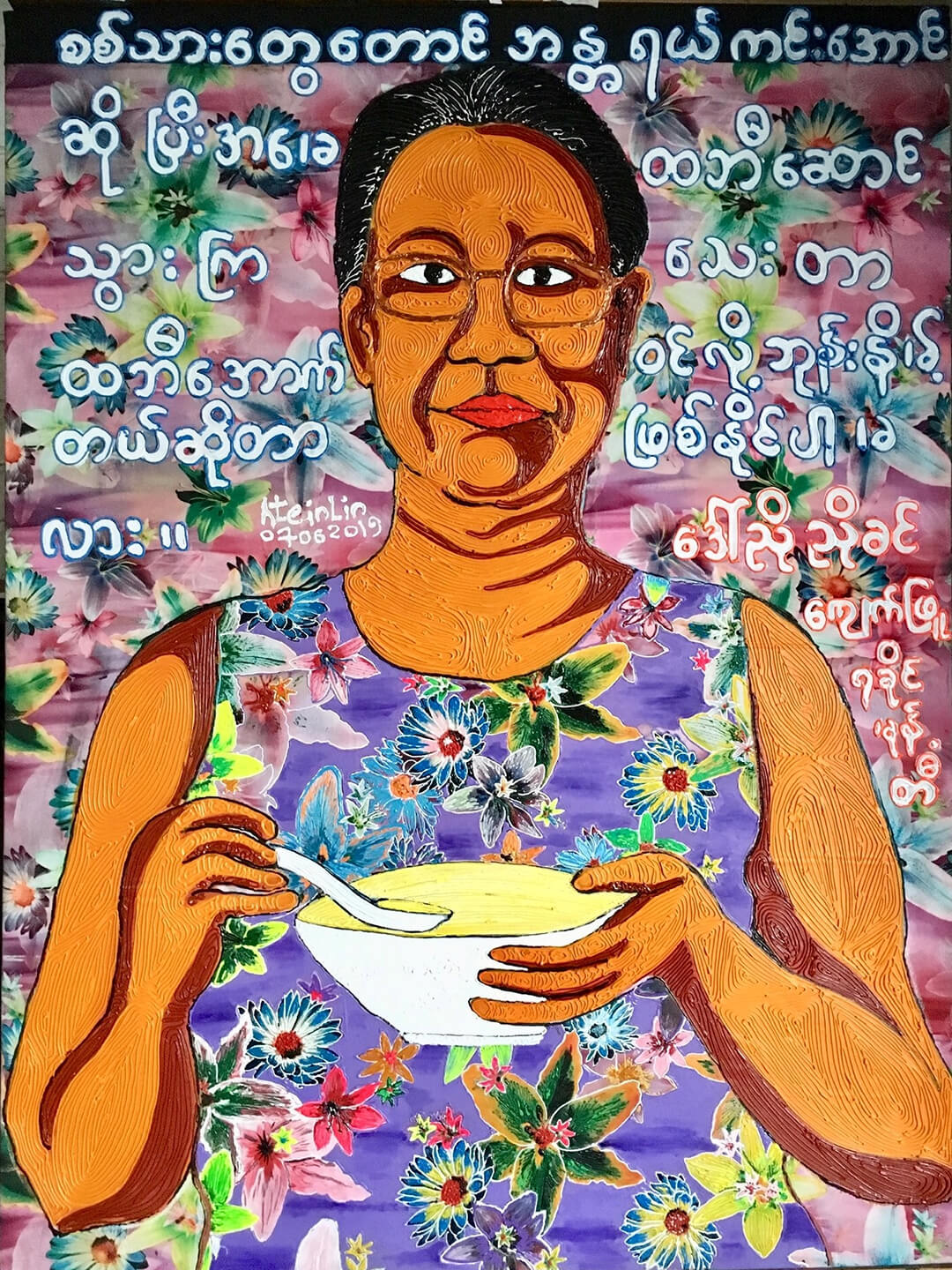

Htein: I like to tell stories and portray the views and experiences of others. A Show of Hands captured several decades of political struggle and hundreds of years wasted inside jail of men and women from different generations. My Skirting the Issue series asks women of various ages, classes and backgrounds how they feel about the taboo of mixing men’s and women’s clothing in the wash. I portrayed them on the old skirts they gave me and their varied views. I rescued acrylic scraps from the old signwriters in Signs of the Times. The letters have been cut out but the gaps leave a message. My Recycled series uses cardboard created from recycled paper. On it, I illustrate words in Myanmar that resonate with me, such as peace, Rohingya, corruption and red tape. I’ve also recycled our disappearing wooden wagon wheels into sculptures. I also like to seek out humour wherever I can. Humour and art are what make me resilient. We still tell jokes to resist, just as in colonial times with performances.

Ayça: What were the challenges and experiences you faced while advocating for democracy in Myanmar, particularly considering the limitations of understanding democracy under the military junta, the setbacks encountered during periods of activism and your journey, including time spent in prison and in the jungles along the Indian border?"

Htein: In the age of social media, it’s easier to protest and advocate for causes and there is more information and debate. Back in 1988, we were less informed. While we demanded ‘democracy,’ we didn’t understand what it meant. We were used to a one-party socialist system. Most of the books we had access to were either official state propaganda or underground Marxism. I headed to the jungles along the Indian border in 1988 to join the ‘revolution’ but ended up struggling to survive in a camp, training for ‘armed struggle’, armed mainly with a typewriter and bamboo sticks. When we went across to Pajau camp on the Chinese border, I was caught up in an interfactional struggle between student leaders and almost died. Over 30 were killed and I spent months in shackles being tortured. Then, between 1998 and 2004, I was imprisoned under the military regime. Throughout my time in the jungle and jail, I tried to pursue my art by improvising within a constrained environment. Part of the creative process was finding ways to make art even when I was prevented from doing so. When shackled and forced to paint flags for the jungle revolution, I painted the fighting peacocks going in the wrong direction. I painted the Torture Phone series in 2021 as a warning to the next generation pursuing armed struggle.

I learned more about democracy when I lived in the UK and discovered what is needed to make a democratic society function. We are a long way off from getting there in Myanmar. Following the November 2020 elections, another military coup took place in February 2021 and the military then brutally suppressed the demonstrations against it. The aftermath has claimed countless lives from all sides and plunged Myanmar into a civil war. It seems like the cycle keeps repeating itself. The military promises elections and reforms but doesn’t let go of power. And I went back to jail for three months in 2022.

Ayça: How did you enter the international art scene in London? How did the global exposure shape your artistic practice and perspective?

Htein: I moved to the UK in 2006 after marrying the former British Ambassador to Myanmar (2002-2006), Vicky Bowman, whom I didn’t expect the first time I saw her. That was when I was in jail in 2003. We, prisoners, read about her in the government newspaper, presenting her credentials to the Senior General and we disapproved. Coincidentally, she first saw me in the government newspaper in 1992 when the military held a press conference about our terrible experience in Pajau, which she disbelieved.

My first solo exhibition in London was at Asia House in 2007. Titled Burma Inside Out, it showed the 000235 painting series I had secretly created in prison and smuggled out regularly. Some of these paintings were featured in my recent Singapore show, Reincarceration. 000235 was my International Red Cross prisoner number. The series used found objects such as cigarette lighters and pill bottle lids to create marks and monoprints on the prison clothing. It depicted scenes of prison life and scenes of the world outside and the world inside my head. The show was on the cover of the English-language newspaper International Herald Tribune. Art critic John Berger visited it and even mentioned me in his book From A to X published in 2008.

While living in the UK, I continued performing art while connecting with the Beyond group in Belfast and artEvict in the squats of London. My favourite museum is the Tate Modern and it’s still my ambition to show my work there. The closest I have gotten so far is that my name features in one of Tate’s acquisitions, The British Library (2014) by Yinka Shonibare, a series of 2,700 books with the names of culturally significant immigrants printed in gold on their spines.

Seven years living in the UK allowed me to participate in international events such as the Venice Biennale and travel widely in Europe and Asia. Unfortunately, I am stuck in Myanmar at the moment.

Ayça: What can we expect from your upcoming projects and how do you envision using art for dialogue, healing and social change in Myanmar and beyond?

Htein: I am currently working on several projects. I continue to capture scenes of the current crisis on large pieces of cotton, using the monoprint technique I developed in jail. I am also exploring the world of spiders in sculptures made of recycled materials. We are planning a sculpture park at our farm in Pindaya, Shan State. The symbol of Pindaya is a spider. Local legend states that seven princesses bathing in the lake were captured by a giant spider living in Pindaya caves and had to be rescued by a brave prince with a longbow. But my spiders are more like the hardworking ones that the Scottish King Robert the Bruce (also known as Robert I) took inspiration from than Prince Kummabhaya aimed at. Robert the Bruce was said to have watched a spider repeatedly attempting to spin a web, which inspired him to never give up in his fight against the English. We need to cherish spiders like that in Myanmar.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ayca Okay | Published on : Mar 09, 2024

What do you think?