Delaine Le Bas on language and power, and making interactive art

by Srishti OjhaMay 30, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Verity BabbsPublished on : Jul 08, 2024

Brief Attempt, a two-day pop-up exhibition in Southampton’s God’s House Tower – a 13th century stone gatehouse that once was the city’s line of defence from the crashing waves of the sea and later served as a jail and mortuary – was the largest exhibition of work by the ZEST Collective to date. The group, now made up of 18 artists, was formed at the end of 2020 and has been creating and exhibiting artwork around Southampton. From their studios in an old pub, the collective, in their late 20s, have filled shipping containers with their work and created murals with the public in community gardens. Most recently, ZEST member Robin Price staged a solo exhibition inside one of Southampton’s rarely opened medieval vaults.

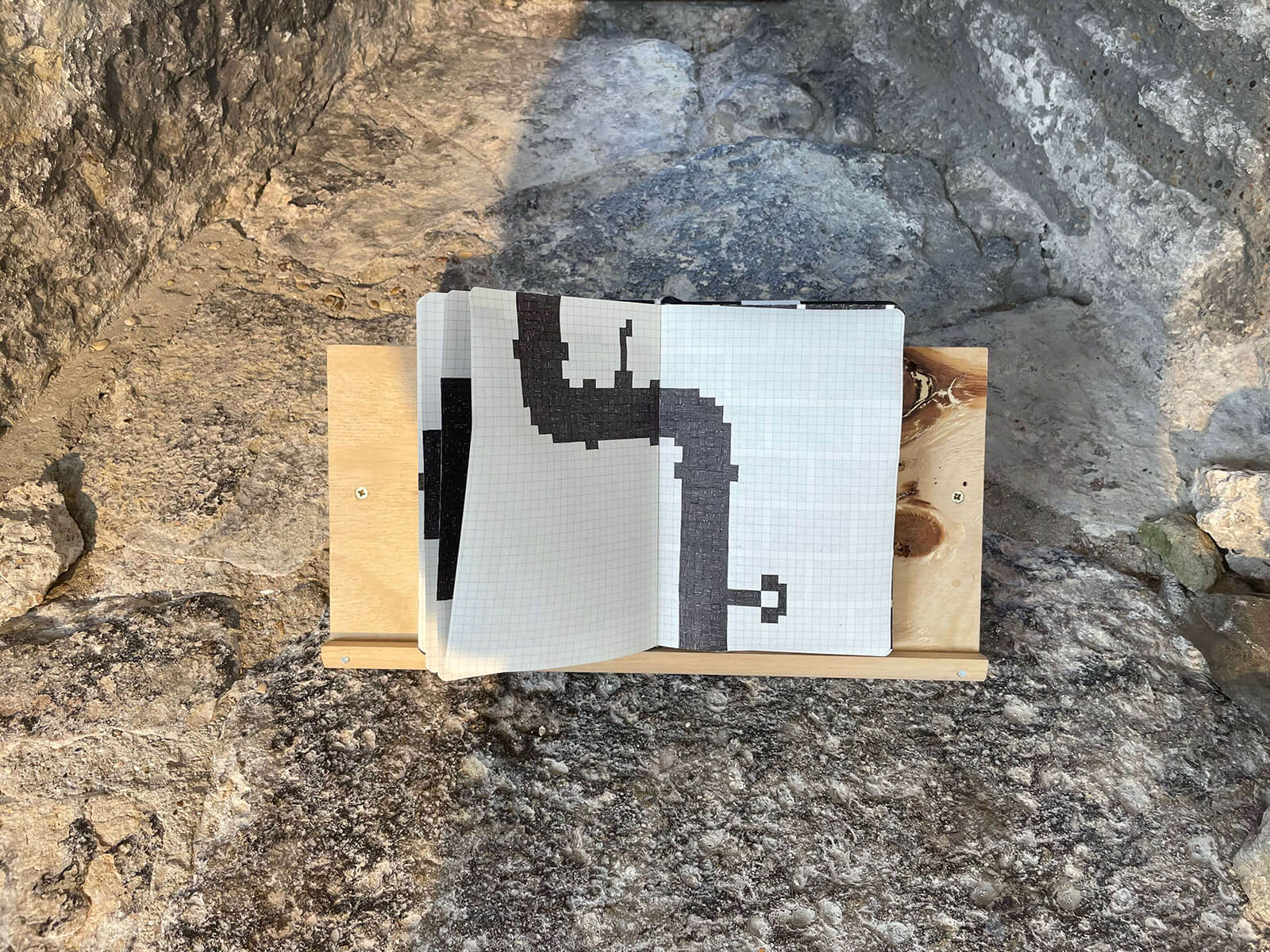

Brief Attempt grapples with a question that presses on any artist who has to work a second, third, or fourth job to sustain their creative practice – what time do I actually have to create work for this show? As part of the show’s curation, each artist declared next to their artwork the amount of time it had taken for them to complete the piece, ranging from 20 minutes to over 26,600 hours. The show itself was all about temporality: Alex Sutherland’s Socially Ltd (time: 20 hours, 17 minutes, 49 seconds) was a digital ticking wheel of hands, nostalgically cut out from photographs of the group’s social events; Net Warner’s plastic sculptures, Unvaluable and Desire Inverted (14 hours and 11 hours, 30 minutes respectively) melted into themselves, seeming to reference the imperceptibly slow decline common to all things on earth; Bryn Lloyd’s canvas, with blue acrylic paint, announced both boldly and sheepishly I ran out of time (time: 20 minutes). The show, which visitors could clock in and out of using an ‘80s employee time-recorder clock, was short-lived but very impactful.

With Brief Attempt, ZEST demonstrated the power of a well-run collective, but what do artists need in order to build their own successful groups, find supportive collaborators and broaden their opportunities for exhibition?

The ZEST Collective features many graduates from the RIPE graduate programme, a development scheme run by the local ‘a space’ arts, which provides local artists with exhibition and development opportunities. ZEST have successfully won 3 funding grants from Arts Council England as well as local commissions, and the group is held together by bi-weekly (at a minimum) meetings. Their studios are run out of Tower House, also owned and maintained by ‘a space’. Their members are friends and lovers. It is this level of structure, connection and funding (hard-earned) that allows collectives like ZEST to do what they actually set out to do: make art. But those opportunities can be hard to come by for grassroots and smaller collectives, with many funding opportunities requiring the collective to have a business bank account as well as considerable work already under their belt, plus the manpower to fill in the often-extensive application processes; and commission opportunities being largely tailored to applications from individual artists. The lack of opportunity for artists to form workable groups with longevity, affording them the opportunity to theorise and create, has arguably deprived the art world of the cohesive ‘movements’ that dominated the last 150 years of art history.

In 2021, for the first time ever each of the nominees for the Turner Prize were collectives: Array Collective, Gentle/Radical, Black Obsidian Sound System and Project Art Works. The artists involved in these collectives came together to work communally on their projects and other collectives like teamLab do not even list the names of the individual artists, programmers and engineers that make up their team. Collectives offer artists the opportunity to work together, supported by knowledge and resources that the group is able to share between themselves. The Jakarta-based collective Ruangrupa follows the practice of “lumbung”, originally a term for communal shares of rice in Indonesia; individual “majelis” (smaller groups within the collective) work with a shared funding pot, to compensate for the lack of funding opportunities and to reduce a sense of artist-to-artist competition. In comparison to this communal approach, the “collectives” of the past, the groups of artists pioneering movements and styles working under the same name and with a shared manifesto, like the Futurists, New Realists, or Surrealists, theorised communally but cultivated individual practices. A great collective has room for both joint projects and individual development supported by mutual influences and support from its members.

The “third place” was first explored by the American sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his 1989 book The Great Good Place. It described a third location separate from the home and workplace that he saw as needed for societies to thrive and function. The concept was recently resurrected on social media, with millennials and gen-z alike mourning the loss of these spaces, which included places of worship, working men’s clubs, community halls and cafes, due to economic constraints and the dawn of the internet which became in itself a third place but a poor substitute for actual human contact (as we all witnessed during pandemic lockdowns). Art collectives need purpose-focused locations to be available to them in order to support meaningful connection, room for creation and to foster artistic attitudes and ideas that develop the collective’s approaches. Third places have been the backbone of many of art history’s most major movements: Cabaret Voltaire, which gave a platform for some of the Dadaists’ most outlandish and boundary-pushing performances; New York’s Cedar Tavern beloved by the Abstract Expressionists, where artists like Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock socialised and developed their ideas until Pollock was banned for taking a door off its hinges and hurling it at Kline; or Paris’ Le Dôme Café which became a home from home for the Dômiers, authors and artists including Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Wassily Kandinsky, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso and Paul Gauguin. These locations have the potential to become the life-blood of a collective, and the loss of these spaces is disastrous in the long-term.

Having a shared philosophical mission can unite a collective, even when they are separated by distance, style and funding opportunities. Shared beliefs, fighting for specific goals and incorporating art into broader forms of protest are core to several flourishing collectives. Take InFems and the Guerrilla Girls, who are fighting for female parity on the global art stage as well as fundamental women’s rights. Shapes and Things are auctioning artworks to fundraise for aid in Palestine. It is a shared set of beliefs, whether they be about the state of the world or the theories of aesthetics, that can unify collectives, no matter how different the artwork created by the individual artists may be. These missions needn’t be theoretically complex and can simply be to create a meaningful artistic presence within a local area.

ZEST are doing it right, working in a structured way that allows for individual freedoms, influencing and assisting each other in the creation of their works. But, collectives like these, which are making a genuine impact on their local communities and creating artwork with the potential to make waves on a much larger scale can only flourish and reach their full potential with the continued financial support of larger organisations and governmental bodies, which must recognise the significance of art for community success. Not all groups making a meaningful impact are able to thrive or last – but even short-lived movements have made their mark on history.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Verity Babbs | Published on : Jul 08, 2024

What do you think?