Books on architecture and design coordinating discourse and knowledge

by Jincy IypeDec 12, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Nov 24, 2023

What do Apple, Deleuze, Johannes Gutenberg, Citroen DS, the Bauhaus, Joseph Priestly, and Zaha Hadid have in common? Seemingly unlikely, each of these has played its part in the proliferation of digital culture as we know it today. Weaving together anecdotes from history, art, architecture and design, Stephen Eskilson’s new book, Digital Design: A History explores how what we term digital design developed right from the onset of the electronic age in the 1950s.

Drawing parallels to the nineteenth century, Eskilson argues that the experience of the digital is something that has always been, and in a way will continue to be inspired by the analogue. This is in contrast to most savants of the “digital revolution”, who have viewed any progress in digital technology as a new frontier. This topic warrants attention, especially in light of the emergence of AI technology which has been projected to change how computers interact with us. To note, Eskilson hesitates from defining what digital design is, writing “The term ‘digital’ originated with the Latin word digitus, which means fingers or toes—appendages that are the analogue gateway into counting.” He continues, “Today, digital design is still an emerging concept; it connotes a slippery discourse, continually contested and evolving. In its narrowest sense, ‘digital design’ is often used as a synonym for ‘screen-based graphic design’. While this type of digital design rightfully has a high profile, it is by no means the totality of the field.”

As computers have come to mediate even the most mundane aspects of daily life, many people have further expanded the term to define human experience in the broadest terms: a digital age – Stephen Eskilson

The book goes into one aspect of the elastic history of the term and explores how human-machine interaction has evolved by looking at the tangible aspects of the culture. Eskilson probes into the interaction between people and technology—how this is mediated by designers—and the reactions to such. His central argument is to dispel the notion that most designers in the ‘revolutionary’ realm of the digital hold: that what they are doing is futuristic and untethered by the past when in fact it is rooted firmly in it. The book presciently reveals our relationship to something we don’t really think too much about, the nebulous, undefinable cloud called the digital, and data. This becomes a crucial addition to the discourse when most of our lives are online and will continue to become more so if platforms such as the Metaverse are to be believed. The author uses the examples of various designers, art pieces, product design and graphic design to paint this rich history, providing a multifaceted account of something that touches all aspects of our lives.

The most tangible aspects of digital culture are those we can see in front of us: the machines we use, the interface and its aesthetic, the parametric styles that advancement in digital technology has enabled and the virtual realms we inhabit and the data they represent. The book can be neatly divided into these themes. It starts with the development of the machine, what made the digital possible; moving on to the look, what made the digital personable; to the data: what really is the digital.

Before the personal computer, the internet, or even virtual reality came the visionaries. The science fiction saints believed a better world was possible and the digital revolution would facilitate it. They sought to project what digital design was doing, could do, and would do. Perhaps the most recognisable name, the patron saint of the digital age and its language, was Marshall McLuhan, who wrote Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man which would garner attention after the advent of the internet. Talking about how electronic media would revolutionise communication technology, his was a vision of incessant optimism. While the visionaries believed computers would lead to a more connected world, they could only do so through the right technology.

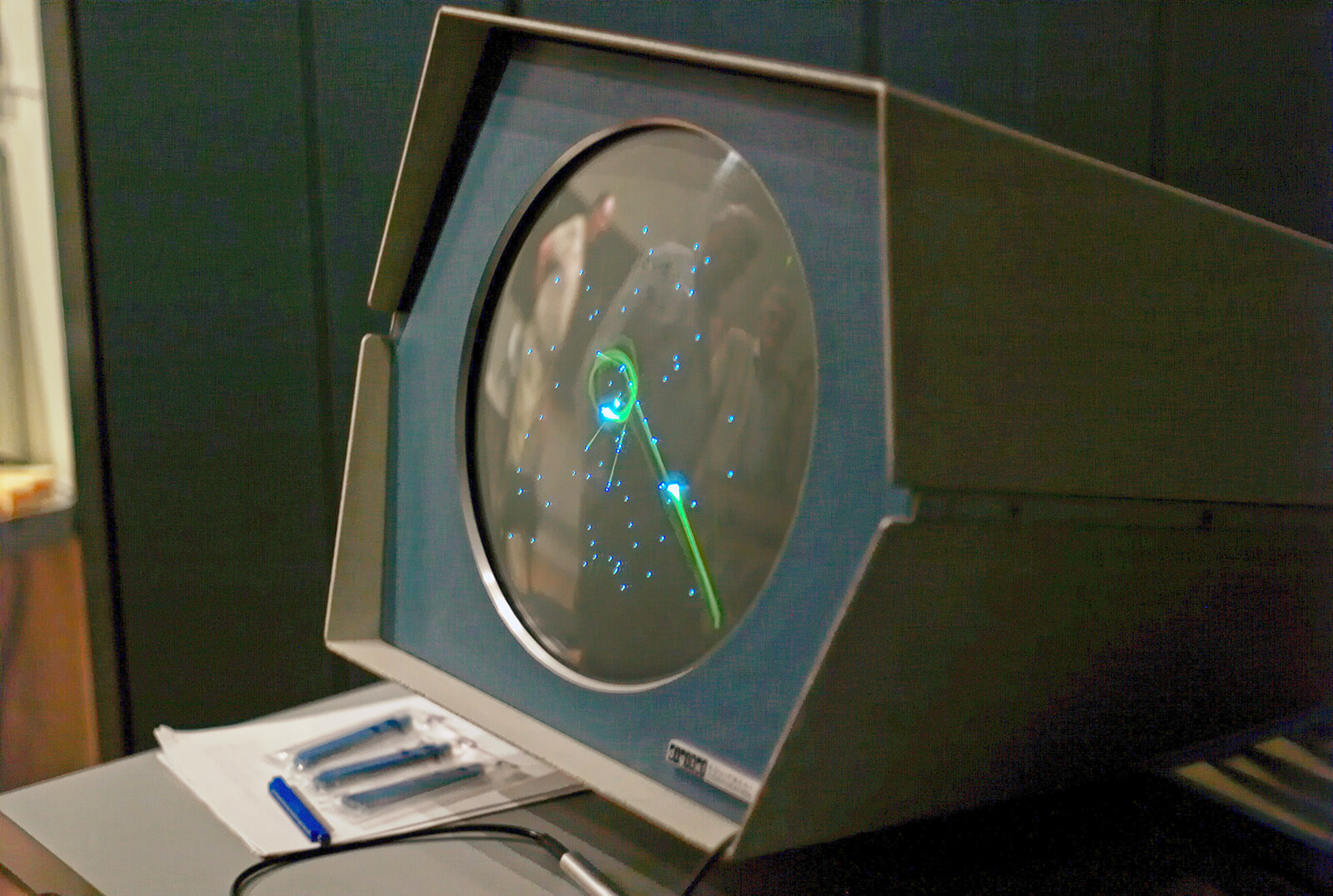

In the second chapter, the book delves into the history of creating this right machine and its precedents. It delves into the contributions of IBM, XEROX and MIT Media Labs in the development of the user interface and dissemination of computers into popular culture, which has shaped people’s ability to interact with evolving technology. The chapter begins with how curvilinear design, such as that of the Citroën DS car, led to innovation in drawing software and, subsequently, the graphic user interface. From a combination of analogue craft and digital mapping to creating software that could create digitally has been a long journey as put forth in the book. Without diving into it, he shows how the modern computer system evolved from the contributions of designers such as Eliot Noyes, who brought with them a Bauhaus sensibility to product design (ref: page 29). This aesthetic was employed to increase functionality and relatability with the technology but looked nothing like the visions of science fiction. Tracing the history of Apple and its GUI (Graphic User Interface), he also highlights the importance of skeuomorphic design in establishing a connection to humans. He further explores the idea of typefaces and how they inadvertently determine the relationship between man and machine in the third chapter.

When talking about innovation in computers, one can hardly skip mentioning the pivotal role of video games and experimental film. Since much of digital design has sought to create immersive, interactive experiences that are joyfully engaging. The chapter freewheels from the work of digital artists such as Oskar Fischinger whose work provided precursors to the introduction of colour to digital to the work of lighting designers such as Glenn McKay. Video games have been vital in the enhancements to machine interfaces. A designer he includes is worth mentioning for his egalitarian vision. Chris Crawford’s 1984 book, The Art of Computer Game Design, showcases his belief that games were best situated to maximise the potential of the computer, fostering more meaningful HCI, which was the ultimate goal of designing GUIs.

Finally, Chapter 9 deals with hard shiny plastic, and traces how the sleek, minimal, technological aesthetic of our gadgets is rooted in the past. Going back to the Bauhaus, he illustrates how designers associated with the movement employed their philosophy of “less is more” to create “desirable” machines. He draws a convincing line from the likes of Jonny Ives to Yves Béhar, lamenting the blending of what could have been surreal looking. As he illustrates, from the invention of portable computers to the digitisation of our homes (a still fluid field), design has always revolved around friendliness and approachability in human-computer interaction. A lot of this can also be attributed to the analogue aesthetic the digital age ended up adopting.

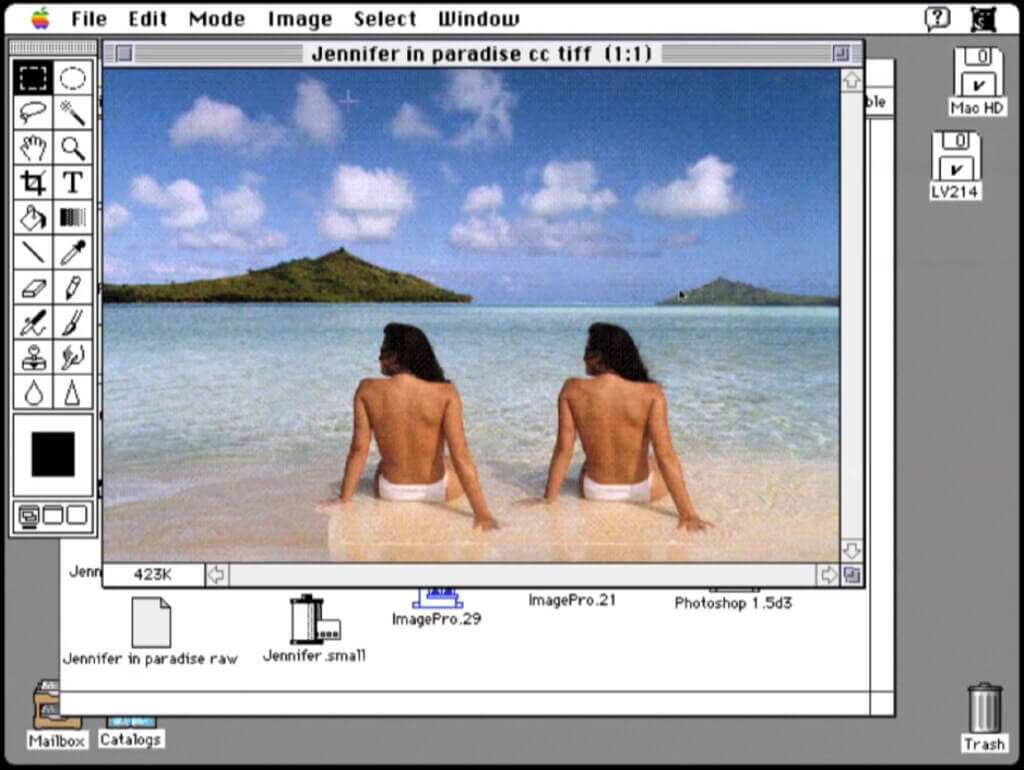

One of the biggest fields digital design helped to advance was graphic design, as Eskilson elucidates. While the onset of affordable printing made graphic design more accessible, Adobe’s release of programs such as Illustrator and Photoshop would only accelerate demand. It’s interesting to note how much the launch of Photoshop would change the realm forever, making the virtual a world of unattainable ‘photoshopped’ beauty. Perhaps the advent of AI and its glossy imagery will be the next chapter in this homogeneous landscape.

In Chapter 3, going back to the influence of type, he shows how the development of the digital aesthetic, which aimed to turn away from the formulaic and staid (such as in the work of Licko), ended up with an analogue-inspired humanist style. This owes a debt to the functional aspirations of the Bauhaus. It is, however, interesting to note that even though digital tools only aid in the creation of tangible objects for architecture and product design, they have pushed graphic design to the virtual.

This is exemplified by the advent of the internet and web design. In Chapter 5, Eskilson details how designers began to navigate the novel space of the World Wide Web, which looked more like a print page at the time of its inception (thus drawing a comparison to Gutenberg). Tracing the history of web design, he highlights the work of important visionaries such as David Siegel, who wrote Creating Killer Web Sites, taking inspiration from Jan Tschichold’s The Form of the Book: Essays on the Morality of Good Design, a decidedly analogue reference. He elaborates on the rise and fall of Flash-enabled websites in Chapter 7, highlighting how art and experimental play again performed a central role in shifting the focus of the design community.

Perhaps the most incongruous Chapters are 6 and 8, where he talks about the development of a digital aesthetic for architecture. Starting with the Sydney Opera House by Jørn Utzon and Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by Frank Gehry, he shows how digital design has revamped the approach to architecture and its production. He defines certain moments through the theories of Peter Eisenmann and Greg Lynn, noting their affinity to Deleuze and post-structuralist theory.

While he demonstrates how digital technology aided architecture and changed how designers worked, it’s hard to look past the fact that he only delves into the form of architecture, touching upon the process of production but does not mention the utopian visions of those such as Archigram whose work explored how computers will change how we deal with the built environment. In the other chapter on architecture, he talks about the rise of parametricism, the new architectural style after modernism, according to one of its pioneers Patrik Schumacher, Principal of Zaha Hadid Architects. Schumacher, who has now been prolific in his support for virtual architecture argues that parametric architecture is the only style capable of expressing the complexity of contemporary society. Eskilson rightly points out that digital technology, parametrics, AI and the like will lead to more customisation, prefabrication and 3D printing in the production of architecture leading to advancement but not an outright insurgence.

We live in a tech-mediated world. And in this world, it is hard to escape the mundane reality of data and how much it has come to define our age. In Chapter 10, the discussion thus shifts to data: its forms, representations, and organising principles. The chapter looks at artificial intelligence, dismantling the common notion of HAL-like sentient beings. Instead, as he shows, what is marketed as AI today is actually algorithmic design.

Algorithms really came into their own with the arrival of the digital age, with computers today having the capability of almost instantaneously implementing myriad algorithms on a vast amount of data, in a way emulating the intelligence of a sentient machine.

Many design projects that use algorithms, marketing them as AI are mentioned by the author to debunk the idea of the pervasiveness of AI in our daily lives. He uses myriad examples to illustrate his central thesis of making technology more human, from musicians to product designers. Further, taking a positive stance on algorithms, he uses cases to show how it might help us design better. For instance, he brings up how Nike has taken to using algorithms to make size-specific alterations to its sneakers, which means saving on materials and cost.

Using multiple examples, he shows just how ordinary algorithms have become in our daily lives. Inconclusively, he writes at the end, “One last point about algorithmic culture: How will future historians make sense of social networks that are ruled by personalised computations? Would it ever be possible to understand the experience of a photostream or newsfeed that is tailored to the individual in real time? Additionally, the simple quantity of posts, memes, and snaps seem likely to bedevil even the most assiduous student of the digital past.”

As he illustrates in the last chapter, the human need to document has a long history. Starting with cartography, he traces how we’ve processed large amounts of data through visualisations. He talks about Joseph Priestley, the pioneer of the now ubiquitous ‘timeline’, William Playfair, and the works of the likes such as John Snow, who created specific maps to understand particular phenomena. As management theorist Peter Drucker notes on the shift to a knowledge-based workforce today, “What we still have to create is the conceptual understanding of information […] We have to have a ‘notation,’ comparable to the one St. Ambrose invented 1,600 years ago to record music, that can express words and thoughts in symbols appropriate to electronic pulses.” The computer was always poised to be that system.

One last point about algorithmic culture: How will future historians make sense of social networks that are ruled by personalised computations? Would it ever be possible to understand the experience of a photostream or newsfeed that is tailored to the individual in real time? Additionally, the simple quantity of posts, memes, and snaps seem likely to bedevil even the most assiduous student of the digital past.

The chapter goes on to name several examples of how design has been instrumental in making the exabytes of data available on the internet intelligible to people. One such example is the No Ceilings project. Funded by the Gates and Clinton Foundations, the initiative focused on fostering global gender equality. In some ways, this has also helped make the almost incomprehensible amount of information the world currently possesses far more relatable. He shows how the idea of interactivity plays a big role in this development.

Going back to the fourth chapter, where Eskilson talks about video games, they have perhaps been the most instrumental in fostering human-computer interactions (HCI). First-person shooters offered a sense of autonomy that mirrored the utopian strain in digital culture, and multiplayer adventure games further underscored the feeling of living in a virtual world, offering interactivity and a sense of connection. A case in point is Philip Rosendale’s Second Life, which was opened to the public in 2003. Based on avatars, Rosendale had hoped for a “hyper-fantastic, artistic, and insane [landscape], full of spaceships and bizarre topographies, but what ended up emerging looked more like Malibu. People were building mansions and Ferraris.” We have seen this pattern over and over, starting from the first Photoshopped image, but perhaps the virtual world looks more like Malibu after all.

Discussions of HCI are thus incomplete without delving into virtual reality and its precedents, which the author does in the last chapter. As he demonstrates, immersive environments did not emerge with digital technology, instead having a richer heritage in movies, video consoles and going further back to linear perspective. The rest of the chapter deals with the hardware one needs to interact with VR and how far society is from having a VR headset in every home (like we do personal computers now). However, he makes a prescient comment when talking about architectural visualisations, “The allure of the digital seems at times to have trumped visions of the actual.” A sense of connection and interactivity, a plastic-coated brand of perfection, sleek Bauhaus aesthetics: all of these have contributed to the look of the digital, that indeed somehow still holds the world in sway, and perhaps always will.

As the book illuminates, the development of technology that mediates the relationship between humans and computers has always had two goals: one, to make technology seem friendly and approachable, and two, to better facilitate what we can do with computers. From using the computer to crunch numbers to drawing curves to the onset of the internet, digital culture has evolved to give us “A little bit of everything all of the time”, as internet comedian Bo Burnham puts it in his song on the pervasive internet culture of the day ‘Welcome to the Internet’. In the song, he also mentions that this was exactly what it was designed to do. A fact that often goes unnoticed as we are subsumed by data in every facet of our lives. The last lines of the book don’t present any solution or even a definitive conclusion to the problem of our increasing dependence on machines. Instead, Eskilson quotes digital artist Zach Blas, writing, “Skip the TED Talk: to find out what’s shaping the future, ask Icosahedron.” Perhaps in the age of the data onslaught, only machines are capable of being able to comprehend what the future holds.

by Asmita Singh Oct 04, 2025

Showcased during the London Design Festival 2025, the UnBroken group show rethought consumption through tenacious, inventive acts of repair and material transformation.

by Gautam Bhatia Oct 03, 2025

Indian architect Gautam Bhatia pens an unsettling premise for his upcoming exhibition, revealing a fractured tangibility where the violence of function meets the beauty of form.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 02, 2025

Gordon & MacPhail reveals the Artistry in Oak decanter design by American architect Jeanne Gang as a spiralling celebration of artistry, craft and care.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 02, 2025

This year’s edition of the annual design exhibition by Copenhagen Design Agency, on view at The Lab, Copenhagen, is curated by Pil Bredahl and explores natural systems and geometry.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Nov 24, 2023

What do you think?