Sandra Vasquez de la Horra: Soy Energia links our bodies with our natural contexts

by Mrinmayee BhootJan 15, 2026

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Feb 29, 2024

The construction of the homeplace, however fragile and tenuous, had a radical political dimension...One’s homeplace was the one site where one could freely confront the issue of humanisation, where one could resist.

– bell hooks, Homeplace (A Site of Resistance), 1990

The very essence of the word home allows it to take on many different meanings. A place of refuge, of belonging, of dwelling. A place of resistance, of unsettling, of violence. There are as many ways to define a home as there are to name it. Each offers a nuanced reading of the home and prompts questions of care, of longing, of labour. Of the right of people to call a place a home, an issue magnified by the immigrant crisis in many European countries.

Unspooling the many ideas of what a home is, and what it represents, an association of female spatial practitioners, Matri-Archi(tecture)’s installation Homeplace - A love letter reimagines a public space at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; the Rotunda as a place of gathering. The interactive installation, on view till March 24, 2024, invites visitors to sit and reflect on the spatiality of dwelling and the meanings we attach to home. Designed as a 16-metre high beaded curtain which acts as a signifier of homeplace, it asks one to consider what memories a home might invoke. The layering of textiles, sound and storytelling allows them to create an affective space, and at the same time intimate. Through the minimal, translucent spatial design that activates the rotunda, thoughts on the intimacies of belonging and the socio-political forces that dictate it are suggested.

The designers use strategic spatial storytelling cues to explore commonalities of the home across cultural differences. Explaining the name for the large-scale installation, they state, “[Homeplace] can be understood as a set of conditions that are continuously being (re)shaped and (re)defined by a global majority nestling in the diaspora; the many of us who straddle multiple lifeworlds across spatial and temporal borders.” The design, nothing more than a bench, some voices, and a curtain is the collective’s invocation of an imbizo (a gathering in Zulu) and explores the ideas of home as a place (physical) and site (metaphorical) where negotiations of fellowship, of the resistance offered by communion come through.

What goes into the making of a home, and who makes it? How is home lived? These are crucial questions for communities that are estranged from their homelands. For them, the home becomes a way of saying we are here, that this is where we dwell. On the relevance of the homeplace, a space that allows reflections on the nature of “care and nurture, of resistance, redress, and transformation embodied in Black performance and everyday practice,” STIR talked to Khensani Jurczok-de Klerk, founder of Matri-Archi(tecture).

Mrinmayee Bhoot: What do you think about when you think about the idea of home or a homeplace or a homeland? Do you think these ideas are interchangeable or do they mean different things?

Khensani Jurczok-de Klerk: The notion of the homeplace is something that's been prepositioned by bell hooks, a black feminist scholar working within the field of cultural practice. For this project at Matri-Archi(tecture)—we are a team of five, myself, Abdé Batchati, Aisha Mugo, Afaina de Jong, and Margarida Waco—we came together and read this text. In doing that, we recognised that whilst hooks writes from the field of cultural practice, the argument provides a spatial cue, and as architects and spatial practitioners, we asked ourselves how we could work with this notion.

In our interpretation of the home place, it became clear that it is not fixed in time, scale, size, or state. It does not necessarily refer to a physical place, while it does have physical connotations. Hence, we started to think about the curtain that divides the kitchen. You’ll see this detail across so many different geographies in the African continent, across the Global South, and even in northern geographies like Italy. The curtain is a sort of protective surface between the kitchen and the lounge that allows for a certain kind of gathering to take place. And the homeplace is—at least in the way that bell hooks writes about it—a form of fellowship, of commune. It's a place where you can go to recover, to rest, and to affirm yourself.

It's funny that we were doing this at the commission of the Pinakothek der Moderne and the Architekturmuseum der TUM where the homeplace became an even more difficult notion to work with given the linguistic differences. The translation for homeplace we worked with in German was heimat (homeland), but homeplace doesn't necessarily mean your homeland. It was fascinating to see how there are so many dislodgements, and forces of unhoming at play when it comes to constructing a home, a common observation today. We see racialised women across the world construct homes as they move through the world, and that's what we're trying to get to in this, that in fellowship, the homeplace is created and then the conditions are specified.

Mrinmayee: One thing that struck me about how hooks writes about the homeplace was the idea of resistance. And I was wondering if you could talk about how you interpreted that in a spatial manner through your work.

Khensani: For us, the idea of resistance was clear, since we're working in a space in the Pinakothek called the Rotunda. From the images, you'll see that it’s a very intimidating space, white, of course, with a very typical sort of art museum and gallery typology. In the museum, there's no seating place that you can sit at without needing to consume something. So if you want to sit down after seeing one of the exhibitions, you have to go to the café, you have to pay money.

So we thought to ourselves, not only is that an aspect of inaccessibility, but there's also the aspect of discomfort for people who might want to rest and contemplate in between. When we think about the homeplace as a site of resistance in spatial terms, we were also prompted to use that as a cue in creating this resting place in the centre of the foyer.

So when you arrive, there's a place to contemplate. It’s not that explicit but in a sense, the art installation is resisting the controlling dominance of that rotunda space, which can be very intimidating. We asked, what does it take for someone to dwell in a space that is typically intimidating? And we thought that this was a response to that.

Listening is the key act to recognising the transgressive role of narrative for those in subaltern positions, where the story contains both the idea and the spatial model. The repeated refrain acts as a form of spatial knowledge to reinforce, construct, and engender particular kinds of spaces. – Huda Tayob, Transnational Practices of Care and Refusal (2021)

Mrinmayee: I was also wondering about the idea of dwelling: dwelling within the home or dwelling in a public space like the Rotunda, are there any juxtapositions or relationships between the two we could look at here? Are there any storytelling cues you used to construct your project?

Khensani: It’s something we carried with us throughout the design process as a team. Our team comes from very different geographies, so when we were discussing home, many different signifiers came up. The curtain was the biggest cue that in a way suggested an archetype. Unlike the door, the curtain presents more of an open invitation. The door presents no possibility for any gathering happening inside of that space to determine its condition without entrance.

Whereas the curtain is something that allows us the possibility of entry because of its translucency, even sometimes because of its sound. It allows for a person who would be approaching that space to announce their presence and for the fellowship inside of that space to decide if it will be an open invitation. We also recognise that sometimes the fellowship inside of the kitchen is moms and aunties productively gossiping, therapy sessions, of a sort taking place, which can be protected because there's a curtain and not at all. So, with the positioning of the installation, we are thinking about the spatial performance of that archetype.

One last point in terms of signifiers of home is the beads themselves. We designed these beads, which was a fun process. They signify the different artefacts that construct a home because we thought to ourselves, what are the things that people use to self-organise and create a home? How can we depict that? This resulted in a series of workshops where we collaborated with an incredible group in Munich called AfroDiaspora 2.0. Discussions within our group led us to think about things like the calabash. We asked ourselves, what are the things that you use to welcome, to celebrate, to recover, to signal a sense of return?

So there are things like the fufu stomper which is a cooking utensil, or the pop spin. Hence, the beads are a combination of those artefacts that people take with them when they move through the world and try to construct a home. It's like calling upon flavours, or certain smells that signify that you are now in your place.

Mrinmayee: In the description, you have talked about the use of soundscapes for the work, so could you elaborate on the kind of stories you wanted to position while using these voices, and what they add to the experience of sitting in the interiority of the beaded curtain, listening to it?

Khensani: It's one of the components of this art piece that is the most sensitive in that it also demands whoever visits the rotunda to sit down and listen. It activates a sense of deep listening. You can't fast-forward the voices. In that way, it's an invitation. The reason that we incorporated the soundscape was to add another emotional dimension to the homeplace, particularly within the context of a museum that deals with architecture and form rather than emotion.

We also wanted to highlight the social components of what these forms tend to carry with them. Another reason to include the voices was that the free space of the rotunda serves as a brilliant place for people to sit with these stories. We invited a variety of people—mostly from diasporic communities—to share their interpretation of homeplace with us for the soundscape. And a lot of these stories are very vulnerable, and very telling of the harsh realities that diasporic, marginalised, non-Western people tend to face when moving through this world and trying to transcend things like borders. And so, those stories, demonstrate the social forms of resistance people are employing whilst trying to construct homeplace.

At the same time, you'll start to hear hints within that soundscape. What do people arrive to? How do people construct community? The people we invited come from very different walks of life, and we found that to be very important in a place like the Pinakothek, where there are thousands of people moving through the space. We were also thinking about the people who spend the most time at the Pinakothek: the people at reception, and security guards who tend to follow that kind of life that includes unhoming. The sound serves as an invitation to learn across cultural differences.

The question was, what are the kinds of responses and forms of comfort and solidarity that can be formulated through listening to others?

Black matters are spatial matters. And while we all produce, know, and negotiate space, albeit on different terms—geographies in the diaspora are accentuated by racist paradigms of the past and their ongoing hierarchical patterns. – Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (2006)

Mrinmayee: Spatialising the idea of fellowship and community among marginalised and/or diasporic communities, and creating an experience of it is quite a poignant accomplishment. One last question: I wanted to know if you have received any feedback from the people who have visited the space. How have they reacted to your intervention?

Khensani: I have to share a story with you before answering your question entirely. We noticed something the first time we were invited by the director of the Architekturmuseum der TUM. On the first floor, you could see a nice view of the rotunda. Through the nook, a group of little kids entered with their caretaker or teacher, and they sat down around the installation that was on display. There must have been 15 of them, and they formed a circle to rest. It was an important moment for us to witness because, in many of our cultures across the African continent, we have this practice which I will refer to as imbizo, though it has many different words to refer to it.

An imbizo means to gather. It also has an explicitly spatial form: it is always round and happens in the open space. Within the gathering, everybody has the right to speak, but also to listen. When we saw the kids, we were all thinking, “Hey, here is a group of children in Munich who are doing imbizo. So, why don't we try to find points of connection across cultural differences rather than emphasising those differences as a form of divide.” I think a lot of the responses to the space have been in line with that thought and the dialogue that we have been trying to create.

We had an incredible vernissage where a lot of people from the local community came. A lot of them were touched particularly by the soundscape, because one force of unhoming is isolation, not recognising that others are also going through the forms of terror that socio-political forces impose on people who are not allowed or by default part of that land. So, the responses from people within the diasporic community were a sense of gratitude and a sense of relief. Many intersectional families also found that to be a beautiful point of connection because they could learn and create a dialogue within their homeplaces because of the kind of prompt that this artwork served us.

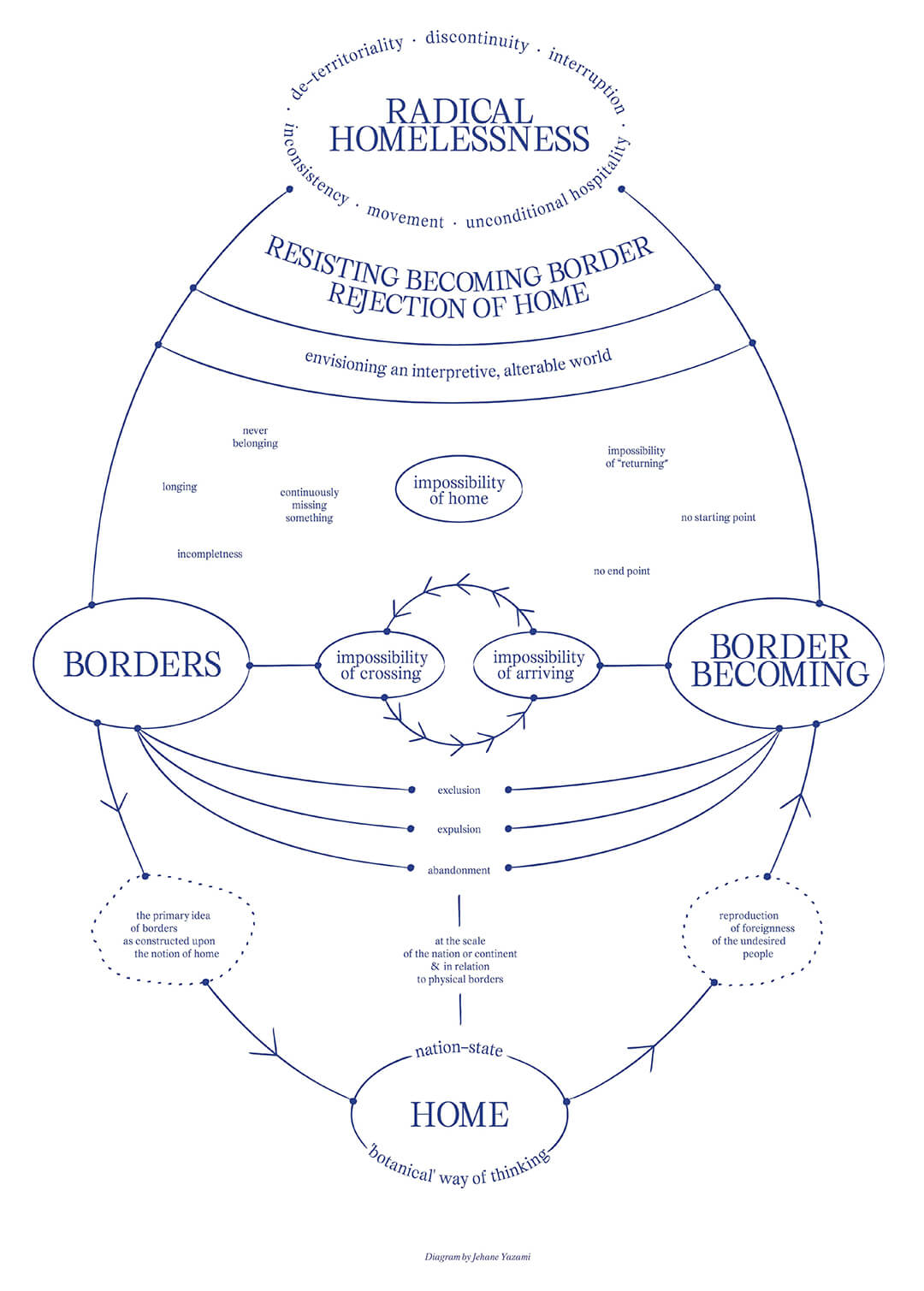

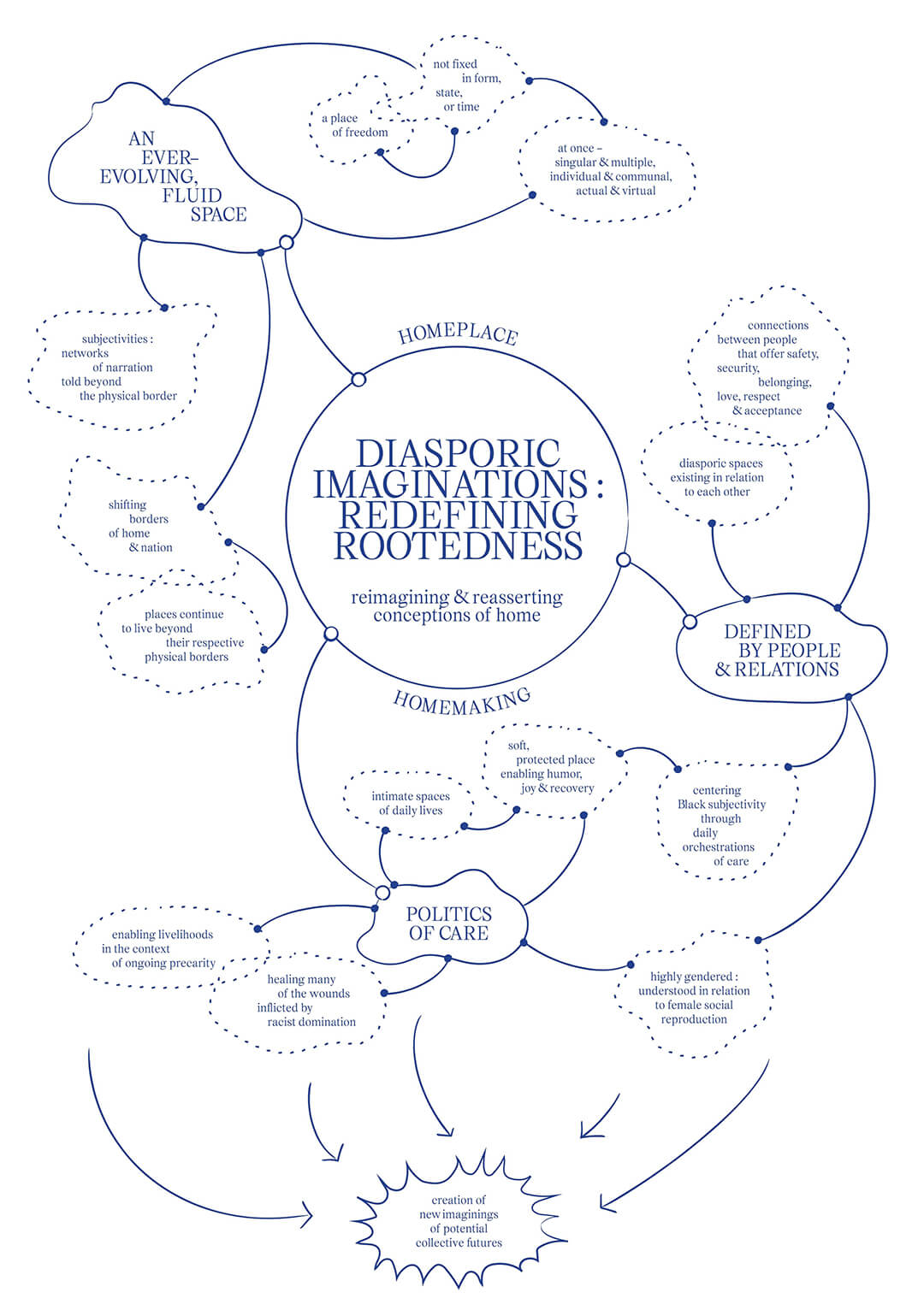

Selected quotes and diagrams have been taken from the catalogue accompanying the installation to add a multiplicity of voices that elevate diasporic imaginations of home, as a means to understand our past, but also to situate ourselves better in the imagination of our future.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Feb 29, 2024

What do you think?