Advocates of change: revisiting creatively charged, STIRring events of 2023

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Nov 28, 2024

Working within an 'un-civil' time requires new models of civility; a reimagination of the narratives of incessant progress wrought by capitalism and resource-extractivist cultures. They require a sense of civility towards local contexts and communities. They require new civic structures. This play between civility and un-civility is apparent in works by emerging architectural practice, Civil Architecture. Founded by Hamed Bukhamseen and Ali Karimi, the studio is based out of Kuwait and Bahrain (the respective countries Bukhamseen and Karimi belong to) and looks critically at the architectural landscape of the Middle East in trying to think how architecture might better contribute to this environment. Most vitally, their work is not limited to building; instead using design exhibitions, publications and research strands to explore architecture as an alternative model to the current moment.

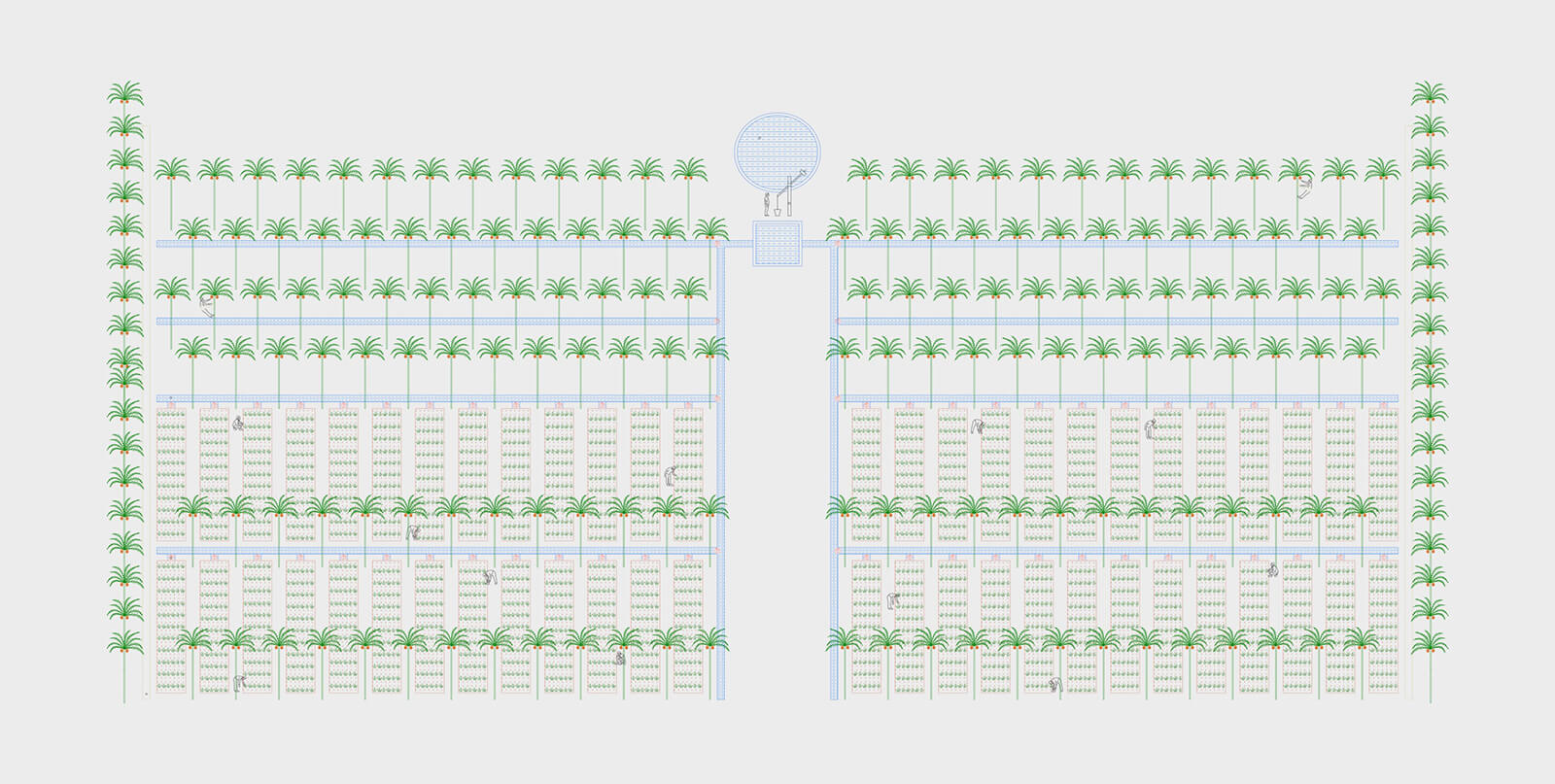

The duo’s work is centred on exploring (through research and architecture) the Gulf’s position relative to its global networks. Each project moves through thematic cycles; where in 2019 they investigated water-related issues (which was translated into an installation for Amman Design Week with studiolibani); in 2020, they looked at farmlands and urbanity. For the Islamic Arts Biennale in Saudi Arabia; the studio’s research dwelled on the temporal nature of seasonality. This theme was also alternatively explored in their installation for the Design Doha Biennial, A House Between a Palm Tree and a Jujube Tree (2023). While Sun Path, Rajab to Shawwal 1444 (2023) in Jeddah reinterpreted sundials traditionally found in mosque courtyards, the installation in Doha reinterpreted the traditional morphology of houses in the region to examine the relationship of residential architecture to the seasons.

Each work is also notable for its deceptive simplicity. In the design installation A House Between a Palm Tree and a Jujube Tree (also an ongoing building project), a roof becomes the primary morphological element of the residential design. The interior spaces are defined by a series of vaults and skylights through the suspended roof. For their showcase in Jeddah at the biannual art event, the duo created a system wherein the design tracked a ray of sunlight (rather than a shadow as typical sundials do) across the SOM-designed Hajj Terminal. The model was meant to highlight how communities realign their sense of time in the mosque’s public space; by presenting alternative methods of time-keeping more suited to the context. It came about from an earlier research project into agricultural and coastal landscapes.

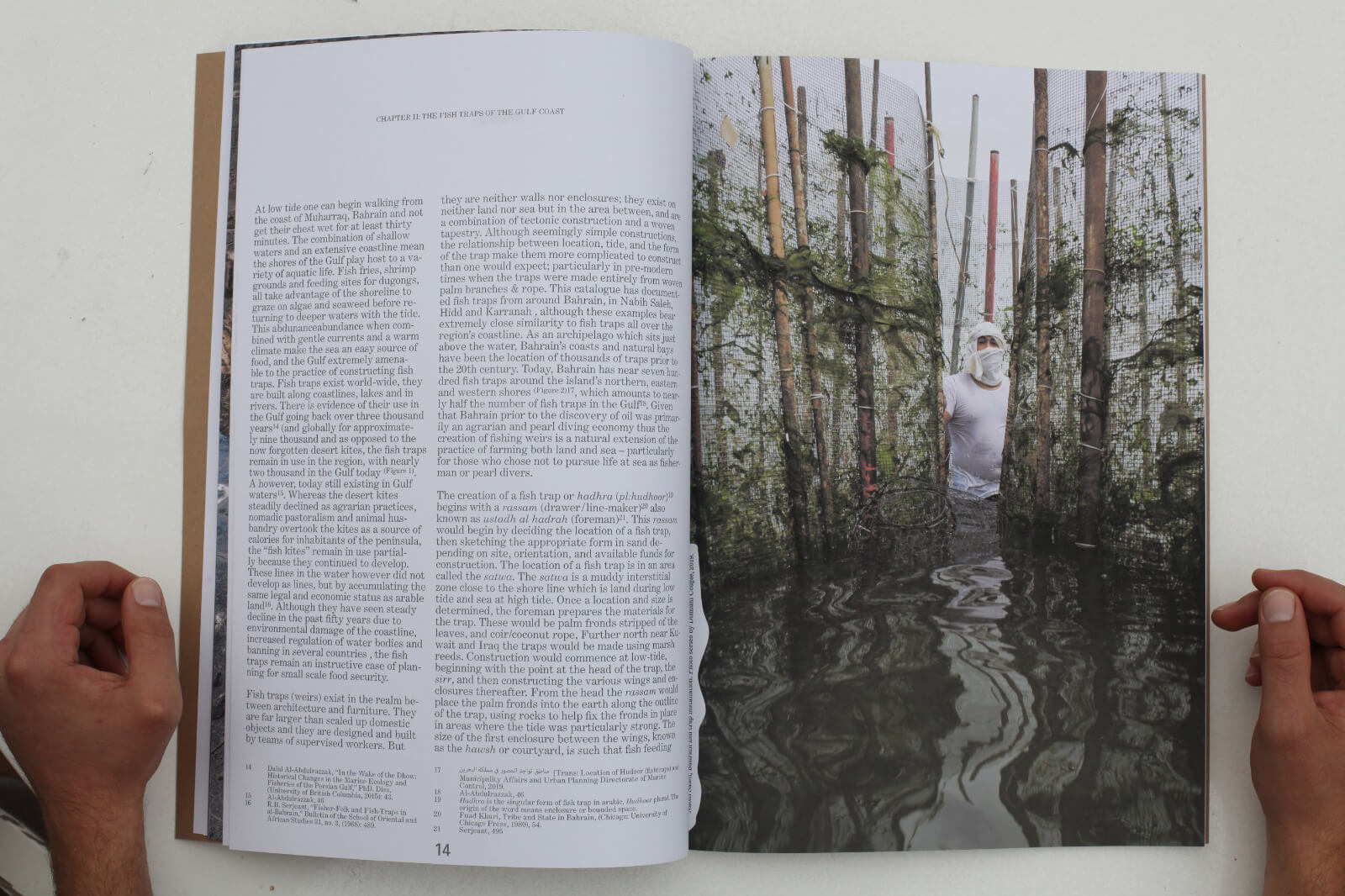

This early publication that was the result of the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale, Two Thousand Years of Non-Urban History (2019) delves into alternative ways of being that counter the reliance on technocratic solutions propelled by the dominant oil-based economies. Instead, it proposes vernacular practices that are embedded in particular territories. Contrastingly, a more recent book Foreign Architecture / Domestic Policy (2022) unravels how the oil economy in the Gulf links the region to global networks by examining infrastructure, namely Q8 petrol stations, built in Kuwait.

Through their participation in design biennales, design fairs and dissemination of research through books, the studio aims to portray critical takes on systematic issues and engender discussion within this larger cultural realm. This is the biggest way they hope to intervene in the built environment. STIR spoke to the duo about their research-driven practice, the landscape of architecture in a post-Dubai Gulf and their interpretation of the future. Edited excerpts of the conversation follow.

Mrinmayee Bhoot: Could you begin by enumerating how you started working together and what “narrative research” means for your practice?

Hamed Bukhamseen: We're a practice based between Bahrain and Kuwait. In a lot of the projects that we take on, we tend to create our own context; our body of knowledge before delving into any work. Research feeds into a lot of the work that we do and our work is always based on thematics that spread over two to three years.

Ali and I started working together in an official capacity in 2017. Since we're a practice that operates in the Gulf, we try to counter a lot of the expediency that tends to happen when it comes to the production of architecture that is so prevalent within the region: one that is purely speculative and driven by capitalistic gains. Ours is a formal practice which is slow and critical of a lot of things that are happening within the region. It calls to establish some form of agency for the architects where we’re more cognisant of our territory.

Mrinmayee: Can we dwell on your practice’s name? On your website, you mention, “The work of Civil asks what it means to produce architecture in a decidedly un-civil time.” How do you understand this play between civility and uncivility in architecture?

Hamed: Ali and I had been practising architecture abroad for a while. On returning to the Gulf, back in Kuwait, where I'm from and back in Bahrain, where Ali is from, we decided to take teaching jobs in the public universities of our respective countries. In that way, we thought of ourselves as civil servants. And we always found it interesting that civil and civility is associated with the public domain. We thought that sense of responsibility would be interesting to carry through within our practice.

Also, the translation of architecture in Arabic always prefaces the profession of an engineer. It's like an architect, architect engineer, or something along those lines. Whenever we talk about ourselves as architects in the vernacular, it always comes across as us being civil engineers involved with the direct construction of the built environment, as opposed to its design. The ‘uncivil time’ was a way to be critical of where we practice, as opposed to a judgment on the territorial situation.

Ali Karimi: I would say there's an aspect of humour to that sentence. On one hand, we understand ourselves as a practice whose focus is a distinction between the civic and the civil. Civic implies a certain typology and a certain scale of building, which we are interested in. But civil is more about the architect and his role in civil society. For us, that was also an important distinction. It was an aspiration to a certain mode of practice.

At the same time, by saying architecture for a non-civil time, there's also a need to not take ourselves too seriously. It is exactly about that kind of playfulness in how you structure your argument as a practice and present a new civic character for a global condition. For us, it's about pointing out the overlap between those names and questioning what each one of them does, while bringing a humorous tone to it.

Mrinmayee: Expanding on ‘un-civil times’, in your book Two Thousand Years of Non-Urban History, you write “Technocratic solutions to the problems of living have replaced practices entrenched in land knowledge”, which made me think of Neom and the controversies surrounding the construction of The Line. Could you elaborate on how your research counters this speculative narrative of architecture?

Hamed: We had just come back from Neom at the time, which definitely provided an insight into what “Gulf architecture” in hyperdrive looks like. It's Dubai hangover or the kind of construction frenzy that dominated in the 2000s and the early 2010s to a certain extent; which was written about extensively: OMA and other Western architects who came in and propagated the idea of the tabula rasa.

When we decided to take on Two Thousand Years of Non-Urban History, it was to counter the specific ideology expressed in that quote. It was to counter what we had seen in the past 10 to 15 years in the UAE’s built environment, that had spread across the entirety of the region: this real estate speculative endeavour and the practice of subdividing land to create property and de facto real estate. These practices were part and parcel of a lot of Western understandings of what it means to be inhabiting a region or a geography. What we saw in Neom was effectively the continuation of that project.

It was the reliance on the image, on the touristic aspect of living and inhabiting an environment. And we thought to ourselves, why not turn to something else? Why not begin to reference a different type of precedent—which was the landscape and historical aspects—of living within the peninsula?

[Two Thousand Years of Non-Urban History] also came about with frustration about who was authoring this notion of the present and the future and to some extent the past in/through architecture...For us, it was about asking: what should the present look like? What should the future look like? What are the issues we think should be dealt with? – Ali Karimi

Ali: It also came about with frustration about who was authoring this notion of the present and the future and to some extent the past in/through architecture. With the past, there’s some contention over who authors it, where you may have multivalent parties authoring different pasts. You at least have versions of the past which coexist. But as for the present and the future, it felt to us that those were increasingly, or actually, those were entirely the mandate of foreign studios or locally based developers looking to produce neoliberal capitalist-driven models originally envisioned elsewhere, like London or the US.

For us, it was about asking: what should the present look like? What should the future look like? What are the issues we think should be dealt with? And ultimately, it was also just a question of who gets to author those narratives. To touch on Hamed's point, there's a promise of a future in projects like Neom, but it's not very clear. I believe it's unclear because this is true for everyone: what the future of those places are and who they're meant for is extremely murky, except that they're meant to be seen as an argument for a certain kind of living. For us, the book was about asking where the break from the current ideology (that was dominated by the discovery of oil) might be and asking what visions of the present can be possible outside this.

Mrinmayee: That’s a brilliant answer. Speaking to this notion of the present; with the rise of design biennales such as Design Doha or Islamic Arts, how do you see the landscape of contemporary architecture discourse in the region or globally changing?

Hamed: It's an interesting moment to be operating in the Gulf. Increasingly, these kinds of design exhibitions have allowed us to kind of enter the cultural sector, which has fostered a lot of the initial ideas from which we deploy our research work and ultimately garner a clientele base to allow for the larger projects to come into play.

Ali: To echo Hamed's point, it's exciting because it's the first time you have a funded venue to be able to think about architectural ideas at a certain scale. Before this moment, you'd either have to look abroad or you'd have to look at self-funded initiatives. In that regard, it's great because it means there's room for the creation of new, smaller sets of ideas in the region.

On the other hand, I think the biennales model also reinforces a certain kind of expedited, quick box-ticking approach to design thinking. And I don't think it's the biennale’s fault, but just how they are run sometimes. For me, it's more about this question. My concern with the biennale model is less the biennale itself: Who's invited? How much time do they get to prepare? How do you build long-term projects? How do you ensure that they're sustainable?

Mrinmayee: While situated in the present, your work also presents alternate visions of this reality. Often, architecture is burdened with having to come up with solutions to the world’s crises.

We’ve also spoken thus far about the spectacle of Neom and its reliance on this very ‘solution’ model. To that end, I want to understand how you envision the future in your practice.

Hamed: The reality is it's a systemic issue. I believe, as architects, we should not be overburdened with this idea of trying to fix the climate crisis or resource scarcity; but facilitated to produce an empathetic architecture: one that is willing to understand its position within the entire ecosystem.

Ali: Adding to Hamed’s point, say you took all the architecture done by practices who think of architecture ‘critically’, it probably comes up to like 0.01 per cent of architectural production globally. So you could work on what you understand as sustainable design, but there's a larger systemic question that needs to be addressed. And this idea of guilt, that it’s on the level of the consumer is not just architectural. Say, if recycling plastic bottles on an individual basis would solve the climate crisis and I do think it helps.

I think the ‘solution’ model comes from a particular idea about the future, which I believe is fundamentally broken. In our practice, we try not to think of it because it's an idea of the future that's in service of unchecked growth. It's in service of the proliferation of bad economic models. The idea of the future in the Gulf is so broken that it's untenable. Instead, we like to think of our practice as being situated in the long present. The issues we try to deal with are issues that exist in the present and their solutions can be in the present or in the near future. For example, finding ways of building that don't require as many resources. We're working on a mangrove nursery now and looking at ways of having the nursery not use any water. This isn't an impossible technological solution.

It would make it much more sustainable than the nurseries that use desalinated water or treated sewage effluent. It's much more useful for us to try to solve these problems in the present and imagine our cities and our way of inhabiting the world in a better present. The problem is this idea of the future offsets the problem rather than trying to solve it in the present on a person-to-person basis in some ways. At the same time, it prevents us from figuring out the problems that can be solved as architects like the quality of life for buildings.

This again touches on Hamed’s point about empathy. If the ultimate goal was purely sustainability, we’d be building our structures out of recycled plastics. It’s more about a quality of life and a way of inhabiting buildings that's fundamentally more sustainable. I think that's where we're trying to operate within this kind of long present and within the values that this long present could be improved on.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Nov 28, 2024

What do you think?