WaterAid Garden by Tom Massey and Je Ahn inspires people to be ‘more water-wise’

by Akash SinghJul 26, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by STIRworldPublished on : Jul 19, 2024

You step out of the Underground station at South Kensington and the year is 3.5 billion BC. Flanking you are two soaring scarps of rock, and under your feet is a stone track leading you gently upwards. Slightly further ahead, rising above the grey, you can make out the leafy fronds of tree branches. You’re meant to be at the Natural History Museum, and yet, in a newly reminiscent way, you are. Reassuringly, the year is 2024 and you have just come through the entrance to the newly redone gardens of the Museum.

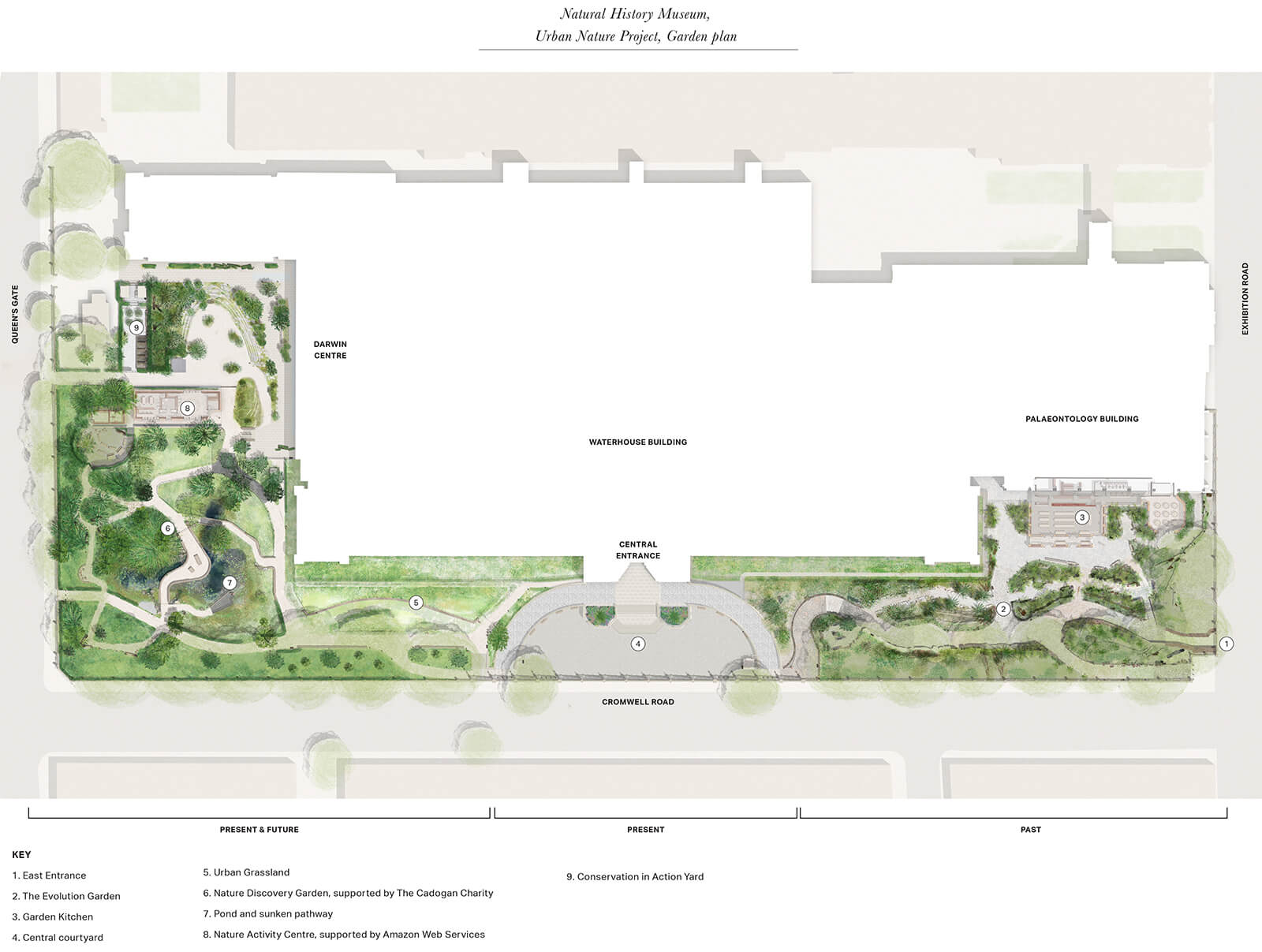

Now open to the public, this highly-anticipated, five-acre urban nature project at the Natural History Museum was undertaken by the London-based architecture firm Feilden Fowles and landscape architects J & L Gibbons. Using carefully placed architectural interventions and thoughtful landscape design, the project involved transforming the Museum’s underused frontal gardens into a more accessibly designed, welcoming and biologically diverse place. As part of the revamp, the public can now indulge in and enjoy two newly defined gardens—the Evolution Garden and the Nature Discovery Garden—and a brand-new building, the Nature Activity Centre supported by Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Functioning as a vibrant dimension within the Museum's overall scheme, the frontal gardens become a living exhibit outside institutional walls. This is best exemplified by the new Evolution Garden, beginning at the subway entrance and stretching towards the Museum proper. Its primary aim, alongside welcoming the annual 5.5 million visitors into the space, is to tell the story of 3.5 billion years of natural history and planetary evolution and resilience. Supported by the Evolution Education Trust, an immersive, chronological timeline of information is installed along the pathway, unfurling as visitors traverse it.

Lining the timeline path on both sides are stones and lushly planted areas of flora, all accurately aligned with the historical period marked by the timeline at any given section. For example, Lewisian gneiss from the northwestern part of Scotland, dating back millions of years, can be found towards the start of the timeline. Even the pebbles in the gravel infill align with the chronology. Neil Davidson, Landscape Architect and Partner at J&L Gibbons, explains how the barren rock garden at the very eastern edge of the site—seemingly bland and devoid of wildlife—corroborates with the timeline too. “There was no animal or human life to be seen during this time, and this space reflects that.”

Dotted amongst the landscape surrounding the Evolution Garden are dozens of interpretative panels showcasing facts on ancient reptiles, birds and mammals. Set at eye level and designed for children, these byte-size chunks of information aim to further engage young people and excite curiosity.

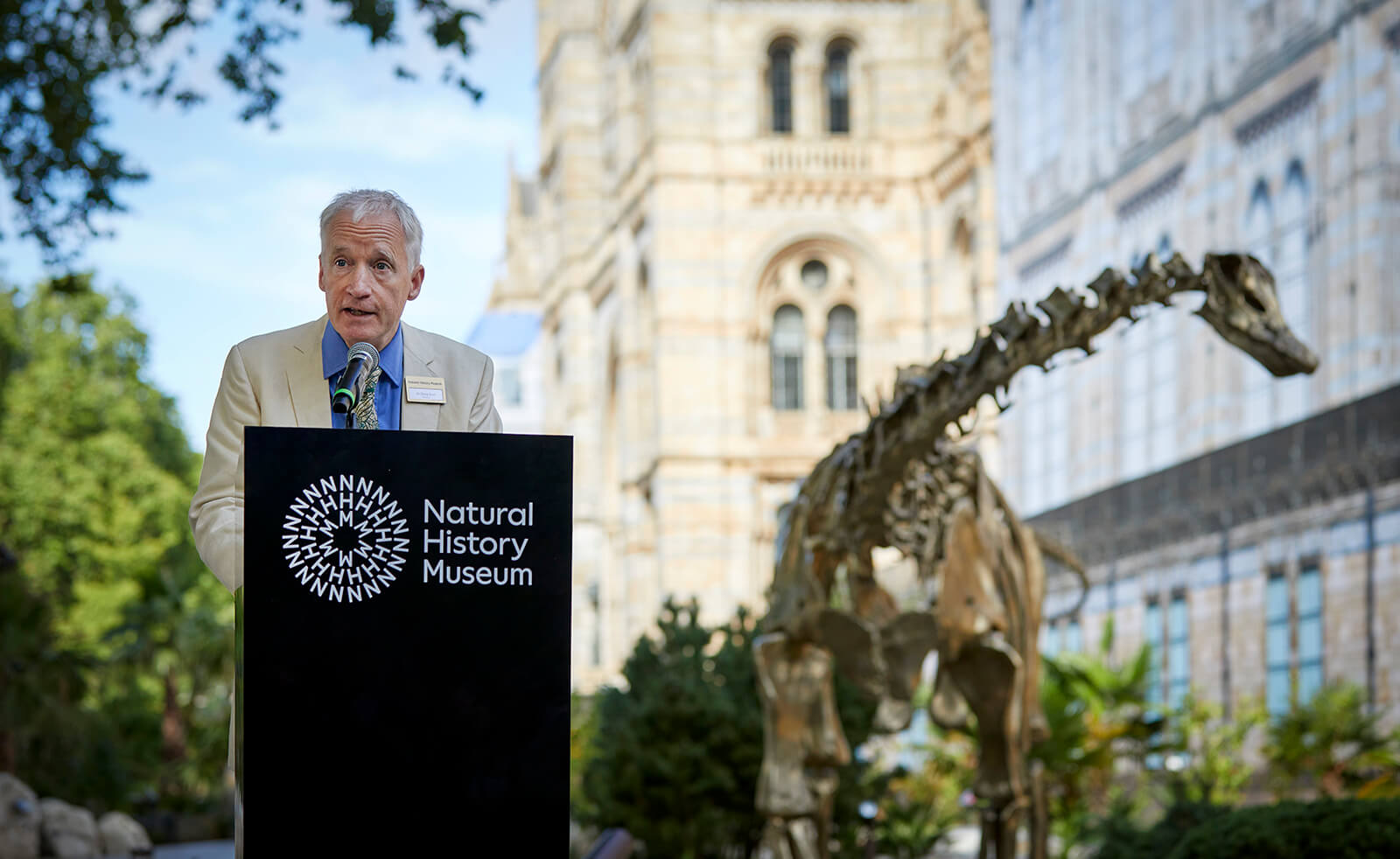

As the pathway continues, the familiar polychromatic volumes of Alfred Waterhouse’s Romanesque-and-Gothic-revival, intended as a “cathedral to nature”, emerge. But something unforeseen comes into view along this walk: a dark and spiny creature silhouetted against the façade. Revealed at the opening of the gardens to be called Fern, this resident Diplodocus is a brand-new replica of the famous Diplodocus carnegii and is cast in bronze. Sponsored by the Kusama Trust, Fern comes to life through the collaborative effort between Spanish conservationists Factum Arte and London-based engineering design consultancy Structure Workshop. It has been coined the world’s first post-tensioned bronze dinosaur and features no intermediate supports – even its long, spindly tail hangs freely suspended. A stellar fusion of engineering, craftsmanship and artistry, Fern is a valuable addition to the Museum’s collection and adds to the gardens’ allure and glory.

The Nature Discovery Garden, supported by the Cadogan Charity and the Evolution Garden, sits beyond Fern towards the West of the site. At 25 years old, much of the previous Wildlife Garden felt worn and tired. Today, however, this reimagined green space combines pre-existing elements such as patches of woodland and wildflower beds with newer additions, including a pair of large ponds. Sunken and winding between the two ponds, an accessible pathway provides access to the various newts, frogs, ducks and dragonflies that call the site home.

Accompanying this open space is a new learning and activity centre, dubbed the Nature Activity Centre supported by Amazon Web Services (AWS). It functions as a purpose-built space for learning about nature and combines facilities for scientific research, a training space for urban ecologists and a classroom for school workshops.

Each room in the single-storey structure is perforated by glazing to ensure that no interior space is without visual access to the exterior natural landscape. Feilden Fowles appears to draw heavily from Japanese architecture, boasting not only an excess of timber but also deeply overhanging eaves. On the northern side of the building, the roofline falls so low that it is almost head-height. Inside the building, the joinery of the chairs and tables (also in wood) is meticulously executed. Coupled with the warmth from the timber throughout, these design and architectural features render the new Nature Activity Centre supported by AWS a gem within the landscape. Not only is the building amicably juxtaposed against the abundant encircling greenery, but its human scale brings the institution of the museum down to a much more accessible and welcoming level.

The project is replete with similar examples of the acute attention to detail across both the outdoor areas and the interior architectural spaces that make these new interventions at the Natural History Museum so magical. Some others, to name a few, include the new outside handwashing sink trough in the Nature Discovery Garden, and the handmade backsplash tiles inside the learning space that were made using leaves from other London-based community gardens. Lastly, the raw stone footpath was left un-processed intentionally to allow for wet footprints and rainwater to alter its colour and tone.

Indeed, almost every surface throughout the gardens has a tactile quality. Inside the Museum, most artefacts and displays aren’t allowed to be touched. However, outside in the Gardens, touch is a sensory experience that is actively welcomed. A particularly fun interactive element involves another bronze Diplodocus skull that lies on a rock next to Fern. Placed at waist height and within arm’s reach, the Museum encourages visitors of all ages to touch and interact with its bony head and teeth.

Visual domination apart, Fern is a major awe-inspiring detail in the space. On seeing the dinosaur come to life in situ after many years of hard work, Peter Laidler, the Founding Director of Structure Workshop, commented: “It’s so fantastic to see Fern finally in the garden, but the thing I keep coming back to—and this came out when we were assembling the piece in the workshop with Factum Arte—is that this animal re-ignites the child in you. Putting it all together was akin to building a toy model as a child. It evoked and continues to evoke a lot of excitement.”

Part of the initial inspiration for the entire garden redevelopment programme sprung from an institution-wide concern about the climate crisis and planetary emergency facing us. “From a diesel-free site to no waste being sent to landfill, to harvesting rainwater for the plants, creating a sustainable design that worked with the landscape and taking an ambitious approach to sustainable construction was at the very heart of the redevelopment project,” an official release from the Museum states. The existing Wildlife Garden and pond, towards the West of the site, were also extended to double the area of native habitats within the grounds and better support biodiversity.

Sustainability, similarly, underpins the concept of the Evolution Garden as well. Telling the story of the natural world, from the beginning of time to the present day, implies teaching visitors about the fascinating nuances of the planet around us and how far we have come as an interrelated species among others on the planet. On the significance of this, Director of Estates, Projects and Masterplanning Keith Jennings states that “inspiring young people to become advocates for the planet through learning and, for them, therefore, to make changes,” lies at the heart of the scheme.

Another important facet of the design concept came from a wish to establish a free and accessible space for visitors to immediately and explicitly connect with nature. Within the context of Central London’s dense urban fabric, such access feels increasingly rare.

Ultimately, however, the most striking message enunciated by this space is that nothing on this planet, or in this life, stays the same. Not only is this articulated by the Evolution Garden’s winding timeline, but the myriad other features in the landscape also become living testaments of this thought. Flora has and forever will be in constant flux: wildflowers will bloom, algae will cover stones and grow in the pond, and trees will stretch tall, while also meeting their eventual end. With exposure to the elements and persistent public use, the gardens’ man-made details are similarly subject to change – picture-smoothed benches, chipped paint and worn-down handrails. Even Fern will transform. Purposely left unpatinated, London’s rain (and pollution) will eventually turn its bronze bones a hue of green and red. And yet, there is something quite poetic about a space that so explicitly conveys a notion so fundamental—something that underpins the basal essence of the natural world—renewal. In this space, the processes of the world might suddenly make sense. Nothing stays the same and that is alright. It might even be something to celebrate, and the gardens carry this emancipatory notion throughout.

The new gardens at the Natural History Museum will be open to the public from July 18, 2024 onwards. General admission remains free.

Name: New Gardens at the Natural History Museum

Location: Natural History Museum, London

Architects: Feilden Fowles

Landscape architects: J & L Gibbons

Construction: Walter Lilly

Sponsors: Amazon Web Services, The National Lottery Heritage Fund, Evolution Education Trust, The Cadogan Charity, Garfield Weston Foundation, Kusama Trust, the Wolfson Foundation, Charles Wilson and Rowena Olegario, Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, Clore Duffield Foundation, Workman LLP and Accenture

(Text by Sophie Hosking, intern at STIR)

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by STIRworld | Published on : Jul 19, 2024

What do you think?