An ongoing project by Indian architecture practice wants to help people 'BreatheEasy'

by Mrinmayee BhootJun 10, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Oct 10, 2024

The evolution of a post-colonial identity for India has always been intrinsically tied to a search for an architectural idiom that reflects the ideals of an independent nation. If it were the British who sought to position themselves as the rightful rulers of the country through public architecture, a clean break with the colonialist model would also need to concern itself with how new developments in the country’s built environment would be construed. A post-colonial condition—or the transition of the newly independent population from the "not yet" to the civilised enough as the West was—would then manifest in architecture through the building of institutions; to suggest an almost overnight social transformation into a civilised, sovereign peoples. It’s vital to note that any genealogy of the search for an Indian architectural language must acknowledge the socioeconomic factors of the era and how these would come to affect the oeuvre of prominent Indian architects practising at the time.

The same thread, a concern with developing the nascent nation’s institutions while maintaining a distinctly Indian idiom of building also runs through the works of the late CP Kukreja, a New Delhi-based architect who established his eponymous firm in 1969, following an education in Melbourne and Canada. An architectural exhibition of the late architect’s legacy and the firm’s ongoing work in India under the tutelage of Dikshu C. Kukreja, Reimagining Architectural Transformations in Post-Independent India was recently displayed at the Nehru Centre, London from October 01 - 04, 2024. To trigger conversations around this search for post-coloniality which remains an ongoing debate for a still rapidly transforming country (expressed through its architectural transformations), an event to launch the exhibition was hosted by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), the High Commission of India and the CP Kukreja Foundation for Design Excellence on September 30, 2024. The event’s programme included a keynote address by Dr Valerie Vaughan-Dick MBE, Chief Executive of RIBA; and a dialogue titled ‘Empire to Expression – Transition from Colonial to Independent Architectural Styles’. The talk between Dikshu Kukreja, Director, CP Kukreja Foundation for Design Excellence and Managing Principal at CP Kukreja Architects; and Ar. Sumita Singha OBE, RIBA Trustee was moderated by Anmol Ahuja, Features Editor at STIR.

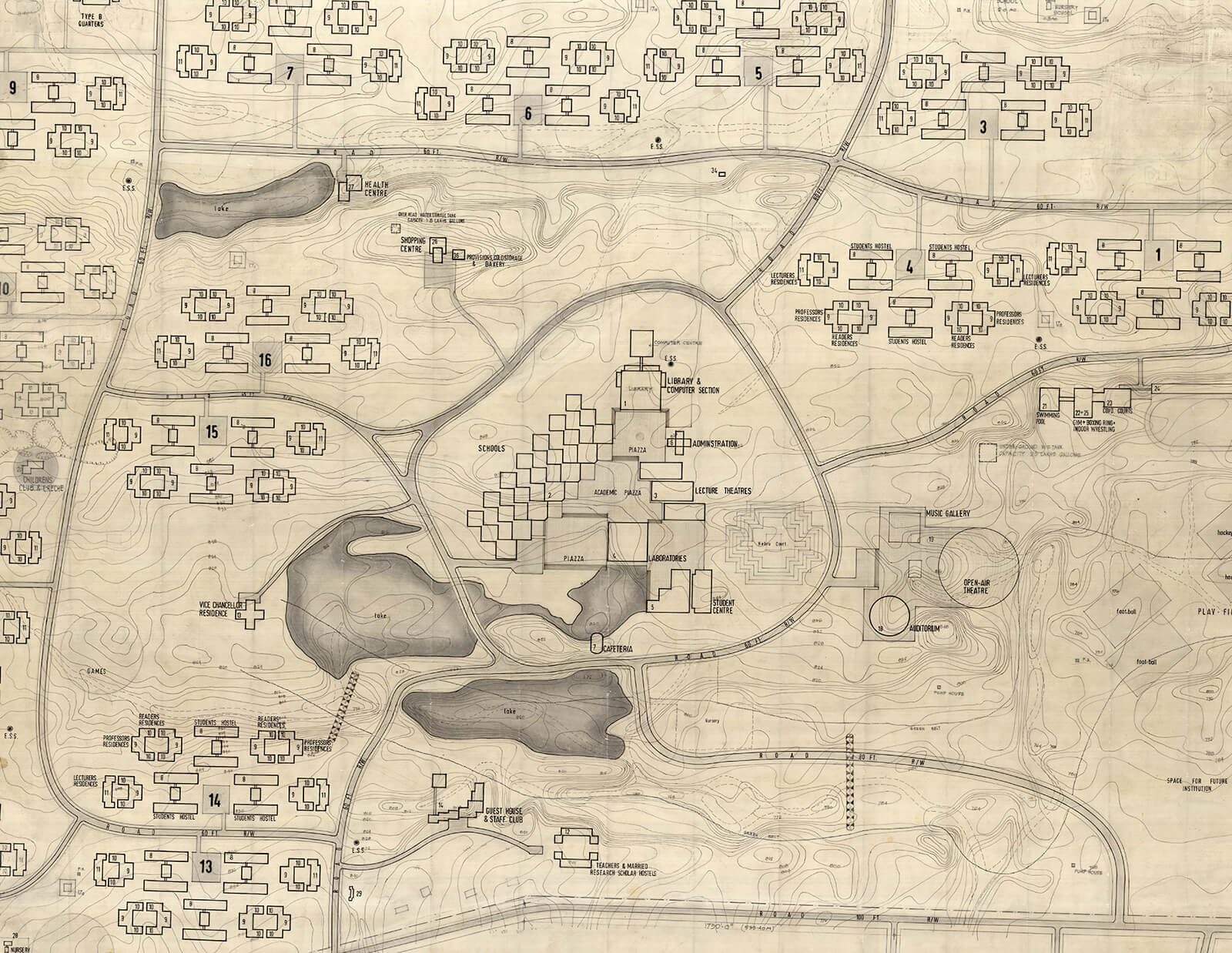

As the official release for the design event points out, the showcase offers insight into the “dynamic journey of Indian architecture post-independence, spotlighting key moments in the transformation of the nation’s built environment” over the past five decades. The showcase’s timeline begins in 1965, with the commencement of the planning for the Jawaharlal Nehru University, an exemplar of the kind of transformation envisioned by the then government for its people. Notably, the buildings on display, from the '70s to ongoing projects succinctly trace the evolving socio-political situation of the republic through institutional and commercial architectures. Reflecting upon this crucial theme of the exhibition through the works of the Indian firm, the dialogue between Kukreja and Singha dwelled on the challenges in this search for an Indian identity and the inherent need for such in the post-Independence era and later, in the age of post-liberalisation and globalisation. Pertinently, the dialogue also questioned the agency of architecture in determining how a public identifies itself and its relation to a nation.

The event on the 30th was also graced by Mr Vikram Doraiswami, High Commissioner of India to the UK and Mr Virender Sharma, Member of Parliament, United Kingdom. By turning away from a simplistic engagement with vernacular principles to reflect on the role of architecture in conversations on sustainability and a political scenario wherein India hopes to step outside its perception as a developing nation, the title of the exhibition is particularly interesting, a re-imagination of architectural evolution in the country. Through this, it pertinently asks: what other ways are there for us to think about the built environment? How might we define Indianness today? How might we recontextualise the postcolonial?

While the '60s and '70s were marked by the strong socialist leanings of Indira Gandhi, then Prime Minister, they were also defined by Indian architects (trained in the West) experimenting with pluralistic expressions of vernacular architecture, in a bid to explore what Indian could mean in design. The monumentality of architecture at this time represents these dual influences, largely a result of the socialist state’s agenda of societal transformation. As Indira Gandhi wrote in a letter to the JIIA in 1968, “In the past few decades, our architects have walked amongst international and indigenous idioms in search of an identity," yet only a few “lay claim to being genuine architecture”. Whether this genuine architecture could be achieved through the abstraction of Indigenous elements or the adaptation of Western models is a topic worth dwelling on.

Within the exhibition space, the curation outlines this question through select milestones in the architect’s practice. At the age of 32, the late CP Kukreja would win a national architectural competition for the design of Jawaharlal Nehru University. It would set the tone for the nature of works undertaken by his architecture firm in later years. The master plan for the institution, reflected not only the socialist ideals it was founded on but also displayed a particular concern with the local context and ecology, significant for the time. Further, the use of brick and low-density structures signalled this ongoing search for Indianness through the material and formal expressions.

The company’s pivotal role in institution-building in the country was further highlighted by other projects on display in the exhibition space. For instance, IIM Lucknow was conceived by the practice around 1984 and sought to emulate the architectural character of Lucknow with buildings set amidst landscaped gardens. Covered paths provided necessary interconnections between the blocks and common public spaces interjected between them. The Awadh influences on the design are evident in elements like false walls, double walls and networks of corridors that also function as climate-responsive techniques. The evolving language of educational architecture in the country and the various issues they aim to address are further showcased through case studies of Gautam Buddha University and Biswa Bangla Biswabidyalay (ongoing). It’s interesting to note how the incorporation of traditional techniques and materials begins with a concern for incorporating Indian idioms in design, evolving to a concern with addressing the climate crisis through indigenous knowledge systems.

Other projects on display include the Ambadeep Tower, designed in 1990. The structure is easily identifiable by its distinctive Art Deco facade design, seemingly inspired by Persian tile work. As the architects mentioned, Kukreja aimed to move away from stereotypical high-rise buildings through the colourful exterior, coupled with traditional elements such as courtyards and terraces in a modern idiom. The Statue of Oneness and the masterplan for Ayodhya currently being worked on by the firm attest to the aspirations and political ideologies of the country, towards exaggerated ‘state of the art’ development and hence, global recognition.

There is something to be said here about the scope of such architectural exhibitions that foreground expressions of Indian culture. Tracing back to Gandhi’s machinations with the Festival of India showcases in the '80s, these displays have often fostered cultural dialogue between countries and challenged any prejudices linked to the displayed works. Reflecting on the significance of the exhibition today, Kukreja commented, "This exhibition serves as a testament to the architectural evolution of India over the past 50 years. It challenges the limited perception of Indian architecture by offering a fresh narrative—one that showcases the country's rich and diverse built environment, rooted in modernism, sustainability and innovation."

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Oct 10, 2024

What do you think?