Iannuzzi Studio designs the Briarcliff house as an 'unplottable' residence in Michigan

by Zohra KhanSep 15, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Akash SinghPublished on : Mar 22, 2025

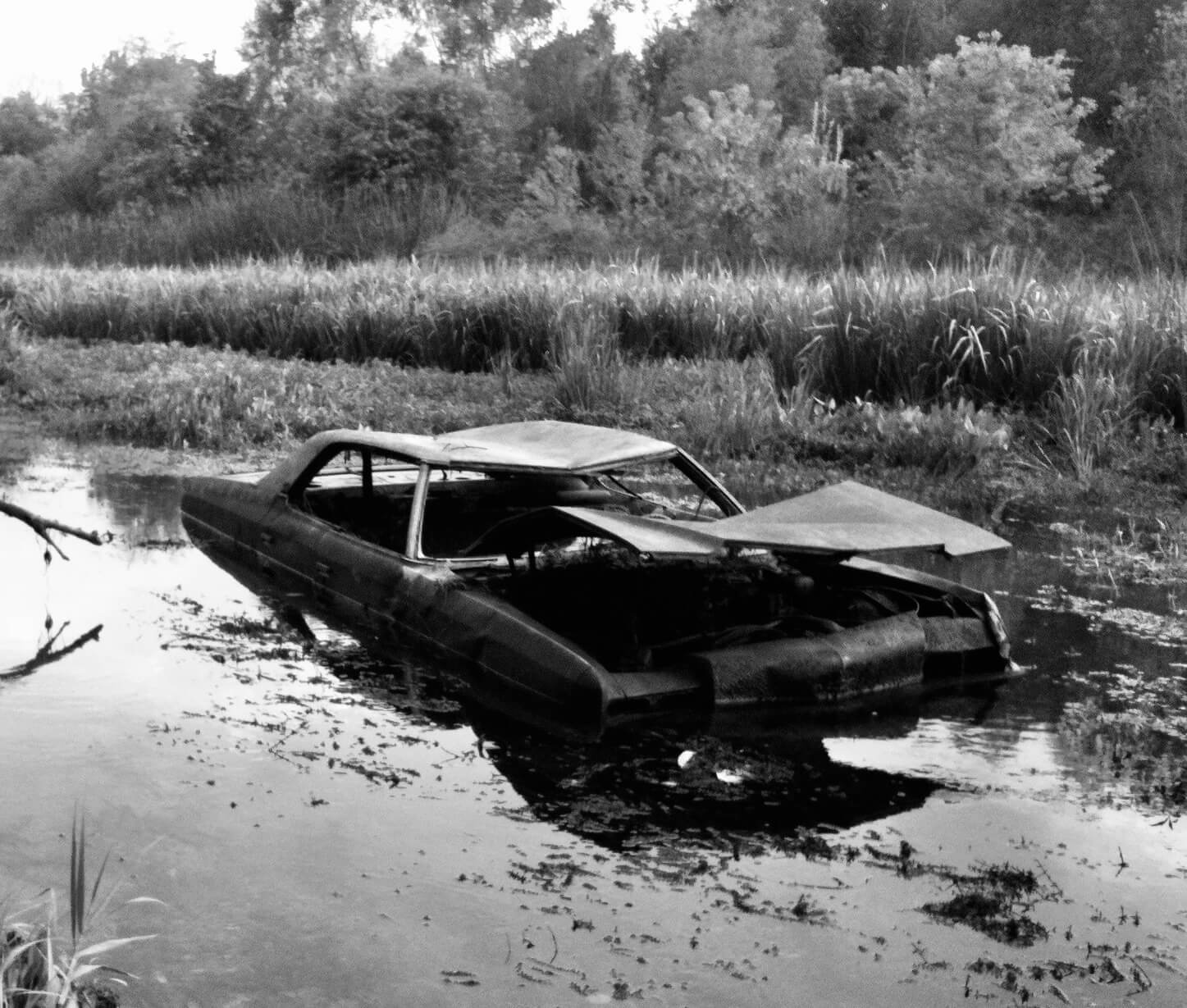

Most post-apocalyptic fiction often renders a dismal portrait of our urbanscapes, comprising decaying concrete pillars, roots emerging out of cracked pavements, overgrown foliage obscuring the proclamations of gigantic billboards, humanity’s ‘legacy’ withering away and erstwhile prime real estate being reclaimed by the wild. However, come to think of it, such images aren’t limited to our imaginations of the future. Desolate infrastructure being reclaimed by nature is a common enough sight in liminal pieces of land like abandoned lots, obsolete infrastructure or land embroiled in legal issues. With time, nature is bound to ultimately take over is what these places and spaces seem to convey. With the ephemerality and futility of our ‘control’ over nature becoming more and more apparent, as natural disasters intensify and ecosystems dwindle with each passing day, how do we tread into the future? What does the future of humanity—and, by cautious extension, that of Earth—look like? One possible image broached above, of a wilderness taking over the ruins of our hubris, begs further questions: Will humans still be in control in the future? Alternatively, what kind of future lies in relinquishing control to other elements, of letting go of the desire to control the natural?

This unorthodox perspective—that the path to biophilic ecotopias lies not in creating engineered natural landscapes that blend with urban infrastructure but in allowing, even facilitating, nature to take over—is explored in Christopher Brown’s The Natural History of Empty Lots. The book presents Brown’s encounters with what he calls urban wastelands: urban creeks and floodplains, empty lots, rights-of-way, industrial parks, storm sewers, traffic islands, medians, brownfields and rare pockets of land that have somehow escaped the onslaught of development, along with their histories, present ecological richness and uncertain futures. Brown presents readers with personal field notes from these “urban edge lands, back alleys and other wild places” to argue for a personally held belief that the redemption of our habitats lies in embracing the wilderness. This fascination with the urban wild is apparent in the rich text.

Divided into three parts—Finding the Wild City, Rewilding Domestic Life and Rewilding the Future—Brown’s narrative expands into the natural histories of the various species he encounters, their resilience and vulnerabilities and the overarching effects of the exclusive ownership of land on ecologies, which is a colonial residue. In the text, Brown reveals the resourcefulness of the wildlife he encounters from their interactions with human life. How cardinals adapt to building better nests using waste from human products, foxes hiding and hunting in the overgrown parts of large plots and coyotes occupying abandoned buildings, for instance, all form part of the narrative.

He highlights the sightings of rare indigenous plants such as the Shame Vine, Indian Blanket and the Mexican Hat in the unlikeliest places. Throughout, readers follow Brown in and around the neighbourhoods he’s lived in, interweaving these with stories of the process of building a private residence for him and his family: Edgeland House by American architects Bercy Chen Studio, featured on the book’s cover. Brown uses his observations of the blurred edges between urban landscapes and the wild in the sites he traverses, probing readers to think about how they might intersect with the greater aspects of our collective urban experiences and behaviours. While the context he focuses on is specific—neighbourhoods in Austin in Texas, USA—his ideas and beliefs about the natural world hold universal relevance.

As we continue expanding urban landscapes to make way for growing populations, and as natural landscapes dwindle in the face of incessant concretisation of the terrain, Brown’s stories of nature surviving in derelict lots and unused interstitial spaces offer a glimpse or a window into an alternative future. While this vision is near nostalgic, prioritising the polarity between the ruin of development and the bucolic nature of the pastoral landscape, Brown brings up pertinent points about the loss of species in our current age and humanity’s pervasive role in this loss. This combination of the climate crisis and capitalist exploitation, Brown tells us, has led to “a world that has lost 69 per cent of its wildlife population since [his] sixth birthday”.

As a counter, the perspectives offered in the book, oscillating between ideas of ownership and those of reclamation, challenge a common notion that nature and humanity need to be separated since that separation allows us to overlook our intrusive ways of living, which often deprives other life of its rudimentary right to exist. He highlights, “Bringing back as much of the biodiverse life we have destroyed as we can—and saving the pockets that have somehow evaded our machines—is self-evidently worthy. But on an overheated planet marred by the sprawl of eight billion humans, the path to ecological health will take a lot more than islands of conservation.”

Brown’s belief in blurred edges also manifests in the way he describes the process of building his house. His keenness on retaining the scarred memory of the lot’s industrial past while also invigorating the house with a sense of wildness reflects his innate desire to allow ‘Indigenous’ greens and nature to flourish where possible. Brown further describes the challenges associated with erecting an edifice of this nature and maintaining its re-wilding, saying, “Keeping it that way requires constant vigilance. The invasive species always appear, and to try to keep them completely at bay, especially when working with an urban plot surrounded by properties that are not so maintained, is a Sisyphean undertaking.” The role of ‘invasive species’ in this architectural metamorphosis is particularly interesting and noteworthy, especially in its perpetuation of an associated cycle of rebirth and redoing, as opposed to a perceived termination when the invasive species in question are us, humans.

The book concludes with accounts of climatic disasters from recent history and the American author’s personal experience with them. He writes, “The winter storm of 2021, which left much of Texas in the cold and dark that week, is just one of the climate-related crises we've experienced here in the past decade. We've seen floods that came over our back fence, a hurricane that submerged Houston, wildfires that come dangerously close to town and summer heat waves that break the power grid from the other direction.” He underscores the urgency of the text’s message by lending a personal experience to help frame the larger picture.

In another recent book, Feral Atlas, Anna Tsing introduces the concept of ‘ferality’ to understand how wildlife adjusts to contexts forever altered by human intervention. Through the introduction of invasive species in foreign lands or the destruction of native species, the ‘patchy Anthropocene’—as Tsing refers to the patches that reveal the interconnectedness of humans and nature—shows us a way to think about how nature may thrive, while still reiterating the profound shift in ecological networks and the effect this has not only on the terrain but also on humans. It is this idea that Brown seems so intent on highlighting in his book, asking the reader to look closely at the landscapes—as opposed to the land—that they inhabit.

Brown’s ideas and narratives leave significant food for thought for architects, urban planners and designers at large. His narratives help us look at urban spaces through the eyes of wild creatures and how they inhabit these spaces. The idea of making space for birds and creatures in built architecture isn’t entirely novel—like in the Mourning Dovecote and Sinfonia Verde—but it has generally been limited to being rare features in architectural projects, not as a rather collective sociocultural undertaking with a hint to prompt ecological revival. If Brown’s ideas are to be further examined, ‘making space’ is no longer a requisite. As designers, the more relevant questions to ask become—how can we build less? How can we contribute to ecological repair while doing that? And essentially, following a regenerative respite from ‘invasive species’, how do we let go of control and let nature take its course?

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Akash Singh | Published on : Mar 22, 2025

What do you think?