Exploring Washington through 'Capital Brutalism' at the National Building Museum

by Dhwani ShanghviNov 11, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Alisha LadPublished on : Dec 13, 2024

With its unapologetic material honesty and utilitarian ethos, Brutalist architecture has always evoked polarised reactions to the built environment it inhabits. To some, it represents an era of social idealism in architecture, while to others, an architectural overreach. But its quasi-revival over the last couple of decades in regions and nations that had since moved away from its puritan ills—a reinterpretation labelled (often inaccurately) as a ‘Neo’ Brutalism—marks more than a mere stylistic return. It stands as an ideological evolution and a call to action against material waste, ecological insensitivity and architectural disconnection.

It would then seem like the closest one could come to recontextualising Brutalism with these tenets (and in the face of a looming climate crisis) would be through lending this twist to facets like natural age and decay in existing structures, wherein a language of truth, of brutality, is borrowed rather than created. The German architecture and design firm b+ based in Berlin, whose adaptive reuse projects and philosophies exemplify a profound commitment to "systemic thinking, ecological viability and collective responsibility", mirrors this ethos with a certain pedagogic radicality, complementing the Neo- prefix. Originally founded by Arno Brandlhuber and called Brandlhuber+, the firm has since transformed into the collaborative design practice b+, operating in a different constellation from 2022 under partners Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Jonas Janke and Roberta Jurcic. The four partners echo the somewhat revivalist sentiment around Brutalism with an understanding that similarly transcends the aesthetic, attempting to redefine it for a world confronting severe ecological, economic and social crises through operating by penchant at the intersection of theory and practice.

"When it comes to the more common interpretation of brutalism—buildings characterised by concrete, strict geometries and large-scale forms—it’s important to differentiate b+ from this conventional view," the designers caution. The aesthetic of Brutalism owes much to a very particular material palette, but the ‘brut’ in Brutalism once stood as a reference not to a specific materiality but to the raw and unfiltered essence of the material itself. It is in this sense that the work of b+ aligns with the original commandments of Brutalism, where an emphasis on unrefined material honesty transcends today’s (brutalist) stereotype of stark concrete and monolithic forms. For b+, who aim to champion circular design, concrete is pragmatic and does not hold an aesthetic reverence any more than brick architecture. “When considering adaptive reuse, the term ‘as found’ might be a better starting point,” the designers reveal when asked about materiality.

When considering adaptive reuse, the term ‘as found’ might be a better starting point.

In its enhanced visual sense, Brutalism is especially resurfacing and making its place in popular culture, often through a nostalgic lens or one of aesthetic fetishisation and b+ remains cautiously optimistic. While the growing media fixation risks turning the pathos around brutalist architecture into ‘just another fashionable trend’, it has also helped normalise what has long been and still is, considered ‘ugly’ architecture by social standards at large. This has often led to the idea of doing away with the ‘ugly’, demolishing it and circumventing adaptive reuse entirely. However, even as we embrace raw architectural imagery, it is important to discern whether making it trendy contributes to more waste. “This creates an interesting conflict, where architects have a responsibility not only to engage with the aesthetic but also to raise awareness of the broader implications,” b+ points out, reminiscing about their first retail project. Despite having a client swayed by the fetishisation of raw concrete and ‘brutalist’ aesthetics, b+ broke down the true meaning of brutalism as they understood it, creating a fully circular space. “All furniture and building parts could be unscrewed and reused and even the walls were covered with clay instead of concrete,” they explain. This critique is central to their practice, which resists superficial interpretations of the style in favour of its deeper principles: material honesty, structural clarity and ecological sustainability.

We are slowly moving into a time where reusing the existing is becoming the new norm and no longer considered too risky, unknown, or unpredictable.

The rawness of concrete isn’t merely visual; it is structural, historical and mutable—with robustness and adaptability suited for transformation—it is ultimately the relationship the original architect shares with the material in question that b+ turns to. “We see significant reuse potential in concrete structures, but that being said, the most flexible type of existing building might actually be a brick construction,” the architects note, as illustrated in one of their most celebrated projects to date: ‘the Antivilla’. Here, they could puncture holes and accommodate openings even in the external walls, lending a freedom of transformation that is not easily afforded.

This is also where b+ sets itself apart, delving into a world of theory and abstracting these lessons. “Stepping back to look at this issue from a systemic level, we realise that the material question becomes a question of time. Which materials do we use and for what purposes, to open possibilities for the future?” they question. When discussing 'good architecture’, Bob Van Reeth—elected as the first “Vlaams Bouwmeester” (Flemish Government Architect)—reminds us of the importance of designing buildings for an unknown future. In doing so, he coined the concept of ‘intelligent ruins’, which ultimately even provided the building blocks for Belgium’s successful public architecture, now being globally acknowledged as an ugly-turned-genius buildscape.

When a ruin’s spatial complexity still evokes a functional promise, a ‘yet-to-be-imagined’ use; architecture and design change. b+ gives us an example: we continue to hide technical infrastructure in central shafts in a building, despite knowing they will need replacements due to shorter lifespans. In an ‘intelligent ruin’, these would migrate to the exterior, making them visible on the facade for easier, faster and cheaper replacement. Although for cost and aesthetics, we continue to conceal them, preferring to demolish, redesign and rebuild rather than build for an uncertain future.

One thinks of architecture within limited frameworks (form follows function and conversely, function follows form, form follows feeling and so on) but when dealing with existing buildings, only one challenge becomes apparent: to prove reuse potential through design to serve economic feasibility. The designers turn to San Gimignano Lichtenberg as an example, which involved the reuse of two concrete towers (remnants of a former GDR factory for coal and graphite) which fell into ruin after the fall of the wall. It was soon privatised and became a Vietnamese wholesale market dominated by one-storey warehouses. Here, redevelopment seemed senseless and demolition costs were too high, allowing a window in which b+ could step in and rewrite a narrative of obsolescence. Over 10 years, they worked to shift perceptions of the towers, once symbols of ruins, into a vibrant prototype, drawing parallels to the Tuscan village of San Gimignano (famous for its massive towers) and renaming the project. “Today, the transformed silo tower stands as a built argument, highlighting the many obsolete, unused typologies in our cities and offering an inspiring example that adaptive reuse can be a viable alternative to the conventional mindset of ‘demolish and rebuild’, the team elaborates.

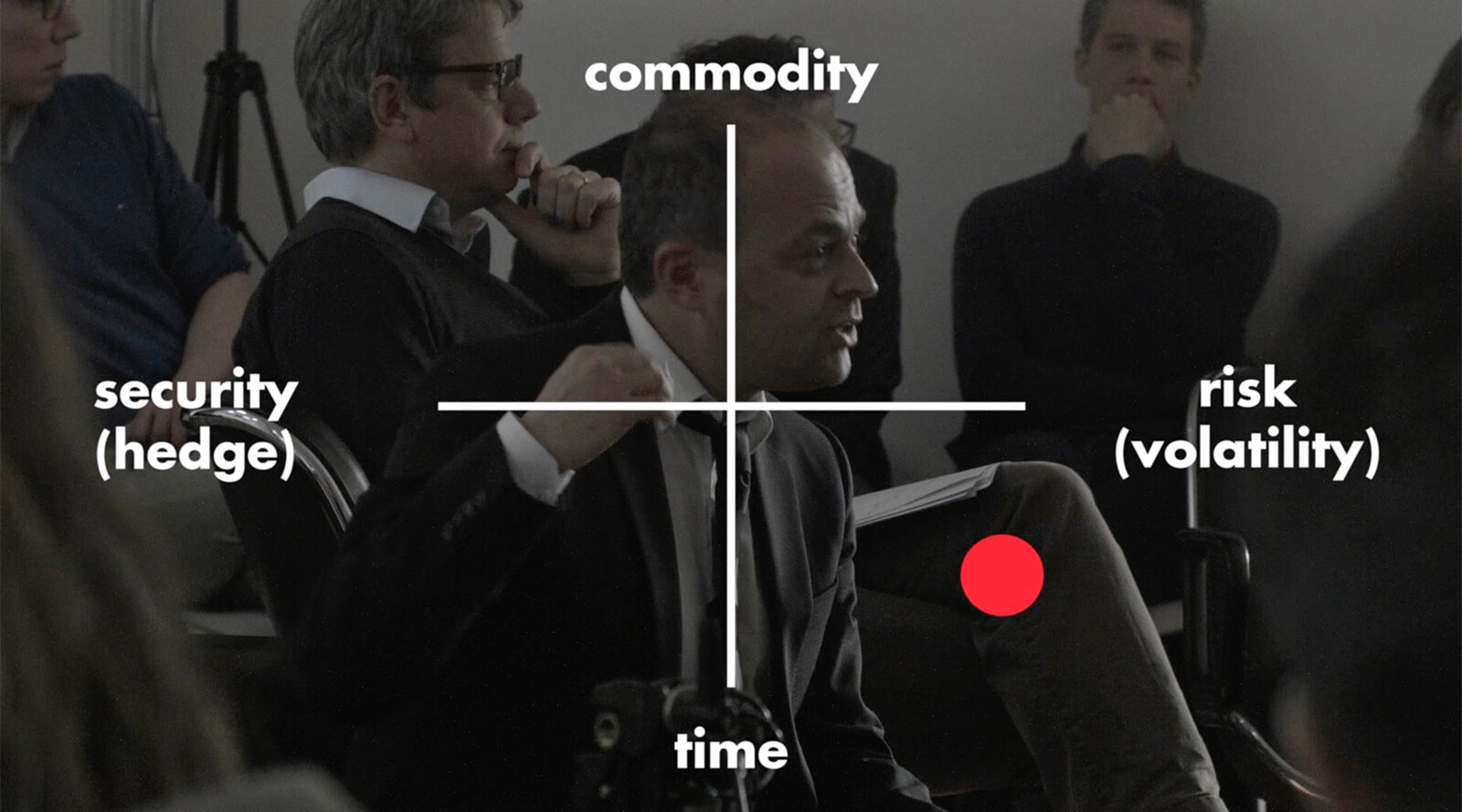

Berlin, with its unique post-reunification landscape, has been fertile ground for b+’s adaptive reuse projects. The city’s economic conditions—a surplus of unused spaces coupled with a tolerance for risk—allowed experiments like San Gimignano Lichtenberg to flourish. However, as reuse becomes a global necessity, b+’s philosophy transcends geography and edges towards a larger issue: what do we, as ‘consumers’ of architecture, want to spend our money on, material or labour? With decades of working towards a clear goal of maximising profits and reducing costs, the building industry and by extension, adaptive reuse, becomes political, shifting economic value chains from material to labour.

Their recent adaptive reuse – in collaboration with Snow Kreilich Architects – of a former limousine garage in Minneapolis into an art centre named the Midway Contemporary Art serves as a strong example of using the redesign process to unlearn and rethink the construction sector’s current approach. In the case of repurposing this two-storey warehouse, b+ followed a phased approach, balancing ecological responsibility with community engagement. Typically, the solution would have been to demolish and rebuild, but in this unique case, it only took the removal of a few prefabricated ceiling elements, steel to reinforce walls and wood for new interior separations to transform the building, freeing up resources for the second phase and underscoring b+’s commitment to long-term, systemic impact. “Social intention is important and we want to help shift markets towards labour and recognise the potential for small, local businesses and architecture firms within the renovation and transformation sector,” b+ says.

So what does creating a new value system in architecture look like? b+ defines three principles for this change (collective responsibility, systemic thinking and ecological viability), exemplified by their flagship initiative, ‘HouseEurope!’. Beyond being a design project, it is a manifesto for systemic change, a movement that urges architects to embrace activism and to make renovation the norm. By proposing legislation that prioritises renovation over demolition, it seeks to normalise adaptive reuse as an ecological imperative, recognising architecture as both a political and cultural act. “The demolition of existing buildings is as outdated as food waste, animal testing or single-use plastics,” the firm asserts, especially in our times of climate change, resource limitation and material scarcity when the act of erasure only highlights broader ecological irresponsibility. The firm’s architectural expertise meets storytelling methodologies developed at ETH Zurich’s Station.plus (s+), to craft compelling narratives that rethink the advent of an architectural object into culture.

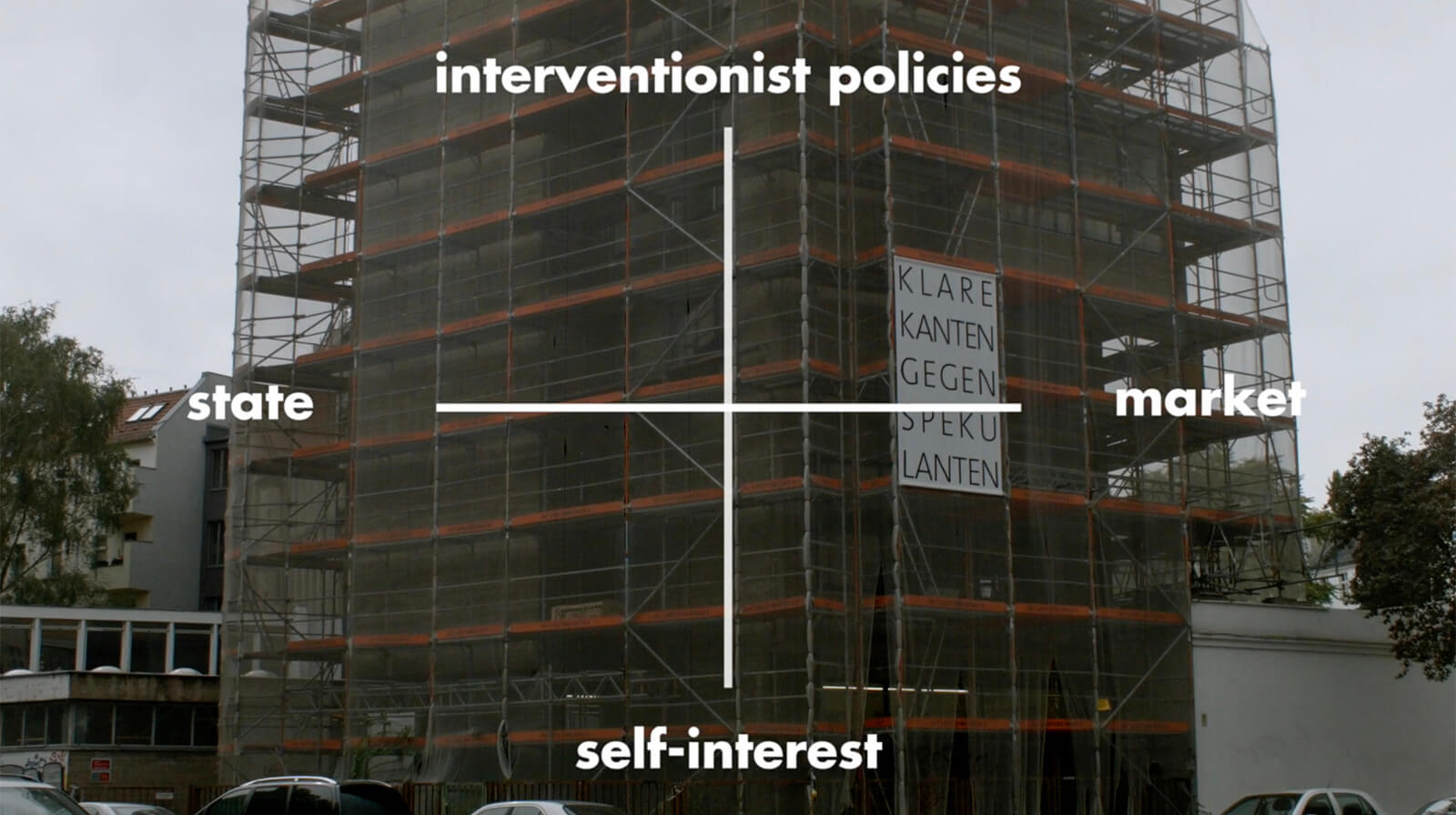

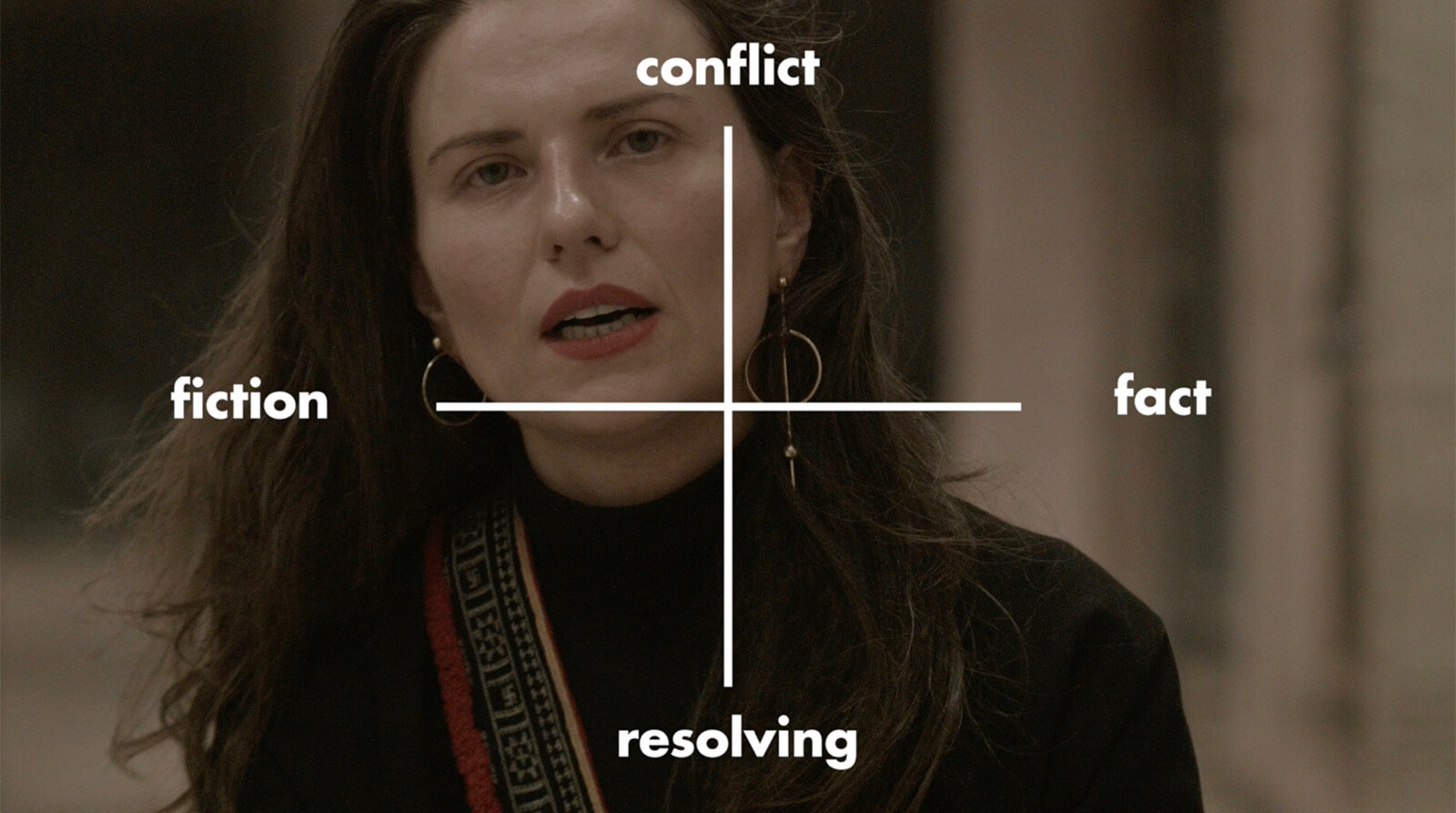

This philosophy was amplified in ‘2038 – The New Serenity’, their speculative project for the German Pavilion at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Using narrative-driven speculation, b+ invited audiences to envision a world where systemic changes have already been implemented. The question they pose is simple yet profound: What future are we designing for and at what cost? “Many conflicts today cannot be solved on a micro-scale,” they argue, positioning themselves as architects of systems rather than objects. This is further evident in their Legislating Architecture film series, where they explore architecture as a verb (architecting)—a process of negotiation, storytelling and speculation.

Their collaboration with Christopher Roth, particularly the film Architecting After Politics, reframes architecture as a collective act extending beyond buildings, incorporating global and local dynamics and questioning binaries like public vs. private and fiction vs. reality. This intellectual rigour challenges not just architects but society at large to reconsider the frameworks that define our built environments.

For b+, the HouseEurope! initiative, which aims to collect one million signatures for EU-wide legislation on renovation, reflects their belief in collective action and highlights the social and cultural stakes of their work. “Every building we save is a story preserved,” they assert. The firm’s commitment to reform the complex conditions that create the framework in which architects operate through material innovation and narrative-driven design positions them as bona fide torchbearers of Neo-Brutalism. In their hands, the rawness of Brutalism isn’t just an aesthetic but a philosophy that bridges the past and future, challenging us to build not just for the now but for the generations to come. Beyond architecture, b+ approaches adaptive reuse with a lens of shifting paradigms – economic, social and cultural. By redirecting value from materials to labour, their projects bolster local industries, preserve memories and create sustainable systems. As they share, “Architecture isn’t just about building—it’s about imagining and advocating for futures we haven’t seen yet.”

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Alisha Lad | Published on : Dec 13, 2024

What do you think?