To the Moon, Mars, and beyond: Innovative space architecture projects from 2021

by Jerry ElengicalDec 12, 2021

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Apr 18, 2024

The general sense you get while reading Kelly and Zach Weinersmith’s recent book on the practicalities of and unanswered questions about space settlements is that, as they write, “space is terrible. All of it.” So, why has most of humanity put faith in the idea that we can move there, possibly soon? Why do advocates for space settlement imagine it to be a utopia with a vast cache of resources, free from the threats of conflict or the climate emergency, a terra nullius that will unite humanity in its quest for the stars? Often, this argument has stemmed from the anxiety that the human race is doomed if we stick to Earth; a planet ravaged by our ancestors, facing certain ruin.

Humanity must not stagnate confined to a dying planet–space enthusiasts such as SpaceX founder Elon Musk cry–when there are unexplored frontiers outside Earth to be ravaged in turn. So to infinity and beyond it is! But, will it really be that simple? As it turns out, the Weinersmiths don’t think so. As they elaborate on in the book, advocates for space exploration and colonisation are often so blinded by shiny technology and its promises that very little attention is paid to questions about reproduction, ecology, economics, sociology, and perhaps most importantly, warfare. Moreover, of the many things we know about space, there are still a lot of things we don’t know like how radiation will affect us long-term. As the writers reiterate, these are things we should probably figure out before we start building facilities for over 100 people on the Moon. Or Mars. Or maybe Venus? As self-proclaimed space geeks, they confess that they have a vested interest in the subject. But they are also sceptical, using their research as a “sociological roadmap” to inject some realism into the current discourse on the prospects of space habitats.

As someone who pictures works such as Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles or Joss Whedon’s Firefly or James SA Corey’s The Expanse series when talking about inhabiting space, I share their scepticism. The worlds these works and many others have built underscore the fact that while fictional, colonialism and border mentality seem to be everywhere, even in space. You can’t escape it. That is to say, as they write, “[space] wouldn’t stop nations from having religious differences, bad leaders or suspicion about rivals.” The third part of the book dwells on these nuances, lucidly explaining ideas of space commons and existing space treaties. The first two parts, of more interest to settlement designers and enthusiasts like myself, go into specific details about the functioning of spaceships and how they keep us alive; and what might be the best planet to settle on. The most incredible aspect is how much attention the book pays to every detail of habitat design, from how to protect our potential homes from radiation to creating a self-sustaining ‘paradise’. So, it was a pleasant surprise to stumble on it in a local bookshop while I was working on an article that talked about a proposal for 3D printing homes on the Moon.

Wanting to know more about their research and get a realistic opinion on the feasibility of the speculative designs by architects such as BIG or SOM for agencies such as NASA or the European Space Agency, I spoke to Kelly Weinersmith, one of the authors of the book. In the interview, we talked about how we might deal with excrement in outer space, will we or our robots be able to fight radiation when we’re out there, and space babies. Below is an excerpt of the conversation.

Mrinmayee Bhoot: If there’s one thing I loved about the book was how well-researched it was. And there were quite a few stories that seemed too farfetched to be true. I’d love to know the weirdest thing that you discovered in your research.

Kelly Weinersmith: The proposals for settling Venus and Mercury, to be honest. I feel bad saying that because after the book came out, a guy who runs the Humans to Venus organisation, who thinks this is totally a viable good plan, reached out to us and we've been sort of in contact since. Maybe let's focus on Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, super hot on one side and cold on the dark side because it has no atmosphere to hold any heat. But if you're right at the spot where day is becoming night, the temperature is sort of mild, so people have proposed putting a habitat on wheels and just moving your entire civilisation every day. That just sounds like a miserable way to live, and if your wheels break, you’re going to burn to carbon dust!

Mrinmayee: Perhaps we could talk about some space designs that claim to be more practical. There was a proposal recently by Interstellar Lab for a project called EBIOS that claimed to be an autonomous and bio-regenerative terrestrial village. Do you think that could provide a viable prototype for settling say, Mars?

Kelly: I was excited to see that the EBIOS project is starting to work on closed loop ecologies. Because I think that is something that we don't have anywhere near enough data on. So I'd love to see these small experiments being run over and over and over again, so we can figure out things like, how many wheat plants do you need to scrub the carbon dioxide produced by four people or something like that? And it's going to take a while to get that information. But what I was a little worried about is that it looks like the EBIOS project has used glass in their façade design.

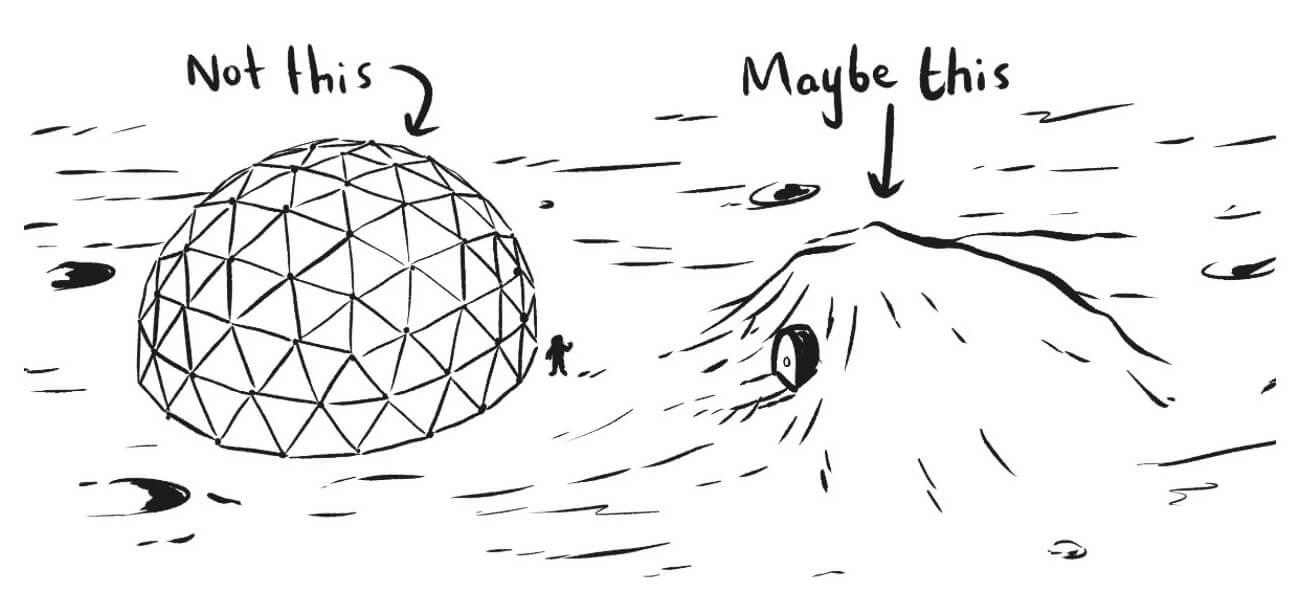

That’s a problem because we don’t understand space radiation very well. So, the astronauts on the International Space Station are protected from lots of space radiation by the magnetosphere, and Mars does not have a strong magnetosphere. Plus, it has 1 per cent of the Earth's atmosphere, so space radiation is going to be hitting the ground much more so than it does on Earth. So if you've got a glass dome that you're living under while in space, that could be a problem. There’s this great architecture book written by Brent Sherwood, all about architecture and space. And he said that anyone living in glass habitats is going to be baked by the radiation. So that's just not going to happen, despite how beautiful it is.

I do love the idea of these glass domes, but if you die of cancer, you know, six months in, it's not a good trade off. I wouldn't want to die of cancer in six months on Mars, away from oncologists on Earth. That just sounds unpleasant.

Mrinmayee: I think the glass façade also has a lot to do with aesthetics, but you make a very good point. I also think when we read about proposals for space architecture; architects often mention fancy amenities like greenhouses, recreational spaces, or even 3D printing with lunar soil as a sustainable design solution.

What they don’t talk about and I believe you mention in your book, is where the food will come from, or electricity. There seems to be a reluctance to focus on research on better food or renewable energy resources. Which closed loop systems like EBIOS might address.

But let’s talk a bit more about 3D printing technology. Do you think we can 3D print homes on the Moon or Mars anytime soon?

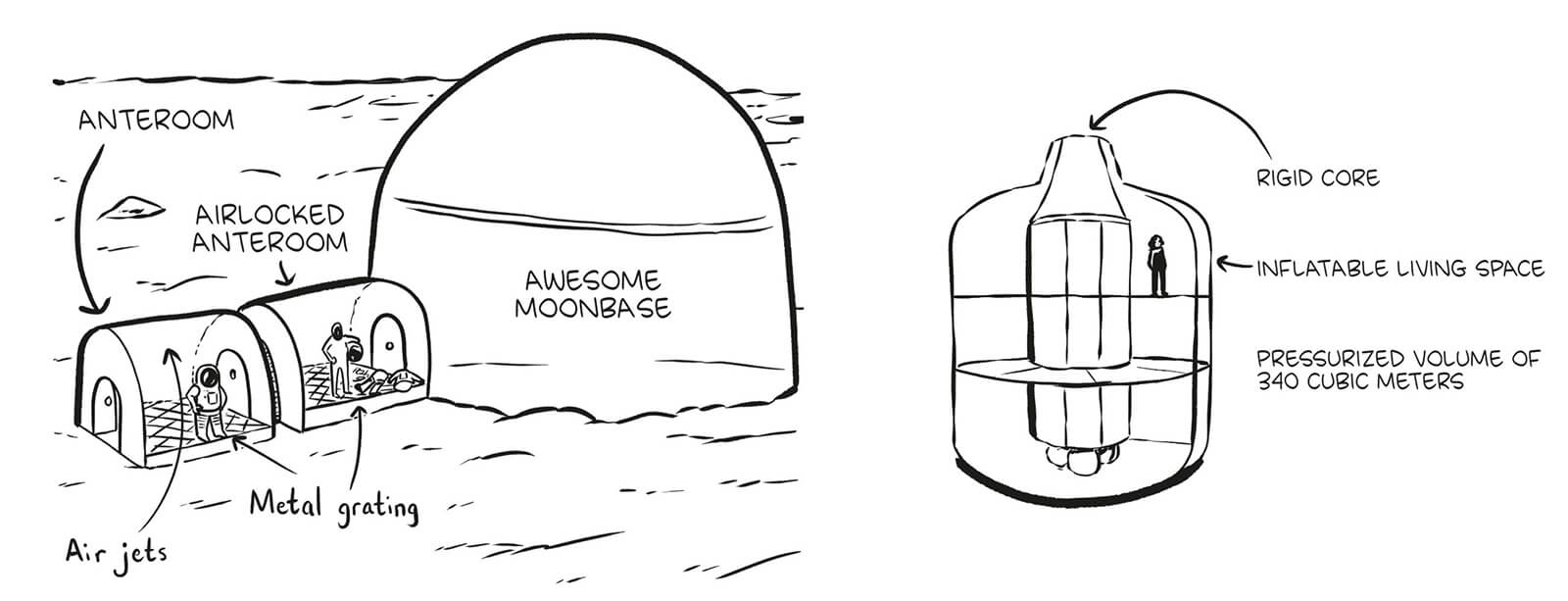

Kelly: Not anytime soon. Haym Benaroya has written some great books about lunar architecture and the way he thinks it's going to work is first we're going to send habitats that are essentially cylinders that we've made on Earth, like modules from the International Space Station. We'll send those and we'll start by living and having research stations in those. Stage two will be to make prefabricated structures that you can inflate when you get to your destination, something that you can blow up and then rigidise. So you get a little bit more space than the cylinder, but you still need to fit all of your habitat inside of a rocket that is going to the moon, for example. The stage after that would be in situ resource utilisation.

Something like 3D printing using the regolith that you find on the Moon or Mars. But that's going to be really hard because regolith isn't like the dirt you find on Earth. It's a lot more jagged. It is also electrically charged so it clings to any surface. I was reading an article that said that when you try to get it through equipment, it's expected it might gum up and get a little bit more viscous and hard to work with. So I would imagine that the nozzle on your 3D printer is going to get clogged up quite often. Which means you're going to need to replace the equipment regularly because the abrasiveness of regolith is going to wear it out.

And you need to pressurise your habitat. So I can imagine 3D printing might work outside of your habitat. Maybe that would be an easier way to bury your habitat in regolith. So, if a rocket lands nearby, whereas before the exhaust could blow your radiation shielding away; now, if you've 3D printed it and cemented it together, it would be more likely to stay in place.

But apart from that, I think we're a long way from being able to create pressurised habitats out of materials that you find on Mars or the Moon. So I would not expect those to be our early habitat designs. Also, it is so expensive to send stuff to the Moon or Mars. If we could eventually just send a printer and use materials from there, that would be ideal, but we're a while away from that.

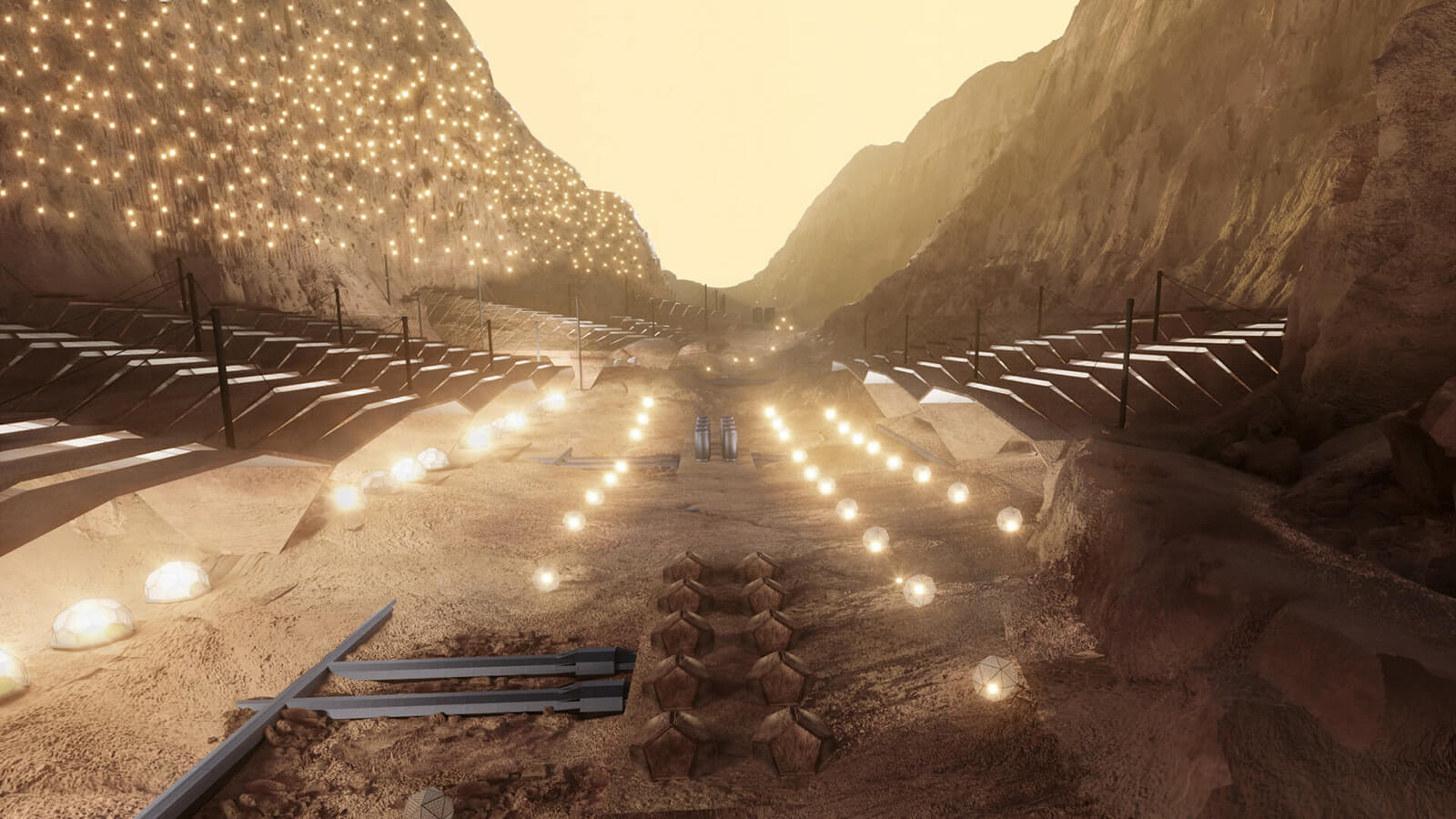

Kelly: Can I ask you a question? I was excited when I read about ABIBOO Studio’s design for Mars' first planned city Nüwa. I thought that was a very cool way to think about how to protect settlements from radiation. Maybe you can tell me this because I'm certainly no architecture expert. Building into the side of a mountain sounds like a difficult thing, especially in a harsh environment we don't have a lot of experience with. What do you think about the feasibility of that project?

Mrinmayee: Building into the side of a mountain is very cool, but given the fact that there'll be robots doing this and they'll be dealing with soil that's definitely very hard to work with, they might end up hitting areas where they will not be able to build. So it'll be very difficult for the pod to anchor onto the side of the mountain. Because, if it's not structurally sound, it may just topple off. That’s a very real danger.

Kelly: Yeah, that was my sense also, but I don't know too much about how to build into the sides of mountains. It's a cool idea, but then I remember reading about NASA's Insight Project which was launched in 2018 to try to drill into and collect data on the Martian surface. And we got down something like a few centimetres before we hit a hard spot. It’s amazing to me how much we've managed to get robots to do on Mars already, but it's still clearly a really hard environment to operate in that we don't know a lot about. So if we're having robots build these habitats, it does sound difficult to execute.

Mrinmayee: I agree. And again you mention this in your book, there’s a real danger robots or other mechanisms might malfunction because of radiation and regolith. So that might present an issue as well?

Kelly: Oof yes! What do you do if you have half a 3D printed home? I don't know, these are really hard problems like you said. So radiation, bad for humans, also bad for our robots, and there are a couple stories that we had in the book. I think in one of them, there's a sensor that went off saying there was ammonia. And that was probably a false alarm set off by radiation, and then there was that radiation sensor that was orbiting Mars that got hit by solar flare and died from an overdose of radiation.

So if you leave for a trip to Mars and you're expecting that the robots you sent ahead of time to have your habitat completed by the time you get there, it’s probable you could be in a lot of trouble. And again, I think things are going to wear down because of the regolith. I think there are a lot of experiments that we need to do ahead of time, many times to make sure that we've got reliable stuff set up. It's going to be a difficult task. Almost certainly not impossible, but not something we should expect will work perfectly the first time we send it up there.

The conversation ended with as much scepticism about the future of space settlement as it began. Space is really cool, and a lot of the proposals address real issues like in situ resource utilisation or energy production. But we still need to carry out a lot of experiments before we can have actual cities and communities living, and more importantly, prospering in the great beyond. Probably, we won’t be there by 2029 or even 2050. For now, as the book says, “An Earth with climate change and nuclear war and, like, zombies and werewolves is still a way better place than Mars.”

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Apr 18, 2024

What do you think?