2022 art recap: reimagining the future of arts

by Vatsala SethiDec 31, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Feb 22, 2024

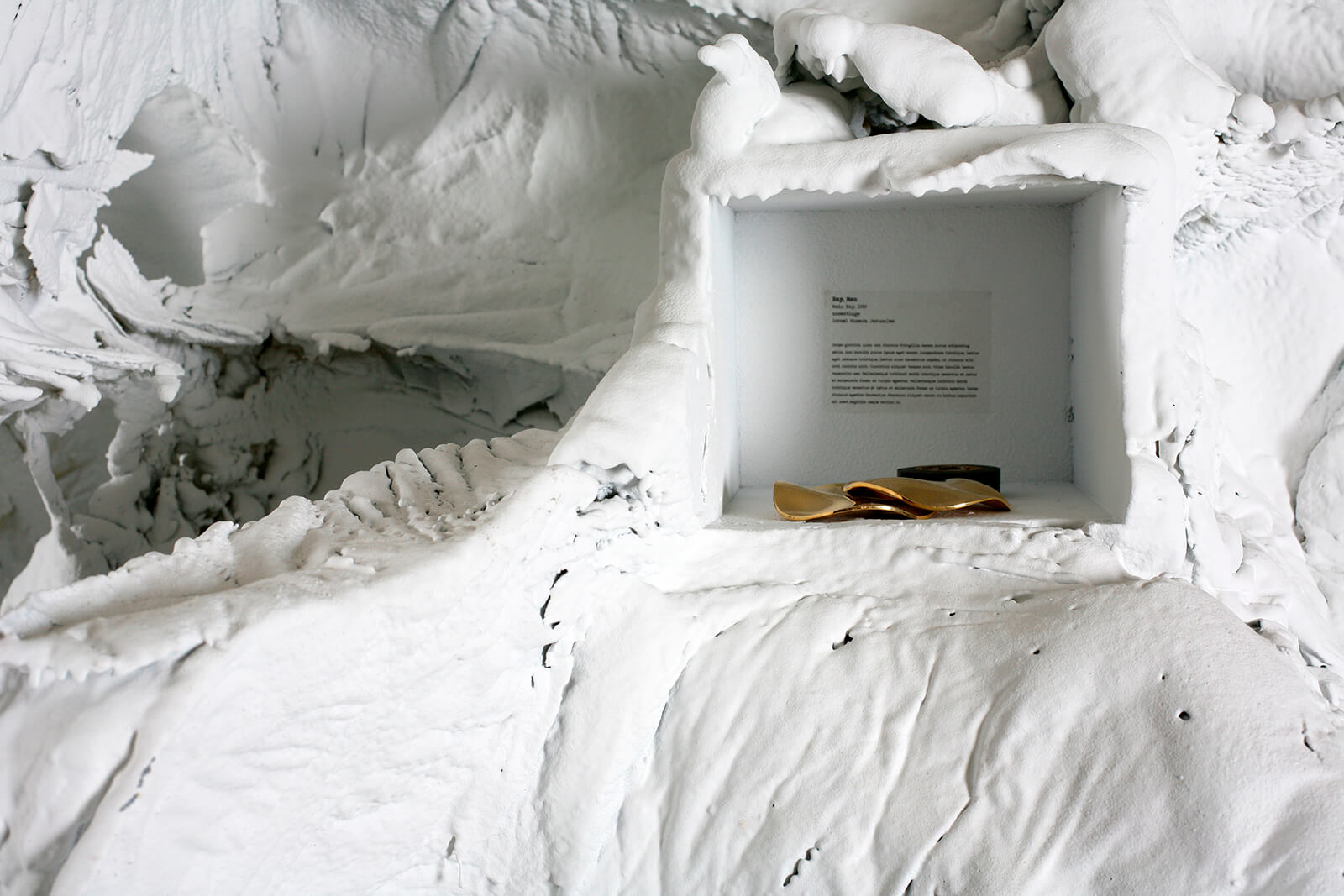

Architect and designer Omer Arbel works as an alchemist and inventor. Fusing different materials, he lets them guide the design process rather than relying on his imagination to make decisions that he thinks would be too willful and not rigorous enough. Take 113—all of Arbel’s projects are numbered chronologically—it is achieved by pouring molten copper into a glass form; once these two contrasting materials go through a fusion, they begin to cool at different rates causing the glass to crack open and reveal a richly textured copper substance. This largely unpredictable reaction of how one material behaves when it clashes and engages with another is a recurring theme in the designer’s work. After creating a whole series of captivating light fixtures, furniture pieces, glassware, candles, and jewellery, Arbel ventured into architecture, especially experimenting with concrete. "I want to build a form that occurs at the moment of material transformation. Spontaneous form-making is my goal," he told me during our interview out of the attic of his house in Vancouver, British Columbia, where in 2005 he started his double practice—Omer Arbel Office (OAO) focused on architecture and Bocci, a multidisciplinary design studio, both co-founded with his business partner, Randy Bishop.

Omer Arbel was born in 1976 in Jerusalem where his father ran a small law practice and his mother taught Mesopotamian mysticism and mythology at Hebrew University. He was initially drawn to architecture in part due to his interest in Bauhaus-style houses in Jerusalem; many were built by his great-grandfather who was a contractor. Interestingly, his mother grew up frequenting construction sites and even thought of becoming an architect but never pursued it. She maintained her love for architecture and passed it on to her son. “She opened a window for me into the magic world of architecture and I always wanted to become an architect,” he said during our interview.

When Arbel was 13 the family moved to Vancouver. He studied architecture at the University of Waterloo near Toronto. Known for its great apprenticeship model, the school enabled him to work in New York, Vancouver, and Barcelona before graduating in 2000 with two Bachelor's degrees—in environmental studies and architecture. In Barcelona, Arbel worked with Enric Miralles who inspired him to “invent a new language for every project again and again.” We discussed Arbel’s design process, collaborations with craftsmen, believing in continuous renovation instead of building from scratch, and how the virtual world will drastically change our lives.

I want each material to reveal its best qualities – Omer Arbel

Vladimir Belogolovsky (VB): When you talk about your work you use words and phrases such as mid-transformation, the act of exploding, metamorphosis, material discoveries, liminal spaces, making a familiar strange, alchemy, ambiguous boundaries, and constrained change. How else would you describe your work and what kind of architecture are you trying to work towards?

Omer Arbel (OA): Well, controlling the entire process is important to me. Initially, I could succeed in that only on a very small scale. An object can be pure and about just one idea. You can let the process dictate the meaning of a particular form. Architecture is more complex. My goal is to bring that intelligence into the scale of architecture. Architecture is about a hierarchy of ideas. So, my discoveries need to be done as parts of a composition of ideas. Unlike design, architecture needs to be forethought. The act of making occurs far into the process of conceiving, designing, thinking, engineering, acquiring permits, and so on. However, I am accustomed to complete freedom when it comes to working on a project. Freedom means control, a paradox but that’s the way it is. For example, if I want to design and sell a light, I set up my shop; I don’t send it to another store. It may sound like I am the biggest control freak. [Laughs] But when it comes to production, I let materials lead the process, although I set all the parameters. In any case, the cost of experimenting with architecture is very high. When I work on product prototypes I can afford to fail again and again. However, a building can be built only once.

VB: Your inventions typically emerge through the process of fusing radically different materials. How do you set such processes in motion?

OA: I struggle to make forms for form's sake, although I worked for Miralles and enjoyed it. I question the appropriateness of such exercises. I need to have a justification for a specific artistic gesture. Take Frank Gehry’s forms; they may be wonderful but it is not enough for me. They are labour and resource-intensive. But I always look for rigour, not intuitive willfulness. Why should the same forms be made in glass, brick, or titanium? Different materials have their logic. With enough money, anything can be done, but why? I would rather let each of these materials do what they want to do to discover amazing unpredictable forms that we could never imagine, and at a fraction of a cost. Fighting against material is expensive. I learned this firsthand. I want each material to reveal its best qualities.

VB: What about architecture?

OA: So far, I brought these ideas into architecture when I experimented with process-driven objects. For example, fabric-formed mushroom-like concrete forms were produced as objects, each holding a tree, and then I built relatively conventional spaces around them. That’s 75.9, a house. These giant objects look like sculptures inside the house. I find this relationship of organic interior and boxy exterior quite exciting. I want to continue exploring these ideas. I can even imagine their use in a public project, like a post office or a bus shelter. Imagine, a bus stop with a tree on top!

I am also looking for opportunities to create an entire structure as a process-driven object. I would like to be able to produce novel, strange, and never seen before forms and experiences. In other words, the intention is to bring similar logic not just to certain elements but to the entire building. I want the design decisions to be made by the material, not by the designer.

VB: You would write a script in a certain way and the composition would play on its own. Tell us more about this process.

OA: That would be ideal but it is challenging to get a permit for such a project. You need engineering, plumbing, and so on. In another project, we simultaneously poured mud on one side and concrete on the other. These materials have the same density, so they don’t quite mix. Then once the mud is washed away you get these incredibly beautiful forms and textured surfaces. Their beauty is in setting up the process; there is only a certain control you can have and every time the result is surprising. That’s why it is hard to plan these things. Again, a building cannot be pure, you need to have a kitchen, a bedroom, and so on. You can’t just make stuff and occupy it. I want to build a form that occurs at the moment of material transformation. Spontaneous form-making is my goal.

VB: Are there any architects who share your interest and inspire your thinking?

OA: There is Ensamble Studio in Madrid that works with concrete poured over stacked hay bales. Then there is Mark West, an architect and artist who pioneered fabric-formed constructions. My critique of most concrete architecture is that these buildings hardly ever show the fluidity of this material. Forms are designed independently of their dynamic nature. Formwork never acknowledges that. Although concrete is a pourable liquid. I want to see that. Tadao Ando may be successful in achieving silk-like beautiful surfaces but I want to acknowledge concrete’s sculptural potential.

In contrast, many architects are now interested in parametric technologies, 3D printing, and AI. I want the opposite—to do things with my own hands and the hands of the crafters. Pleats Please by Issey Miyake from the early 1990s is inspirational to me. The invention of a method of folding that made the dresses was a moment of great clarity. Those dresses are as much related to human bodies as to the process of folding. There is a material logic. Antoni Gaudi’s idea of inverting catenary curves in his upside-down study models is pure genius.

VB: Speaking of inventions, you said, “Our goal is to invent a process.” Can you elaborate?

OA: It is like a chef’s recipe. Different people bring their own ingredients, tools, characters, and emotions to their meals. There is a new taste every time. That’s what I want—every time the work is executed the makers bring something of their own. In other words, we develop a technique; we don’t control the form. We let the technique bring the form.

VB: You have said, “We believe in the enigmatic emotional potential of objects and spaces and we aim to focus and amplify this potential in our work.” Can you tell us more about this thought?

OA: I like the idea of imagining objects alive. Imagine if they could look back at us! Then we could have a relationship with them. You cherish them and they cherish you. When they break, you fix them. You wouldn’t throw them away. They would become our companions — tables, chairs, or mirrors. Buildings get built and demolished all the time. But why do we love ancient places and continue demolishing new ones? I believe we should renovate continuously. Therefore, we should build well. Spaces are rich because of what has accumulated in them—conversations, meals, rituals, and so on. Buildings soak lives and should be allowed to carry on this intangible humanism. I want to make objects and structures that are worthy of that level of interaction, cherishing, and inheriting. I believe in renovation as the purest form of architecture. I love Architecture Without Architects book by Bernard Rudofsky.

VB: What are your collaborations with craftsmen like?

OA: I rely on the forms that come from the material itself or a process, thus, I have to have great intimacy with each material I choose to work with. The only way to do that is to collaborate with craftspeople. However, I need to find not merely great crafters but also those who are willing to pursue my very naïve requests. [Laughs] I don’t know enough about materials and that’s why I want to experiment in ways that may lead to amazing results. We work with fantastic crafters. Together we are searching for truly transformative moments. I want to freeze a reaction occurring not before or after but in the middle of magical states of transformation.

For that reason, I thought of intervening in such a process on a molecular level. So, I reached out to Mark MacLachlan, Canada Research Chair in Supramolecular Materials and Professor at the University of British Columbia. He works with graduate students researching all kinds of speculative topics, some have no commercial application, and others do. We collaborate by sharing our facilities.

VB: What do you think are some of the most pressing questions for architects now?

OA: I think the transition to virtual reality is inevitable. It is just a matter of time, maybe possible in 20-30, maybe 50 years. People will have an entire universe in their minds. Already parametric technology and 3D printing are so advanced that anything we imagine can be made. People are obsessed with new ways of imagining virtual forms. Very soon we will be able to experience all that in ways that are not different from our material reality. This means that the architecture we know now is nostalgic. Architecture is a romantic past. What we do is the swan song of architecture. This is the end. But I am the last person to embrace it. I am still obsessed with making things that you can experience with your whole body. Nevertheless, very soon none of that will make any sense anymore. Just think about it, the inefficiency of construction takes enormous resources. None of that will be necessary anymore. This does not mean that the end is coming but certainly some sort of transformation. To be honest, I can’t wait to see it. [Laughs]

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Feb 22, 2024

What do you think?