Tokyo Clubhouse explores the Japanese adage of mutual autonomy

by Dhwani ShanghviFeb 08, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Jerry ElengicalPublished on : Oct 08, 2025

On a tourist-saturated stretch on West 53rd Street in New York, a porthole-windowed white box playfully peers through the glass façade of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). But this isn’t any random box. It is one of only 23 ‘capsule’ housing units recovered from the famed Nakagin Capsule Tower. This particular capsule—named Capsule A1305—once sat near the bevelled bulkheads on the Nakagin Tower’s top floor, but it was salvaged and restored after the building’s demolition in 2022. MoMA acquired it in 2023, and since July 10 of this year, it has been on display in a quiet street-facing gallery, tucked beside MoMA’s lounge and ticket counters, as part of an exhibition at the museum titled The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, on view until July 12, 2026.

An icon of the Metabolist movement, the Nakagin Tower’s pixel-block silhouette once marked the southern gateway to Ginza—an upscale commercial district in Tokyo. Commissioned by the Nakagin real estate company, the tower was built to provide pied-à-terre accommodations for commuting businessmen, and it was designed by a team of architects led by Kisho Kurokawa. Kurokawa was the youngest founding member of the Metabolists, a group of Japanese architects and theorists which included the likes of Kiyonori Kikutake, Fumihiko Maki, Masato Otaka and Noboru Kawazoe. They released a rousing manifesto in 1960 declaring that “human society is a vital process” and that “design and technology should be a denotation of human vitality”. At the time, Japan’s fast-moving cities were expanding rapidly to support increased urban migration amid land shortages and a postwar economic boom.

In response to these changes, the Metabolists’ vision of a new architecture overrode the old Vitruvian ideals of stability and permanence, imagining buildings as dynamic, impermanent, evolving entities, akin to living organisms. The exhibition at MoMA mimics this biological metaphor and narrates the Nakagin Tower’s life cycle through the restored capsule and a selection of photographs, marketing materials, drawings and models, curated by MoMA Assistant Curator Evangelos Kotsioris and MoMA Curatorial Associate Paula Vilaplana de Miguel. In conversation with STIR, Kotsioris explained that after speaking to the tower’s past residents and consulting archival materials for his research, the “idea of the lived experience of architecture” became (for him) the most interesting aspect of the Nakagin Tower’s story.

To depict the relationship between the tower’s design and the lived experiences etched into its structure (as well as derived from it), the curators split the architecture exhibition into two segments. The first covers the tower’s design and construction process, illuminating how the design team—which included architects Nobuo Abe, Aiko Mogi, Koji Shimosawa, Kenjiro Ueda and engineer Gengo Matsui—dreamt up the kinds of lives the building’s future tenants would lead. Their design prescribed a particular way of life for the tower’s users. Kurokawa, like many Japanese architects of his generation, had imbued his architecture with prescriptive (and sometimes inflexible) design features, taking from earlier modernists, including the writings of Le Corbusier. Historian and critic Mark Wigley once summarised modern architecture’s prescriptive tendencies when he wrote that Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture (Toward an Architecture) (1923)—a foundational modernist treatise—turns “a description of what is happening in modern life into a prescription of what should happen in architecture”.

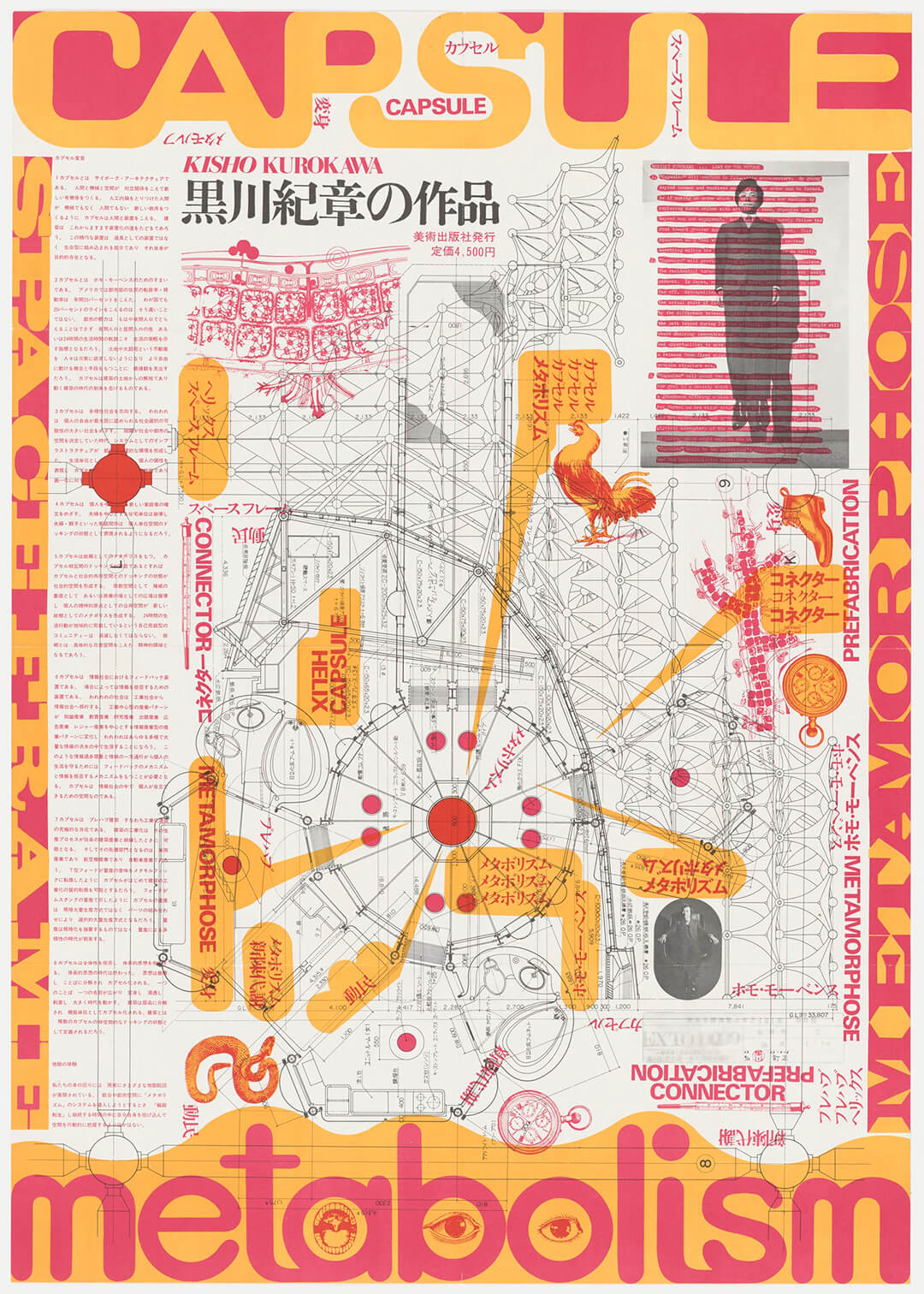

The opening segment of the exhibition delves into how Kurokawa’s version of ‘capsule architecture’ married this Modernist notion with the thematic biomimicry and impermanence of Metabolism. In the exhibition gallery, a bright orange room divider hosts a fold-out poster featuring Kurokawa’s seminal Capsule Declaration (1960) text, alongside drawings for the ‘Capsule House’ Theme Pavilion at Expo ‘70 in Osaka. Kurokawa envisioned capsules as ‘independent shelters’ for individual users that were prefabricated and docked into larger structural systems. This kind of architecture could transform and expand infinitely, with its autonomous fragments coalescing into a larger whole, like cells combining to form tissues and muscle fibres. In Kurokawa’s own words, capsule architecture was “a group form which expressed the individuum”.

The Nakagin Tower’s design emerged from this premise. Its skeleton consisted of two reinforced concrete service cores that were connected by bridges every three floors. Plugged in to these cores were 140 factory-made capsule housing units (measuring 2.5m x 2.7m x 4.2m), designed in eight different configurations. Each capsule’s enclosure was made up of galvanised, rib-reinforced steel panels fitted onto a steel truss box. The capsule’s interior contained aeroplane lavatory-style bathrooms as well as built-in furniture. Everything from the appliances to the decor was customisable, and the capsules themselves were supposed to be swapped out after 25-35-year-long ‘metabolic cycles’ as residents’ needs evolved. At the time of the tower’s completion in 1972, this was a radical idea.

However, scholars such as Zhongjie Lin have since pointed out how Metabolist buildings were “less economically viable” than their modernist peers because their unique façades—designed to represent each occupant’s individuality—left them with less usable floor area per level. Lin also noted that the clear distinction between a capsule and its structural frame offered “little flexibility in terms of occupancy and structural expansion”. While these issues eventually contributed to the Nakagin Tower’s decay and demolition, they also prevented the tower from evolving as Kurokawa intended.

Near the Capsule Declaration poster in the exhibition, a cherry wood and brass model of a planned expansion for the Nakagin Tower shows the building morphing into a megastructure in a future metabolic cycle. The tower’s initial success prompted the developers to enlist Kurokawa for an expansion project. But it never materialised into built form because construction costs rose steeply during the 1973 oil crisis, and home buyers’ preferences changed.

In a neighbouring corner of the exhibition, a projector plays a promotional film in which Kurokawa talks about the tower’s conception. At the end of the film, a brief marketing montage shows a Japanese salaryman dressed in a dark suit strolling into the building’s lobby, checking his mailbox, going to his capsule and enjoying some solitude after his 9-to-5. “We often think about architects designing the bricks, mortar or geometry of a space, but when they design, they also imply a specific kind of occupant for it,” notes Kotsoris in response.

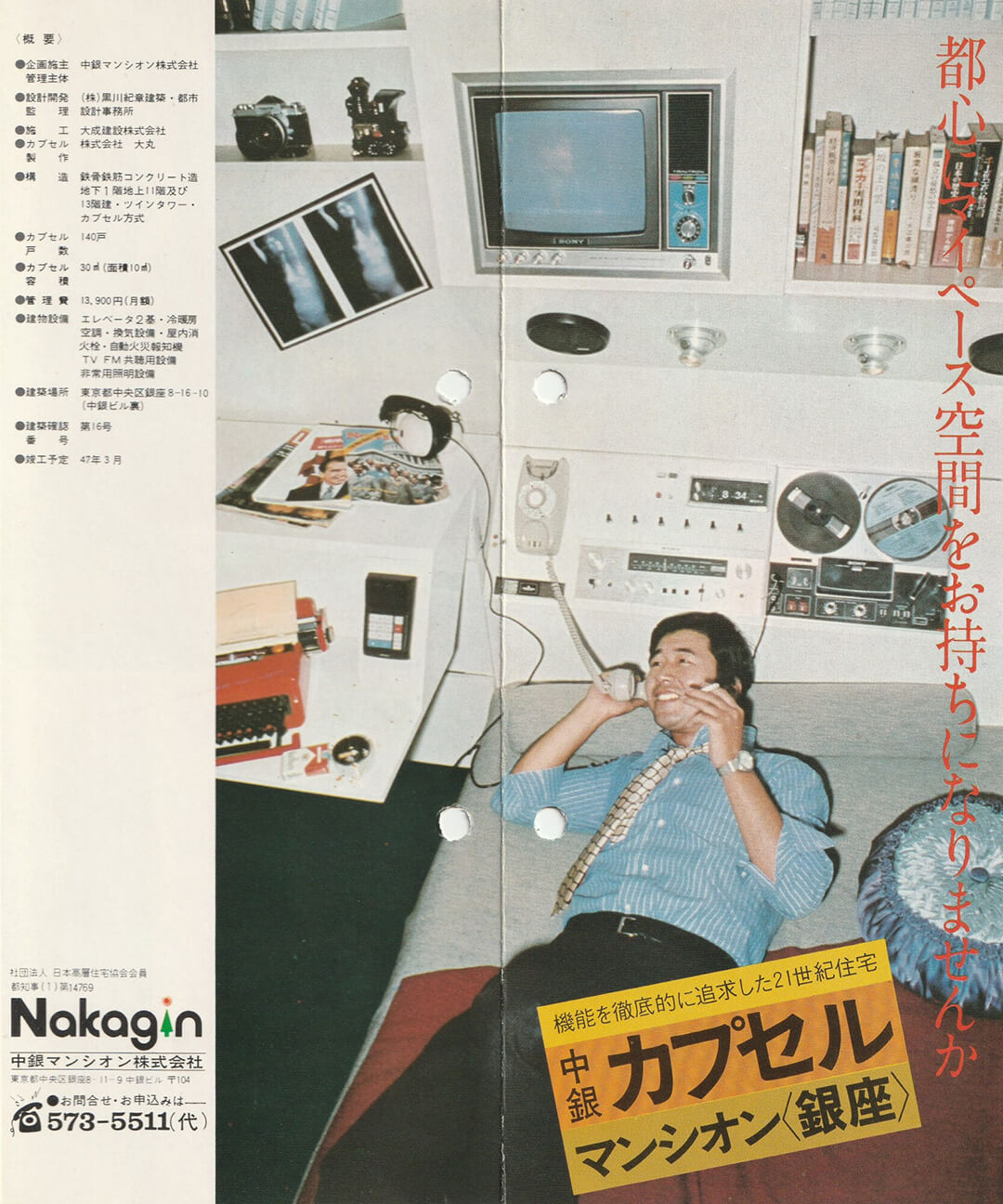

The developers and Kurokawa pictured their tenants—predominantly working bachelors—living mobile, liberated lives that weren’t anchored by permanent dwellings. Kurokawa christened this class of urbanites as ‘Homo movens’—humanity in constant motion. The Nakagin Tower’s drawings and marketing brochures advertised this lifestyle through the visual language of car catalogues, just a few years after architecture critic Reyner Banham remarked that “the car was already doing quite a lot of the standard-of-living package’s job”. Unfortunately, this futuristic vision still hadn’t outgrown old-fashioned patriarchal gender roles. The 'Homo movens’ lifestyle cast women as the Nakagin Tower’s concierges and support staff, or the homemakers stranded in suburbia while their husbands gallivanted across Ginza. Such anachronistic shortcomings recur in both the Nakagin Tower’s design and in its story.

After an initial period of high occupancy, the Nakagin Tower’s tenancy levels petered out over time, and most capsules were empty by the 2000s. Without maintenance fees for upkeep, the building fell into disrepair, and the tower spiralled into a midlife crisis. Renovation plans were rendered unfeasible due to a structural issue that prevented individual capsules from being pulled out and replaced independently. There was also the high cost of removing the building’s asbestos insulation (which Japan had banned in 1975). As rehabilitation schemes reached an impasse, the focus shifted to redevelopment. Following Kurokawa’s passing in 2007, there was a lengthy legal battle between capsule owners and developers over what to do with the building. Finally, after a failed effort by residents and non-profit organisations to lobby for the building’s preservation, the Nakagin Capsule Tower was pulled down to make way for a new development (a Pullman Hotel) on its site.

If the exhibition’s first section covers the Nakagin Tower’s birth and infancy, the following segment commemorates its adulthood, death and afterlife. Posters, memorabilia and video interviews with residents tell the stories of the building’s diverse inhabitants: a DJ, a former chamber of commerce manager, a designer, a filmmaker and a writer. All of them found versions of home and community within the capsules. Some used the living units as offices, and a few of the tower’s ‘pink’ capsules were also used by sex workers to conduct business. Echoes of these lived experiences linger in photographs from Noritaka Minami’s series titled 1972, which depicts the tower’s final years and culminates in images of its demise. These images render a portrait of a building that meant many different things to many different people. But can they authentically convey the many lived experiences that emerged from the Nakagin Tower’s architecture?

Walter Benjamin once wrote that the authenticity of a thing “is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced”. Now that the Nakagin Capsule Tower is no more, how many fragments of its history are enough to convey an authentic essence of the whole? And how does each fragment’s physical and historical context affect its authenticity?

Following its separation from the Nakagin Tower’s service core, Capsule A1305 has taken on the properties of an objet d’art when seen from the street. Kotsioris described the capsule as a “pure white modernist object”, whose outline becomes legible through the “splash of pop colour” imparted by the gallery’s coral pink walls (the original colour of one of the tower’s stairwells). According to him, this arrangement mimics the tower’s meandering service core, making visitors feel like they’re “trapped in the stairway” in an abstract sense. But instead of the capsules surrounding the stairway, the stairway wraps around the capsule. Such an inversion of the bond between the capsule and its anchoring structure is only possible because the capsule is a de facto, independent modular unit. And on viewing the capsule up close, it becomes clear that this autonomy supports an additional function. Mirroring how it was designed as a customisable blank slate for a future user, Capsule A1305 too became an empty canvas on which the curators could paint a picture of a past occupant.

The curators wanted the capsule’s interior to feel lived-in, and they staged it in a way that would depict the sociocultural background of the tenant Kurokawa designed it for: a cosmopolitan, multilingual, white-collar worker in Tokyo during the 1970s. Kotsioris said they achieved this by consulting the Nakagin company’s promotional materials from 1971. As part of their staging, the wall at the end of the capsule’s built-in bed features an Expo ‘70 Osaka poster. A fold-out desk hosts an Ettore Sottsass-designed Olivetti typewriter, a Sharp calculator and copies of LIFE magazine and Newsweek. A Sony TV is housed in the wall above, while a landline phone, sound system and a reel-to-reel tape recorder are built into the bed’s headboard. It’s like Kurokawa’s ideal tenant never left.

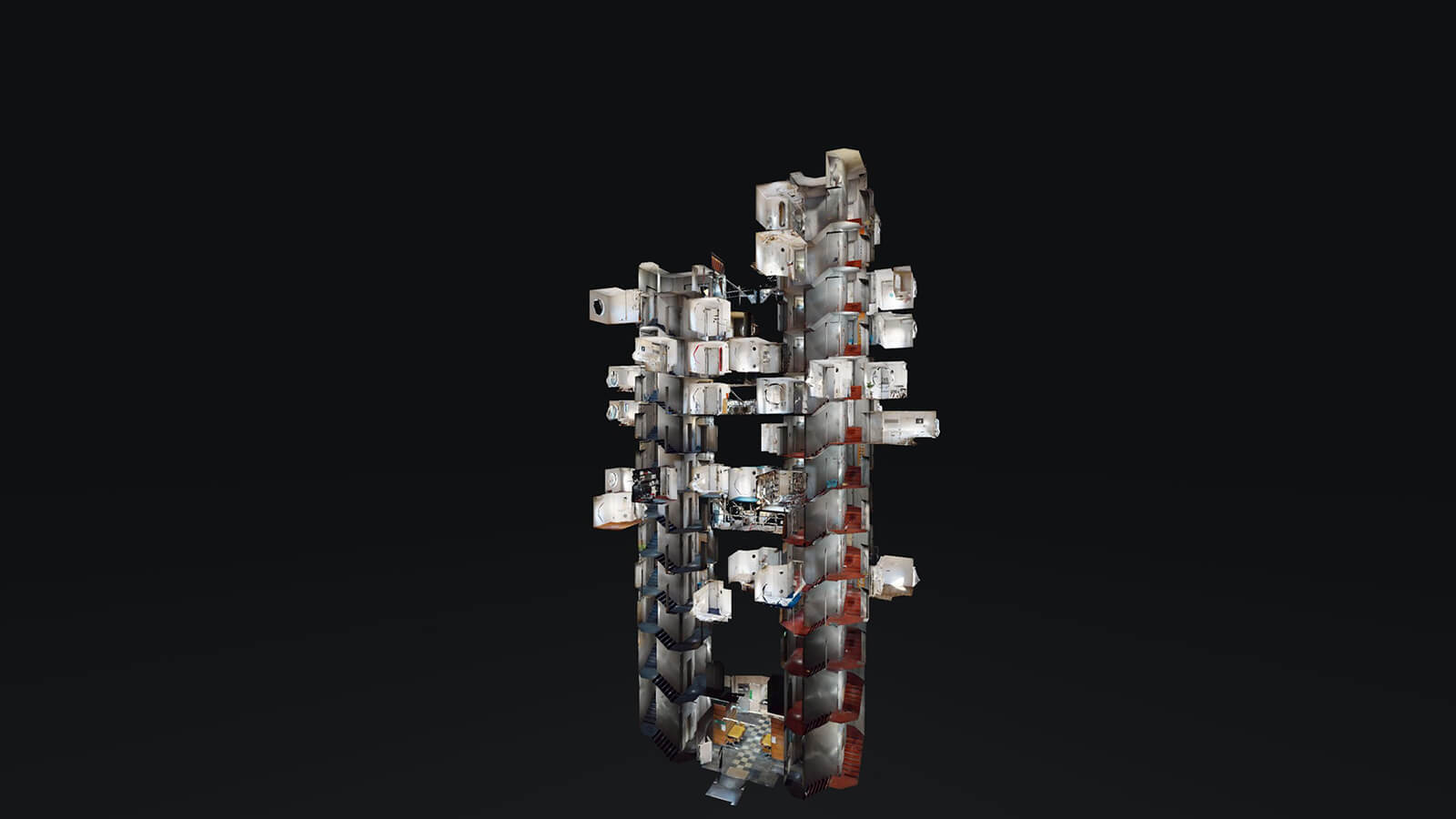

But we know that’s not what actually happened. Days before the building’s demolition, a group of former residents salvaged capsules that were still in good condition (some have found new homes in cultural institutions across the world). They partnered with Yuta Tokunaga, a specialist in 360-degree architectural documentation, to create a digital model of the tower’s interior using photogrammetry. The model is on view in the exhibition as an interactive 3D map, allowing museum visitors to wander through the Nakagin Tower’s lobby, explore its dimly lit stairways, inspect the faded paint on its walls and even gaze out at the Tokyo skyline through a capsule’s porthole window, rendering perhaps a more accurate view through digital fragments.

These distinct yet interconnected scenes—the capsule’s staged interior, the interactive model and Minami’s photographs—frame the Nakagin Tower’s essence through separate lenses. Together, they’re somewhere between continuous narrative and themed anthology, made up of fragments both virtual (the model) and physical (Capsule A1305). With respect to how the capsule (as a fragment of the tower) is a stand-in for the tower itself in the exhibition, Kotsioris remarked that “the practice of keeping a fragment of a building as a form of preservation within the museum context is largely owed to art history”. And this exhibition isn’t the first time a museum has used a fragment to convey the essence of a demolished building.

One example is Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens housing project in London, which was also completed in 1972. The Smithsons taught at the Architectural Association in London, and they were respected theorists who first used the term ‘new brutalism’ to describe a kind of architecture rooted in austerity, formal clarity and a respect for materials. Robin Hood Gardens was a product of this philosophy: a pair of long precast concrete social housing blocks. The project incentivised community-building through its ‘streets in the sky’: extra-wide shared balconies that ran the entire length of a housing block. But the tower was condemned for demolition in 2017 as its mismanaged structure fell apart, and certain hallways witnessed high incidences of crime.

Earlier this year, the newly opened V&A East Storehouse—designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro—in London, exhibited a detached two-storey section of the housing complex’s façade, complete with portions of its streets in the sky. Seven years earlier, the façade was featured at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale in an exhibition titled Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse. The current V&A East display features a panoramic film, resident testimonials and other materials about the building’s history. Even with all this, there’s a limit to this fragment’s capacity to convey the essence of the whole. The façade section lacks autonomy. It was never meant to be detached. It represents the essence of the prefabricated system it’s a part of. At best, the two-storey section is a reductive representation of Robin Hood Gardens, which was more than just a façade system.

In 1963, the Temple of Dendur—a 2,000-year-old Nubian structure—was dismantled and moved to protect it from being submerged during the construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt. According to architectural historian Lucia Allais, this was a period of modern history, where there was “a dramatic rise in the political power of preservationists, coincident with the global shift from conserving individual monuments to preserving entire environments”. Consequently, the reassembled temple now stands at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. While its superstructure is largely intact, the temple’s crumbling columns and graffiti-covered walls provide evidence of its lived history (although a glass box in Central Park isn’t really an authentic context). Over a decade later, in 1976, the lobby of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mayan Revival-style Imperial Hotel in Tokyo was salvaged and reconstructed at the Museum Meiji-mura in Nagoya, Japan, after the original building’s demolition in 1968. While this is more than just a ‘period room’, it falls short of an entire environment. In a more recent example, the 9/11 Museum in New York hosts salvaged pieces of the steel framing from Minoru Yamasaki’s Twin Towers. Again, while they’re close to their original context, these fragments don’t represent the towers themselves; and that was never the intent. Instead, their grotesquely distorted forms—forcibly and arbitrarily severed—memorialise the Twin Towers’ darkest day.

In each of these examples, there’s an attempt to convey a building’s form and its history through a fragment: either a reconstructed section, a minor structural element or the majority of the salvaged structure. However, most of these fragments either lacked autonomy or couldn't be cleanly or fully severed from the whole. A curator or a preservationist had to step in and identify where the fragment needed to be cut off. The only exception is the Nakagin Tower. In this case, the architect was the one who involuntarily made the choice. “What is unique about it is that the capsule itself was a full unit. Nothing had to be cut off or chopped or violently separated. And it was an object that was designed to travel”, said Kotsioris. “Of course, one capsule by itself cannot tell the story of the entire building. That's why we built this whole exhibition around it. But what’s amazing is that as a unit, it is the complete unit.” The wholeness of this fragment, and the essence of the original building, are steeped in a single idea: Kurokawa’s capsule architecture.

Kurokawa completed a few other capsule buildings after the Nakagin Tower, such as the Capsule House K (as a personal residence), and the Sony Tower, which was built in 1976 and demolished 30 years later. But he also continued to toy with ideas for capsule architecture projects throughout his lifetime. A few metabolic cycles later, in 1979, he completed the world’s first capsule hotel in Osaka. While its design resembled the Nakagin Tower, the square footage, structural frame and function were different. Capsule hotels have since proliferated beyond Japan to tourist havens all across the world. They’ve kept capsule architecture relevant even after the deaths of the Nakagin Capsule Tower and its creator.

Kotsioris remarked that the Nakagin Tower was often cited as a “failed utopian experiment”, in part because it was demolished, like Robin Hood Gardens. But even if Kurokawa’s vision didn’t go entirely as planned, the Nakagin Tower endured for nearly half a century. In that time, it bore witness to hundreds of lived experiences and became one of the most photographed and studied works of architecture in the world. The tower’s remaining fragments (both physical and digital) stand as a testament to these lived experiences. Dispersed across art institutions worldwide, they’re metabolising in ways that Kurokawa might not have imagined. However, Kurokawa and his colleagues weren’t the only prime movers in the tower’s unique story. In fact, the Nakagin Capsule Tower owes its afterlife to the people who cared for it and called it home. Lived experience isn’t at the mercy of the wrecking ball. It gives architecture meaning throughout a building’s birth, life, death and afterlife. As the critic and author Alex Ross wrote, “No house can be greater than the life that is lived inside it.” The kind of evolution and metabolic preservation that the tower has been witness to can also rewrite traces of the past. In the Nakagin Capsule Tower’s afterlife, can its remaining fragments then preserve the essence of its many lives and their messy, discordant complexity? Or will they become empty pages that allow others to editorialise the tower’s history?

‘The Many Lives of Nakagin Capsule Tower’ is on view until July 12, 2026, at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Jerry Elengical | Published on : Oct 08, 2025

What do you think?