Ukrainian Modernism charts a nation’s fractured architectural history

by Dhwani ShanghviAug 21, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Nov 03, 2023

While visitors to Uzbekistan, world-renowned for its ancient mausoleums, mosques, and madrasas that ennoble ancient cities along the Silk Road, most famously, Bukhara and Samarkand, may not expect to encounter traces of modernity that is exactly what they will stumble upon while exploring the country’s capital, Tashkent—colossal sculptural concrete buildings, remarkable remnants of the late Soviet period, sort of fragments and echoes of futuristic Brasilia in Central Asia. Unlike the omnipresent, practically featureless mass-produced housing blocks that characterise Soviet cities, these public structures—from circuses, markets, theatres, museums, cinemas, hotels, and stadiums to airports, sanatoriums, science institutes, department stores, restaurants, and metro stations—display a strong architectural character, the built embodiment of the long crumbled Soviet Empire. These extraordinary time-capsule objects, built over three decades, from the late 1950s to the late 1980s, in what is now 15 independent states in Eastern and Northern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Far East have since acquired their mythology, which provoked much public interest, scholarly research, and even a popular movement calling for these buildings' preservation. After all, many of them have fallen into disrepair; quite a few suffered from insensitive remodelling, and some, already, have been lost to demolition.

Where in the World is Tashkent (without a question mark) is the title of the first conference on the preservation of the Uzbek capital’s modernist architecture. The two-day event, held on October 18-19 at Tashkent’s State Museum of Arts, itself an important example of late Soviet architecture, a former Museum of the Arts of Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, completed in 1974, coincided with the opening of an extensive exhibition, Tashkent Modernism. Index, which is now on view around the museum’s four-story square atrium. The show features original archival materials, paintings, graphics, and large-scale contemporary photographs by Italian photographer Armin Linke. It is curated by Ekaterina Golovatyuk, the founder of the architectural practice, Grace in Milan. Earlier this year, the exhibit was shown at the Triennale di Milano.

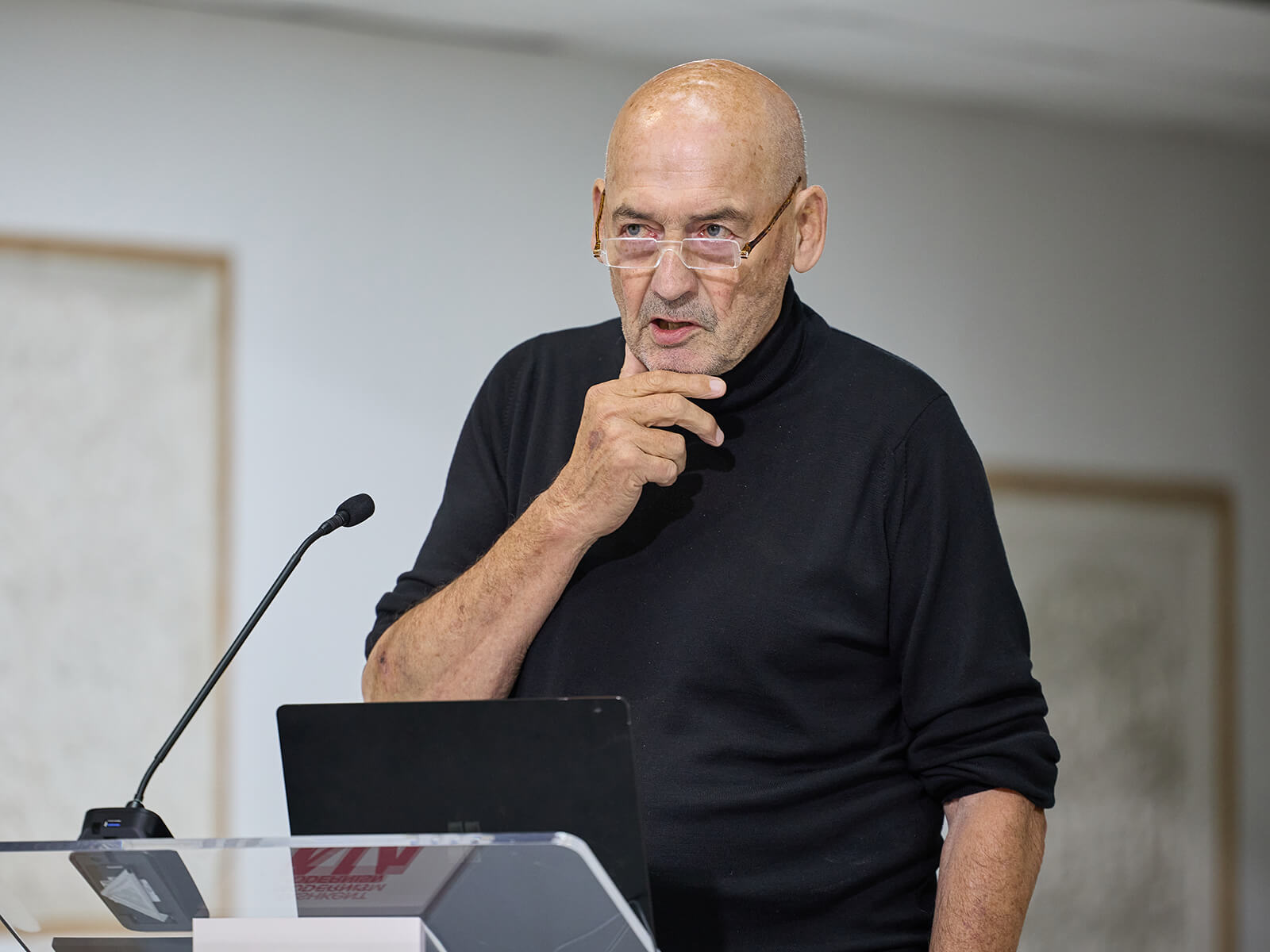

Both the conference and exhibition were organised by the Tashkent-based Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (UACDF) as part of the Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI research and preservation project to "align the Uzbek capital with other cities around the globe that significantly contributed to the modernist movement.” In addition to the discussions on the late Soviet architecture’s relevance, reimagining public spaces, and exploring the new roles of cultural institutions, the participants addressed Tashkent’s candidacy for UNESCO World Heritage status. The conference was opened by the recently appointed Mayor of Tashkent, Shavkat Umurzakov; Saida Mirziyoyeva, the head of the Communications and Information Policy Sector of the Executive Office of the Presidential Administration; and Gayane Umerova, Chairperson of the UACDF. Renowned Dutch architect and the founder of OMA, Rem Koolhaas gave the keynote lecture, A New Preservation on the creative use of preservation as a design strategy. More than a dozen speakers and several discussion groups included Gayane Umerova, Ekaterina Golovatyuk, historian Boris Chukhovich from Montreal, Milan-based preservationist Davide Del Curto, Turin Polytechnic professor Nicola Russi, British curator Shumon Basar, as well as museum directors, researchers, curators, and architects, both local and from around the world. The conference was dedicated to the memory of Jean-Louis Cohen, a Paris and New York-based architectural historian and irrefutable authority on Soviet architecture who passed away this year and who was among the key organisers of the conference.

To begin to understand the meaning and uniqueness of Soviet architecture on the world stage it has to be stated that apart from merely a decade after the foundation of the USSR in 1922 and a few years before its demise in 1991, architecture was first and foremost an ideological project. No private practice was allowed and the profession reflected the political agendas quite attentively. Stylistic preferences were not disputed, they were followed. Twice Soviet architecture changed its course 180 degrees, every time dismantling its foundations entirely by tumbling down its heroes and starting anew. According to Soviet architect and publicist, Felix Novikov (1927-2022) architecture went through three distinctive periods: Avant-garde (until 1932), Social Realism (adaptation of Classical heritage, 1932-55), and Soviet Modernism (return to Avant-garde and constructivist models). The latest lasted until the mid-1980s, followed by post-perestroika years when new buildings could be described as Post-Modernist at best, but more often than not, resulted in dicey expressions of pure kitsch.

This third period, as did the second, started from the top down, suddenly and universally. Soon after Stalin’s death in March 1953, a huge architectural competition to design a grandiose pantheon to house his body did not receive proper official attention. Then, on December 7, 1954, at the opening of the All-Union Builders Conference in the Kremlin, Khrushchev denounced Social Realism, referring to the then-practicing architects’ buildings as “over-indulgent” and “wasteful.” He even accused them of creating “monuments to themselves.” Almost a year later, on November 4, 1955, the Soviet leader signed the party-government resolution titled “About eliminating superfluities in design and construction.”

Finally, on February 25, 1956, at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR, Khrushchev denounced more than just architecture, the subject of his criticism was the personality cult of Stalin himself. Everything associated with his name had to go—any “excess.” Now architects had to work with simpler forms and fewer details, and expensive materials would be substituted with cheap ones. The profession was charged with addressing social issues, most urgently, eliminating the housing shortage, which had to be achieved economically. Contractors were given authority over architects and special committees were formed to cut every unnecessary expense. As was the case with the most talented architects of the Avant-garde period, this time the leading classicists were stripped of their honors and roles of heads of design studios. It was the youngsters who were entrusted to take the lead. They were asked “more boldly to master advanced achievements of the national and international construction industries.” In fact, some of the leading and promising young architects were allowed to travel abroad for study trips to Italy, France, and the USA. A renewed spirit of innovation infiltrated all creative spheres. It was the beginning of a short-lived period in the USSR, which has become known as the ‘Thaw.’ In 1958, Moscow hosted the Fifth Congress of the International Union of Architects.

The earliest Soviet post-war modern buildings started appearing in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They were largely inspired by the International Style, constructivism, and American mid-century modern. These buildings expressed clean lines, volume rather than mass, contrasting forms, the dynamism of asymmetry, floor-to-ceiling glass, and lots of concrete. The applied ornament was now passe. The campus of the Palace of Pioneers in Moscow’s Lenin Hills (architects: F. Novikov, I. Pokrovsky, V. Egerev, V. Kubasov, and others), a competition-winning project, was opened in 1962 personally by Khrushchev. He liked it enough to declare the complex to be the model for all Soviet architects who followed his instructions quite literally. Soon largely dull prefabricated panel construction, indifferent to the distinctive climates, environment, and cultures ‘flooded’ the vast country. Just imagine—all architecture then was exclusively modernist and almost entirely standardised. Customised works were a rarity. Most cities had none.

Critic Alexander Ryabushin wrote in his book Landmarks of Soviet Architecture 1917-1991 (Rizzoli, 1992): “In the sixties, it seemed that all multiplicity of form—regional, national, and local—had disappeared from architecture forever. Mass production in the mode of the industrial conveyor belt had flattened the city. The amount of residential space increased, but blandness was implacable. This didn’t happen just to individual cities—the architectural character of the whole country was lost.” This architecture was almost entirely derivative, insensitive, and uninspiring. Nevertheless, many architects tried their best to create works that were special despite all odds. Such unique conditions as complex terrain, unusual public function, or distinctive local culture were among the chief arguments for these passionate architects to push to elevate their innovative creations to the level of an art form. Keep in mind that so many of the Soviet modernists were recent converts who were trained as classists. Their buildings may have been simple but not simplistic.

In the meantime, Tashkent, being the largest city in Central Asia, has become a true architectural laboratory and proud vitrine of the socialist lifestyle in the region. During the war years, many factories and industrial plants were evacuated to Tashkent from the west. The city’s population doubled and reached one million. In 1959, when modernism became ubiquitous, the city master plan was updated. Among Tashkent’s earliest modernist gems was the Palace of the Arts, now Panoramic Cinema. Completed in 1964, the 2,300-seat auditorium volume was shaped as a stumpy section of a fluted Doric column surrounded by transparent linear slabs of airy foyers and hallways, a stylish stage for international film festivals and a peek into a modern, perfectly glamorous artsy atmosphere. Another distinctive structure, built the same year, was TsUM, Central Department Store, an urban three-story corner slab with extensive glazing and elegantly uplifted on slender pilotis; unfortunately, the building’s facades are now entirely lost to remodeling. Then came the devastating earthquake of April 1966.

For Tashkent, the 1966 earthquake was as destructive as the 1871 Great Fire for Chicago; both fundamentally changed these cities’ futures. Even though human lives were largely spared—the official statistics recorded eight casualties and 150 injured—nevertheless, 300,000 people were left homeless and thousands of buildings were leveled, most severely in the old town. The entire country mobilised to reconstruct Tashkent. Architects and builders from all corners of the Soviet Union came to take part in the massive rebuilding project. Many moved to the city permanently to build their professional careers here. The sheer volume of construction, compared to the pre-earthquake times, rose more than tenfold.

In the following decades, the city acquired many distinctive, even spectacular buildings. They include the Tashkent affiliate of the Central Museum of Lenin, now the State Museum of History of Uzbekistan (1970); Café Blue Domes, a beautiful assembly of open and enclosed modular bays, at once fundamentally traditional and radically modern (1970); the 17-storey Hotel Uzbekistan with its open-book main façade from top to bottom covered in labyrinthian Brise soleil system, evoking traditional Uzbek decorative sun screens called pandzhara (1974); the House of Youth with hotel, theater, clubs, and restaurants (1974); the 17-story Editors Block of the Publisher of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan topped by a huge face-like clock (1975); the 2,500-seat Circus arena, a deeply ribbed circular crown-like form (1975); the Exhibition Hall of the Union of Artists, an elegant temple-evoking slab fully surrounded by an accordion-like portico with pointed arches and ample ornamentation (1978); Palace of Friendship of the Peoples, an imposing structure reminiscent of a huge jewelry chest profusely decorated inside and out around a 4,000-seat auditorium (1981); 375-meter Television Tower with an observation deck and rotating restaurant, all shaped into a dynamic structure that recalls a giant rocket ready to take off (1981); the 17-storey Experimental Housing Block ‘Zhemchug’ (Pearl) with recreational communal courtyards and gardens arranged in five stacked three-story clusters, a vertical version of the Uzbek Mahalla which refers to a traditional neighborhood or courtyard (1985); and Chorsu Basaar under the magnificent 86-meter-diameter bright green and blue colored dome (1988). In 1977 the first nine-station section of Tashkent Metro opened. Several additional lines soon followed. Each station is resolved as a uniquely designed interior, either colonnaded or vaulted. Like in many other Soviet cities, these stations are not merely efficient and convenient; they constitute an underground necklace of grand welcoming civic spaces that instill pride in citizens. Here is how architect Alexey Dushkin who designed half a dozen metro stations that were among the earliest realised in Moscow, a direct model for stations in Tashkent, characterised the opulent Soviet metro: “Their palaces are for Pharaohs, but ours are for the people.”

The importance of the 1966 earthquake is such that many researchers are inclined to call late Soviet architecture built in Tashkent since then as ‘Seismic Modernism.’ However catchy this term may be, the truth is that not only it is not particularly seismic, but by and large, especially starting from 1980, it is most definitely not Modern, not in the sense of earlier pure International Style or Brutalist buildings. These creations are rather Post-Modern, reflecting global tendencies, namely historical and cultural references that infiltrated the country, which by then was no longer as hermetically sealed as it once was. Regardless of how these buildings are labeled, being large symbolic structures—predominantly freestanding, intrinsically public, spatially generous, solidly put together, and characteristically ornamented—they constitute a unique architectural system of urban markers with a strong common identity. Each of these buildings may not qualify as a true masterpiece; many were not superbly built and lacked refined details. The design origins of even the most daring and original of these buildings can often be traced to their Western prototypes. For example, one of the most persuasive examples, the Lenin Museum, which is featured on the city’s coat of arms, is designed in line with such predating international buildings as the American Embassy in New Delhi by Edward Durell Stone (1959).

Nevertheless, Tashkent must cherish its unique layer of late 20thcentury architecture, a cross between modern and traditional, international and local, Soviet and national. Most of all, it is the collection of these buildings and their strong common character that’s important to preserve and celebrate here. Such architectural heritage is rarely achieved in modern cities anywhere. In any case, the question we should explore is not whether to preserve these very special buildings but how.

Following the keynote lecture by Rem Koolhaas, who playfully demonstrated how to bring ideas of preservation into the design arsenal of contemporary architects around the world I asked him about the origin of his own inspiration to use preservation as a sort of design tool, which he masterfully applies to his projects, from the scale of a building to the scale of a city. His particular contribution is in the creative use of preservation by exploring various strategies for deciding what parts should be preserved, removed, remodeled, added, or even mixed and fused together with future additions. This is vital because bringing preservation ideas into practice has evolved into a design language that is now shared by many practicing architects globally. Koolhaas’s preservation projects such as Garage Museum for Contemporary Art in Moscow (2011-15) and Fondazione Prada in Milan (2008-18) serve as the seminal beacons for going forward.

The architect’s response to my question was: “I really love Roman architecture. I see it as the core of architecture. For me, Roman architecture is an emblem and a great paradigm of preservation because, to a large degree, it is left alone and remains almost untouched. Of course, there is maintenance, but there is a great deal of accumulation of decay, which I like. I was always interested in architecture which tends to remain and has a potential to remain. I always saw such architecture as a sort of my own ideal. In the course of the 1990s, I became aware of buildings being preserved for economic reasons. That’s how my interest grew in the ideas of preservation, particularly the entanglements between preservation and gentrification. Gradually, these issues became more interesting and more challenging to me.”

Now the challenge of dealing with the late Soviet buildings in Tashkent is how to connect them sensitively to our own time as well as the future, which is no longer about creating something entirely from scratch. Alternatively, the idea of preserving architecture that has the potential to remain is rather beautiful.

Vladimir Belogolovsky is the co-author of 'Soviet Modernism' (TATLIN, 2010) with the late Soviet architect Felix Novikov who coined the term, referring to Soviet architecture built between 1955 and 1985.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Nov 03, 2023

What do you think?