Words, spaces & discourses: a look at the best design and architecture books of 2024

by Jincy IypeDec 20, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Bansari PaghdarPublished on : May 30, 2025

"Fables intentionally expand the imagination of children as they distort time and space as well as logic, scale and proportion. Things we architects sometimes do unintentionally!"

– Edgar Demello, Five Architecture Fables

In an immersive convergence of storytelling and architecture—which itself is often elevated to a medium of storytelling—Five Architectural Fables conveys powerful, thought-provoking themes and valuable lessons through surreal illustrations, mystical creatures and numerous literary and popular culture references packaged in five timely fables, published by Chandigarh-based Altrim Publishers. The author, Edgar Demello, a Bengaluru-based Indian architect and educator in his 70s, draws on decades of professional and personal experiences, mixing them with fantastical elements to create these fables. Introducing aspects of architecture and city planning to children and young adults through a wondrous, heartfelt medium, Demello encourages new perspectives towards nature, animals, people and ultimately, our ever-evolving built environments.

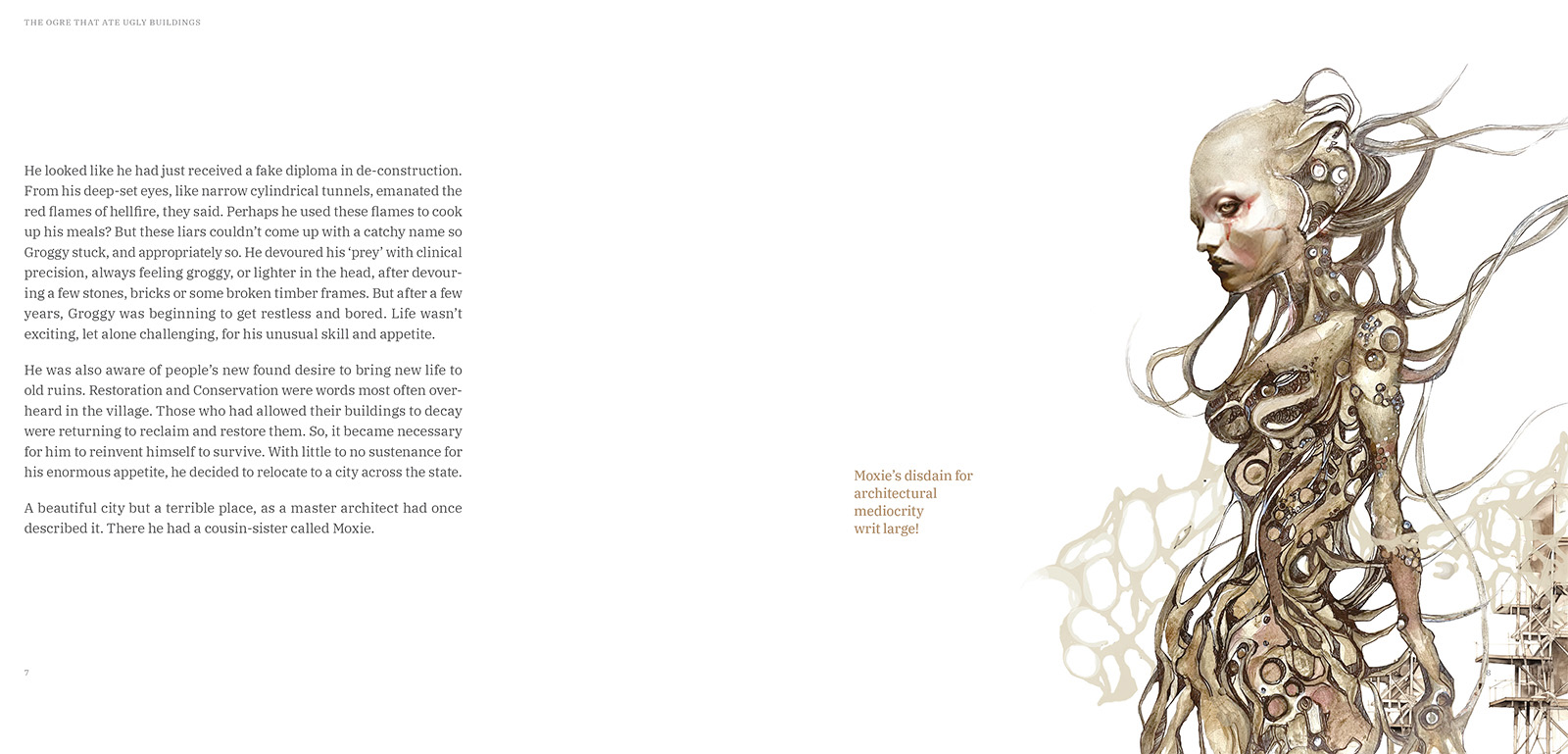

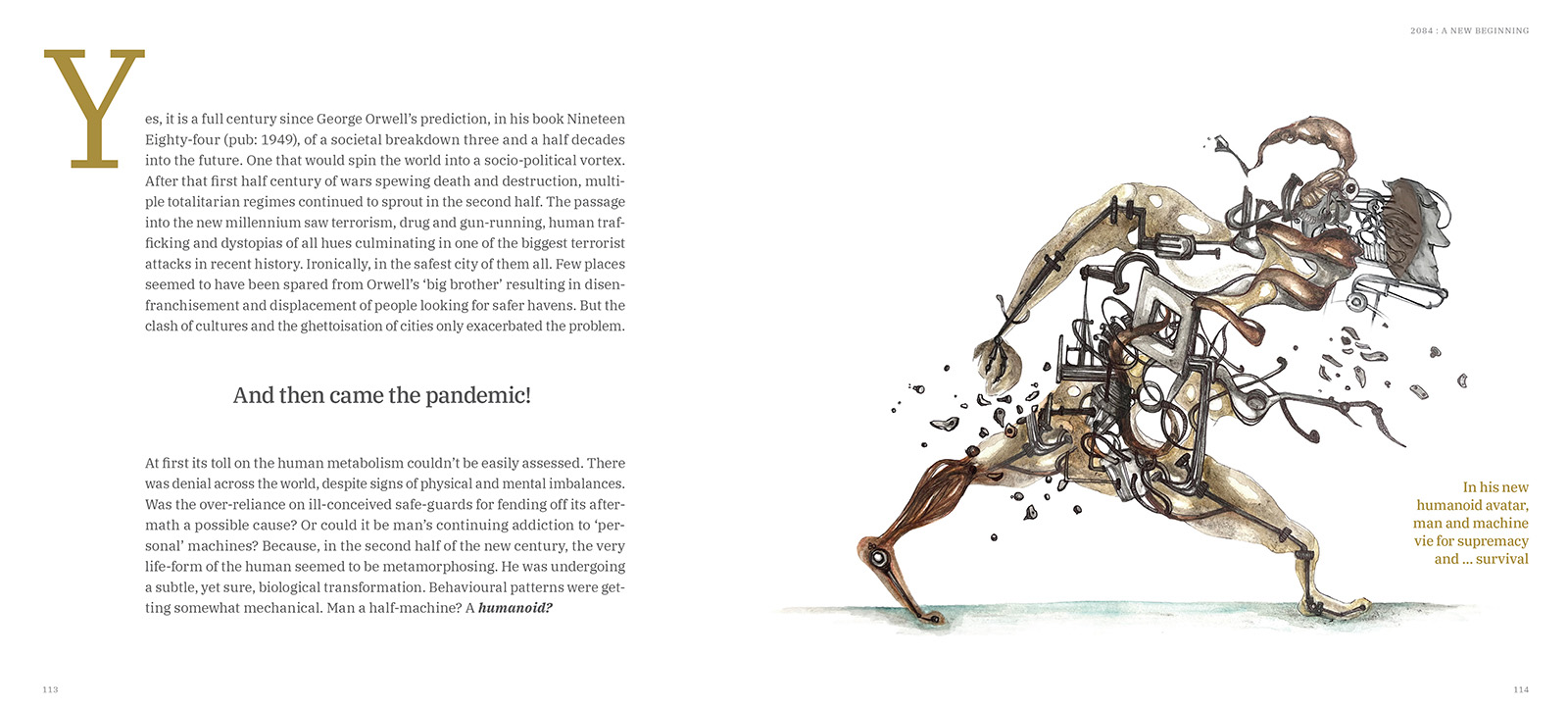

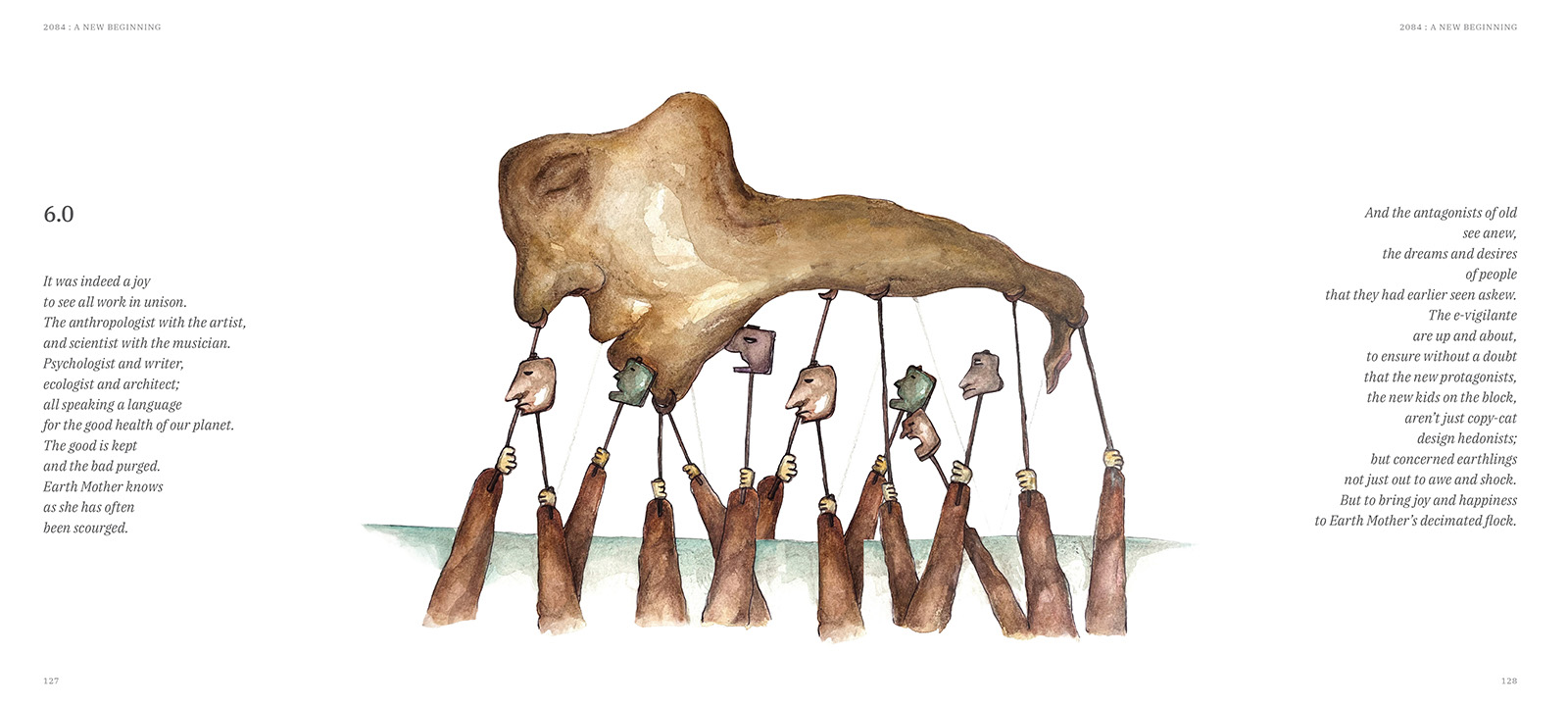

No children’s book is complete without colourful imagery. To that end, Five Architectural Fables features numerous illustrations by Gayatri Ganesh that offer a deeper understanding of the themes of the fables presented. “She captures the core and the flavour of each of the Fables with an imagination and draftsmanship that is truly unique. My favourites are the ones in the fifth fable, the form of the half-man, half-machine humanoid. The angst in the profiles of the intellectuals and the artists is also noteworthy,” Demello states in conversation with STIR, remarking on Gayatri's contributions to the book.

Demello grew up in the coastal communes of Goa, India, listening to the stories of his grandmother, to whom he dedicates this book. Inspiration for the book struck when he came across the 150th anniversary edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—comprising beautiful illustrations by renowned Spanish artist Salvador Dali—and Fausto Gilberti’s tale The Ogre that Ate Children, which informs the first fable in Demello’s book, The Ogre that ate Ugly Buildings. Addressing the themes of (architectural) Practice, Education, Conservation, Building and Future, Demello has woven compelling narratives with simplicity, mirroring the apparent and underlying realities of the profession. Speaking to the shared lived experiences of its readers beyond the architectural fraternity, the book provides strong sociocultural commentary that could potentially resonate with readers from all walks of life. Generating discourse on the state of Indian architecture and several global crises, the book ultimately speculates on the future of the profession, along with the built environment comprising our buildings and cities and by extension, the world.

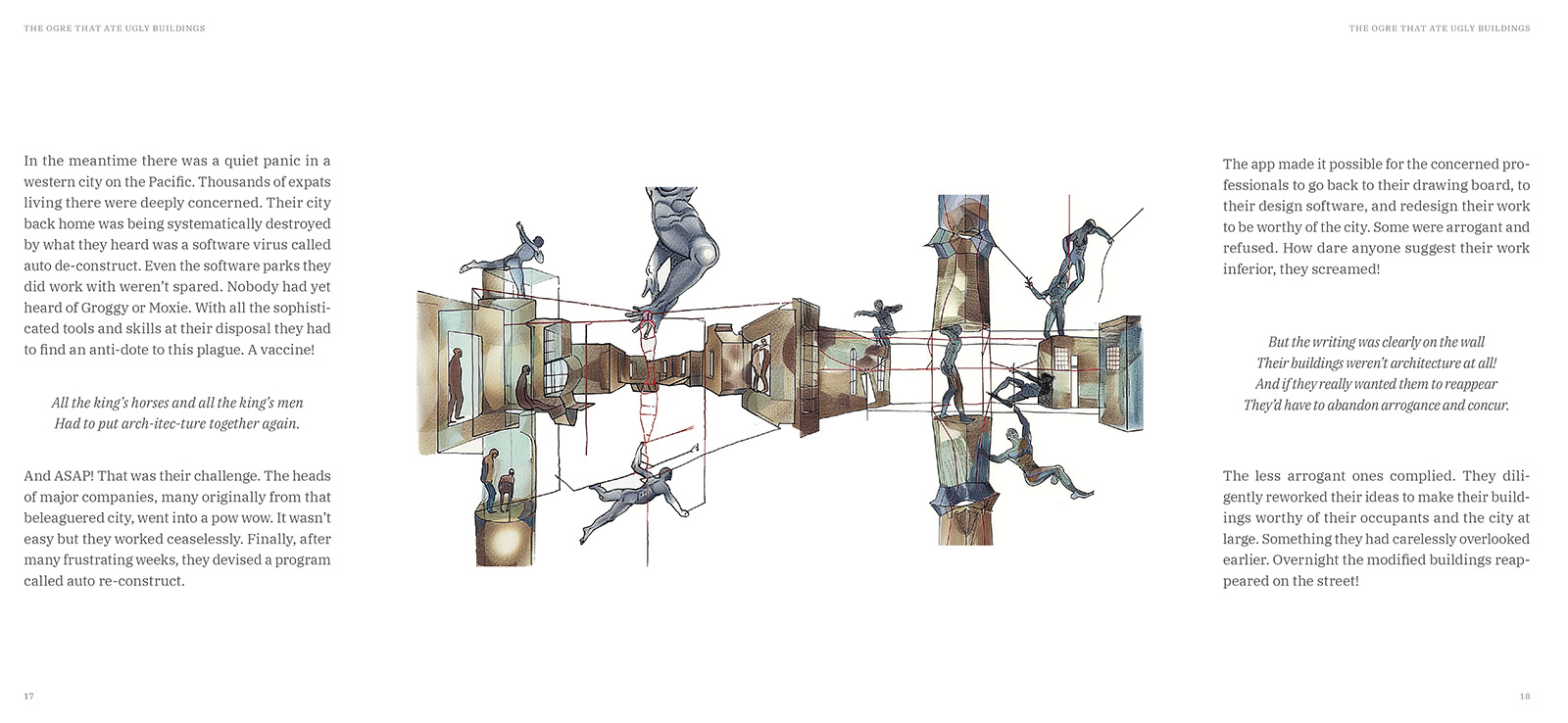

The first fable addresses the themes of architectural practice and follows the story of two ogres that consume “ugly buildings” in the city to make it more liveable, raising several provocations: What makes a building ugly? Can a city, despite being beautiful, be a bad place to live? “We forget that our towns and cities are much more than bricks and stones, they have mythical and metaphysical attributes as well…a city can be beautiful as a physical habitat…and yet fail to deliver that ineffable quality of urbanity that we call: city,” writes Charles Correa in the essay Great City Terrible Place, from his 1989 book The New Landscape—which Demello aptly refers to in the first fable and in his conversation with STIR. One of the drawings in the fable depicts a city as a collection of dilapidated buildings, skyscrapers and poor infrastructure that surround the public, underlining the several socio-cultural issues that lie dormant due to the deafening noise of the unrelenting city and the silence of its suffering populace. Ending the tale on a positive note, Demello orchestrates for the architects and urban planners to go back to their architectural drawings and urban development plans, making their work “worthy of the city”, which leads to the city changing overnight.

That, of course, is a far cry from everyday scenarios that drive Indian cities, where the suffering caused by months of bad planning and years of shoddy construction is measured in lifetimes. The change that Demello foresees won’t happen overnight, nor the reversal of years of damage by malpractice. However, as a start, involved professionals and authorities could let go of their avaricious selves, shed their pride and collectively work towards rewriting the parable of our cities, which isn't far from entirely wishful thinking the way things stand right now. “We Indians do not take critique favourably, which is a great loss for an architect. There is this intellectual deficit, where we are not able to stand our ground and fall apart when someone says something we do not want to hear. We should feel privileged that somebody is providing critique for our work,” Demello tells STIR. Perhaps, self-examination, determination and acceptance are easier to come by when one is willing to learn new things and unlearn the old, remaining a student all their life.

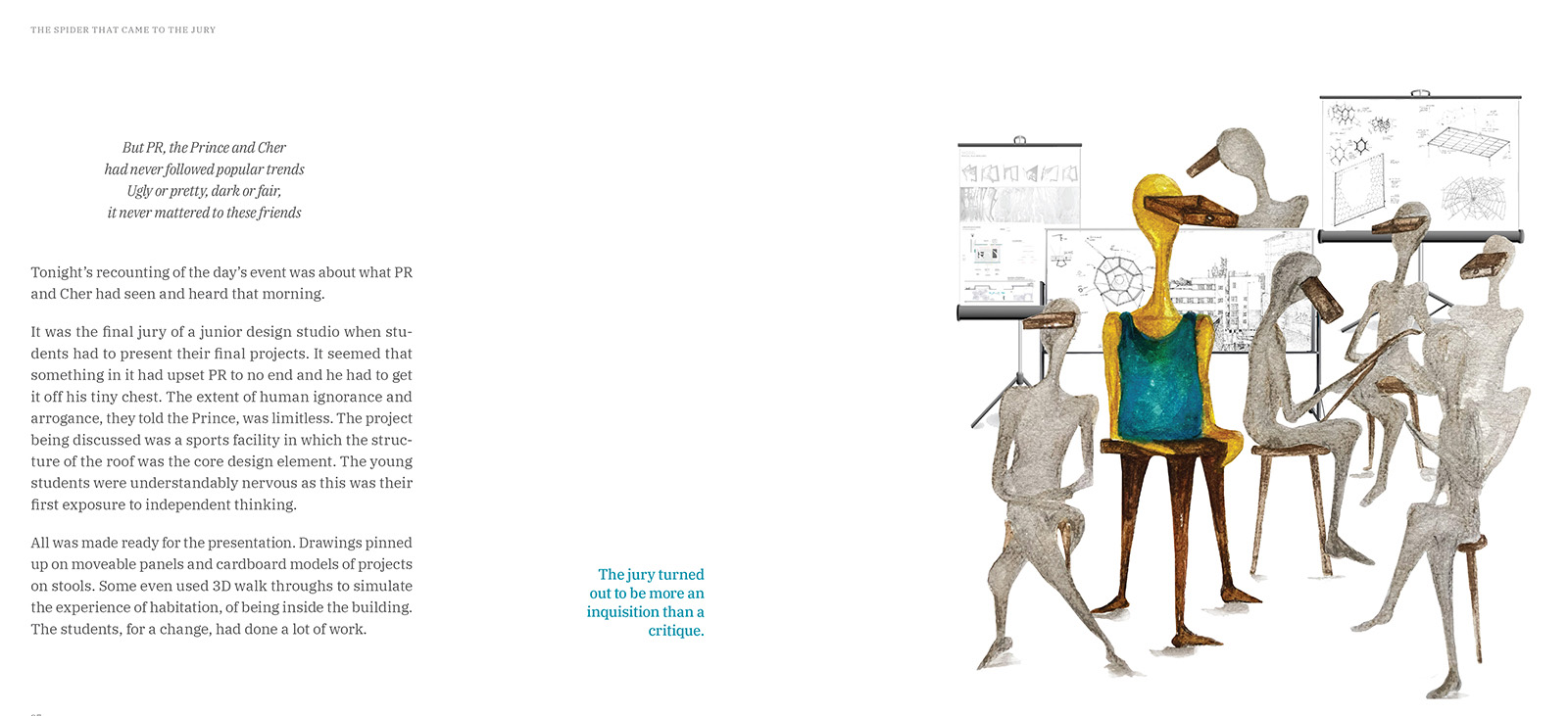

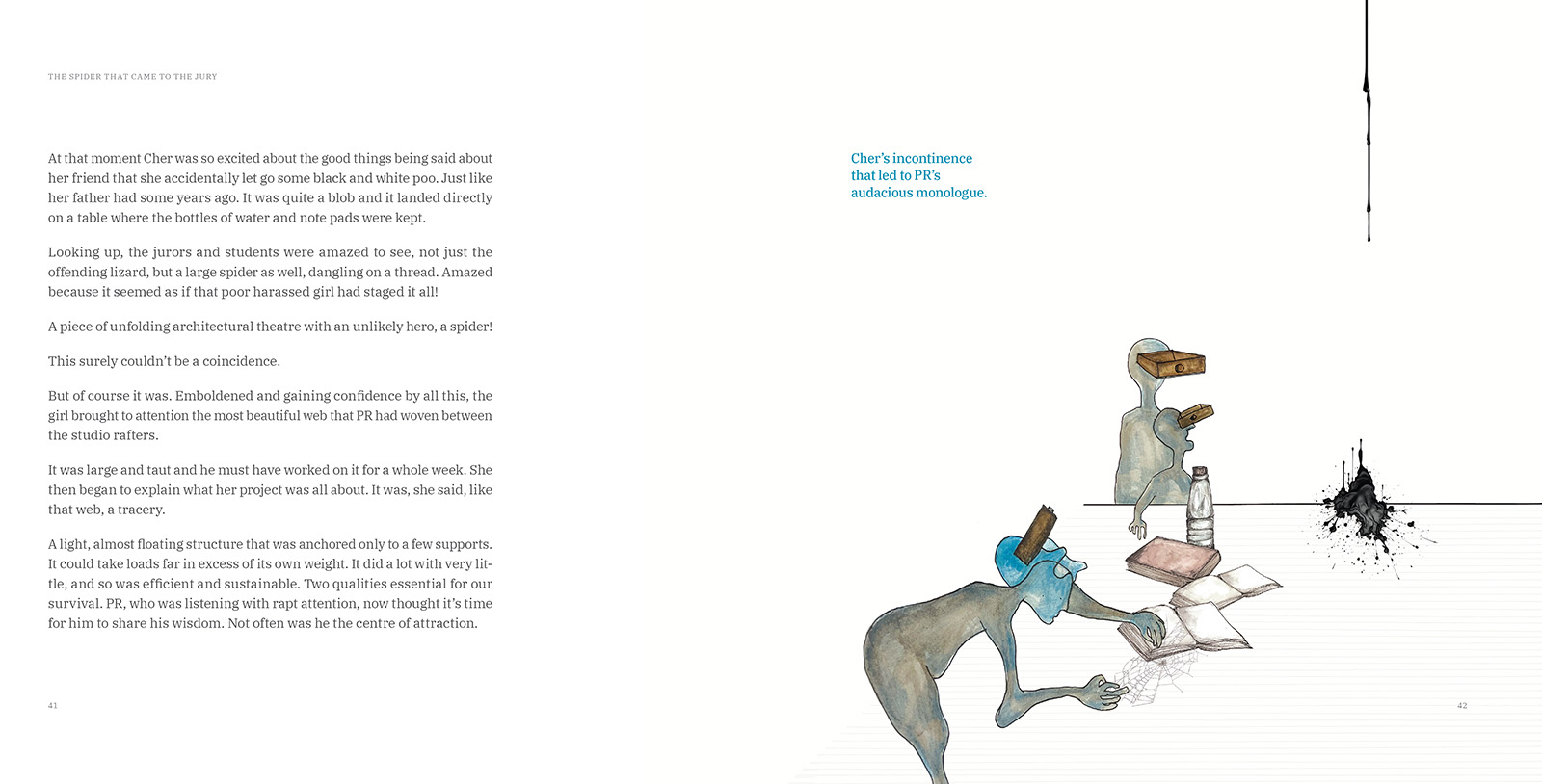

As Demello proceeds to the second fable, The Spider that came to the jury, commenting on architectural education, he is reminded of songwriter Leonard Cohen’s words from his 1966 novel, Beautiful Losers—”How can I begin anything new with all of yesterday in me?” Set in an architecture school, the fable’s protagonists are a spider, a lizard and a bat. The backgrounds of the characters, their characteristics and feelings are conveyed to the readers via several references. While the spider—known for weaving intricate webs—is named ‘PR’ after the renowned engineer Peter Rice, referencing his book The Engineer Imagines, the lizard is named ‘Cher’ after the Dutch graphic artist MC Escher who uses birds, fishes and lizards in tessellations for his artworks, remarked as the ‘Lizard’ of Oz.The bat’s character and origin story, said to have a “Transylvanian mystique” and nicknamed ‘Batman’ of Gotham City, reveals the effects of the global climate crisis and migration. Such references in the fables, along with discussions on themes such as sustainability, biomimicry, recycling and reuse, help connect the readers with the book and instil curiosity for further research, regardless of their backgrounds and age. “The thing about collective lived experiences is that you extract events from your life, taking inspiration from things outside the realm of architecture and other disciplines and give them a surreal dimension,” Demello reveals.

Staging a scene of an architecture studio jury, Demello reflects on teaching methods, portraying a teacher unable to provide valuable critique to a student and breaking their morale instead. “Teachers often impose their learnings and experiences on the students instead of helping them find their own answers,” Demello reaffirms, reflecting on his academic experience. He proceeds to underline the “scary” increase in architectural institutions over the years, commenting on the decline in the quality of education, which the late Christopher Charles Benninger so sharply discussed in his book Great Expectations. “The fables intentionally begin with a critique. We complain so much about the state of Indian architecture, but people seldom write or read about it. There are so many privileged practitioners, some good ones, but most not, because there are simply too many of us,” Demello adds.

For the third fable, The White Owl who saw Red, Demello lays the groundwork for the theme of conservation through Indian author Arundhati Roy’s quote: ”India lives in several centuries at the same time,” from Power Politics (2001), which portrays India as a multitude of temporal realities. Where a rich and complex tapestry of cultures, customs, traditional architecture, rural living and organic towns is juxtaposed with modern lifestyles, technology, contemporary architecture and planned cities. While the characters in the story—an owl, a crow and the head of the local Heritage Watch— struggle to save a tree and an old building, there are other, stronger forces at play to ensure the demolition of these structures, claiming that they have outlived their lifetime. When reverence for centuries-old traditions and beliefs—memories of which are etched in the architecture, towns and cities of India—meets the imperatives of modern development, flawed postcolonial aspirations and global competitiveness, any kind of change is met with resistance. The country’s cultural identity is entwined with its places, which often represent communities, religions, regional identities and ideologies. New development plans often neglect the history and significance of the neighbourhood’s existing architecture, trees and water bodies, along with the temporary markets, lifestyles and memories of its residents. Perhaps, if one embraces the identical complexity and diversity, proposing site-specific, context-driven rural and urban planning under a cohesive, bespoke, hybrid redevelopment continuum, one could begin conserving the past and the future of Indian architecture.

Shared idealism evaporates and greed seeps in. This system, built entirely on ideas, competence and trust, fails when the latter is in deficit mode. – Edgar Demello, Five Architecture Fables

For Two Canines on a Building Site, the fourth fable, designed around the construction phase of an architectural project, Demello takes on the housing crisis of Bengaluru, where groups of young homemakers have been collectively buying lands and employing architects and contractors in an attempt to challenge the system, allowing land prices to rise exponentially as the builders fill their pockets with enormous profits. At the centre of the story is a group of seven friends, along with two intelligent canines who can detect the quality of building materials. One of the friends, driven by greed, attempts to seize control of the project, undermining the architect’s ‘expertise’. The dogs, determined and just, ultimately save the day as Demello concludes the fable with a lesson on loyalty and friendship. Recalling Frank Gehry’s words, “I don’t know why people hire an architect and then tell them what to do,” Demello invites inquiry into how the profession is perceived by non-architects. “Nobody can escape architecture. You have to live in and around it,” he states. Perhaps, it is the fact that lived experience mostly counts for only the finished “products” of architecture rather than a holistic understanding of both practice and product, rendering the impression that design beyond aesthetics is devoid of skill.

Envisioning a world 100 years after George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four , Demello writes the final fable, 2084: A New Beginning, highlighting the collapse of social order as the world falls into chaos. Humankind undergoes metamorphosis, biologically transforming into humanoids with mechanical behaviours, now equipped to fight against an “evil parallel intelligence”, as Demello calls social media and, by extension, AI, in the light of recent AI debacles. What follows is an intense, powerful series of poems portraying humanity’s struggle to overcome ignorance and greed, nearly destroying the world and nature’s healing embrace that ultimately restores balance. A phrase stands out, almost like the dawn after a long night: ‘A Manifesto for Oneness’; quintessentially carrying the essence of the five fables.

Demello reflects on this ‘oneness’ by recalling a discussion with his wife in his conversation with STIR. “Our planet exists in a duality—the earth and the world. The ‘earth’ is what we inherited from our ancestors and everything that we are doing to it comprises the ‘world’. It is all about renewal, ideas and imagination. We (Indians) have always stressed the importance of the ‘collective’ rather than the ‘individual’...we have worked hard to come into our own as a country that has emerged from threads of memory, weaving a vibrant cultural fabric. How can we even think that we can survive without working together as one?” Referencing Bob Dylan’s song All Along the Watchtower—reminding the readers of how the rich, powerful and privileged exploit the outcasts and the less fortunate, and John Lennon’s Imagine, which the author describes as “an immortal ballad for peace”, Demello glances at his peers and the future generations with hope and awaits the dawn of a “new age”.

The fables in Demello’s book strongly portray a sense of optimism and idealism, embodying the inherent feel-good nature of fables that often end on a hopeful note to positively reinforce morals and lessons into children’s psyche. From the outcasts being the heroes to unbreakable bonds of friendship, the tales employ relevant social themes to evoke empathy and personal connection in the readers, moonlighting into the way we interact with architecture. As Gayatri Ganesh’s visual storytelling shapes Demello’s imagination, the readers ponder, draw parallels with their personal experiences and can arrive at their conclusions. Just as architecture integrates familiar functions within ever-changing and evolving spatial fabrics, Five Architecture Fables combines social, cultural and personal themes to challenge perceptions of architecture and cities that we actively experience at all times yet rarely fully contemplate.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Bansari Paghdar | Published on : May 30, 2025

What do you think?