Words, spaces & discourses: a look at the best design and architecture books of 2024

by Jincy IypeDec 20, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Nov 21, 2024

Everyone, almost everywhere knows the implications of ‘Make America Great Again’. And surely, everyone with a social media account happened to catch this summer’s fad, translated into a pithy campaign: ‘Kamala is brat’. While used in the election campaigns of opposing candidates in the recently concluded elections in the US, these slogans also represent the paradoxes of propaganda in today’s media (more accurately social media) saturated age. On the one hand, Donald Trump uses the image of a once ‘great’ America to polarise voters, while on the other, through the image of ‘brat’, Kamala Harris tried to portray a certain relatability, a friendliness to her (young) voter base. In their own ways, they try to shift public opinion, urging the public to think and hence vote in certain ways. In other words, propaganda (without the negative connotations for the most part).

Originating from the Latin, ‘propagate’ meaning to propagate or spread, the word first came into use during the 17th century Counter-Reformation. During this period, the Catholic Church tried to promote true faith, fighting growing heresy among the populace, with the Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide (the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith). Of course, the more common use of the term, to further political causes specifically would be seen during the Second World War when Hitler set up the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels which oversaw the content of press, books, art and other forms of media. The use of such controlled media was key to control or coordinate (Gleichschaltung) the German population. According to Hitler, the First World War had shown how important it was to understand ‘the emotional ideas of the great masses’, thus prompting him to find ways to move them, tapping into their predispositions and prejudices.

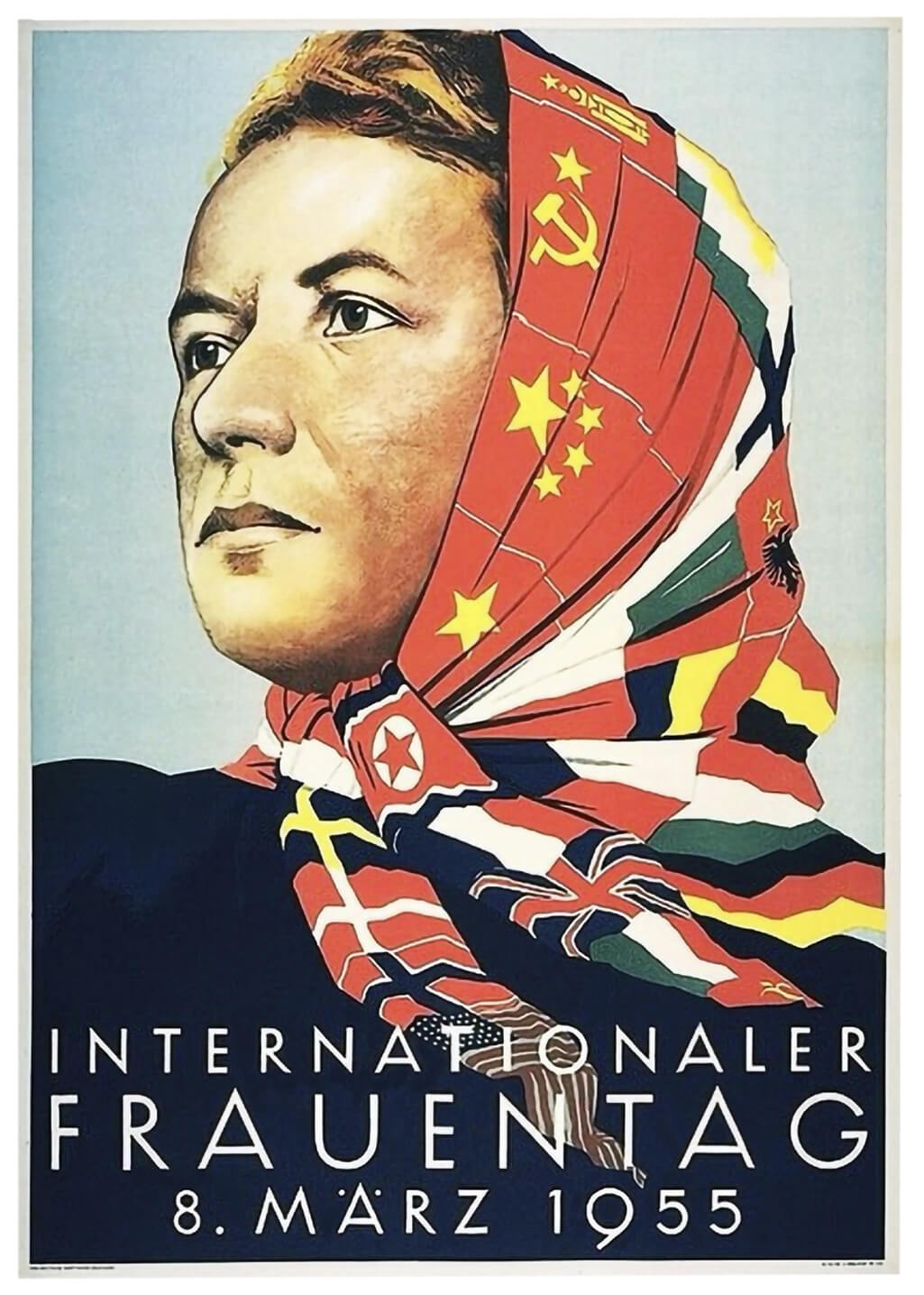

Goebbels claimed that propaganda’s power lay in "permeating the person it aims to grasp, without his even noticing that he is being permeated" reinforcing Hitler’s notion of the limited receptivity of the masses. By using Hitler to introduce the idea of propaganda, Robert Peckham in the essay that accompanies a new book published by FUEL Publishers, Propagandopolis, alludes to how it is often authoritarian leaders who have sought to use the power of such messaging to control the masses. The book is a compilation of what could be categorised as ‘propaganda art’; posters, manuals, murals and comics that issue health warnings or advice for the common public during war and more commonly political ideology. Unsurprisingly, a lot of the graphic art from the volume comprises war propaganda, as well as dictates from authoritarian states: fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, communist China and North Korea. Throughout history, rulers (and religious orders) have sought to glorify images of themselves through medallions, statues and paintings; very brat indeed.

Delving into the negative associations of the term, Peckham references an American PR pioneer Edward Bernays, who writes in Propaganda (1928) that “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society…Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.” In short, ‘free speech’ is dictated by the powers (or media) in charge. Freedom in slavery. This is countered by Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s ‘propaganda model’ which argues, “It is the media’s function to amuse, entertain and inform and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs and codes of behaviour that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfil this role requires systematic propaganda.” Democracy to them was represented by a society where self-serving media controlled information. Such a scenario seems only to have been exacerbated by the spread of fake news and the increasingly closed-off echo chambers that people on both sides of the political divide find themselves in. If the popularity of Trump or the brat campaign are any indicators, the spread of propaganda has reached a (if somewhat disjointed) peak with the rise of the internet.

The book provides major modern historical examples—taken from Bradley Davis’ Instagram account of the same name—in the form of pamphlets, posters, murals and billboards where the striking graphic design becomes a way for audiences to immediately connect with the message. Presented in alphabetical order by the countries where such artworks originated, the layout creates some interesting juxtapositions, not only between geographies but also between ideologies. With the many instances of propaganda on display, the reader is left questioning: how or why they are so influential or on the other hand so popular. On the other hand, would such propaganda still be relevant today? There are surprising instances that feel anachronistic throughout the volume.

The posters and pamphlets that depict themes of communism and Soviet ideologies hold the most interest for the author of this book review, graphically as well as thematically. For instance, a full-page spread created during the Space Age that depicts astronauts from the US and the erstwhile Soviet Union (now Russia) is particularly stunning. Painted by Dorzhiev Lubsan, it was meant to commemorate the success of the Apollo–Soyuz mission of 1975, when the US Apollo module docked with the Soviet Soyuz capsule, with the passengers spending two days orbiting together; ‘a new era in the history of man’, as General Stafford, leader of the US crew told his Soviet contemporaries. A poster from China similarly depicts a person gazing wonderingly at the sky as rockets jet off into space. Inscribed with the words Uphold science, eradicate superstition. First shown in 1999, it was part of a government campaign against the Falun Gong ‘cult’; a religious movement that rejects modern scientific principles such as evolution and modern medicine. Instead, their beliefs combine meditation and philosophies from Buddhist and Taoist traditions. The ‘heretical sect’ has been persecuted on the Chinese mainland (famously an atheist state) since the late ‘90s when the campaign first started.

Using mythic imagery to uphold the image of an authoritarian leader, a poster from North Korea portrays The Liberator of Korea. Vladivostok-based artist Vasily Galaktionov painted Kim Jong-un on horseback trampling the American and South Korean flags. This painting was gifted to Kim in 2013 by Anatoly Dolgachev, a communist legislator in Russia’s Primorsky territory and chairman of the ‘Far Eastern Association for the Study of the Juche Idea’. The inclusion of the painting in the book brings one to question how art can be used to manipulate the public perception of a leader, or only choose to depict narratives they believe in. Another interesting instance of a politically inclined graphic design asks the people of Switzerland to vote against the construction of nuclear facilities. Designed by Pierre Brauchli in 1981, it was one of several that were drawn in protest of the then-considered sustainable yet highly dangerous form of energy. While a 10-year moratorium was placed in 1990, every other referendum to ban nuclear energy in the country has been rejected.

Apart from political showboating and manipulation, posters related to health also have a touch of anachronism in their messaging. An anti-drug poster from the UK (referred to in the book as Britain, as it also includes instances of posters from Scotland and Northern Ireland) informs readers that ‘Normal People don’t need Drugs’ which was part of a campaign initiated by the Central Council for Health Education. Such contempt over and criminalisation of drug use continues to this day. A similarly darkly humourous poster from Thailand declares Women, socialising and liquor often lead to secrets slipping. An anti-gossip poster from the 1960s, drawn up by the Armed Forces Security Centre warns soldiers of the dangers of alcohol and debauchery in general. A poster from Uganda educates the public against AIDS. The activist artwork showing a soldier firing condoms into the air was part of a National AIDS Control Programme (NACP). Throughout the campaign, the government issued several quirky and somewhat unsettling posters such as these.

The funniest posters, however, are also the ones that are most out of place when looked at today. For instance, a British poster, part of the Liberal Party’s Liberal Europe Campaign (initiated due to the 1975 referendum) urges continued membership of the European Communities (EC). Ultimately, 67 per cent would choose to remain. Of course, this work takes on completely new meaning in 2024 and a post-Brexit world. Another poster, attributed to the US and designed by the chief graphic designer and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, Emory Douglas, depicts a period of activity of the activist organisation in the country and the fight for racial rights, still a topic of contention for the state.

While a lot of the posters, even taken out of their contexts, feel relevant in a way; depicting fear over war, health concerns, drugs, communism and anxieties over annihilation and control by terrorist groups, these parallels to contemporary situations border on almost humourous (at least to the author). They underline the fact that history does repeat itself. Looking at a poster of the Space Race and knowing what its outcome was—there is something prophetic in that, that the propaganda ultimately fails. Wrenched from their periods, the drawings and paintings feel like time capsules (occasionally naive) but also timely warnings, inviting the reader to think about the purpose of such graphic design and its meaning both within and beyond its era. Can any political art be created for completely altruistic purposes? Can it be considered aesthetically pleasing even if what it sells is unjust? Does such art only function when put into its context? What if the medium endures the message? Once revealed, can propaganda be fought and de-powered? And especially in today’s media-frenzied age, as Peckham points out, does the proliferation of images signal the golden age of propaganda or its end?

‘Propagandopolis' is published by FUEL Publishing and can be purchased here.

by Aarthi Mohan Oct 07, 2025

At Melbourne’s Incinerator Gallery, a travelling exhibition presents a series of immersive installations that reframe playgrounds as cultural spaces that belong to everyone.

by Asmita Singh Oct 04, 2025

Showcased during the London Design Festival 2025, the UnBroken group show rethought consumption through tenacious, inventive acts of repair and material transformation.

by Gautam Bhatia Oct 03, 2025

Indian architect Gautam Bhatia pens an unsettling premise for his upcoming exhibition, revealing a fractured tangibility where the violence of function meets the beauty of form.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 02, 2025

This year’s edition of the annual design exhibition by Copenhagen Design Agency, on view at The Lab, Copenhagen, is curated by Pil Bredahl and explores natural systems and geometry.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Nov 21, 2024

What do you think?