Reflecting on 'sumud' as spatial resistance for Palestine in 'Their Borders, Our World'

by Mrinmayee BhootSep 06, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Agnish RayPublished on : Jun 20, 2025

The week that the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 opened to the public also marked 77 years since the Palestinian Nakba – the military operation that expelled 750,000 Palestinians and demolished entire towns and villages, eradicating traces of Palestinian presence from a newly forged national space. Carlo Ratti’s curation of this year’s Biennale invites audiences to consider the coexistence of human, natural and artificial intelligence in architecture and design. However, any questions among sector professionals of what or how to build cohesively and collaboratively today are haunted by Israel’s ongoing siege on Gaza that continues reducing homes, neighbourhoods, roads and infrastructures to rubble, while its assaults on southern Lebanon have also destroyed entire settlements.

Urbicide and domicide have emerged as key tactics in Israel’s attempts to make Gaza and southern Lebanon unliveable – but habitable space is not just about man-made structures. For certain exhibitors at the Biennale, the link between the natural and built environments emerged as the most compelling way to understand the spatial politics of occupation currently being witnessed in Palestine and Lebanon. Beyond understanding the aggression, configurations of meaningful lived and liveable space are also producing learnings on what resistance looks like in the territories and among their diasporas.

At Lebanon's national pavilion, the project titled The Land Remembers demonstrates Israeli attempts to turn Lebanon’s southern border into a ‘no man’s land’ in order to expand territory. The exhibitors emphasise that, while bombs devastate physical structures, the heavy metals they contain also contaminate soil and water sources. The natural environment is, therefore, the key target in a strategy designed to reconfigure borders.

“They want to colonise using nature,” says Shereen Doummar from the curatorial team, Collective for Architecture Lebanon (CAL), who has used research by the American University of Beirut and data gathered on the ground by environmental NGO Green Southerners to illustrate the environmental impacts of Israeli warfare in the region. The designer shows me a map highlighting locations along Lebanon’s southern border where the Israeli military has poisoned land and water since October 2023 by deploying white phosphorus, a chemical weapon that the team is campaigning to be fully criminalised under international law.

“Ecocide is a word that’s used a lot in international law”, says Edouard Souhaid, another member of the collective, “but in terms of architectural and spatial thinking, it isn’t really being taken into consideration.” He explains that many in southern Lebanon live off the land, which means that warfare targeting agriculture has more than just an environmental impact. “When you destroy an olive tree, you destroy the economy that comes with it,” he says. The team insists that architecture is not just about construction and technology but the natural land that undergirds any human effort to build. The exhibition exposes how the foundational structures of liveable life—manmade or otherwise—can be destroyed. “Before architecture, there’s land,” continues Souhaid. “You can always rebuild a destroyed home, but once you destroy nature itself, you destroy communities.”

As Israel’s latest plans to control Gaza crystallise, it is clear how its military operations are motivated by the spatial politics of territorial occupation. In mid-May, a map1 emerged dividing the besieged strip into three militarised zones, effectively imprisoning Palestinians within newly drawn borders. The Lebanese pavilion’s use of maps, therefore, feels significant and increasingly relevant, provoking visitors to consider the role of cartography in charting the violence committed by colonialist projects. It is particularly so for regions like Palestine and Lebanon, divided between Britain and France following the fall of the Ottoman Empire: through lines drawn by European nations, these mandated territories were spatially configured and reconfigured by forces of imperialism.

Maps also feature in a work by the Palestine Regeneration Team (PART) that forms part of the British national pavilion’s exhibition, GBR – Geology of Britannic Repair. Titled Objects of Repair, the project by Yara Sharif, Nasser Golzari and Murray Fraser charts geological exploitation in Palestine while also imagining the possibilities of resistance through reconstruction. Since 2009, PART has been addressing the fragmented landscape of Gaza and the West Bank through design-focused research; Golzari and Sharif also lead Architects for Gaza, which works on architectural education and rebuilding projects in collaboration with the Gaza Municipality.

“Colonialism is strongly related to exploitation of landscape,” Sharif tells me. The exhibition features three maps visualising how the Palestinian landscape has been ravaged by colonial powers through time. One shows an oil pipeline built by Britain in 1935 to fuel its Royal Navy; another from 2005 charts Israeli monopolisation of water and stone resources; the third illustrates Western oil corporations looking to exploit the region’s natural gas reserves today. Together, they show how extractivism strengthens, motivates and perpetuates colonial claims over territory. “Resources are power,” Sharif continues. “We can't separate architecture from climate, earth and resources because they are all forms of creating habitable spaces.”

Turning focus to the present day, the exhibition considers not just the enduring impact of historic colonial violence but how it is being endured today in practical terms. “Palestinians in everyday life are resisting occupation in different, small ways”, explains Golzari, “so it is important to show that there is resistance in practice.” The central installation is composed of replicas of ruins—rubble, reinforcement bars, corrugated metal, timber, fabric—sourced from sites of destruction during the architects’ visits to Gaza and the West Bank since 2010. These items are assembled to envisage possible means of repair and healing from the ruins of Gaza, reflecting how its population is recycling, restitching and rebuilding for survival and resistance. “We don’t have to wait for a ceasefire,” Golzari continues. “Rebuilding takes place all the time, every day.”

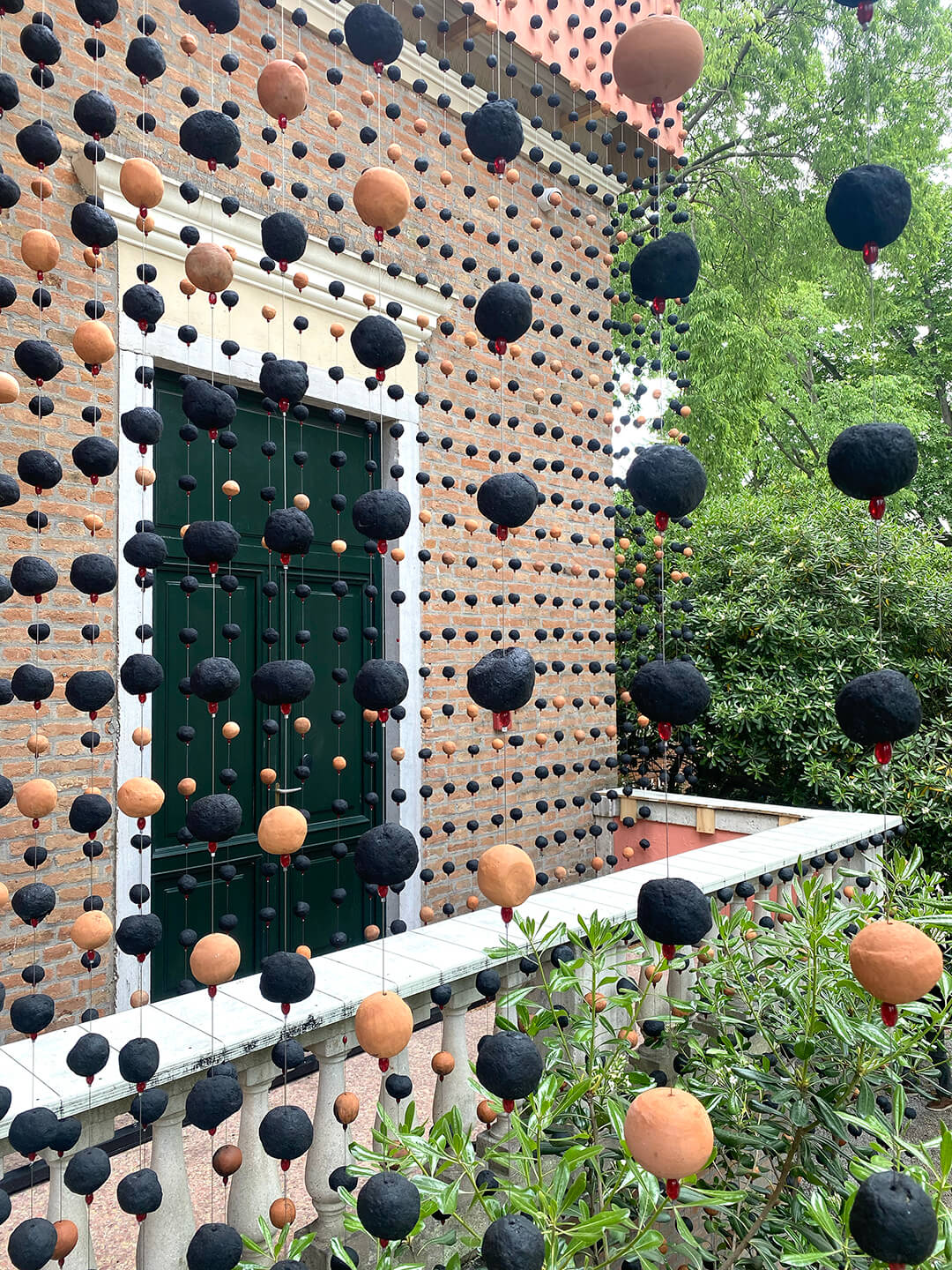

Palestinian designer Dima Srouji believes the objects of everyday life help construct the story of living under occupation and bombardment. At the Biennale, she presents her new project in collaboration with Piero Tomassoni, Gaza Shelters, which will comprise a series of structures exploring the notion of safety. These spaces of refuge will contain objects related to various spheres of Palestinian heritage, their ceilings engraved with images of the landscape of Gaza. “These structures are architectural at their core,” Srouji tells me, “but they also create intimacy between the landscape and the person inside.”

One of the shelters relates to agriculture, honouring roses, strawberries and other produce for which Gaza is known. “The relationship with the landscape is not just about farming but also tangible heritage,” says the designer, explaining that the distinctively dark clay used for pottery in Gaza reflects the particular kind of soil in the region. Another shelter will use gauze, whose etymology is believed to derive from the word Gaza, once made from a local kind of silk. “Even medical inventions are linked to the flora and fauna of the region,” Srouji reflects.

Whether through man-made habits, natural environments or national borders, the configuration of space has been central to Israeli occupation and aggression since 1948. But, spatial understandings can also propel resistance: for designers like Srouji, objects fully acquire their resistive potential once spatially manifested. “We’re creating a space where objects can live,” she says of her new project. “Space is where power exists. You can imagine what liberated Palestine might look like, but it doesn’t become a physical manifestation until you implement it in space.”

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.

The 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia is open to the public from May 10 to November 23, 2025. Follow STIR’s coverage of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 (Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective) as we traverse the most radical pavilions and projects at this year’s showcase in Venice.

References

1.https://www.thetimes.com/world/middle-east/israel-hamas-war/article/leaked-map-shows-israeli-proposal-to-force-gazans-into-three-strips-of-land-sjnn5nkbp

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Agnish Ray | Published on : Jun 20, 2025

What do you think?