Edgar Demello’s ‘Five Architecture Fables’ as a manifesto for oneness

by Bansari PaghdarMay 30, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Bansari PaghdarPublished on : Mar 26, 2025

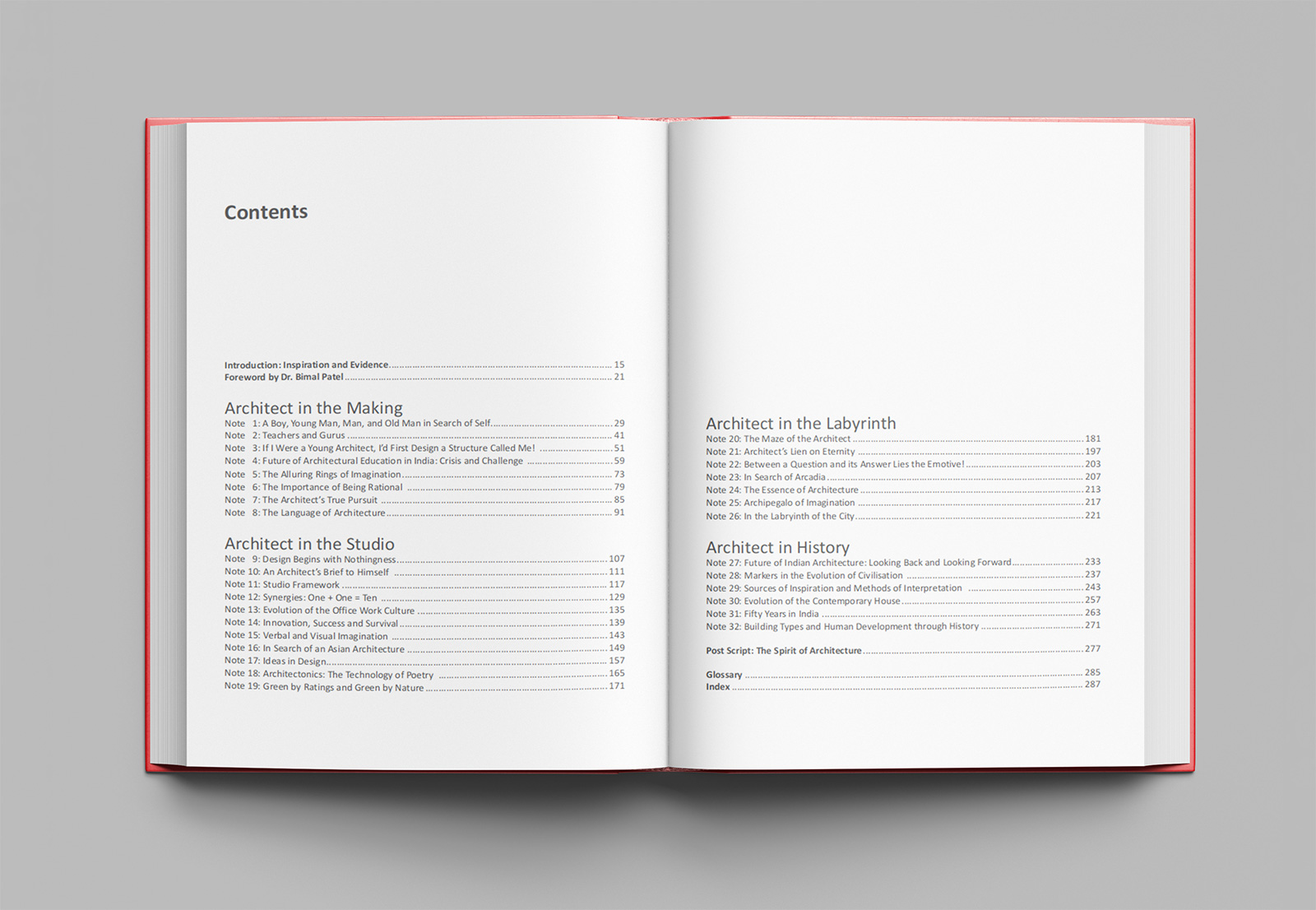

Completed and launched shortly before his passing in 2024, Indian architect, urbanist and academic Christopher Charles Benninger’s book, Great Expectations: Notes to an Architect, serves as a spiritual follow up to the renowned Letters to a Young Architect. While the latter was a quintessential read for the impassioned, untainted architect in us all stepping into or barely out of architecture school, the 'sequel' attempts to confront the difficult realities of the discipline in a manner that remains evocative of the distressing memories of several young and seasoned professionals in the field. Structured as a collection of articles, lectures and notes spanning the last two decades of Benninger's life, the book employs semi-autobiographical narrative tools—just as the prequel did—in an attempt to inspire and guide students and young professionals seeking to practice architecture, with all its opportunities and ailments, as the profession currently stands in India (and to a certain degree, the world over). Divided into four sections, the ‘notes’ delve deeper into Benninger’s life and philosophies, recollecting his journey of self-discovery, while presenting his opinions, understandings and concerns on the precarious state of design, architectural education and practice in the country.

Benninger’s pedagogy has always championed the image of the architect as a worker, away from their relegation to the perceived supremacy of a creator; as someone trying to get the job done. This is executed practically by passing down knowledge of building systems through generations and developing a systematic, technology-driven approach grounded in objective reality rather than romanticism. While this ideology is reflected in the majority of the text and in CCBA's vast portfolio, in some instances in the book, Benninger does return to explicating on “the genius of an architect”, arguing that “a moment of epiphany” merges “the spirit with the mind; in the transference from the mystical realm to the real world”. The somewhat sudden shift from promoting rationalism of systems to the romanticism of the ‘genius’, the ‘spirit’ and the ‘mystical’, doubles down to be more a stark reminder of the ever-changing, paradoxical and often absurdist nature of architectural criticism, ranging from architectural and design juries to the very practice of journalism in the fields.

Benninger counters young students’ perceptions of the discipline in the first book, reiterating these arguments in his ‘notes’. Perhaps the most romantic notion that all students and even graduates harbour is the belief that the conversion of their world-altering ideas into actual built environments or their constituent parts is not the mandate of architects; that architects are meant to dream of bold, innovative conceptual designs without worrying about how they will come to fruition. One could argue that this allows the architects to fully dedicate themselves to learning the ins and outs of design, prioritising user experience and emotion, spatial design solutions and aesthetic interventions—the intangibles of design—while leaving the ‘practical’ aspects to people who specialise in the technical production of the building. This ultimately leads to the production of professionals who, as Benninger critiques, are encouraged to prioritise replication—of styles, mannerisms and motifs to entire buildings under the futile art of the tribute—over innovation. Prevalent systems of education dissemination too actively encourage seeking inspiration from already existing designs and discouraging experimental approaches by deeming them impractical, illogical and unnecessary. Benninger’s arguments then make the case for an urgent shift in architectural pedagogy to radically reimagine ways of rethinking the built.

Perhaps the most lucid part of the book is the end of the first section Architect in the Making. “Architecture and city design are the venues of the good, the stage sets for pleasure and generic to the good life,” Benninger writes. He describes aesthetics as “anything that pleases the senses” and talks of the simple pleasures of life, the activities one engages in to find excitement and solace, along with the meaninglessness of being concerned with ethical enquiries in the absence of pleasure. Benninger calls out policymakers for attempting to control architects and suppress ‘aesthetics’ while espousing ethical beliefs, drawing parallels between a government enforcing prohibitions and dictating the personal lives of citizens, by governing who should marry whom, what films one can watch or what one can joke or not joke about, in a futile bid to curb interests and expression to protect their interests and beliefs, masking their flawed worldviews as the pillars of ethics and morality. Needless to concur, when one demands rights such as freedom of expression, justice and equality of opportunities, it is in the hopes of enjoying a ‘good’ life, prompting another personal reflection on one of my favourite TV shows of all time, The Good Place (2016-2020). Through the lens of Sartre’s ethics, it portrays the tension between pleasure and morality, suggesting that ethical living, instead of being about punishment or blind pleasure, is about meaningfully engaging with the ‘aesthetics’ of life, prioritising aspects such as relationships and personal growth.

When architects do the 'right' thing or the 'good' thing out of a sense of duty rather than seeking a reward, ethics simply become “questions to be answered”. Urging all designers, urban planners and architects to contemplate ethical questions by searching within, Benninger quotes the great Italian architect Donato Bramante, “It is better to seek the good than to know the truth!” Benninger views urban design and architecture as a “social and economic vehicle to bring the good to more and more people, equitably, justly and liberally,” looking towards all the stakeholders involved in the process. The author’s thoughts come full circle, back to the idea of people doing their jobs effectively. When places in the city become vistas of life, the built environments become extensions of one's inner selves.

The third section, Architect in the Labyrinth, provides most food for thought through its messages and musings. Benninger addresses the false promises of modern architecture and its ‘progress’ driven philosophy that aimed to uplift “Third World poverty into a Western middle and upper-middle class.” Instead, it ended up producing utopias modelled after Hollywood's portrayal of the nostalgic, visually pleasing American suburbs, as he laments. Benninger criticises the country for creating an oppressive urban fabric while dreaming of freedom, catering to “high-end, high art, expensive consumer urbanism”, underlining the need to put the less fortunate first—in terms of, say, housing and other related provisions—and looking back to the constituents of rural India to create new and relevant utopias accessible to all.

The section also includes Benninger contemplating and reflecting on his journey in a humble manner. He questions his decades of contribution and legacy, afraid that he could be cheating his gurus who entrusted him with theirs - a testament to the late Indian architect’s own groundedness. This makes one ponder on the weight one unconsciously may carry; of others’ expectations alongside one’s own.

The fourth section, Architects in History, begins by revisiting the past of Indian architecture to study the evolution of cities and building typologies, re-establishing the need to resolve the critical issues of affordable housing and access to basic infrastructure and amenities. With the help of this genealogy, Benninger begins to visualise a utopian future of Indian architecture, where the country will “find its roots”, “see lineal cities” and "employ less energy-dependent systems”. In the notes that follow, Benninger begins to explore the idea of “a truly Indian approach” towards architecture, providing case studies of projects his studio had undertaken over the years. While he raises important questions and makes valuable points on the history of modern civilisation and the manifold issues that the country faces in this section, the postscript seems to create a sense of disruption in the congruent narrative. Titled The Spirit of Architecture, the postscript sees Benninger talk about the 'genius’ of ancient India in “making the complex simple” and underlines how different humanity is from other species by creating, evolving and celebrating values that it creates for itself.

A host of rather personal reflections swarmed my conscience as I went through the book and its deeply personal but always affecting accounts. While finding a certain sentience in autobiographical narratives—used here as a means to manufacture an image of one of the greats in Indian architecture—I was increasingly reminded of my unpleasant years of architecture school and brief architectural practice as the book progressed; years that catalysed my transition from a curious, hopeful and spirited architecture student to a disconnected and somewhat lost young professional. An array of questions flooded my mind as I hoped to gauge a few answers from the book. Instead, I found myself with even more uncertainty than before.

A firm believer in the tradition of gurus (teachers) passing down their knowledge to shishyas (students), Benninger believed that the spirit of continuity is the essence of architectural education. Criticising the greed of institutions, he acknowledges the sheer lack of educational bodies that teach students how to put a building together during the exhaustive tenure of their expansive degree programmes in the book. Benninger reiterates that the country stands at a critical juncture in the evolution of architectural education, highlighting the destructive cycle that is created by the explosion of “a weak system of teaching” into an "incompetent, commercial production system”. The 'system' thereby produces architects that are unfit for practice, lacking essential skills, knowledge and the sensitivity—cultural, social, environmental, even political—that is essential to the way we build in the to-day and that institutes fail to impart, indirectly resulting in a multiplication of our urban and urbanisation woes.

In contrast to Benninger’s expectations for an ideal in education and practice to strive towards, the ground reality remains that most students are not in a position to harbour these great expectations to begin with. As per the Council of Architecture (CoA), there are 406 registered architecture institutes in the country. An Indian national daily, The Times of India (TOI), estimates that only 24,000 architects graduate each year, though there is no concrete data on how many of them go on to practice architecture. Apart from the dubious quality of training itself, architectural education in the country leans heavily towards commercial production as opposed to value creation, churning out more graduates than there are actual, meaningful employment opportunities. A number of unregulated institutions throughout the country continue churning out hopeful graduates without the requisite skill sets but laden with the aspiration to 'make a difference'. The bitter reality of 'climbing the ladder' or the 'rites of passage' of working on visualisations, the ever-popular toilet drawings and other seemingly inconsequential tasks (as opposed to the actual rigour in training and exposure) still awaits them. Despite this, in 2018, TOI expressed concerns about the country producing not nearly enough architects to meet the ideal quota for the ‘national architect requirement’.

Perhaps for many young students currently enrolled in the many schools of architecture in the country, having teachers who do their jobs efficiently, with humility, compassionate wisdom and educated perspectives is to be a blessing, as Benninger appropriately envisions in his text. The reality for these students (including myself a couple of years ago), as expressed, holds a rude awakening. A graduate of an average architecture school in an average Indian town, I am prompted to revisit my average college days as an average student. Professors and teachers rewarding students with work that satisfies an entire checklist of submissions of 'green', aesthetically pleasing 3D renders of a conventionally 'complete' building over messy, incomplete visions that does not fulfill said checklist remains a common occurrence, disregarding conceptual merit, if at all. It wouldn't be a stretch to infer that current architectural education privileges a sense of discordant but omnipresent emotional and psychological distress, bordering on abuse, with many choosing to transgress onto the person. The proverbial 'system', meanwhile, continues turning a blind eye to the goings-on in a majority of architectural institutions in the country that endlessly regurgitate decades-old ideas, instead of acknowledging that the current architectural landscape requires radical ways of doing. Can policymakers and teachers then—in both a personal as well as broader, pedagogical sense, take away from Benninger’s hopeful vision of a more inclusive education system? One can only hope.

Benninger’s reflections on urbanism, pedagogy and ethics provide valuable insights and spark critical discourse, even if they are not geared towards providing definitive solutions. Harbouring its fair contradictions and occasional meandering musing, the book contains clever anecdotes scattered across the notes, any of which hold the potential to trigger a chain of productive as well as reflective thoughts in the reader. On one hand, he underlines the importance of self-discovery and self-reflection; on the other, he drafts the ideal creative and practical process with ‘musts’ and ‘shoulds’ for students and young professionals to follow. By design or otherwise, the prescriptive tone that is inherent to this figure of the architect as Benninger outlines is bound to feel detached from the stark ground realities of the profession. It highlights larger urban development issues of the country without painting a utopian image, while rendering carefully how architecture must—profanely or profoundly—dabble with those. Ultimately, in all its contradictions, the book encourages its readers to forge their own path, both personally and professionally, while narrating the hopes and dreams of its author for a better future. Much like the younger architect readers of 'Letters to a Young Architect', Great Expectations too is a suitable coming of age.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Bansari Paghdar | Published on : Mar 26, 2025

What do you think?